History

The following text on Magnum’s history is by Fred Ritchin, taken from the book Magnum Photos, published by Nathan in the Collection Photo Poche, 1997.

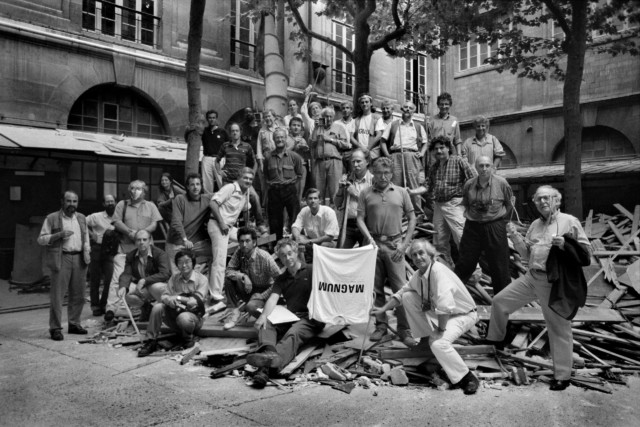

Two years after the apocalypse that was called the Second World War ended, Magnum Photos was founded. The world’s most prestigious photographic agency was formed by four photographers – Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, George Rodger and David “Chim” Seymour – who had been very much scarred by the conflict and were motivated both by a sense of relief that the world had somehow survived and the curiosity to see what was still there. They created Magnum in 1947 to reflect their independent natures as both people and photographers – the idiosyncratic mix of reporter and artist that continues to define Magnum, emphasizing not only what is seen but also the way one sees it.

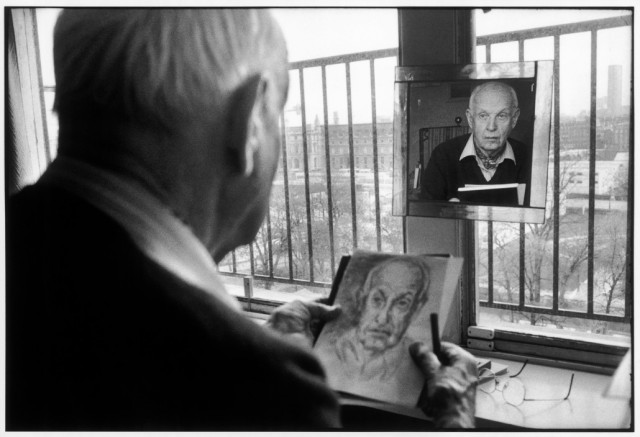

“Back in France, I was completely lost,” legendary photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson explained in an interview with Hervé Guibert in Le Monde. “At the time of the liberation, the world having been disconnected, people had a new curiosity. I had a little bit of money from my family, which allowed me to avoid working in a bank. I had been engaged in looking for the photo for itself, a little like one does with a poem. With Magnum was born the necessity for telling a story. Capa said to me: ‘Don’t keep the label of a surrealist photographer. Be a photojournalist. If not you will fall into mannerism. Keep surrealism in your little heart, my dear. Don’t fidget. Get moving!’ This advice enlarged my field of vision.”

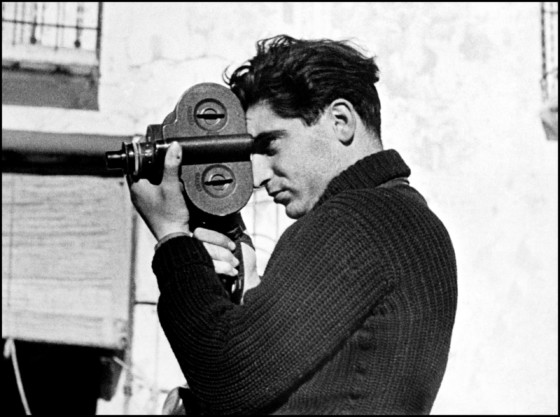

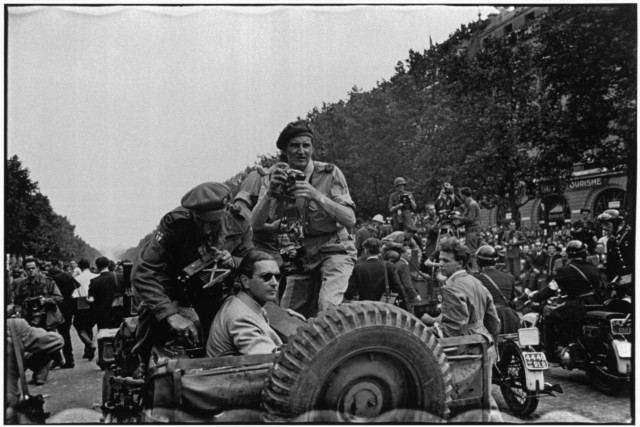

Englishman George Rodger, another of Magnum’s founding photographers, recalled how his colleague Robert Capa, the agency’s dynamic leader, envisioned the photographers’ role after World War II, which had itself been preceded by the invention of smaller, portable cameras and more light-sensitive film: “He recognized the unique quality of miniature cameras, so quick and so quiet to use, and also the unique qualities that we ourselves had acquired during several years of contact with all the emotional excesses that go hand in hand with war. He saw a future for us in this combination of mini cameras and maxi-minds.”

There had been both emotional and physical excesses. Rodger, noted for his pictures of the Blitz and the liberation of Bergen-Belsen, had had to walk “three hundred miles through the bamboo forest and what seemed like a thousand mountain ranges” to escape the Japanese in Burma. He would give up war photography forever after finding himself “getting the dead into nice photographic compositions” upon entering the concentration camp. Cartier-Bresson spent much of the war as a German prisoner and, after escaping on his third try, in the French Resistance. Polish-born David Seymour (known as “Chim”), who received a medal for his work in American intelligence, had lost his parents to the Nazis (his father was a publisher of Hebrew and Yiddish books). And Hungarian Capa, whose name was synonymous with war photography since the Spanish Civil War, made the blurred, visceral photographs of the D-Day invasion that became its symbols. Tragically, two of the four founders – Capa and Chim – would die within a decade covering other wars.

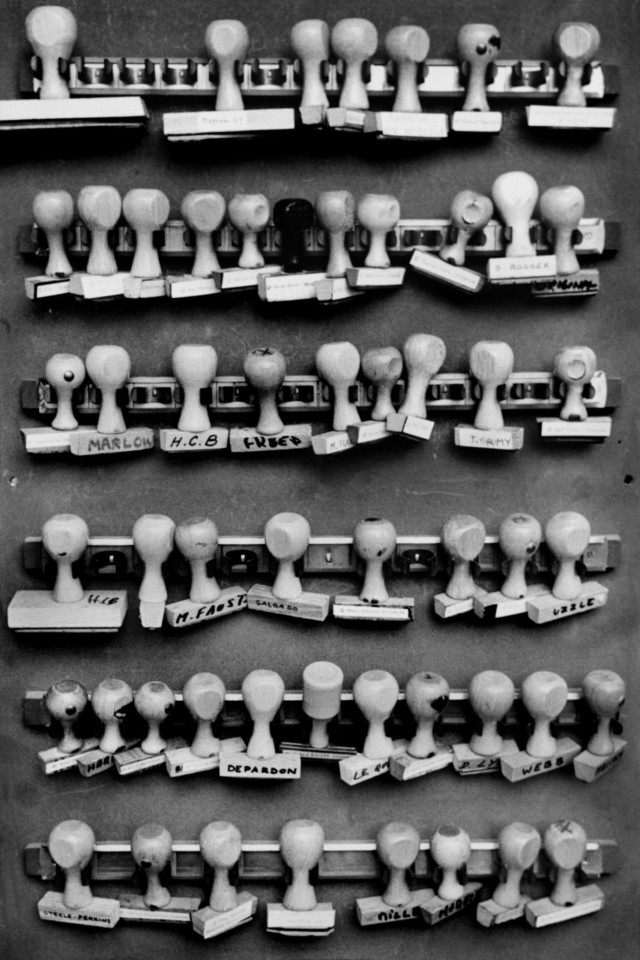

These four formed Magnum to allow them and the fine photographers who would follow the ability to work outside the formulas of magazine journalism. The agency, initially based in Paris and New York and more recently adding offices in London and Tokyo, departed from conventional practice in two fairly radical ways. It was founded as a co-operative in which the staff, including co-founders Maria Eisner and Rita Vandivert, would support rather than direct the photographers. Copyright would be held by the authors of the imagery, not by the magazines that published the work. This meant that a photographer could decide to cover a famine somewhere, publish the pictures in “Life” magazine, and the agency could then sell the photographs to magazines in other countries, such as Paris Match and Picture Post, giving the photographers the means to work on projects that particularly inspired them even without an assignment.

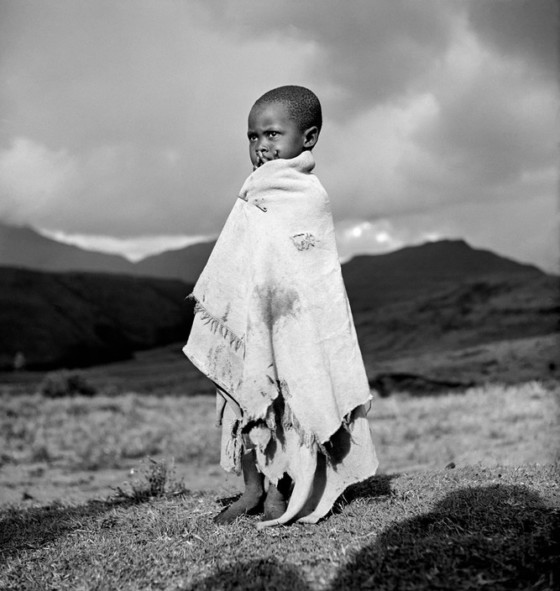

In those days a photographer had a significant advantage: large areas of the world had hardly ever seen a photographer. They could choose to go almost anywhere they wanted, as Rodger pointed out, because in the early days one could “take pictures of just about anything and magazines were clamoring for it; the mistake was in thinking that it would continue.” Still, four decades later, at the age of 75, Rodger was averaging one sale a month of the photographs he had taken in Africa in the late 1940s during a self-initiated post-war trip that he had undertaken “to get away where the world was clean.”

Magnum’s first move was to divide the world, rather loosely, into flexible areas of coverage, with Chim in Europe, Cartier-Bresson in India and the Far East, Rodger in Africa, and Capa at large and replacing Bill Vandivert (an American who had helped found Magnum but soon dropped out) in the USA. They had some early scoops, such as Robert Capa’s first uncensored look behind the Iron Curtain at the Soviet Union with the writer John Steinbeck, [originally published in “Ladies Home Journal” (for which Capa, according to John Morris, the Journal’s picture editor and later Magnum’s executive editor, was paid $20,000 to Steinbeck’s $3,000)], and Cartier-Bresson’s landmark coverage of India at the time of Gandhi’s assassination.

It was important for Magnum’s photographers to have this flexibility to choose many of their own stories and to work for long periods of time on them. None of them wanted to suffer the dictates of a single publication and its editorial staff. They believed that photographers had to have a point of view in their imagery that transcended any formulaic recording of contemporary events.

"There's no standard way of approaching a story. We have to evoke a situation, a truth. This is the poetry of life's reality"

- Henri Cartier-Bresson

“We often photograph events that are called ‘news’, ” Cartier-Bresson told Byron Dobell of “Popular Photography” magazine in 1957, “but some tell the news step by step in detail as if making an accountant’s statement. Such news and magazine photographers, unfortunately, approach an event in a most pedestrian way. It’s like reading the details of the Battle of Waterloo by some historian: so many guns were there, so many men were wounded – you read the account as if it were an itemization. But on the other hand, if you read Stendhal’s Charterhouse of Parma, you’re inside the battle and you live the small, significant details… Life isn’t made of stories that you cut into slices like an apple pie.”

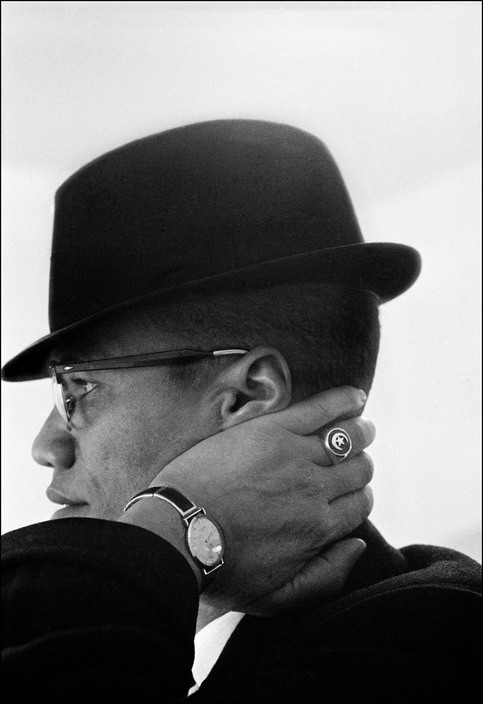

Within five years of its founding, Magnum had also added to its roster talented young photographers such as Eve Arnold, Burt Glinn, Erich Hartmann, Erich Lessing, Marc Riboud, Dennis Stock and Kryn Taconis. Riboud soon followed Cartier-Bresson with his own pioneering work in China, the first of many trips in what has become a lifelong interest. Arnold took a memorable series of pictures of the Black Muslims and of Marilyn Monroe. Taconis covered the Algerian war for independence. Soon others such as Rene Burri, Cornell Capa (Robert’s younger brother), Elliott Erwitt and Inge Morath would join. The agency was growing. But there was a feeling that it was heading in some wrong directions. In a memorable 1962 memo addressed to “All Photographers” Cartier-Bresson, attempted to remind the photographers of their place in the world:

“I wish to remind everyone that Magnum was created to allow us, and in fact to oblige us, to bring testimony on our world and contemporaries according to our own abilities and interpretations. I won’t go into details here of who, what, when, why and where, but I feel a hard touch of sclerosis descending upon us. It might be from the conditioning of the milieu in which we live but this is no excuse. When events of significance are taking place, when it doesn’t involve a great deal of money and when one is nearby, one must stay photographically in contact with the realities taking place in front of our lenses and not hesitate to sacrifice material comfort and security. This return to our sources would keep our heads and our lenses above the artificial life, which so often surrounds us. I am shocked to see to what extent so many of us are conditioned – almost exclusively by the desires of the clients…”

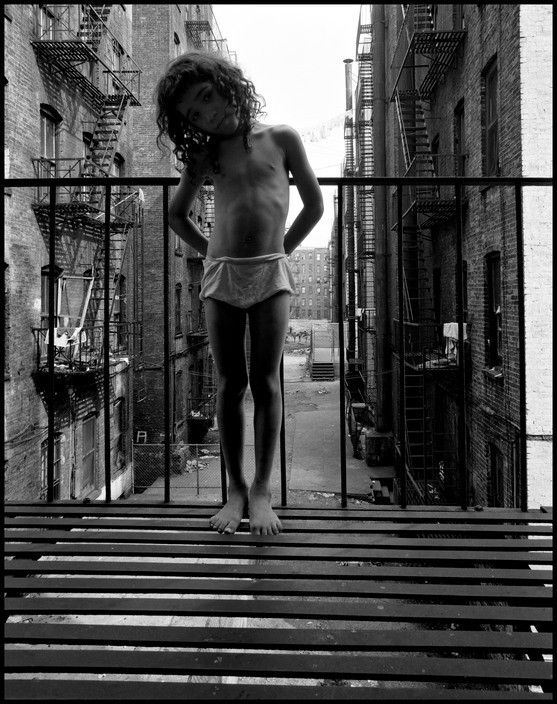

Many Magnum photographers have succeeded brilliantly at transcending “the artificial life” and exploring life’s realities subsequent to Cartier-Bresson’s memo, as well as before. Bruce Davidson’s “East 100th Street” is an extraordinary formal meditation on the lives of people living on an impoverished New York City block, and Philip Jones Griffiths’s 1971 book, “Vietnam Inc.”, is a brilliantly sardonic, even ferocious, look at the policy of the United States in Vietnam.

So while photographers were having success publishing photographs in magazines, such as Susan Meiselas’s photographs of the Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua, or Gilles Peress’s photographs of Northern Ireland and the upheaval in Iran, many Magnum photographers were increasingly turning to books and exhibitions to express themselves. Meiselas’s “Nicaragua”, Peress’s “Telex: Iran”, Salgado’s “L’Homme en Detresse” were attempts to give a more sophisticated and visionary explication of world events. As Magnum’s photographers began to experiment with text and with book and exhibition design, their photographic language began to evolve as well. For many the direct testimony that Magnum’s founders believed in no longer was sufficient in a media-saturated world where photography was increasingly used to illustrate the points of view of editors and art directors, of politicians and movie stars, at the expense of the photographers.

Raymond Depardon worked on a pioneering effort with the French daily newspaper Liberation to report on New York City by providing a single picture every day for the newspaper’s foreign-affairs page with a diary-like text that described the people he met, what he was reading, his very personal feelings; Peress’s book, “Telex: Iran”, included the telexes he received from Magnum’s staff as a way of highlighting his quasi-mercenary, foreign role along with photographs that raised questions more than providing authoritative responses as to what was happening.

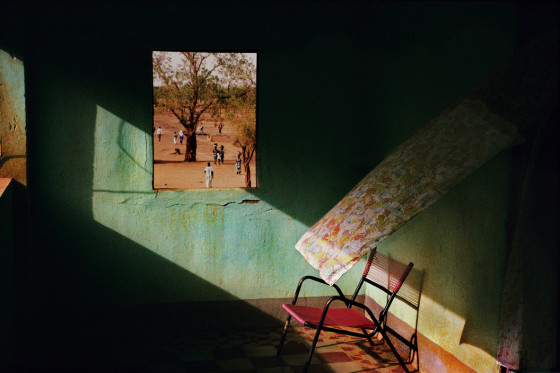

Eugene Richards’s books combined the intimate and the public in raw exposes of the suffering of the impoverished, the sick, the addicted; Harry Gruyaert and Alex Webb’s work in Morocco and the Caribbean, respectively, revelled more in the self-conscious exoticism of the observer rather than trying to reveal the societies’ underpinnings.

For today’s younger generation of photographers there is much less of a sense that simply reporting on an injustice is sufficient, and there is a much more complex awareness as to what is or is not possible to explain. Right now, “If your pictures aren’t good enough you may be too close rather than not close enough,” as Capa put it long ago. In today’s “information age”, if the reader can be enjoined to enter the quest for meaning, then one has succeeded. With all of Magnum’s prickly personalities, with all the difficulties inherent in attempting to see differently, it is a wonder for many that the agency has managed to survive almost sixty years. Very few cooperatives are noted for their longevity. Magnum, in its idiosyncrasy, its inability to stand still, has been a remarkable exception.