Making the Image: Miles Davis

Guy Le Querrec reflects on his magnetizing documentation of the Miles Davis quintet and what it was like capturing the intimacy of live music through images

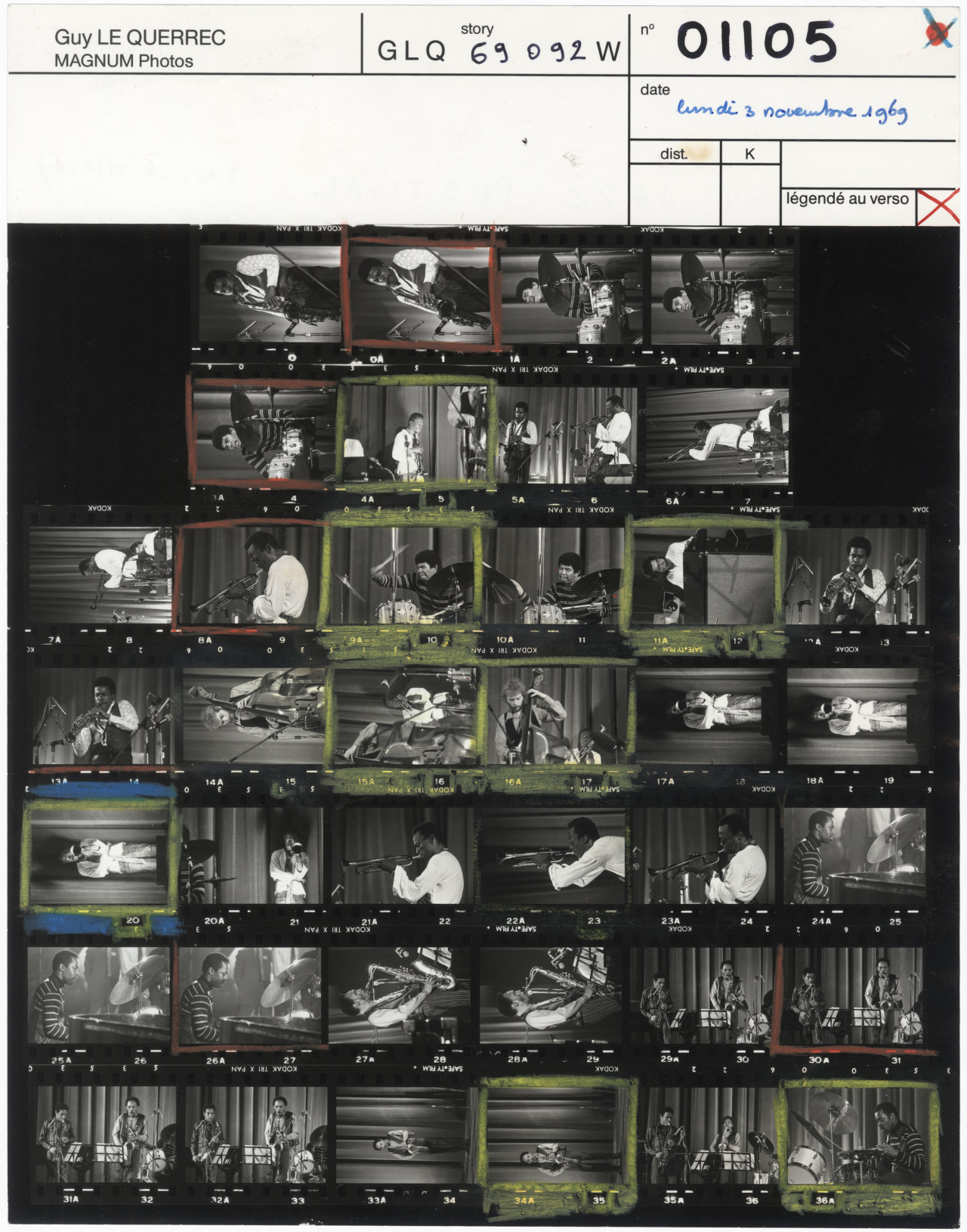

Contact sheets: direct prints of sequences of negatives were, in the pre-digital era, key for photographers to be able to see what they had captured on their rolls of film. They formed a central part of editing and indexing practices, and in themselves became revealing of photographers’ approaches: the subtle refinements of the frame, lighting and subject from photograph to photograph, tracing the image-maker’s progress toward the final composition that they ultimately saw as their best. There is a voyeuristic aspect to looking at a contact sheet also: one can retrace the photographer’s movements through time and space, tracking their eye’s smallest twitches from left to right as their attention is drawn. It is as if one were inside their head, offered a privileged view through their very eyes from the front row of their brain.

As Kristen Lubben wrote in her introduction to the book, Magnum Contact Sheets, first published in 2011 by Thames and Hudson:

“Unique to each photographer’s approach, the contact is a record of how an image was constructed. Was it a set-up, or a serendipitous encounter? Did the photographer notice a scene with potential and diligently work it through to arrive at a successful image, or was the fabled ‘decisive moment’ at play? The contact sheet, now rendered obsolete by digital photography, embodies much of the appeal of photography itself: the sense of time unfolding, a durable trace of movement through space, an apparent authentication of photography’s claims to transparent representation of reality.”

Here we look at the making of Guy Le Querrec’s capture of Miles Davis quintet during the Paris Jaz festival in 1969. Le Querrec’s contact sheets show us his unique ability to anticipate and prepare for each move of the musicians allowing him to take electrifying images of the jazz concert.

Paris, France, November 1969

“After a concert by Duke Ellington and his orchestra on 1 November 1969, the organizers of the 6th Paris Jazz Festival had scheduled a double concert in the Salle Pleyel for 3 November at 7.30pm and again at 10.30pm. Miles Davis’s quintet, with Wayne Shorter on sax, Chick Corea on keyboards, Dave Holland on double bass and Jack DeJohnette on drums, was to appear on stage before Cecil Taylor’s quartet. I had decided to photograph all the concerts. By now I was working as head of the photo department at the Paris based weekly magazine Jeune Afrique, so I also did regular reports in Africa, but I continued to photograph jazz as often as I could.

This was the second time that Miles Davis had entered my viewfinder, the first time being at the 1st Paris Jazz Festival in October 1964. I was still an amateur then. In those days, stages were brighter and the technical conditions were easier than they are today. Back then I took fewer photos, too. This was doubtless due to the need to be economical, but it was also because, being able to leave fewer things to chance, I had to concentrate harder in a given situation. This was certainly the case during the 10.30pm concert.

Although live music is always a visually dramatic art form, this concert was particularly noteworthy. As happened from time to time throughout the gig, Miles wandered away from the centre of the stage and the microphones to let his musicians take turns improvising. I had a premonition of the move he was going to make. Anticipating it, I was in just the right place when he stopped for an instant in a beam of light that was emanating from the floor, illuminating him in my low angle shot and throwing a shadow on the curtain at the back. Miles passed without transition from the full uniform lights of the show into a single sophisticated, sculptural light. It accentuated his strange, enigmatic, fascinating beauty and emphasized the depth of his gaze – the same qualities found in his music.”