Magnum On Set: The Alamo

Wayne Miller and Dennis Stock’s photographs from John Wayne’s 1960 directorial debut, a personal work that revealed the actor's insecurities around his status as a war hero who had never served

Magnum Photographers

Magnum photographers have, over more than seven decades, captured pivotal moments in popular culture as much as historic events and societal sea changes. Working behind the scenes on sets of many classic films, they have captured not only iconic stars at various stages of their careers, but also documented the changing nature of cinema and film production. Sets, equipment, and special effects that once seemed futuristic are, with the passing of time rendered disarmingly romantic.

The John Wayne-directed 1960 film The Alamo was a tale of American tragedy, machismo, and sometimes grandiose heroism. Though historically inaccurate in many respects, the film holds particular significance as a chronicle of American patriotism and for the insight it offered into its director Wayne. Here we explore Dennis Stock and Wayne Miller’s photographs, made on the set of the film.

See other stories in the Magnum On Set series, here.

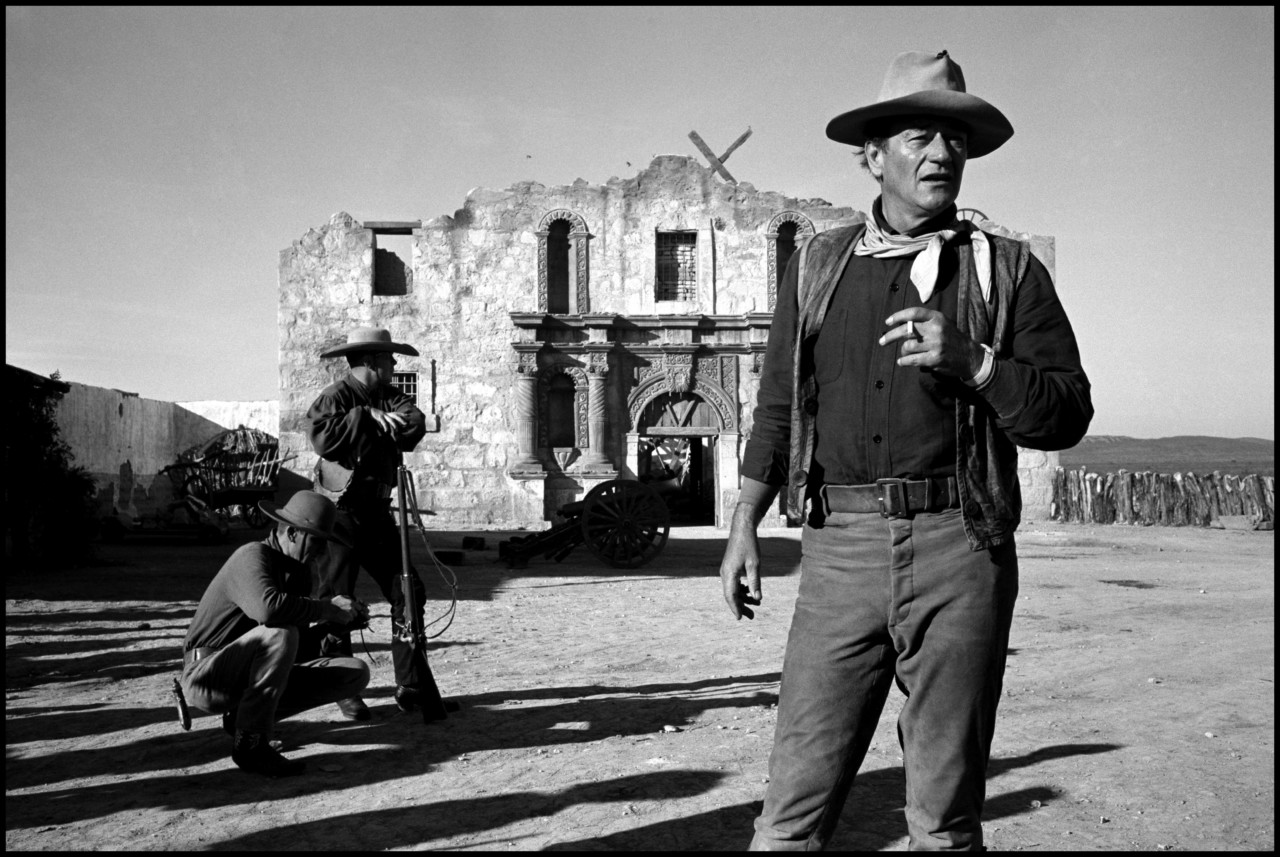

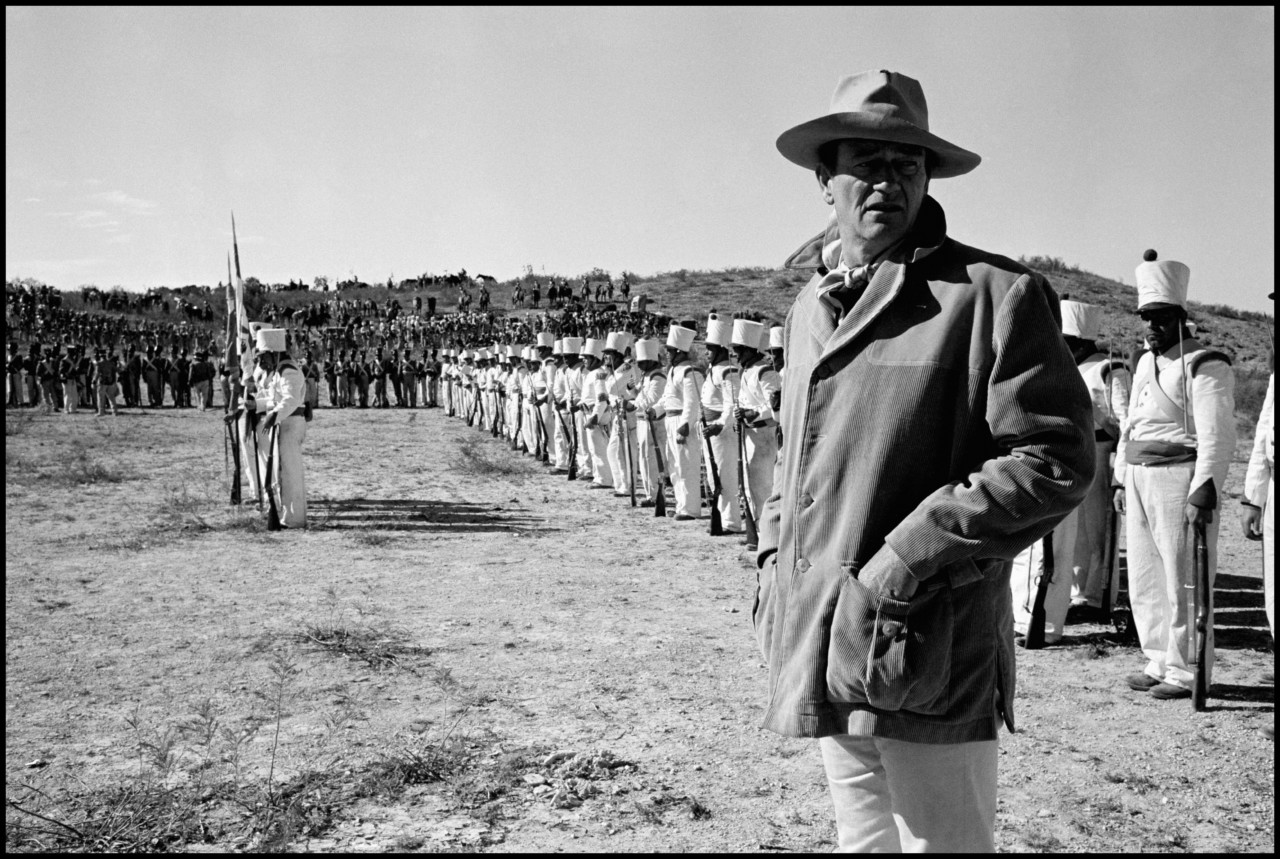

In Dennis Stock’s black and white photograph of the Alamo fortress, we see Mexican soldiers in battle tumbling to the desert ground from rearing horses; the dust they stir up shrouds a crumbling fort; on top of this the silhouettes of men in cowboy hats — Texan defenders —aim their weapons at their attackers. This scene was not captured during the 1836 Battle of the Alamo, but on the set of the 1960 movie retelling of the event, directed by John Wayne — who also starred — and shot in a replica fortress in Bracketville, Texas.

Wayne’s film told the fateful story, already familiar to many Americans, of the famous Battle of the Alamo, which occurred during the Texas Revolution of 1895-1896. An American military garrison of some 100 to 200 fighters defending the Alamo came up against approximately 1,800 Mexican troops, led by Mexican independence leader General Santa Anna. Wayne starred in the film as the seasoned hero Davy Crockett who leads a band of adventurers in supporting the defending Texans and dies honourably alongside them.

Wayne’s film was derided for its historical inaccuracy; it exaggerated by many times the degree to which the Texans were outnumbered and ornamented the circumstances of the deaths of the battle’s heroes — even the film’s historical advisors, displeased by the adaptation, demanded their names be removed from the credits. Critics had tepid reactions despite the film’s ambition in its dramatic retelling of events. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times wrote, “Mr. Wayne has unfortunately let his desire to make a ‘big’ picture burden him with dialogue.” The film’s at times long-winded monologues meditated on freedom in America and religion amongst other subjects— Wayne was an avid anti-communist, and a supporter of right-wing groups including the John Birch Society. The script’s tendency to pontificate on these topics, coupled with the film’s protracted running time, has meant that it is sometimes seen as a pet project that revealed more about its maker than it did about the events it claimed to portray.

Wayne, who went on to direct a further two movies over the course of his career, made his name as a leading actor in blockbuster Westerns. The actor lived professionally and personally under a larger-than-life image that exemplified Americanness and masculinity. Born Marion Robert Morrison, he had never been particularly fond of his real first name, preferring “Duke”, the nickname given to him as a schoolboy. It was film executives who had spied his potential stardom whilst he was working as a stagehand in 1930, and who had invented his screen name John Wayne. Adored by American audiences during the postwar decades, Wayne consistently drew money to box offices, making lists of top ten ticket-selling actors annually for 25 years. So popular was the actor, and so profoundly did he embody American values, that heads of states – notably Emperor Hirohito of Japan and President Khrushchev of Russia – both made requests to meet Wayne on diplomatic visits to the country.

The Alamo was not a huge commercial success upon its release – it made its $12 million budget back only after Wayne sold the film rights back to the studio, United Artists. A 2004 remake starring Billy Bob Thornton fared worse: costing $107 million and only earning $26million in cinemas, it’s often ranked amongst the worst box office bombs in history.

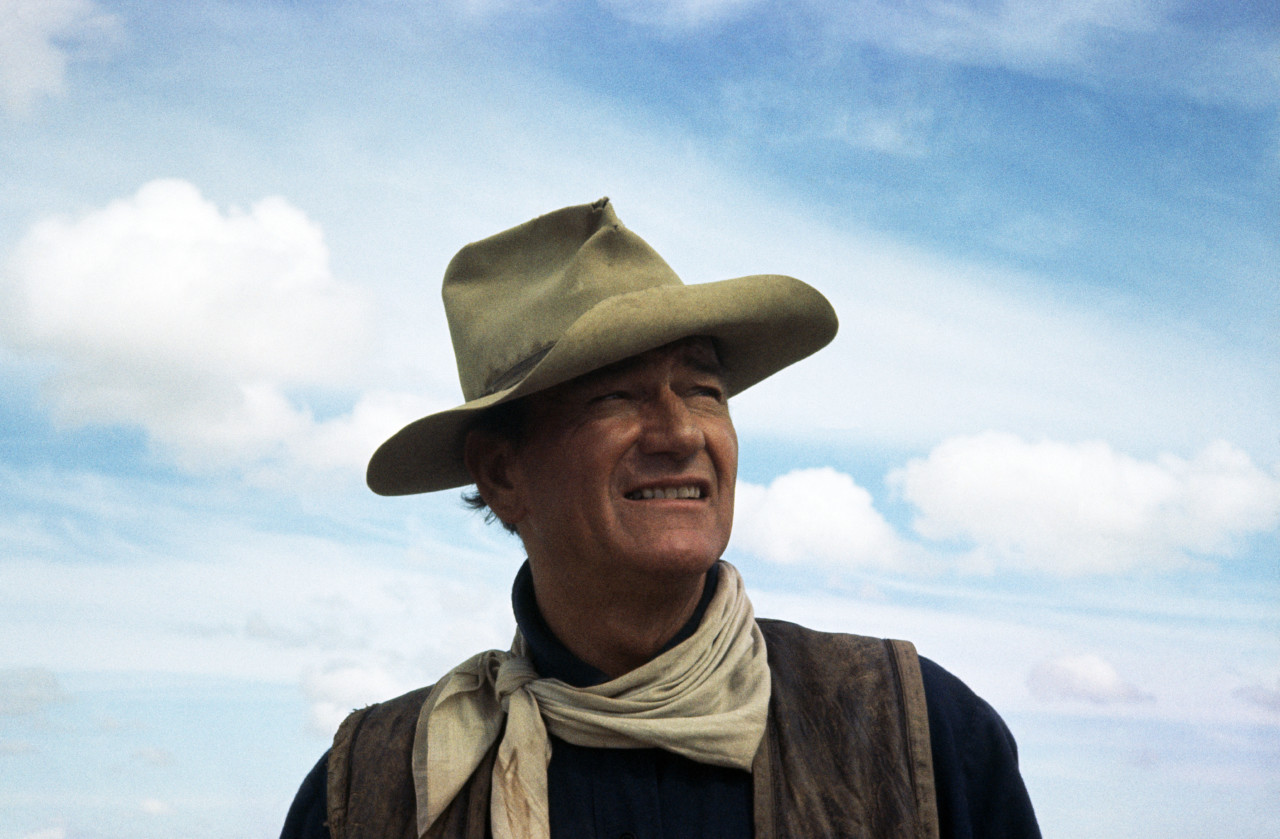

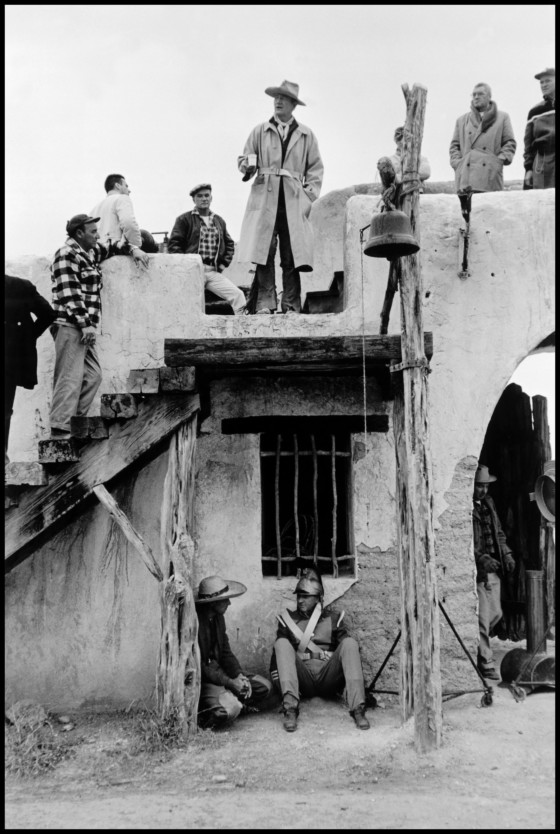

Dennis Stock documented culture in America over many decades, notably capturing the free-wheeling spirit of 1960s, countercultural California, and shot photographs behind the scenes of many of Hollywood’s biggest films — Planet of the Apes, Rebel Without a Cause – staring James Dean, and George Lucas’ early work American Graffiti, were just a few of many. In Stock’s photographs, Wayne as the creative authority flexes his directorial power. He appears unaffected in shots motioning to command cast and crew, his cigarette in hand. Stock shot his portraits from a lower angle and Wayne’s larger-than-life image seems to loom within the frame even more than usual.

"Wayne’s larger-than-life image seems to loom within the frame even more than usual"

-

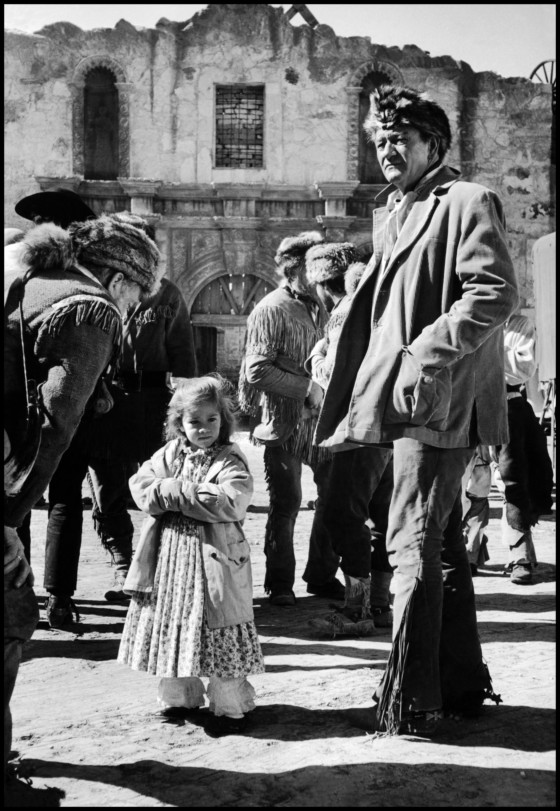

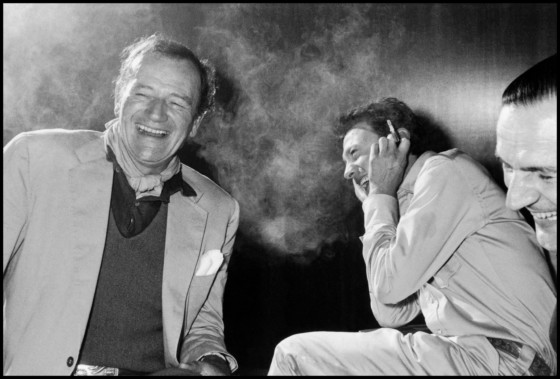

Initially gaining recognition for his humanist photography documenting universal conditions of life across cultures, Magnum photographer and former president of the agency Wayne Miller’s work famously touched on everyday life as well as racial dynamics in the American military. In Miller’s photographs, the star is captured during more relaxed moments, sharing a joke with his co-star Laurence Harvey, who played William Barrett Travis, and, in another image, being attended to by an on-set medic.

The intensely patriotic rhetoric of the film is said to have had roots in Wayne’s guilt around military service. Despite his career-long propensity for depicting marshal heroism, Wayne suffered from anxieties over having never served in the US military despite pressures from his regular collaborator, director John Ford, who had been head of the state’s wartime photographic unit and a commander in the Naval Reserve. Biographers Randy Roberts and James Stuart Olsen said of the actor: “On the screen Wayne was the quintessential man of action, one who took matters into his own powerful hands and fought for what he believed in. Never before or after would the chasm between what he projected on the screen and his personal actions be so great.”

Wayne’s age at the time of the World War II draft, and his family’s background, meant he was exempted from conscription. He applied to serve regardless, but repeatedly deferred, saying in his letters to Ford that he would enlist after “he finished just one or two pictures”. Wayne was a fervent supporter of the military. Decorated by the government multiple times for his services to the country via his cinema work, his recognitions included the Congressional Gold Medal, Presidential Medal of Freedom, and the Naval Heritage Award. Roberts and Olsen said Wayne had “become a war hero without ever serving”, a difficult position for such an ardent patriot. Wayne’s insecurities around this are touched upon by his third wife Pilar Wayne who remembers in her biography of the actor published after his death that “he would become a ‘superpatriot’ for the rest of his life trying to atone for staying home.”