Photography, Trump, the Manipulation of Public Sentiment, and the Phantasmagoria of Politics

Aaron Schuman in conversation with David Levi Strauss on his book, Co-Illusion, which features work by both Susan Meiselas and Peter van Agtmael

Magnum Photographers

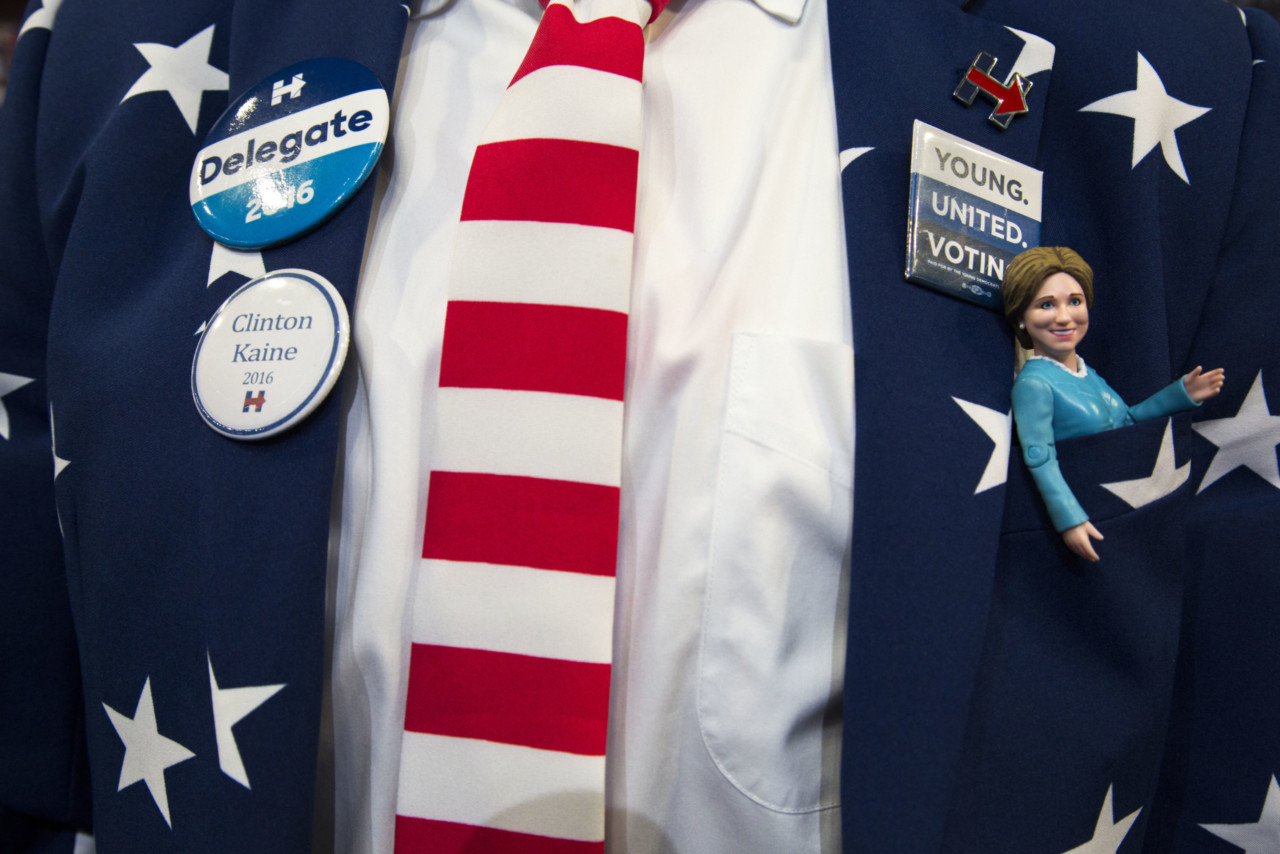

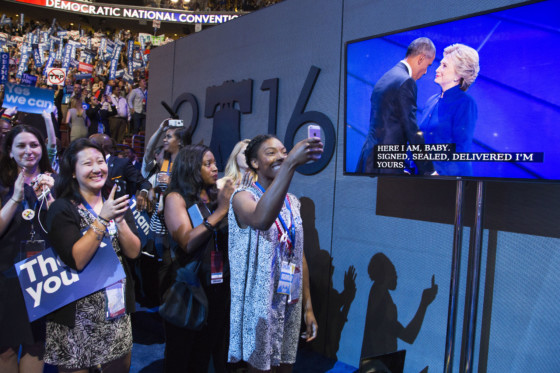

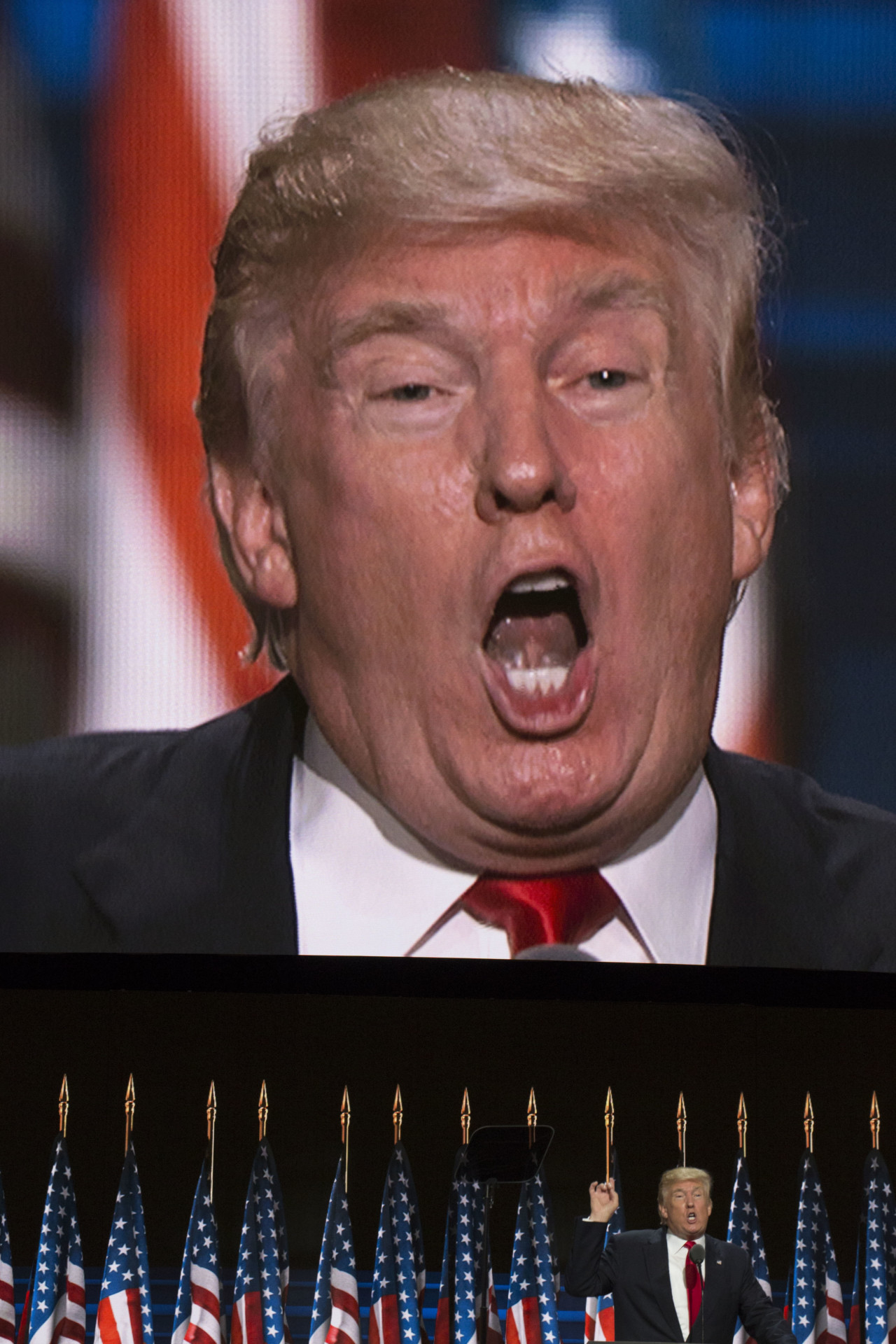

David Levi Strauss’ book, Co-Illusion: Dispatches from the End of Communication, published by The MIT Press in March 2020, examines ‘iconopolitics’, the wavering integrity of images, and the manipulation of mass communication via ‘dispatches from the epicentre of [America’s] constitutional earthquake’. Along the trail of America’s recent political rampages Strauss crossed paths with Magnum photographers Susan Meiselas and Peter van Agtmael, also documenting Republican and Democratic Conventions and the state of contemporary American politics. Their images from the front lines of media manipulation are woven throughout the book’s texts. Below, artist, writer and curator, Aaron Schuman discusses the book with Strauss.

Strauss recently gave a reading of an extract from Co-Illusion: Dispatches from the End of Communication, at Houston’s Fotofest. Watch the reading and see the author in conversation with Roberto Tejada here.

Aaron Schuman: To start, how did this project begin?

David Levi Strauss: As soon as I knew that Donald Trump was going to be the Republican nominee, I felt like I had to be there, and see the 2016 political conventions for myself. I had already been working with Jon Winet, an artist who has a longstanding practice of going to political conventions, and who often collaborates with writers within his work. Jon had figured out a way to get press credentials for the 2016 Republican and Democratic National Conventions – in fact he’s been doing this for forty years or so – and somehow he secured credentials for another photographer to accompany him, and invited me along. So throughout the project I had a photographer’s credentials, which in many ways turned out to be better than having a writer’s credentials because it gave me much more access. I’m not a professional photographer – and of course all of the photographers that were working at the conventions knew this right away – but I impersonated a photographer while I was there, and then wrote dispatches every night. Then, when the unthinkable happened, I started to write in a very different way; a kind of ventriloquism in which I adopted the voices of the regime, and the voices of complicity. That’s how the book started and evolved, but it took a long time.

Very early on in the book – in fact, in “Dispatch 3”, written during the Republican National Convention in July of 2016 – you write, “For eleven hours today, I talked with, observed, photographed, and commiserated with hundreds of Trump supporters.” What were you photographing – and were you photographing for yourself and this specific project, or was making images simply part of your roleplay?

Mostly the latter, although in the book there are a couple of my own photographs. In the late-1970s I studied with Nathan Lyons at Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester, New York, and with Jeff Weiss at Goddard College – so I do know how to make a photograph, and some of the pictures that I made at the conventions were used within the work that I was doing with Jon. But for the most part I was there as a writer pretending to be a photographer. That said, as you well know, one of the best ways to get to know something is to photograph it – you find out about it in a very different way, and that helped me a lot in terms of my writing as well.

What did you see that you might not have noticed if you hadn’t had a camera in hand?

As soon as I stepped onto the floor of the Republican National Convention back in 2004, I realized that I’d walked into a machine for making images; that’s what these conventions are, and have been for a long time. They’re entirely designed to be filmed and photographed – to be “imaged”. And if you have the right credentials you could watch certain parts of the apparatus work from behind the scenes. As I said, I’m not a journalist or a photojournalist, so it was an ecosystem that I wasn’t familiar with, and it was all entirely new and utterly fascinating to me.

What kinds of images were being contrived by this “machine” for the professional photographers who surrounded you in this ecosystem?

Actually, one of the most surprising things for an outsider like me was that it all seemed remarkably open and freeform. When I say that it’s a “machine for making images”, I don’t necessarily mean that the images are contrived; everything is available. For example, the Magnum photographer, Susan Meiselas – whom I’ve known for many years, and ran into at both conventions a number of times – was working on various projects, and I think that the photographs she made at them specifically reflect what she was looking at, what drew her eye, and what she was concentrating on, rather than being generic or contrived by others in any way.

In its preface, you state that the photographs included in Co-Illusion – mostly made by Susan Meiselas and Peter van Agtmael – serve as a “visual counterpart” to your writing. Were the three of you working totally independently at the time of the conventions, rather than collaboratively from the start of the project?

Yes. At a certain point the publisher suggested that Susan get involved in the book, and then when Susan came in she brought Peter, whose work I’d been a fan of for a long time. But really, both Susan and Peter just gave me the files of everything they’d shot during the election, and then I chose the particular images that I felt worked for the book, and sequenced them to be in dialogue with the writing; I think that a lot of the juxtapositions worked out remarkably well.

You already know all about this – as seen in your recent book, SLANT – but the thing I was trying to avoid was illustration, even though that’s what words and images want to do. The words want to explain the images, and the images want to illustrate the words. But if you can break that tendency, all kinds of interesting things happen – “slant rhymes” and so on.

The other important thing to note is that in the book we converted all of the photographs – by Susan, Peter and myself – from color into black-and-white, which was a huge move. I think that in a printed book, having the images in black-and-white puts them in the same register as the text, so in some ways there’s more possibility for integration than there would be with color photographs. Of course, there are all kinds of things that are possible with color images as well, but in this case I was struck by how well it worked once they became black-and-white images. It really changed things – the relationship between the words and images, and much more. A lot of photographers would have really balked at this, but both Susan and Peter were both fine with it, and were fantastic about the whole thing from beginning to end.

When speaking with students – or younger people in general – I’m often struck by the fact that they often see color photographs as being more “realistic” or “trustworthy” than black-and-white images. In the past, black-and-white photography was regarded as a form of realism, whereas color photography was seen as more fantastical, corporate or commercial. That seems to have been inverted within the eyes of recent generations.

It has – which makes me think about the writer and philosopher Vilém Flusser, who wrote, “Grey is the color of theory”, and argued that black-and-white images are conceptual. I mean, my God – when Susan’s book Nicaragua, June 1978 – July 1979 came out in the early 1980s, she was attacked all over the place for using color film – how dare she use color in a war zone! It seems ludicrous now, but it was a big deal at the time.

When these images are transformed into black-and-white, in a sense they become a bit more stark, stripped back, or streamlined in some way; they’re less colourful, less dazzling, and therefore perhaps more direct, accessible and telling.

I think so, and especially in this context. Susan and Peter were photographing deep inside this machine, which as you say uses color as an important part of its spectacle, and is now entirely built for color imagery. Seeing their work in black-and-white dampens that down a bit and can cut through it. Simple things – faces, gestures, spatial relationships, and so on – become more revealed, and more revealing.

The other thing that is very prevalent within the photographs you chose for this book is the presence of text within the images themselves – teleprompters, hand-held signs, t-shirts covered in slogans, TVs with captions or news tickers crawling across them, a giant screen that read “TRUMP” in the boldest of letters, and so on. In your eyes, what happens when text appears in an image, rather than beside it?

Well it’s a complicated thing. In this context everything is geared towards and intended to be photographed or seen on a screen – to be “screenal” – but it’s also very message oriented. The message is the most important thing, and that often means that text is placed within the image itself. At the end of the conventions they do all kinds of things that are orchestrated from the floor, where the crowd itself becomes textual; that’s part of the phantasmagoria.

I still think that, for the longest time, people like me who write about photography and its effects haven’t accounted as much as we should have for the fact that photographic images almost never appear alone – they’re always accompanied by text, and often feature text within themselves, which totally changes their effect and our relationship to them. I’ve tried to deal with this a little bit, but not enough people are exploring this, and there’s more work to be done in this regard.

Specifically within Co-Illusion, I wondered if it also had something to do with the fact that both Trump’s campaign and supporters are mistrustful of the media, and in some ways by insisting that text be included in the images, it was their attempt to direct, subvert and fully control the message of the imagery itself.

Well, that strategy came long before Trump, and is something he’s inherited. But being at the Republican convention four years ago – and I had been to many conventions before that – was certainly a singular experience. Trump is an exalted master of mass manipulation of public sentiment, and is able to both use and change the tools at hand. Furthermore, he can also claim to be the first real social-media President, and his use of social media is very powerful. Trump even claims that Mark Zuckerberg told him that he was “number one on Facebook”, and has said himself that without social-media he wouldn’t even be President.

In the book, you make a distinction between the notion of Plato’s Cave, and what you refer to as the “Reality Tunnel”, or “the way each person constructs a view of the world according to her or his experiences and beliefs.” Could you expand on the comparison between those two metaphors?

I think that the term “reality tunnel” was first coined by Tim Leary in the early 1970s, and in some strange way it seems that things have circled back to then; for me today has a lot of similarities to that period. Growing up in Kansas, I tuned into electoral politics early on; when I was nineteen years old I worked for George McGovern’s presidential campaign in 1972 – and we lost everything, McGovern even lost in his home state. The way that people were talking about the diminishment of our hold on the real back then – or what we might now call reality-hacking – isn’t that dissimilar to today.

What do you think that social media has added to the notion of the “reality tunnel”? Is today’s digitized version of this tunnel simply a heightened, steroidal version of Leary’s idea, or is it something new or different?

Both, in different ways. To be honest, I’m still trying to sort this out. In the book, there’s a section where I talk in the voice of Mark Zuckerberg. I’ve followed him very closely for a long time, and I think that it’s now pretty clear what side he’s on; he and Trump have been great for each other, and Trump has rewarded him handsomely. And with that in mind, it’s obvious that there’s definitely something wrong with this idea that social media are just transparent platforms rather than publishers – I can’t believe that this idea gained any currency when it did, or that people still defend this position, but now many people cling to it. If this is the case, I don’t think that democracy is going to last – social media simply rewards the loudest, most vociferous voices, and really doesn’t work for any kind of critical thinking at all.

Nearly thirty years ago, in an essay entitled “Photography and Belief” (1991), you wrote, “The aura of believability surrounding photographs is not all that vulnerable to new electronic imaging technologies in themselves. But belief itself is vulnerable to […] massive propaganda assault[s] and the general degradation of information.” Isn’t that precisely what’s happening now?

Definitely. I’ve finally just written a little book that I’ve been meaning to write for a long time on photography and belief, which will be published in November, and in it I’ve tried try to say something coherent about that relationship. Co-Illusion begins with two quotes by Trump from 2018 – the first of which is, “Just remember, what you’re seeing, and what you’re reading is not what’s happening.” He really has broken that aura of the image, and it’s very effective, because as he himself says in the second quote, “It’s always hard to beat the enemy when you can’t see it.” He and the massive media powers behind him have altered that relationship between images and belief, and that’s a big thing to do. But it’s complicated and hard to predict what’s going to happen next, because I do think that belief is primarily transitive – that belief doesn’t come from the thing itself; people project beliefs onto things and choose to believe in them. But all of these new forms of media have certainly had an effect, and the relationship between images and belief are starting to change.

Is our belief in photographs and images in general finally eroding?

I’m of two minds about that. On one hand, perhaps it is eroding; but on the other hand, this has been part of human experience for a very long time, and as long as we’re in these bodies, with these eyes and this optic nerve, belief in what we see will be part of it. Every time a medium changes there are people who say that this is the end of our belief in images. But it’s never true, because it’s not really about the medium itself – we want to believe, and we need to believe.

Do you foresee, or can you even imagine, any way to counter Trump’s control of the image space – are there ways that you think photography, photographers, images or image-makers can untangle this, or redefine the image space in itself?

Again I’m torn, because the more I see of what has been built, the likelihood of subverting or changing it becomes less visible or imaginable. But on the other hand, it doesn’t all go away all at once. Things change slowly, and consequently there’s still a lot of work that image-makers could do that could have an effect – and there are people out there working at the moment that are already having an effect. But the pressures are greater now, both on those people and the form itself.

Looking toward the upcoming 2020 election, do you see any signs of promise; are you optimistic in any sense, or have you encountered anything that gives you a spark of hope?

Oh sure, I find hope every day, because it’s still about people, and there are people out there doing the work every day. So culturally, I still have hope. Unfortunately, in a political sense, it’s going to come down to how many people vote. In the end, it’s really going to be about what voters under 35 years old do. If they vote in high numbers, there’s a chance for change. But if they don’t, I’m afraid that it may go into the next phase – which is very difficult to predict – but is going to be really bad.

And what about in terms of the image space or visual culture at large.

Again, I’m fascinated every day by what I see, and I’m sometimes surprised by new forms. But at the same time, I’ve always found that there’s a lot of conformity in the ways in which images are put out, and I’d like to see more innovation there. It’s hard to tell. My sense is that even though cameras are ubiquitous, and we now all have technologies in our pocket that are capable of generating and sharing high-quality photographs and video all the time, people see many more images, but only briefly. Most of the people I know, whatever their age, collect a lot of images, but they mostly don’t ever look at them again, or only in very limited ways.

In the end, single images seem to have less of an effect today than they did in the past, because they’re collected and archived, but not used. It’s a constant flow of imagery, rather than a discreet or singular experience of a single image, and I’m not sure what effect that’s having, or whether it’s diminishing the overall cultural effect of imagery at large; I just don’t know.

But Trump is a master of this, and of controlling masses of people through it – he’s been a student of it from the very beginning, and really knows how to do it. It was the sixteenth-century philosopher and new media prophet Giordano Bruno who said that it’s much easier to get masses of people to fall in love with you than to get one person to fall in love with you. And that’s how images work – they work on a mass scale – and in that realm, we’re watching a master at work for sure.