Heels: Through the Magnum Archive

Rosalind Jana analyses the gender codes, sex appeal, and subversive potential of the high-heeled shoe

In the seventh installment of her series delving into the Magnum archive, exploring its decades of documentation of vernacular style around the world, fashion writer Rosalind Jana here turns her attention to another item which has made a significant contribution to the history of fashion. Having previously reflected on the evolution of denim, the cultural highs and lows of leopard print, the revolutionary impact of nylon hose, the act of dressing up, the luxury and utility of gloves, and the cultural connotations of the dressing gown, Jana here considers the symbolism of high heels.

A surprising number of Elliott Erwitt’s photos go up no further than the knees. In a close up taken in St Tropez in 1979 three pairs of feet cluster together, each clad in heels. These are well groomed feet, the nails neatly painted. Their shoes, too, are carefully considered: leisurely, open-toed and easily slipped on, elevating their wearers several inches above the pavement. These are holiday heels, not designed for walking anywhere in a hurry. A photo from Paris in 1989 features an altogether more sensible pair of low heels worn alongside dark opaque tights and a small, white dog. Another from that same year, taken in New York, contrasts two Dalmatians and an excitable third pup in a spotty jumper with the houndstooth clad trouser legs of the figure holding their leads. The legs end in a pair of heels patterned exactly like the Dalmations: adding an amusing Cruella de Vil style touch to the scene.

Erwitt once wrote that “dogs make easy, uncomplaining targets without the self-conscious hang-ups and possible objections of humans caught on film,” and frequently photographed a great variety of canine companions both alone and alongside their owners. It is notable how often these latter photos take on a dog’s perspective – shot low to the ground, meeting these undaunted creatures at their own level, the busy human world around them reduced to an impersonal sea of ankles, shins, hems, boots, and heels.

Although there is a both an obvious temptation and reason to approach all forms of footwear in close up, the heel is perhaps the most frequent form of footwear to find itself depicted thus. The Magnum archives are full of images of heels tripping over pavements and strutting across stages, the angle of capture only made possible by a particular kind of crouch or downward tilt of the camera. Martin Parr does so in order to juxtapose brightly coloured footwear with the garish shades and patterns of the seaside town in which they stand. Peter Marlow’s photo of a boy playing dress up nods to the inherent artifice and coded femininity of the heel, the child’s small, skinny feet dug right into the toes of a pair of boat-like shoes to maintain balance.

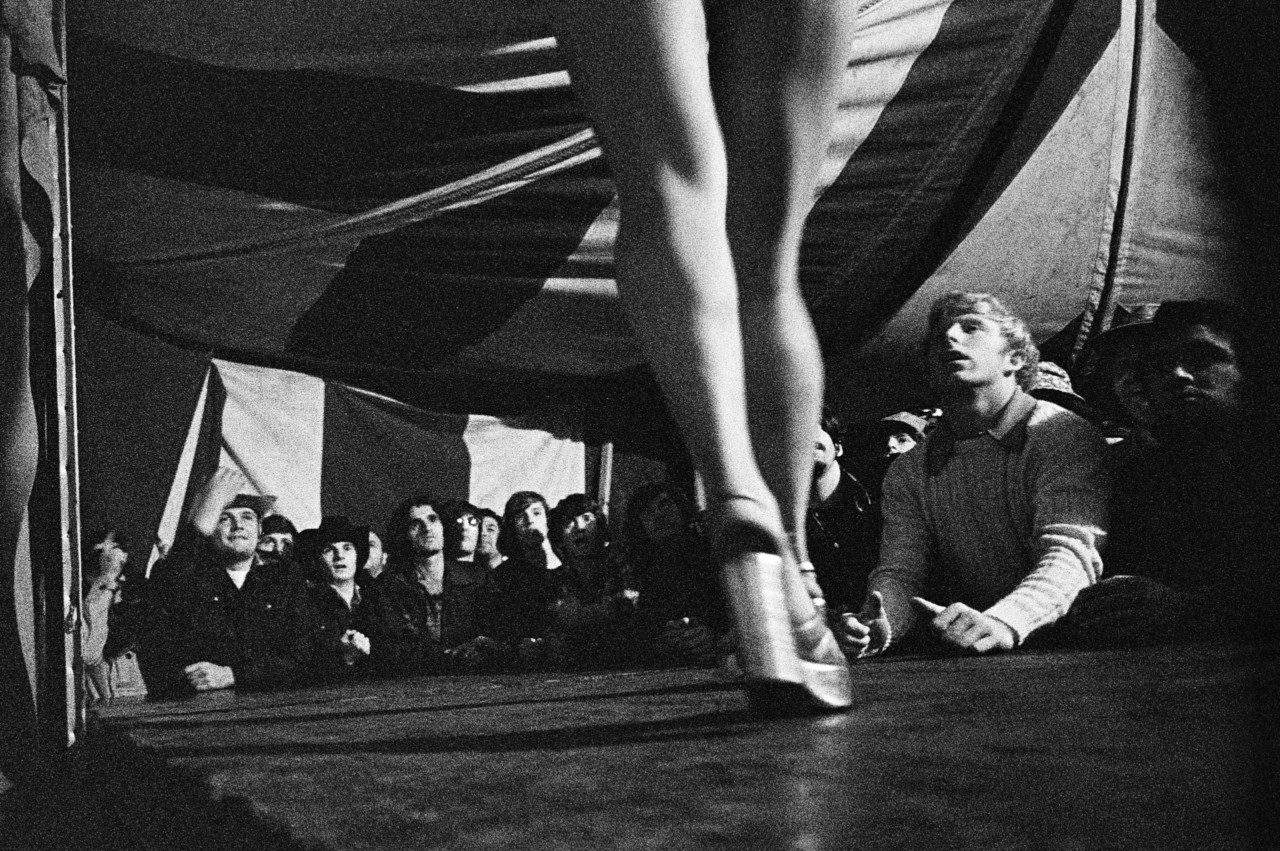

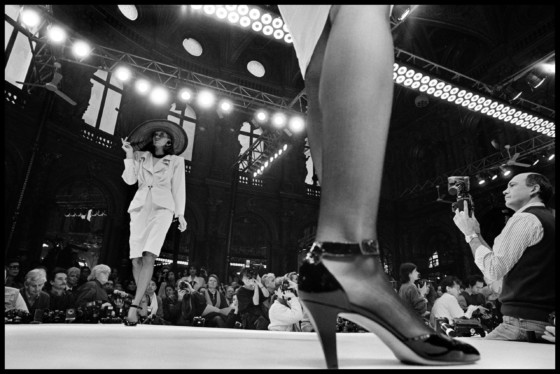

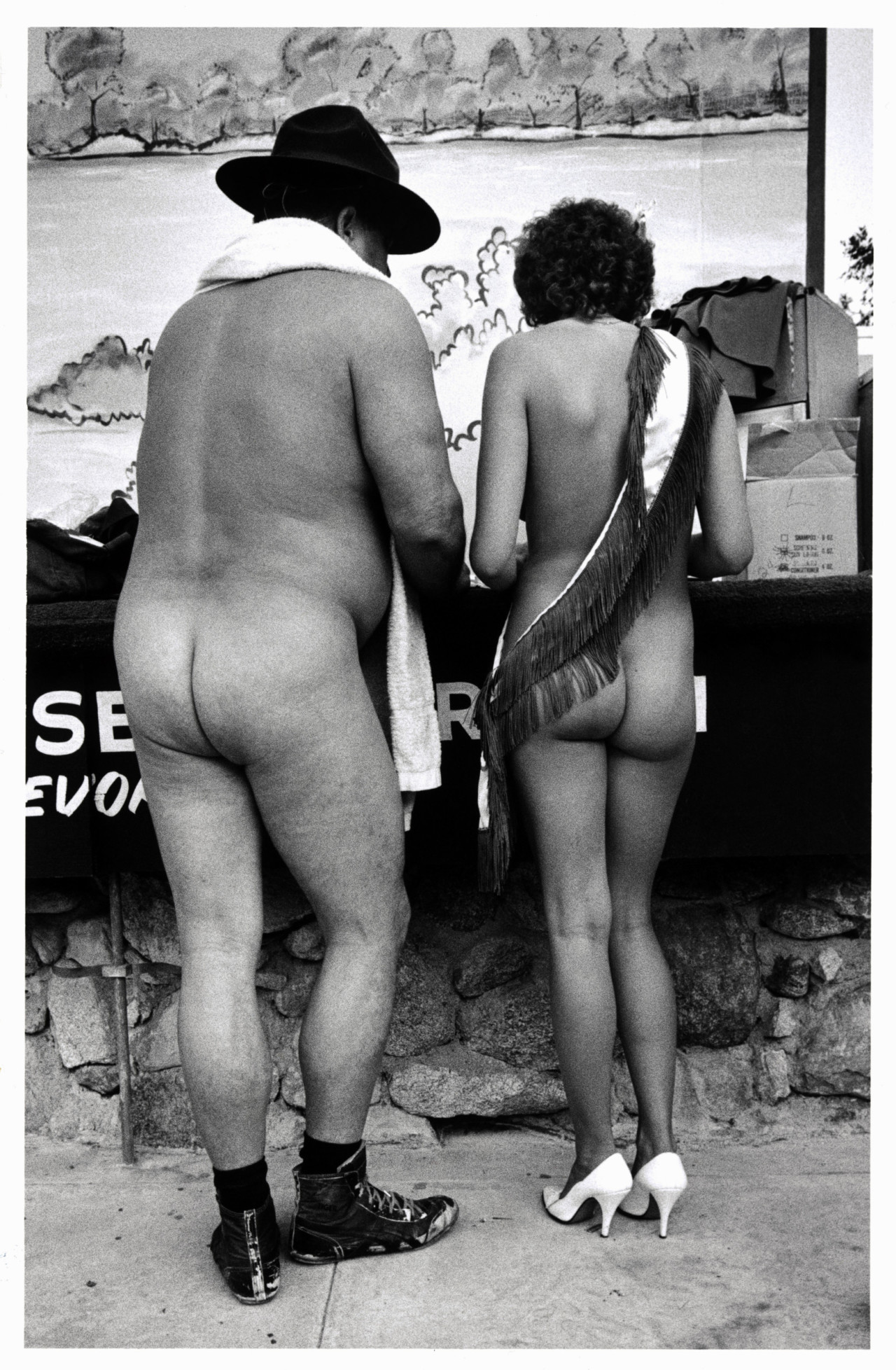

The visual pleasure derived from this particular eye level is intriguing. Often, it allows for both close focus and expansive background. In Abbas’ photos of Paris catwalks, curved black heels dominate the shots – audiences and elaborate sets framed by moving legs. A similar motion is present in Susan Meiselas’ photo of a stripper in Vermont in 1974, the performer’s slightly blurred platform heels and muscled calves facing off a tent full of eager men with eyes turned upwards. In another of Elliott Erwitt’s photos from 1960 a different trio – participants in what looks like a pageant, here cut off at the waist – stand contrapposto in swimsuits. The audience is almost eerily comprised of a single, sitting line of men and women, all clad in white, with rows of empty auditorium seats receding behind them.

"The visual pleasure derived from this particular eye level is intriguing. Often, it allows for both close focus and expansive background... audiences and elaborate sets framed by moving legs."

-

In these particular photos spectatorship itself becomes the subject: those being watched reduced to disembodied limbs and accessories, those doing the watching suddenly on show themselves. But heels do not always have to be witnessed by someone else in the frame to tell a story of observation. In Erich Hartmann’s photo taken at the Museum of Modern Art in 1963, the heels belong to two spectators lingering in front of a sculpture by Rodin. Both sets of high heels are rather sensible. Their shiny primness stands – literally – in contrast with the ruggedly hewn naked heels of the sculpture before them.

"Heels do not always have to be witnessed by someone else in the frame to tell a story of observation"

-

It feels worthwhile pausing on these questions of height and direction of gaze when considering the high heel, given the nature of the shoe itself. Heels have come to connote many things over the course of their existence. From flat, elevated platforms worn on the stage in Ancient Greece to militaristic use in 16th Century Persia, where heeled boots helped horsemen maintain better grip in their stirrups, through to the diminutive French King Louis XIV’s adoption of the red heel (most famously evidenced in his portrait from 1701) as both a practical and symbolic assertion of his stature, to more recent developments like the 1950s invention of vertiginous stilettos, heels have often been allied with notions of performance, power, and the transformative capacity of what we wear. In the latter stages of this history they have also taken on a distinctly gendered aspect, moving from something largely worn by men to an item deeply imbued with the expectations and pressures of normative femininity.

"Symbolic of restraint, suggestive of metamorphosis, and subversive depending on the feet they clad, heels offer many loaded meanings."

-

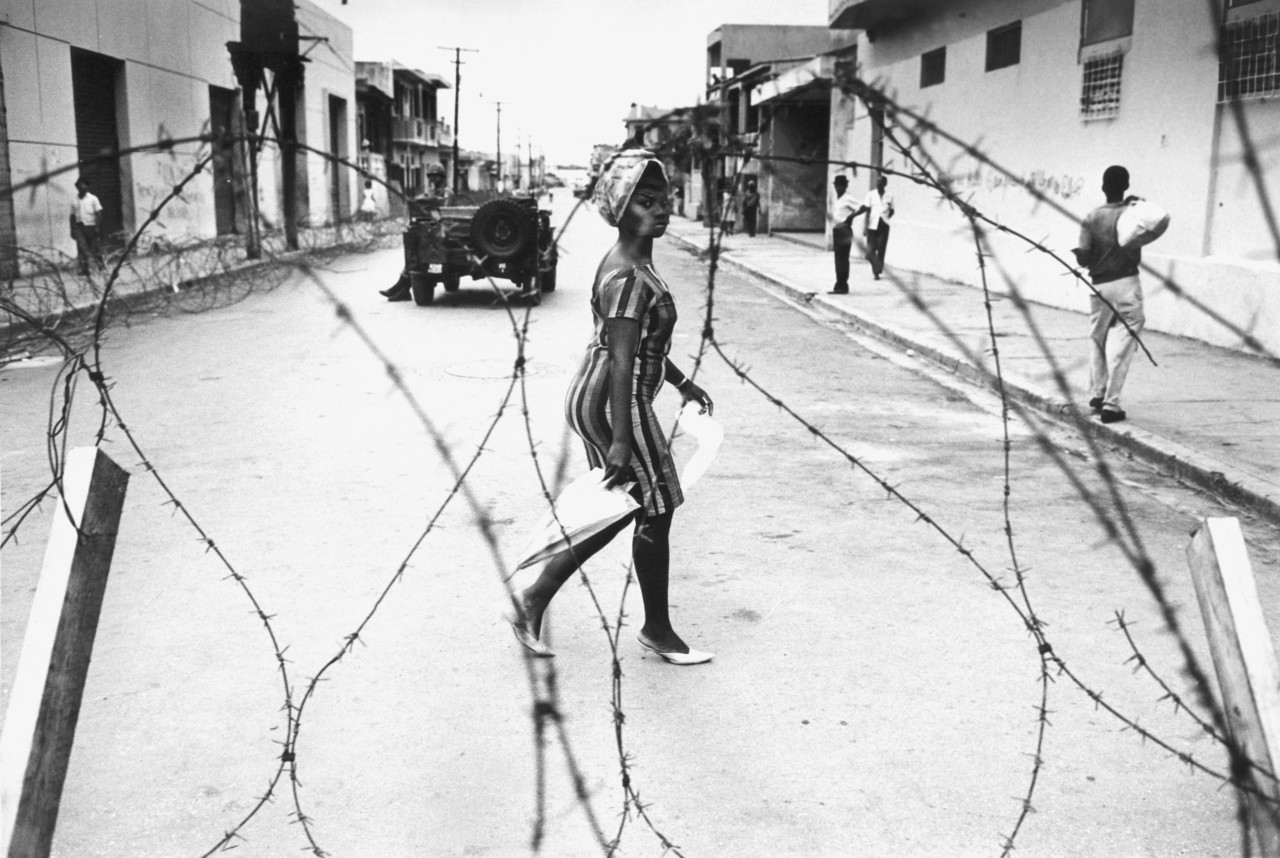

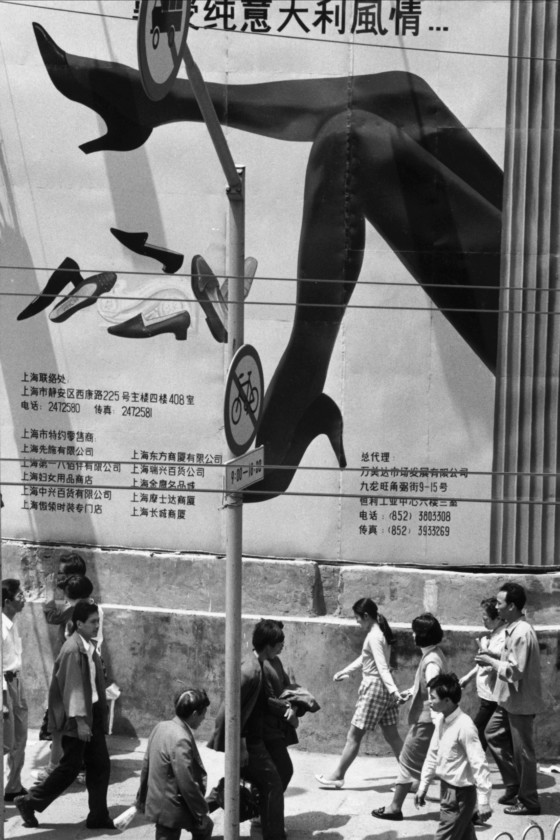

Which takes us back to gaze. Summer Brennan writes in her enlightening, compact book High Heel, “for better or worse, the high heel is now womankind’s most public footwear. It is a shoe for events, display, performance, authority, and urbanity. We have endowed it with a power to transform, and ours is a culture obsessed with female transformation.” In the world of work it is often considered professionally desirable. In the sometimes arduous work of fulfilling the prescriptive demands of womanhood, the high heel has become a key, and complicated, emblem. Symbolic of restraint, suggestive of metamorphosis, and subversive depending on the feet they clad, heels offer many loaded meanings.

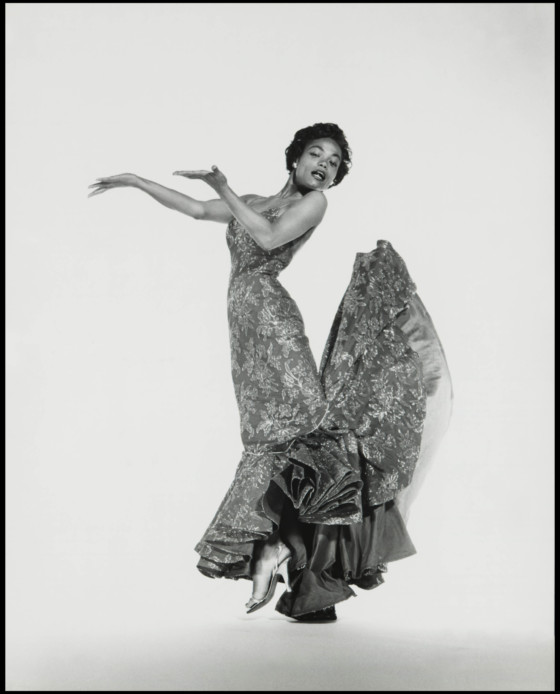

But Brennan is right. These meanings are often formed in public, or at the very least while the one wearing the heels is being observed. As with all items of clothing, meaning is often formed in the moment of being witnessed. Here, within the archives, we see some of those meanings play out. Performance is everywhere. Showgirls kick their feet high, a synchronized row of symmetrical legs and heels. Beauty queens take their prizes and pose for photos. Actresses jump and spin for the camera. Marilyn Monroe stands over that famous grate in that famous, billowing white dress, heeled sandals balanced carefully on the metal grille.

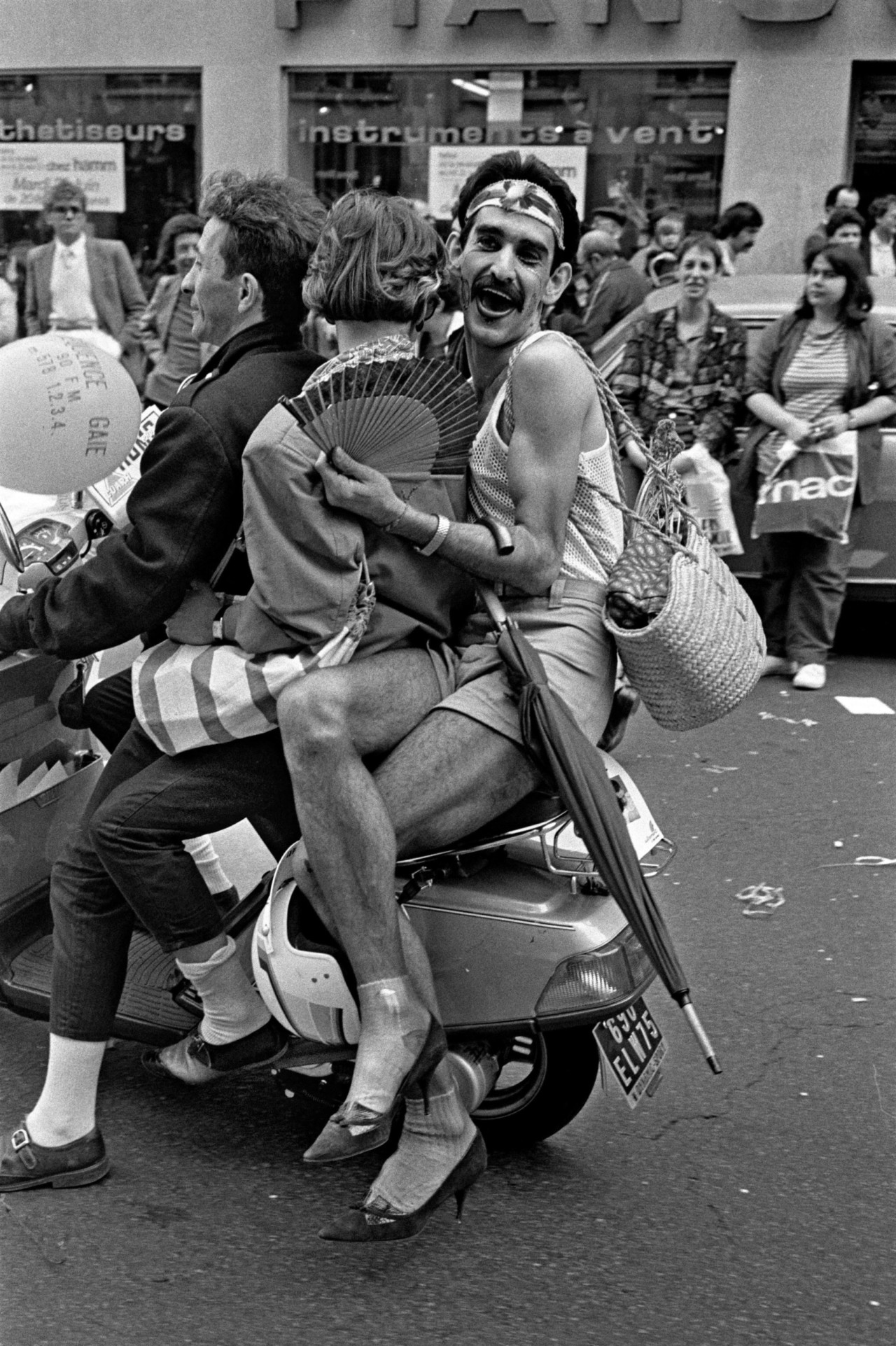

These performances are often ones of glamorous aspiration, especially when we take glamour in its original 18th century Scots meaning of magic or enchantment. High heels offer specific physical properties – the alteration of posture, legs and posteriors – and in doing so, also offer other, more nebulous kinds of heightening: promising to amp up the wearer’s desirability, or elegance, or ability to command attention. Often we might read these transformations as ones that cater to a mainstream male gaze. But they can offer provocation too. In Cristina Garcia Rodero’s photo at Spanish Gay Pride, a pair of white strappy heels dominate the frame. The transformative, and consequently enchanting, properties of heels exist very differently in the context of drag, cross-dressing and gender nonconformity, allowing for both imaginative refusal of expectation or categorization, and concrete assertion of identity.

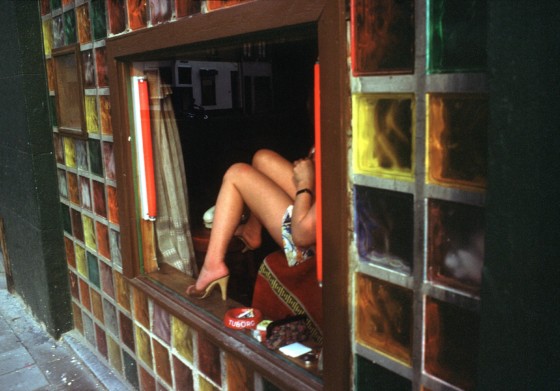

Dependent on context, they can also offer eroticism – especially as found in Harry Gruyaert’s glimpse of the red light district in Antwerp, Belgium or Bruce Gilden’s 2006 photo of a pair of sharp-toed black stiletto heels (stiletto, of course, named after a type of dagger) worn by someone whose ankles have been tied with rope. A widely recognized form of fetish, the contortions of heels have long been allied with sexual anticipation and gratification too.

A truth about heels – one linked in no small part to their position as a fetish – is that they are regularly very uncomfortable. They are one of the few forms of footwear that one has to be taught to walk in. Often, this requires practice, as well as an acknowledgment of one’s own, increased fragility when elevated by several inches from solid ground. To perfect and command the gait required by heels is a real art. An art that can also have long-term health consequences, given the impact on one’s spine. The more immediate practicalities of this discomfort are captured in Martin Parr’s photos of heels drunkenly kicked off, sometimes replaced with flip-flops.

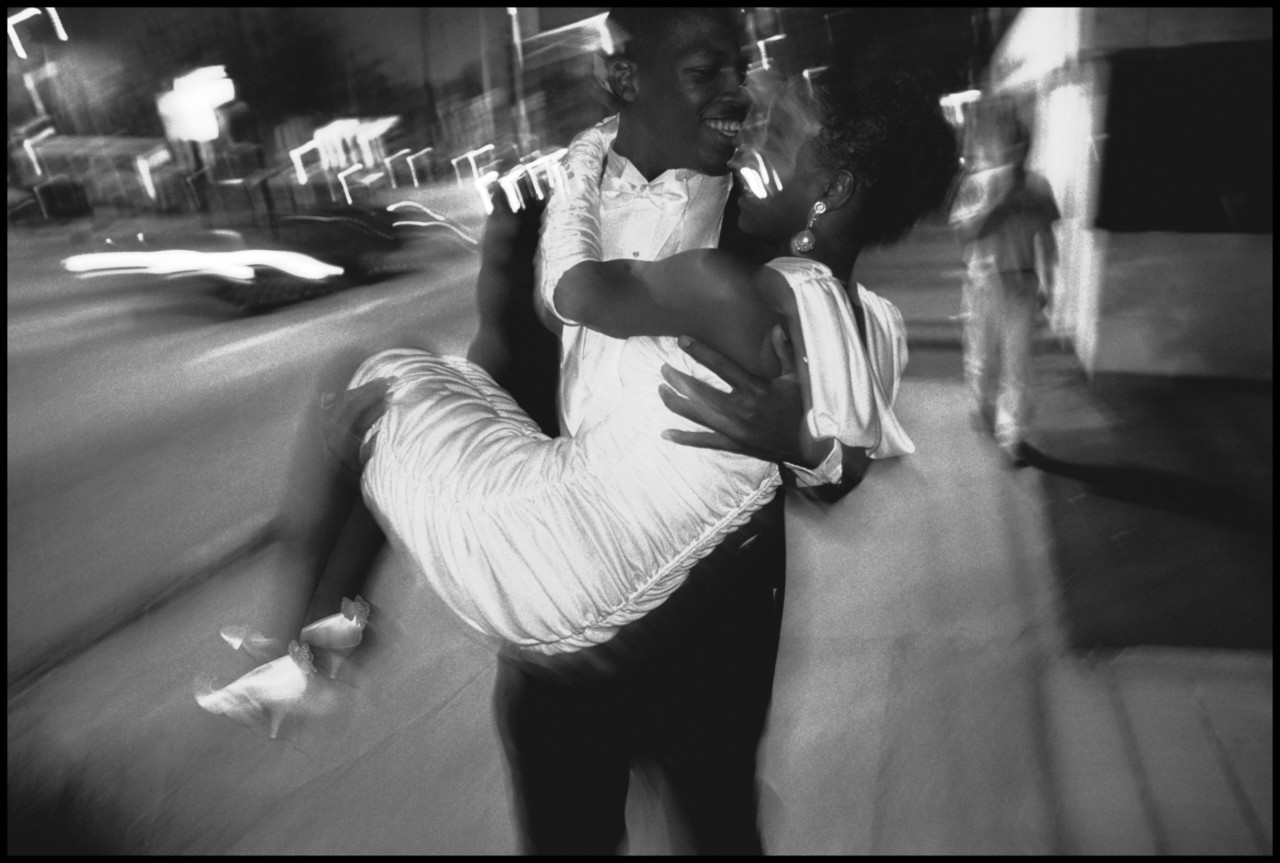

Elsewhere, there is a wonderful tenderness to Eli Reed’s 1993 photo of a couple on a night out after their graduation. A young man dressed in a tux cradles his partner: the shiny fabric of her dress, gloves, and shoes with bows at the back reflecting the blurred streetlights behind them. Maybe he is carrying her because she is tired, or they want to be close, or both of them are simply caught up in the exuberant motion of the evening. But there is a suggestion too that this gesture may be a generous one, potentially relieving her feet from the reduced speed and heightened pain that can come from a surprisingly complicated kind of footwear.