The Symbolic Construction of a Territory Where Violence Penetrates All

2020 Magnum nominee Yael Martínez's depictions of dreams and nightmares give voice to experiences of loss amid the fraying of contemporary Mexican society

Yael Martínez, a former Magnum Foundation fellow and recipient of The World Press Photo Award for long-term projects – as well as nominations for the Prix Pictet and the ICP Infinity Awards – has, since 2013 been exploring the tangible and spiritual impact of violence on families in Mexico, including his own. The photographer’s loss of three family members to organized crime set him on a path of exploring the deleterious effects of the drug trade upon his native state of Guerro, and Mexico at large. Here Martínez discusses rendering dreamscapes in photographs, the benefits of a multi-media approach to a long-term project and transforming the destruction caused by bereavement into something generative.

This is the first in a series of interviews with Magnum’s five 2020 nomiees. Learn more about the updates from the collective’s 2020 AGM here.

The above image, from Martínez’ project Firefly – discussed at length below – is available now as part of the Magnum Editions Posters collection. You can explore this new, limited edition collectiom in full on the Magnum Shop, here. You can also explore a selection of Martínez fine prints on the Magnum Gallery, here.

Could you tell us about your path into photography, and at what point an interest became a profession, and how that profession then became what appears now to be more of a mission with your work?

I discovered that I wanted to become a photographer when I saw the work of Josef Koudelka and W. Eugene Smith. At the time I was just a boy and I had never held a camera. I took my first photographs when I was 17 years old, with a plastic camera that belonged to my sister, which was the only camera that we had in our family. With those photos I tried to make a story and applied to study Visual Arts at a university in Mexico, but I was rejected because I did not have the knowledge or skills to become an artist.

I realized that we are not born with these skills, but we can learn them. Art can be taught.

After taking up classes on commercial photography in a technical college in Mexico, I started working as an assistant to an architectural photographer – and did that for two years. In 2006 started working alone, trying to make a living. With the money that I earned I was able to buy my first digital equipment: a camera, a lens, and a computer.

After a year in the States I returned to Mexico and started working on several personal projects; these projects helped me enter into different photography programs that helped shape and develop my work as a photographer. Two of these programs took place at Centro de la Imagen in Mexico City, and La fototeca nacional de Pachuca. But the ones that really defined me as a photographer were at the Manuel Alvarez Bravo´s Center and The Center for the Arts of San Agustin. Both created by Francisco Toledo in Oaxaca, Mexico. Considered one of the most important artists in the country, he is also known for his work as a social activist. He is responsible for opening up opportunities to Mexicans to study arts, regardless of their social status.

Thanks to these spaces in Oaxaca I have had the opportunity and privilege of being mentored by great names in photography such as Mary Ellen Mark, Antoine d’Agata, Charles Harbutt, Maya Goded, Joan Liftin, Gerardo Montiel Klint, Eniac Martinez, Pablo Ortiz Monasterio and – in 2019 – I was fortunate enough to be selected as one of the nine fellows from around the world to be part of the Magnum Foundation Photography and Social Justice Fellowship with Fred Ritchin and Susan Meiselas as my mentors.

"My work focuses on communities fractured by organized crime, in a physical and psychological sense. I am trying to create work that represents the connection between absence and presence"

- Yael Martínez

Your best-known project – for which you have won numerous international awards – is La Casa Que Sangra (The House That Bleeds) – could you explain the project’s origins, and its history to date?

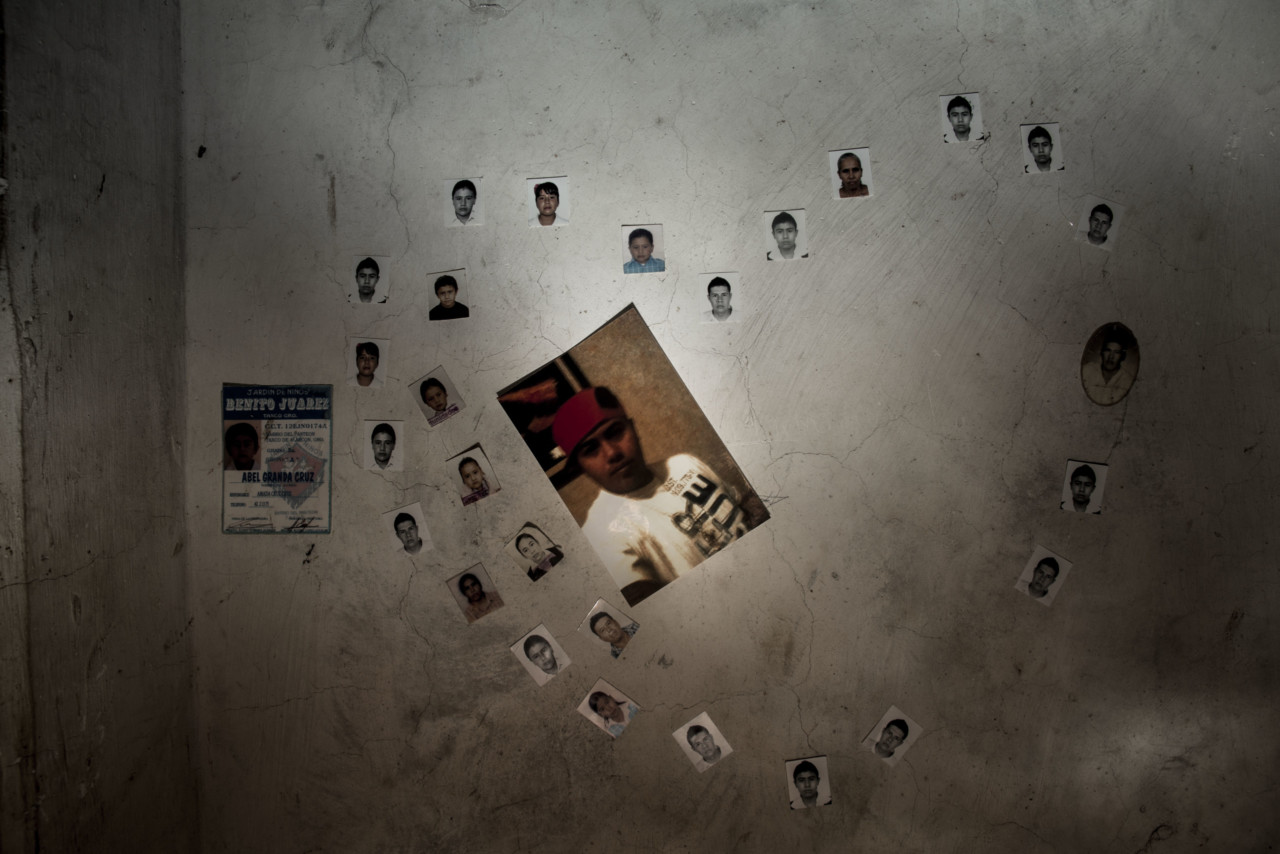

In 2013 I lost three members of my family, they 18, 19, and 23 years old. After that happened I began photographing my own family and others who had also had loved ones either killed or disappeared. I am exploring a path that will help me generate a historical memoir of our lifetime: a testimony through which I can discuss all these layers of reality that shape my country. My work focuses on communities fractured by organized crime, in a physical and psychological sense. I am trying to create work that represents the connection between absence and presence, and this state of invisibility in a symbolic manner, working with the concepts of pain, emptiness, absence, and forgetting. I’m interested in exploring the symbolic construction of the territory where violence penetrates all and this violence crosses the physical and spiritual space of those who inhabit it. The territory as an analogy to a body or space that could be a house, a person, a family, a community or a country.

I intend to create work that reflects the time we live in and responds not only to the Mexican identity, but also to the Latin American identity. I believe that when photography engages with education, culture, and politics we can create a better world with different voices and perspectives in life.

"I started working with the concept of resilience and how we as human beings can transform a black energy into a positive energy. A light in the darkness. That’s when Firefly came about"

- Yael Martínez

Firefly – another project – sees you illustrating your photographs with pinpricks, allowing delicate threads of light to emerge from the images. Is that part of The House The Bleeds, or distinct from it. How much do your projects intertwine in your mind?

After six years of working with the families of missing people I was trying to explore a different perspective on the concept of resilience in these families and individuals that have been fighting against violence in their communities for several years; and last year I got an invitation from a curator – his name is Claudi Carreras – to participate in an exhibition about the concept of night in Latin-America. I proposed the idea that I had in mind to him and started working with the concept of resilience and how we as human beings can transform a black energy into a positive energy. A light in the darkness. That’s when Firefly came about.

I would describe it as the next chapter of The House That Bleeds.

"I chose different approaches in order to develop an image for the audience that is as close as possible to my experience"

- Yael Martínez

You used the idea the other day – when speaking with Magnum staff – of having different types of photography come together ‘like a choir’ – how important was it for you that your exploration of your own loss and Mexico’s situation wasn’t a ‘straightforward’ photo reportage project – that I included self-portraiture and illustration?

Photography has for me been a life experience; and I always try to develop an image can be close to that experience; that is way I chose different approaches in order to develop an image for the audience that is as close as possible to my experience.

Restrictions on what can be photographed can also help you to redefine an idea. What is important is to preserve the core of the idea and to follow our perception of reality. There is not one-reality, but there are many different ones existing in the same time.

What specifically, can a non-literal approach help you capture that more descriptive one can’t?

I think as photographers we can work with both approaches, but what is more important is to create a specific experience when telling the story; this is the key to engaging the audience.

"For me it was really important to transfer those images from the nightmares into photos"

- Yael Martínez

There’s a surreal or dreamlike or surreal aspect to some of the images from THTB – is that intentional?

Yes, at the time I made the work my family and I were having nightmares and – again – for me it was really important to transfer those images from the nightmares into photos.

I wanted to create a sense that reality and dreams are as one.

The disappearances of your brothers-in-law happened in the same vicinity as the – now – famous abduction and disappearing of students from Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers’ College… How did that later event impact your own thoughts about documenting your family’s loss – if at all? Did it go from a personal project to a project about all of Mexico – or was it for you that big from the outset?

In the beginning I was trying to find a path to understand this tragedy in my own family, but after I began working with the other families the project expanded from a personal one to dealing with social issues all over Mexico.

The process of the project was slow. I have put all of my personal life into it and takes time to understand the situation you are going through.

How have the rest of your family responded to your work on this? Were there fears about your safety, objections to your publicizing this loss?

In the beginning we all had fears about our security, but after a year we decided to continue working with the project because for us was important to talk about these issues in our community and in the country at large; I always try to be honest and clear with all those I work with on the project because I see my family and the families who are opening the doors of their lives to me as my main collaborators.

The fears don’t disappear but the greater urgency is the need to confront these issues to give closure to grief, to transform the energy.

"Now, more than ever, we need to create an extensive narrative of our history to re-construct our past, present and future."

- Yael Martínez

Speaking about the House that Bleeds – you have said that the project explores just one aspect of life in Mexico today that is fraying at the fabric of society. What are the other pressures you see on Mexican society, and how can photography – and art in general – be used to counter these negative pressures?

We are living a complex time in Mexico and in different latitudes of the globe; there is so much poverty and social injustice, and there has been for so many years, that we are still dealing with all the bad decisions of the people that came before us. But I have learned all over these years that art and photography can be a vehicle for social transformation.

Mexico is a country that is photographed a lot, but often by outsiders – how important is it that a country’s struggles are documented also from within – and by extension, how do you feel about the majority of images of Mexico seen around the world? Is part of your motivation to add to or change that visual conversation?

In the representation of the world, and of reality, we have found that we can only add a piece to the puzzle. To understand our world we need to add more perspectives and more ways to see our reality. Adding diversity and different perceptions will help us to create a better understanding of our reality and the times we are living through. It is necessary to create a dialog between more than one or two points of view. Now, more than ever, we need to create an extensive narrative of our history to re-construct our past, present and future.