The Camera Ministry of Khalik Allah

On following a higher power to document black life across the diaspora – an interview with the new Magnum nominee

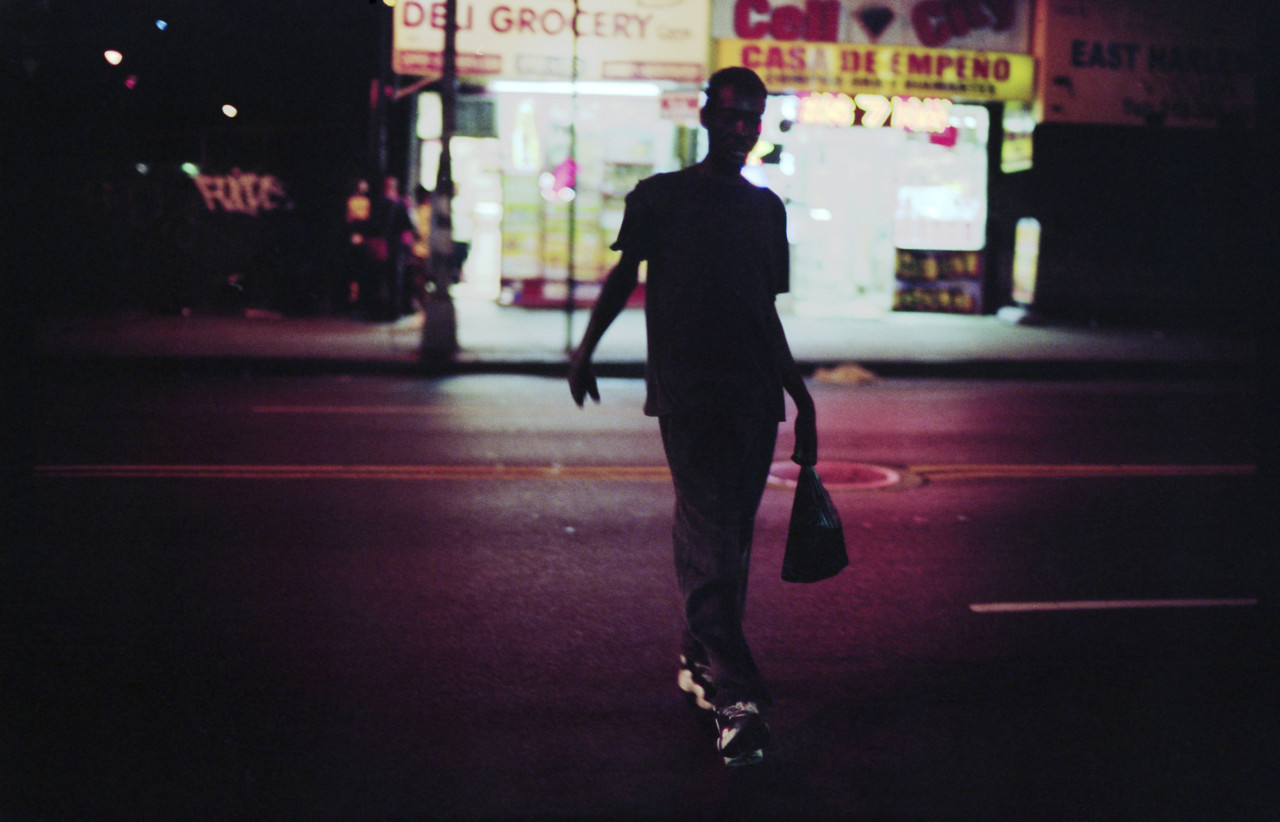

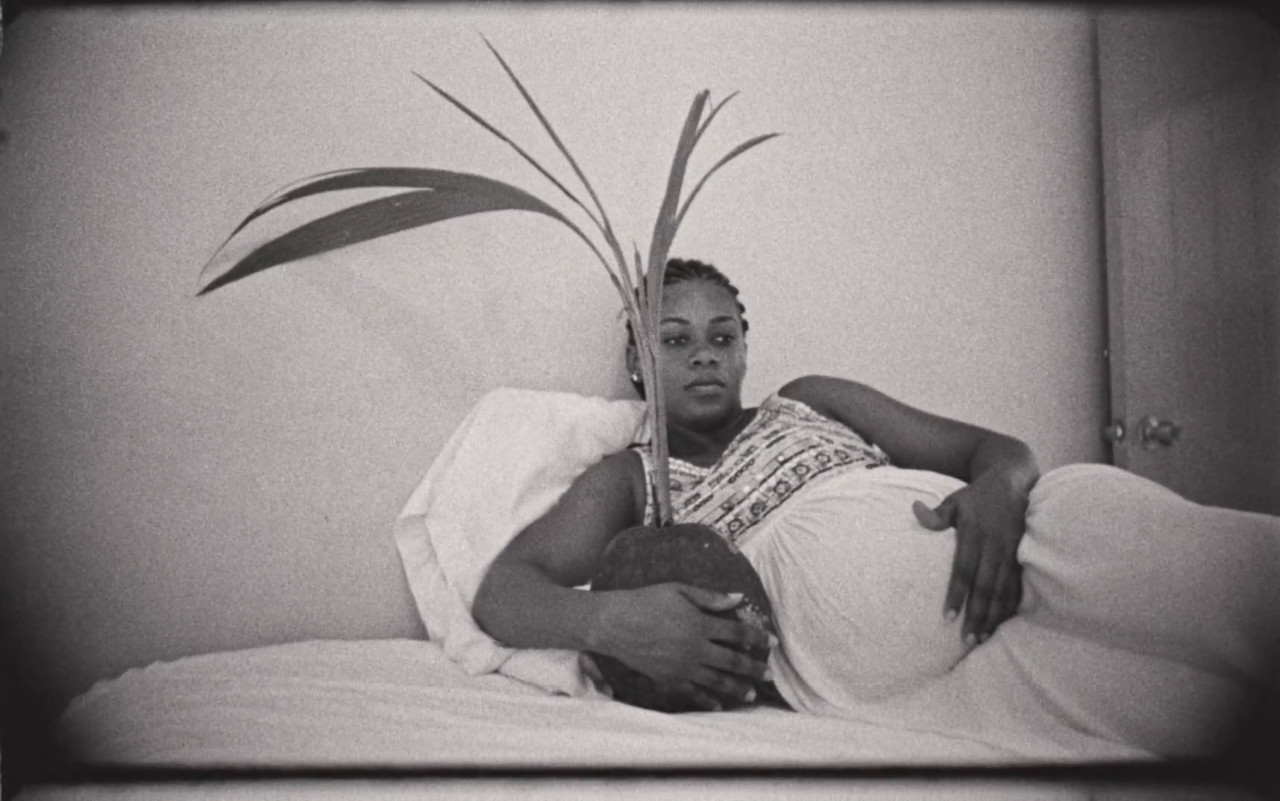

Hailing from New York, Jamaican-Iranian artist Khalik Allah is a self-taught photographer and filmmaker documenting black life across the diaspora. In his hands, the camera illuminates the spirit made flesh, liberating the soul of his subjects from the burdens of their social circumstances. Whether making images in East Harlem for the film ‘Field Niggas’ (2014) and his first book Souls Against the Concrete (University of Texas Press, 2017) or traveling to the Jamaican countryside to explore his family roots in ‘Black Mother’ (2018), Allah invokes the teachings of the Five-Percent Nation in his work. In summary Allah describes the Nation – which emerged in Harlem in 1964 and in which he grew up in as “an educational outreach movement.” He continues: “Its teachings are directed at young black men and women to give them ‘Knowledge of Self’; to uplift them by restoring them to the awareness of black people’s contributions to world history prior to American slavery.”

Here, the 2020 Magnum nominee discusses the importance of staying true to his vision and following his own path to co-create stories of love and innocence with his subjects.

How did you get your start making images?

From ages 14 to 25 I was focused on motion picture. I begged my mother for a Sony Hi8 Camcorder after getting left back in the eighth grade. That was the first camera I ever owned. I made my first short film, ‘The Absorption of Light’ (2005), and started doing music videos for hip-hop artists. In 2010, I made ‘Popa Wu: A 5% Story’, with the patriarch of the Wu Tang Clan. That film was a strenuous project and afterwards I didn’t want to make films anymore, but I still had creative energy. That’s when still photography became important to me.My first camera was a Canon AE1 SLR that my father gave me. I liked the metallic body, glass lens, manual settings, and weight made me take it seriously and look at it as an art form.

"The [stills] camera was an extension of filmmaking, but I had to learn about framing a single image. It made me more focused, thoughtful, and mindful"

- Khalik Allah

How does your work as a filmmaker inform you work as a photographer and vice versa?

The aspect of filmmaking that transferred over to photography was the cinematographer in me. I have always shot my own films. The [stills] camera was an extension of filmmaking, but I had to learn about framing a single image. It made me more focused, thoughtful, and mindful. When I’m out on the streets I like to think of a story that I’m telling on one roll of film. I like to shoot in a way that the photographs all relate to one another.

When I went back to filmmaking I had a new state of mind because photography fine-tuned me. I developed a whole new technique with the films ‘Field Niggas‘ and ‘Black Mother’. These projects are photographer-style documentaries: portraits of people, sustained attention on one subject.

You describe yourself as a visual MC — can you expand upon that?

When I am on 125 Street and Lexington Avenue [the junction in Harlem, New York, where both Souls Against the Concrete and ‘Field Niggas’ were made], I am always listening to classic ‘90s hip-hop like Big Pun, Mobb Deep, and Nas. I look at my photographs as lyrical pieces. Hip-hop is a marriage of the lyrics and the beat; my work is a marriage of myself and the streets, with my camera aligned with what I am documenting.

I’m not shooting nudes or beaches, things that may be considered beautiful. I am shooting at nighttime in East Harlem. To build those relationships you have to have fortitude, be able to stand on your own, hold yourself down, and speak to people. I’m what people consider a street photographer, but I think what I’m doing is deeper than photography itself. There’s a lot that doesn’t get captured on the emulsion, such as the conversations. This is all a form of MC’ing to me because hip-hop started out on the corners.

"I think that beauty is everywhere. It depends on the decision to find it, focus on it, and accept it. Perception is always a choice"

- Khalik Allah

How would you describe your concept of beauty?

I think that beauty is everywhere. It depends on the decision to find it, focus on it, and accept it. Perception is always a choice. It seems that we are feeding off what our senses tell us is reality, but we choose what we see. When we look outward, we see a reflection of what we first witness inside ourselves. When you turn inward, your inner world is naturally unique. As long as I draw on that well of inspiration it’s not going to run dry.

Growing up in the Five-Percent Nation, one of the earliest things we were taught was not to take anything on face value. There’s so much knowledge aimed to manipulate black psychology. The first thing black students are taught is that they were slaves. From second-grade on, your self-esteem is a couple of notches below the white students because you’ve been told you are inferior. That sticks with you and follows you into your adulthood.

My spirituality primarily became the guiding light in all of the work I do and awakening people to a higher reality. We’re living in a world of racism, projection, hatred, and fear. Fear binds the world and forgiveness sets it free. My work is all about forgiveness. I’m going into a neighborhood where there’s a lot of homelessness and drug addiction. The circumstance is like a veil that is obscuring the deeper light a person has. That takes a level of vision just to choose to see that. Many people don’t bother with a lot of my subjects simply because of the surface layer.

How crucial is having a personal connection to the people you are documenting?

In some of the spiritual texts I study, it says the way to God is found with empty hands and an open mind. I don’t greet my subjects as though they are defined by their circumstances. A lot of my subjects are depressed. They are dealing with being deprived of social equality. In that depressed state they turn to drugs and crime because they feel desperate. When I come through with my camera and I find somebody lying in a puddle of urine, I ask them to stand up and walk with me into the light to take their photograph

That began to define what I was doing, which is what I call “camera ministry.”

"I am accepted because there’s nobody trying to tell their story honestly because of fear. That’s why I chose 125th and Lex to become then nucleus of my photographic work. I am shooting at nighttime in a black neighborhood. Those are two things people are afraid of"

- Khalik Allah

What aspects of black culture can only be known and told as an insider in your view?

I like to highlight that we are a loving people; we are generous, happy, peaceful, righteous, and noble. Often times the circumstances are pushing us in ways that go against our nature. My photography and filmmaking are radical because I am trying to show love. I see a lot of people who have formed a family and none are physically related but just because they are in a similar circumstance of being homeless or addicted, they forged this family bond.

I am shooting at nighttime in a black neighborhood. Those are two things people are afraid of. I’m trying to turn that on its head and show that there is nothing to fear.

What is the relationship between your works made in East Harlem and in Jamaica?

"What I was saying about black people in general — the open-heartedness, kindness, gentleness, creativity, and goodness — Jamaica has all of those things in abundance"

- Khalik Allah

Could you speak about the spiritual aspects of Jamaica you wanted to document in Black Mother?

Jamaica has all these clichés and tropes: reggae, marijuana, and Rastafarianism but there’s so much more to it than that. It’s a small country with a huge influence on the globe and the heart of the people is what makes it a bigger place than what it physically is. What I was saying about black people in general — the open-heartedness, kindness, gentleness, creativity, and goodness — Jamaica has all of those things in abundance.

‘Black Mother’ is a collection of impressions reaching back into my childhood; some of the footage goes back to when I was shooting on the Hi8 Camcorder. My grandfather was a parish councilman deacon in Clarksonville Baptist Church, which is the primary church in the film. I punctuated the film with prayers and felt that was the greatest way to express the soul of the island from my standpoint.

"What I would see in the countryside [of Jamaica] was a level of spiritual expression that I didn’t always see in the cities. When I set out to make this film that’s what I was aiming at"

- Khalik Allah

You once said you didn’t think you wouldn’t be accepted in the worlds of art and film. What do you make of the acclaim you work has been receiving?

To be recognized as a black artist with this type of understanding of history is important to me. I don’t want to become successful just because I’m a black person doing something not a lot of black people do; I want to become successful because I’m really good at it. Not a lot of black people have joined Magnum. I feel that I was accepted because Magnum wants to become more inclusive, but [also that the collective] did not compromise their artistic integrity by accepting me only because I am black photographer, but because my work truly warrants it.

Coming up in the Five-Percent Nation and hip-hop culture – where everything was about being original – a lot has to do with tenacity, remaining true to vision, and not giving up or giving in. I didn’t do anything outside of myself to become accepted. I step back and let my inner guide lead the way in my work. The only thing that will satisfy me is doing God’s will.