Die Vier Hoeke: Inside the four corners of the South African prison system

The political and conceptual context for Mikhael Subotzky’s project Die Vier Hoeke (The Four Corners)

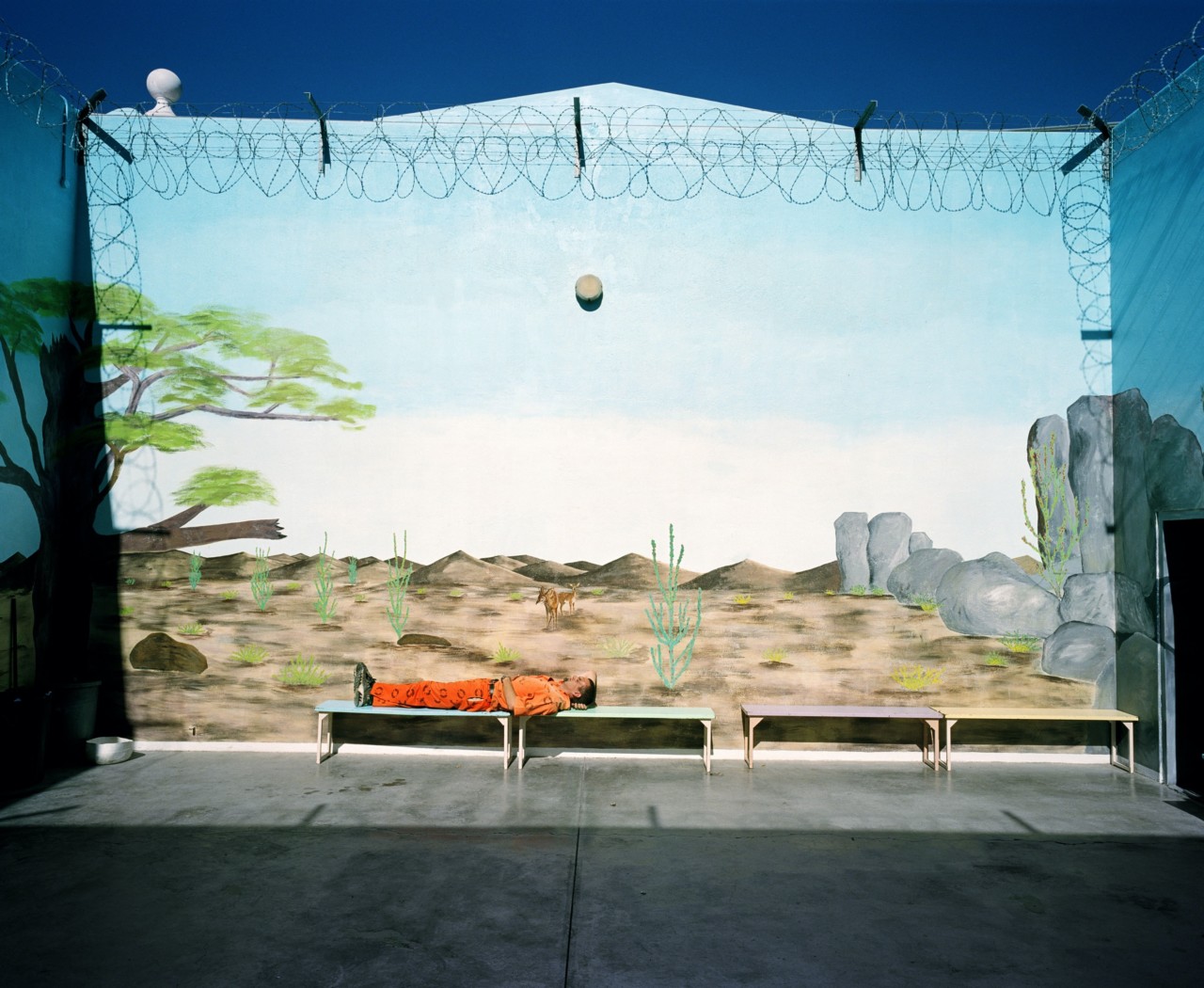

Several questions arise upon viewing the photograph taken by Mikhael Subotzky, titled ‘Jaco, Beaufort West’ (2006). In what circumstances did this image materialize? How did the artist gain access to the prison? Who is this man, lying despondent, in front of a luminous mural depicting a scene so different from the architectural reality he finds himself in? It’s an image that is both alarming and enticing. The tapestry of emotion is woven: the utopian backdrop is alive with color, richness, possibility. The figure, on the other hand, appears hapless – exhausted.

In this image, the disparity between the two colliding environments makes an astute commentary on the starkness of prison life. It demonstrates the harshness of incarceration, but also the imperative to imagine somewhere else, a utopian setting, or in this case a vivid natural landscape. But the photograph also binds the viewer to a feeling of uncertainty.

In an attempt to further understand this image, we spoke to Subotzky about his project Die Vier Hoeke (The Four Corners), the role prison photography plays in questioning who looks and how we look, and the camera’s struggle with representation.

Born in Cape Town, 1981, Subotzky has undertaken several ambitious projects in the last fifteen years. These include Die Vier Hoeke (2004) Beaufort West (2008), Retinal Shift (2012) and recently, Massive Nerve Corpus (2019). All of which, through differing approaches, question societal institutions, control, belonging, and notions of visibility. There is an enduring sense of curiosity and uncanniness when viewing his impressive body of work; a sense of raw emotion, integrity.

Die Vier Hoeke was Subotzky’s first project and described visits to a number of prisons in South Africa. After being inspired by what he described as the “humanistic nature of documentary photography”, Subotzky became interested in photographing incarceration, and crucially, in making visible what is often hidden from wider society.

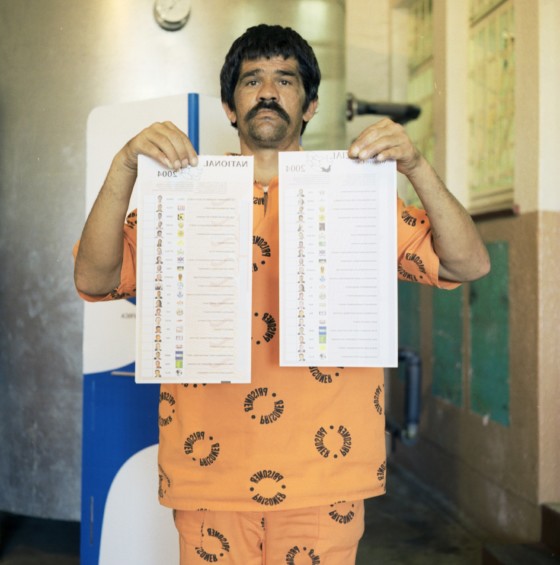

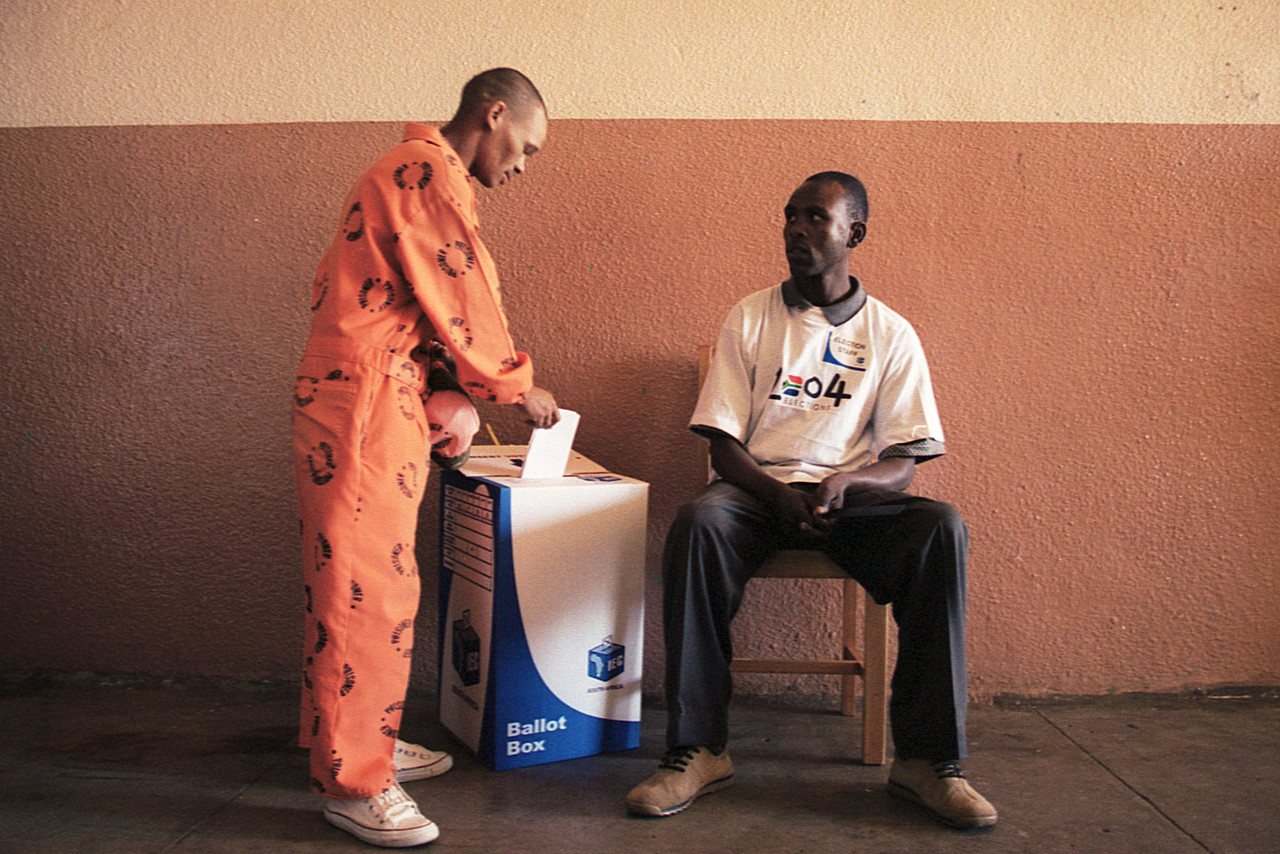

“Die Vier Hoeke is part of a bigger artistic commitment to exploring the penal system, ignited by a time of judicial tension back in 2004. I became very aware of issues of representation, and the challenges of making images in a part of society where power balances are particularly skewed,” explains Subotzky, before commenting upon the contemporary political context that spurred the project onward. “In 2004, the government – many of whom had been imprisoned themselves– were trying to remove prisoners’ legal right to vote.” The ANC, the party led into power by Nelson Mandela, and at that time headed by Thabo Mbeki, was banned by the state during the apartheid era; its representatives had all experienced prosecution or exile during the 1960s, ‘70s and ‘80s. It was these ironies in the political system, combined with disparities proceeding post-apartheid South Africa, and the extensive mass incarceration throughout the country which caught Subotzky’s interest:

“There was a constitutional court case that challenged whether the government could take away the right of certain prisoners to vote. The court case eventually reaffirmed their right. This was hugely ironic to me as many of our political leaders had spent time in prison. Our iconic president Mandela had said ‘the measure of a society is not how you treat its highest citizens, it’s how you treat its lowest ones’.”

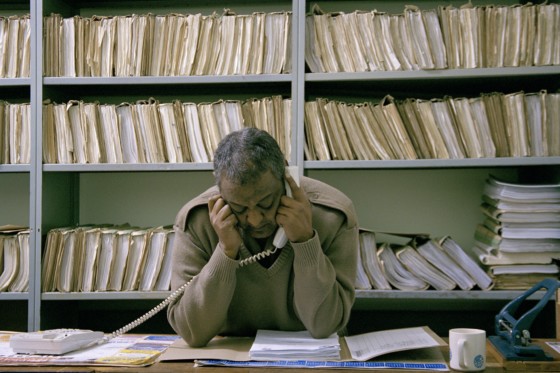

It is from this political context that Die Vier Hoeke began. After meeting people from the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC), Subotzky embarked upon the lengthy task of entering prisons to document the voting debate. While on holiday, he randomly met people who helped him gain access to a small rural prison to take portraits of prisoners holding up their ballot papers. He continues, “I then got in touch with the correctional service department, to get access to bigger prisons”. Subotzky was committed to making direct contact with the prisoners – not just photographing them – but also attempting to impact on their lives. After communicating with a prison officer, of “progressive thinking”, as he described, Subotzky began organizing photography rehabilitation workshops in the notoriously dangerous Cape Town prison, Pollsmoor, situated in the suburb of Tokai. He was only 24 years old at the time.

During the classes, inmates were permitted to use cameras he provided – objects usually banned from entering the prisons. Subotzky’s intervention of bringing cameras into prison for rehabilitative measures gave prisoners some liberties which had otherwise been stripped. Making interpersonal connections was his priority, beyond creating documentation. Subotzky explained, “Lots of relationships were formed then, which I still maintain today. I put the relationships first and the photographs second, as a byproduct of the engagements”.

"Lots of relationships were formed then, which I still maintain today. I put the relationships first and the photographs second, as a byproduct of the engagements"

- Mikhael Subotzky

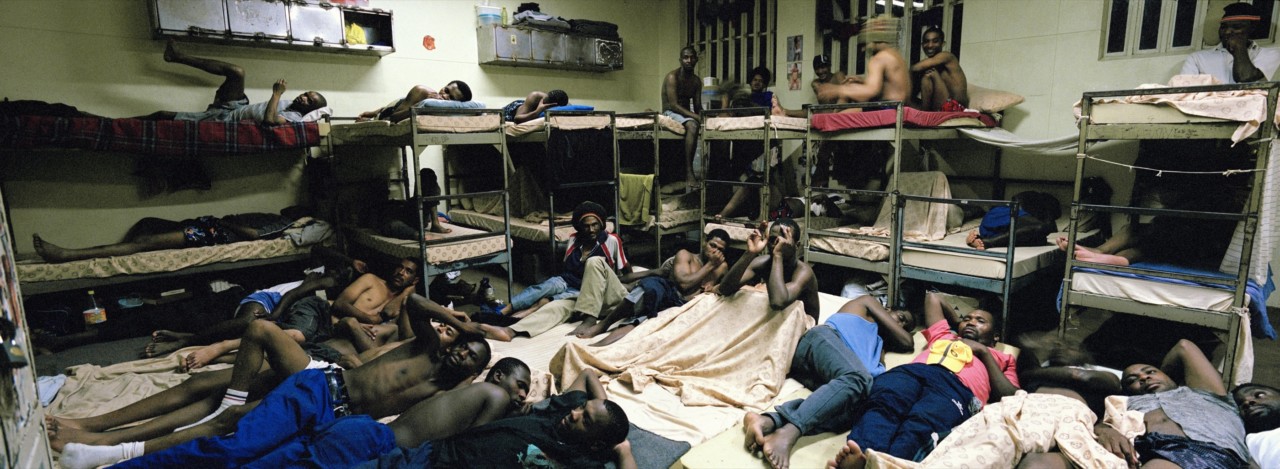

It was obvious how different the conditions were at Pollsmoor. He explained, “I was photographing cells designed for 16 people, with 80, 90 people living in them”. Designed during the apartheid era, Pollsmoor still functions as a maximum security prison today, and is still overcrowded, with some cells at 300% over capacity (as reported by CNN in 2016). Many of the photographs from Subotzky’s Die Vier Hoeke were captured there, such as the unsettling ‘Jonny Fortune bathes in the industrial washer in the laundry’ (2004). Subotzky’s first exhibition took place inside the prison, on April 17, 2005, the 11th anniversary of South Africa’s shift to democracy. “The exhibition was in Mandela’s old cell. We managed to get around 400 members of the public into a working maximum-security prison for the show.” During the exhibition, the public were confronted with the material conditions of the prison, and invited to celebrate his work alongside that of the prisoners from the workshops, in the environment the photographs derived from.

"The exhibition was in Mandela’s old cell. We managed to get around 400 members of the public into a working maximum security prison for the show."

- Mikhael Subotzky

Another set of images from Pollsmoor which leave an impression are captioned ‘Cell 33 E2 Section (1)’ and ‘Cell 33 E2 Section (3)’ (2005). In these photographs, there is an overbearing sense of claustrophobia. The viewer is struck by a sense of collective entrapment, the similarity of the prisoners’ steely expressions. In this image, the viewer is given an immediate, visual window into the extent that South Africa imprisons its citizens. The image is a fitting illustration of the country’s incarceration rates, which are the second-highest in the world per capita, after the United States: “Firstly because of the history of racism during apartheid,” Subotzky offers, “and secondly, as far back as the British colonial government, those in power have actively created a criminal underclass as a means to steal land from its rightful owners”.

"As far back as the British colonial government, those in power have actively created a criminal underclass as a means to steal land from its rightful owners"

- Mikhael Subotzky

In this socio-political climate, it would be easy for the photographer to have solely focus on the physical conditions of the prisons when making this project (which spanned 2004-06), or to contribute to the narratives on prison gang cultures which are often reported in the mainstream press. Subotzky mentions the notorious Numbers gang, for instance. Yet for him, these stories were ‘clichés’. “We have big prison gangs in South Africa” he explains “with their tattoos and mythological history. I stayed away from that because I was wary of exoticizing those stories and images. So I focused on overcrowding, everyday life – prisons as a home to these people”. In this comment, Subotzky’s intentions are laid bare: to not perpetuate the simplistic narratives about prison, and replace them with images that reflect a reality that is both nuanced and visceral.

Representation, for some creative practitioners, is a form of activism, an act which can challenge dominant imagery and question authoritative depictions of prisoners. In the Die Vier Hoeke series, we learn not just the physical reality in South Africa, but also the photographer’s impetus, drive and passion to subvert the power of imagery. “I wanted to find ways to critique photographic representations,” Subotzky explains, “but still being brave enough to make them. It is an interesting tightrope walk”.

The camera is a mechanism – Subotzky proves – that can reveal that which is hidden from view. But it also can create a sense of physical distance, and does not protect the photographer from absorbing the emotional burdens of being captured: “I did have a form of PTSD in relation to some of the things I witnessed,” Subotzky explains. It is clear that at the heart of the series there is an unwavering commitment to documenting the material conditions and lived realities of prisoners, of submerging oneself in their environments.

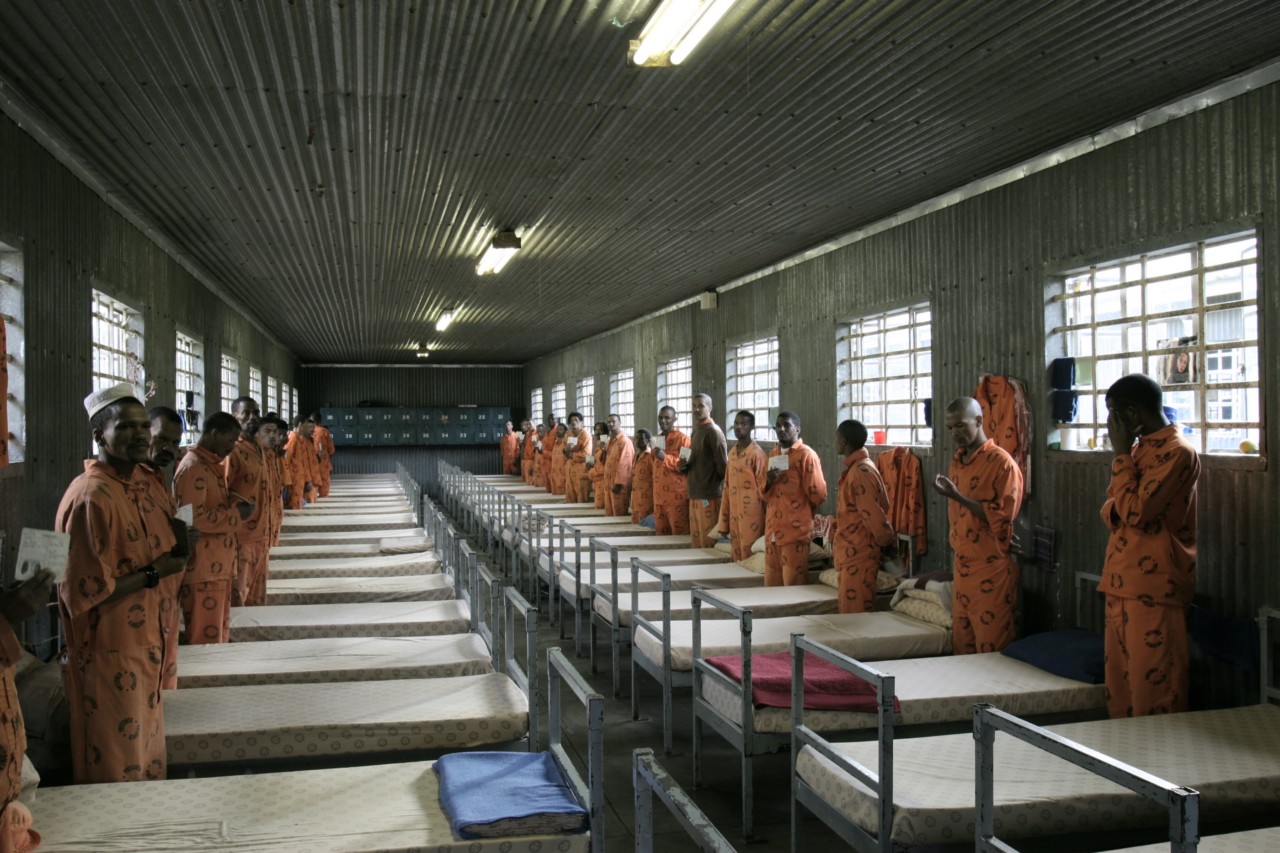

In 2004, Subotzky was reading Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish: the Birth of the Prison (1975), to understand the socio-economic and political context which has created the modern penal system since its creation in the early twentieth century. Foucault writes, “surveillance is permanent in its effects, even if it is discontinuous in its action”. For Foucault, the theory of punishment is predicated on the idea of rendering inmates invisible to wider society. To be surveyed is to be disciplined, an ideology made visually apparent in the photograph ‘Voorberg Prison Porteville, South Africa’ (2004). Surveillance is portrayed here by the regimented, repetitive stance of the prisoners – all lined up by their beds, dressed in identical orange jumpsuits. Individuality and agency are stripped. The role of the camera as an active observer, Subotzky demonstrates, allows it to communicate the disciplinary acts of prison, however uncomfortable. “Later, as my practice developed, I reframed a number of these images in relation to the gaze and my discomfort, in a work called I Was Looking Back,” he explains, “to rethink them according to my own discomfort and ambivalence around photography and representation”.

There is a timeless quality to the Die Vier Hoeke series; the project is an interpretation of history which holds political and ethical weight in the present. In a commitment to the notion of lived experience and shared human feeling, Subotzky embarks upon the difficult task of representation with the veracity it deserves, subtly documenting the complex ethical terrain the South African prison system presents to anyone who enters, or indeed views it from afar.