Winter: A Season of Visual Contrasts

Rosalind Jana explores the "line between warmth and cold, between light and dark, between ease and perseverance" through the work of Magnum photographers

Photographed out in the snow, a person can look more like a matchstick: a spindly outline thrown into relief against the white gloom. A thick layer of fog might do similar, or an especially vast expanse of overcast sky. All it takes is anything that muffles the landscape, rendering it pale enough that, in its bid for the right exposure, the camera will reduce everything else that populates the frame to mere silhouettes.

This phenomenon is especially visible in Leonard Freed’s 1964 photo series of winter in Holland. One image sees a number of ice-skaters becoming less and less distinct the further back in the mist they linger. In another where sunshine sweeps low over the scene, those on the ice cast long shadows across a huge gaggle of birds in the foreground.

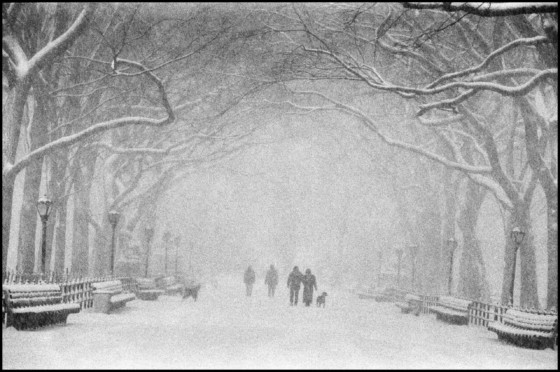

These contrasts occur elsewhere too. Nikos Economopoulos’ photo in Eastern Anatolia suggests a visual kinship between a single bare tree and the four men with hands stuck deep in their pockets clustered by the water’s edge. Burt Glinn’s 1963 photo in the USSR does similar, albeit more crisply: the dark shape of a woman in motion contrasting with the militant (and slightly rickety) rows of fences around her. In Bruce Davidson’s snapshot of poet’s walk in New York’s Central Park, human and animal alike become dark blots beneath the snow-coated branches. In Josef Koudelka’s photo taken during an Albanian blizzard the only defined shapes are the thin wires and apparatus of telegraph poles, and a single figure with one hand raised to his head as he battles forward. Even Inge Morath’s photos of Moscow, bright as they are, often dwell on black jacketed passersby, their outlines more like cut-outs against the vivid colours and contours of the buildings behind them.

"Looking at these photos from the warmth of one’s own home provokes a curious feeling. In their lack of distinctive features, many of these figures blend into their landscapes, becoming, as it were, almost natural phenomena, just like the trunks and poles and fences around them"

-

Looking at these photos from the warmth of one’s own home provokes a curious feeling. In their lack of distinctive features, many of these figures blend into their landscapes, becoming, as it were, almost natural phenomena, just like the trunks and poles and fences around them. But they simultaneously arouse a very human recognition. In their anonymity, these images could be of any of us. They invite identification, reminding us of exactly what it feels like to hear the compact crunch of snow underfoot or to round one’s shoulders against a murky morning. Much like a good line of poetry – Sylvia Plath’s ‘Winter Trees’, for instance, where “wet dawn inks are doing their blue dissolve,” or Frances Horovitz’s ‘New Year Snow’ with its image of “a bowl of dull quartz for sky” – they conjure the knowable world anew, making it feel somehow close at hand.

All seasons bring with them their own set of images, conditions and kinds of light – each, in their own way, evocative, especially when viewed in photographic form. Late summer evenings where the sun seems reluctant to go, leaving a vague orange glow in the sky long after departing. The cold, fresh vigour of white clouds racing overhead in spring. I can’t speak to the seasons globally here. The year round calendar of weather is a very different thing in Britain to, say, Australia. But in the parts of the world where winter remains synonymous with cold, rain and snow (actual or now, often, futilely wished for), such considerations of temperature and light often become ones of real contrast. Unlike those hotter months, come winter a significant visual distinction emerges between indoor and outdoor. To further render it in simplistic terms, one might say that it becomes a line between warmth and cold, between light and dark, between ease and perseverance.

It is a line that neatly divides many of the wintery images in Magnum’s archives, too. On the one hand there is that vast world beyond the front door: ghostly forests, frozen waterfalls, Nordic islands, scrawny park railings swallowed by mist, waves frothing over cold shingle, Venice looking melancholy under grey skies, damp Welsh streets after dark. Some of these images are unpeopled, suggesting a world that renews itself year on year, shedding its leaves and standing stoic through the elements until the ground thaws out once more. Others, as explored above, let the photograph’s inhabitants remain as silhouettes, or hint at humans tucked away elsewhere: their presence indicated in car tail-lights and windows where the glow spills out around closed curtains.

Many images, too, dwell more fully on those out in the elements, whether the focus is on a delivery man hefting two hog carcasses over one shoulder in Chinatown while snow drifts down, yellow jacketed commuters on a chilly metro platform, Japanese families fishing for shimiji clams in minus eighteen degrees, or, as in Hiroji Kubota’s striking 1982 photo from Inner Mongolia, two young boys in warm coats, each perched on a magnificent camel decked out in its thick winter fur.

In these photos one is reminded keenly of the sensation of being cold: the clothes it requires, the postures it provokes, the biting exhilaration and numb extremities it offers, the relief found in retreating afterwards to the welcome embrace of central heating or lit fires. These contrasts work in reverse too. Photos of indoor life take on a particular hue in winter, set against the knowledge of the weather beyond the windows. Not that they are always automatically cosy. Chris Steele-Perkins’ photo of a pensioner by a fire seems somehow colder as an image than any equivalent ones outdoors featuring roaring braziers or golden steam rising from street vendor’s stoves.

Others, however, yield the intimacies and comforts of a winter’s day kept at bay. Christmas dinners and tree decorating illustrate the conviviality of people drawn together with a common purpose when the days are at their shortest and darkest: united in celebrations marked by ritual, light, and lovingly prepared food. Rowdy images of punters in pubs socialising or singing evoke the muggy heat of windows steamed up by body heat and trapped breath.

"It is the window that perhaps proves the best portal for winter’s many contrasts. A natural friend to the photographer – what better than a frame within a frame?"

-

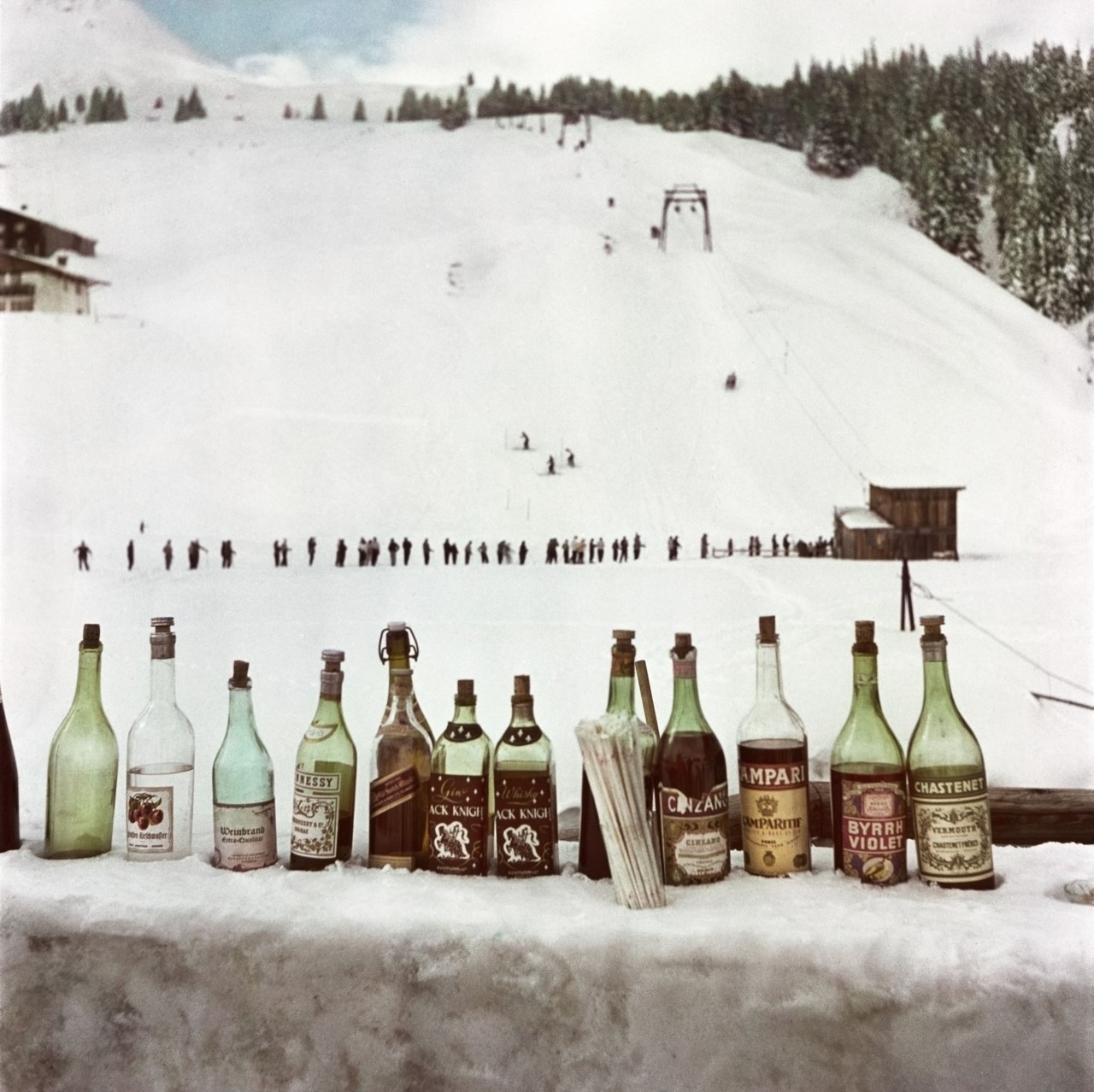

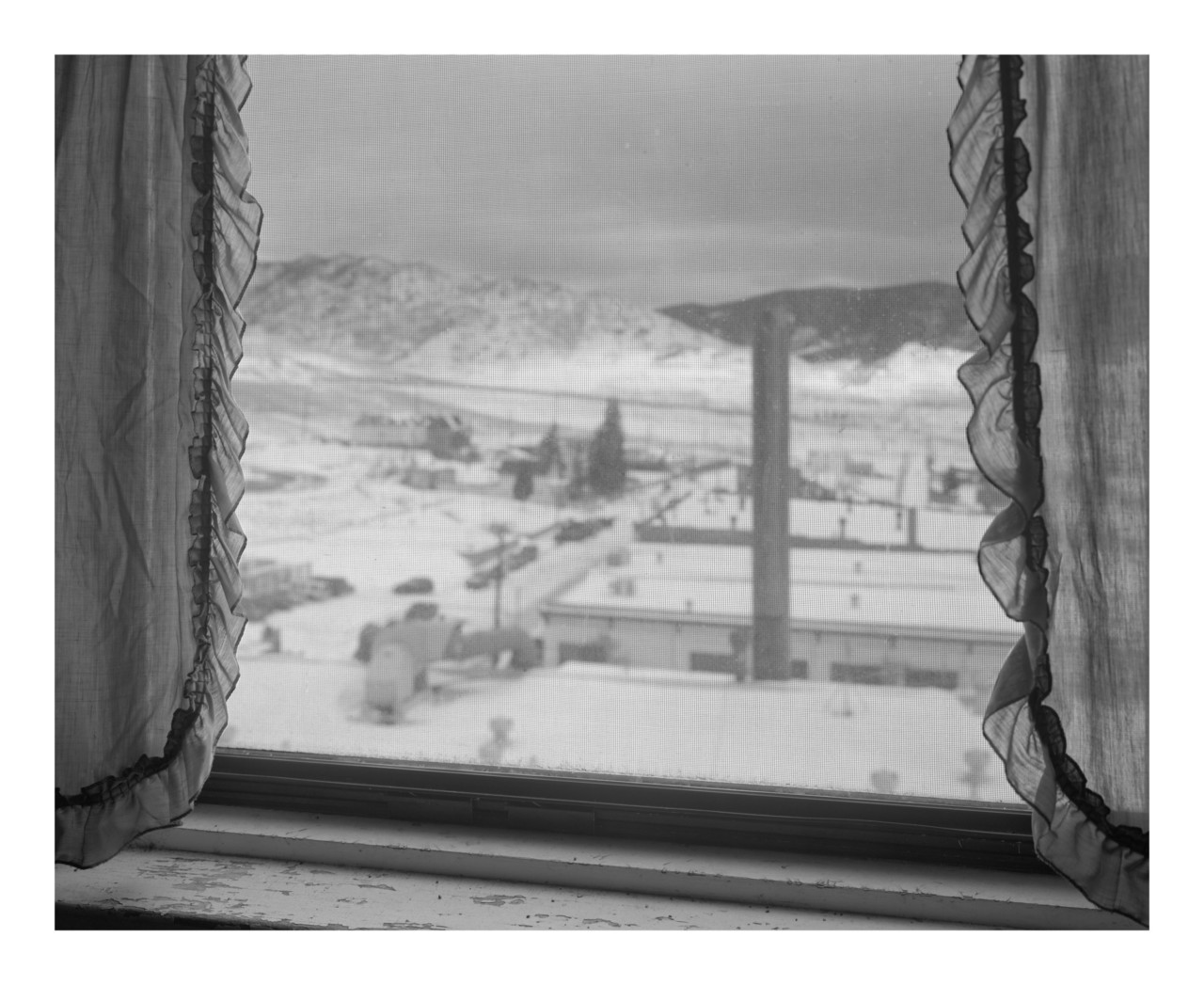

It is the window that perhaps proves the best portal for winter’s many contrasts. A natural friend to the photographer – what better than a frame within a frame? – Magnum’s archives yield a number of images that allow for simultaneity of place. Whether the camera is on outside looking in or the inside looking out, we as viewers are given a kind of precious double vision. In Jean Gaumy’s photos taken on polar yacht Le Vagabond, the icy blue Arctic surrounds a small, saturated square of light: the yacht’s inhabitants pictured safe and warm in the heart of an inhospitable environment. In Ferdinando Scianna’s observations of a New York bar on a winter’s evening, captured from the street outside, the neon signs and stacked bottles are partly blurred by the condensation running down the glass. Other images provide the reverse, dwelling on girls watching snowball fights from bus windows and winter vistas edged by thin, frilled curtains. Occasionally the divide dissolves entirely: glass doing the work of a double exposure, overlaying faces and artificial yellow lights on the scene on the other side of the window, inner and outer fused as one.

In one way or another though, all these images are windows. Whether dwelling on matchstick figures sledging down slopes and trudging through storms, capturing the gaiety of a festive party in full swing, or pausing at the Edward Hopper-esque sight of a luridly lit restaurant on a bitter December night, such photos are their own kind of fleeting glimpses into other worlds: full of blizzards and shadows, elaborate feasts and faces lit by candlelight, all equally able to be enjoyed from the safety of a laptop in a snug bed or a phone scrutinized on the train, a thousand other winters crowding close on the screen.