The Parameters of Our Cage

Alec Soth and a Minnesota prisoner exchange ideas on art, life and justice in a new book

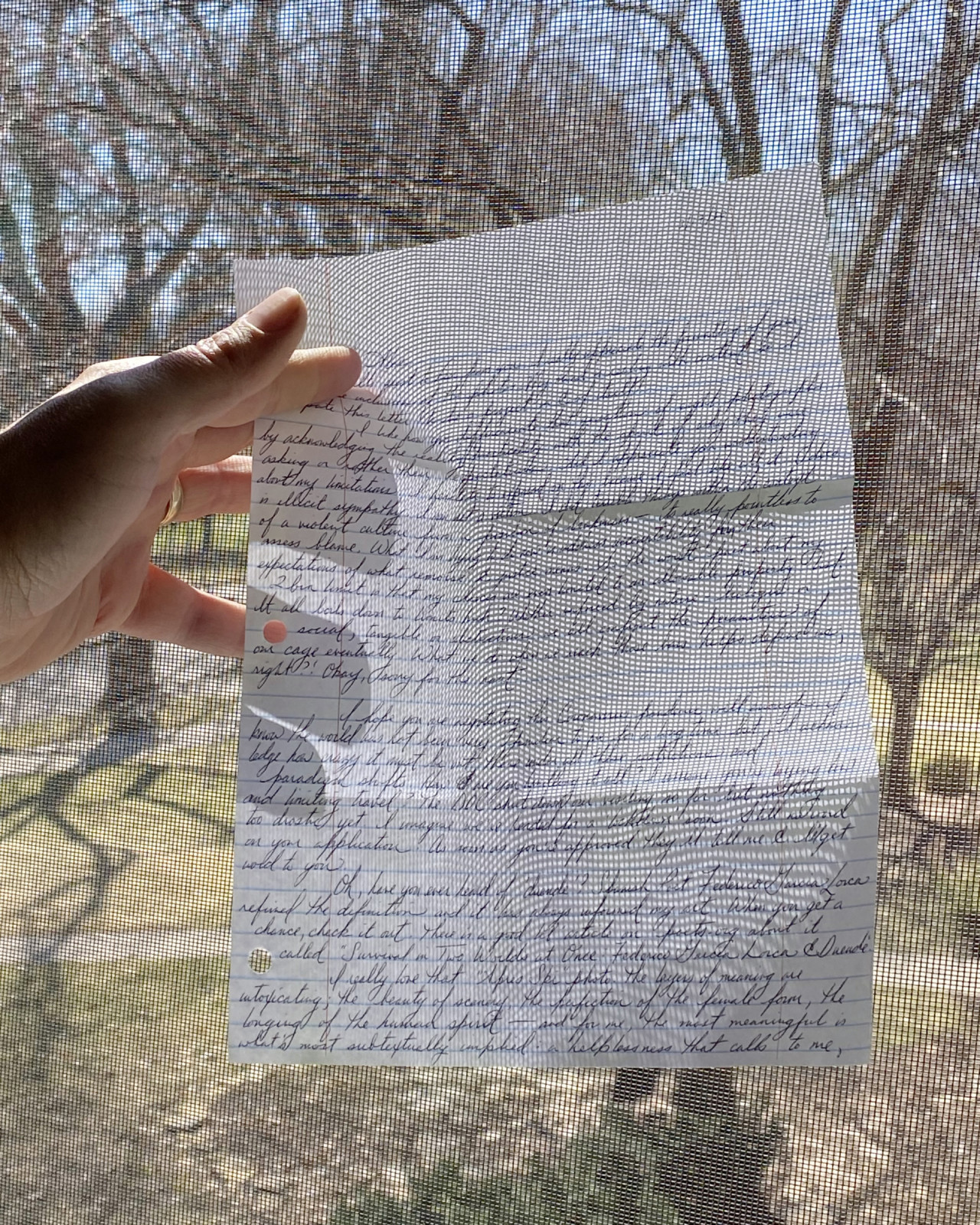

In January 2020, Alec Soth received a letter from the Minnesota Correctional Facility in Rush City. The letter came from Christopher Fausto Cabrera, an inmate at the prison, and self-taught writer and artist. A nine-month long correspondence between the two followed suit, which forms a new book titled The Parameters of Our Cage, released by MACK.

Continuing through the events of the summer, from antiracist uprisings to the impacts of Covid-19, the letters traverse feelings of rage and loneliness, as well as optimism. Over the course of their dialogue, the two artists contemplate the fallacy of justice in America, discuss creativity as a means of escape, and speculate on the eight photographs that each artist would bring with them to a desert island — one of which, depicting Cabrera’s family, was recreated by Soth in real life.

Soth has been collecting vernacular photography, including in the form of family photo albums, for a number of years. Below, we share a letter from the book, by Cabrera, in which he reacts to a prompt by Soth, and contemplates family photographs — of strangers — from this collection.

Copies of The Parameters of Our Cage are available on the Magnum Shop here.

April 25, 2020

…

So I came up with a creative exercise. My idea is to send you some snapshots I found. I’d like you to choose one or more and write about them individually. Think of the photograph as a diving board and then jump into a pool of thoughts.

Thanks, my friend…

Alec

May 5, 2020

Dear Alec,

Happy May to you my friend! I hope you are surrounded by love & creative verve.

One of the pictures you sent got denied because of “gang signs”? I appealed the decision, although I’m not confident in any oversight. They’ve denied babies holding their hands at odd angles as gang signs. Even if it is a “gang sign”, who cares!? How is that a threat to security?

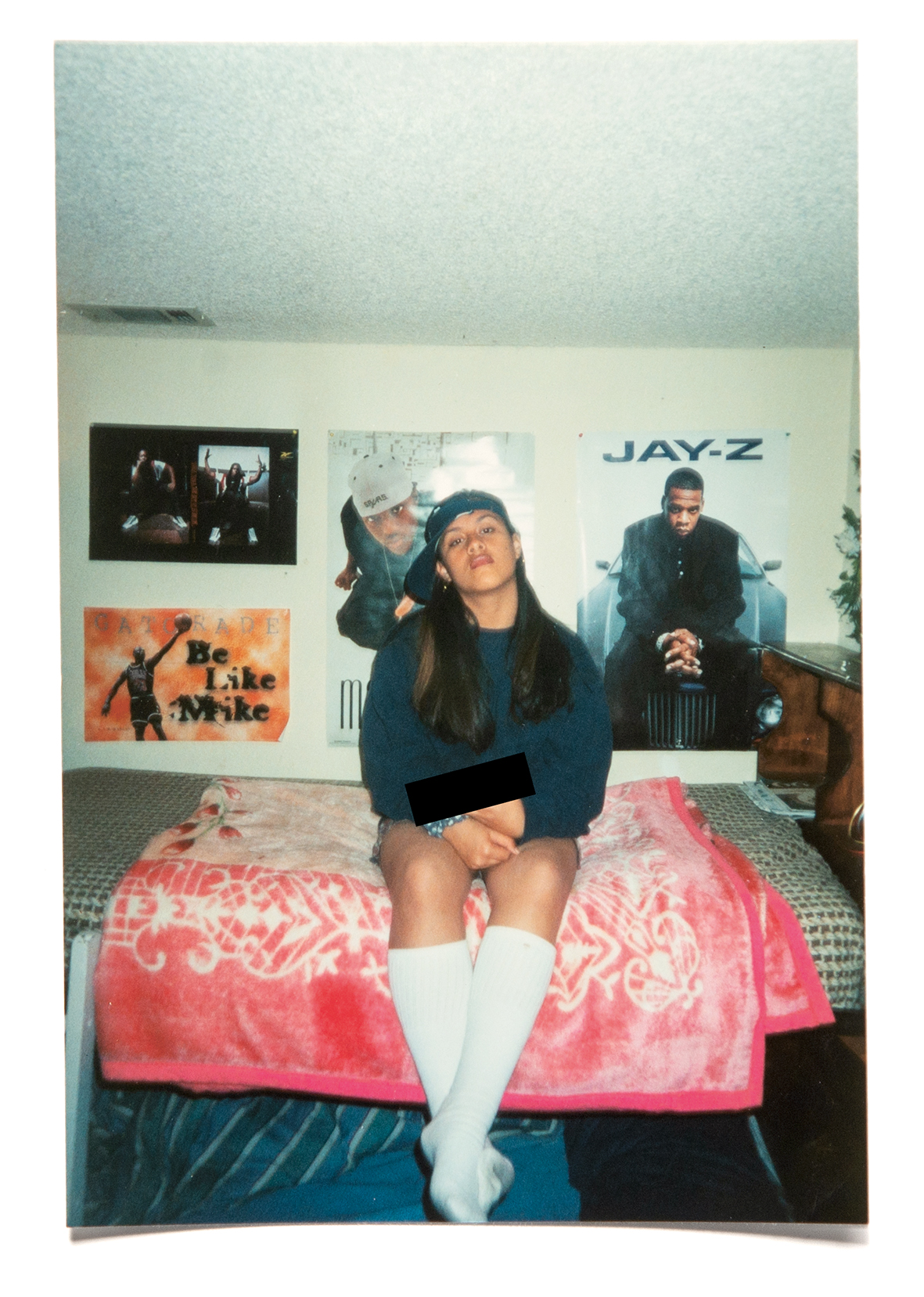

My initial response to these found snapshots was to breeze through and disregard them as belonging to others. It wasn’t noble, like out of respect for their privacy. Rather like an absence of desire to see anyone outside of my own sphere. What’s the value of personal photos unless you know the people within them? – I thought initially.

My aunt Kathy was just telling me about how she was sifting through her cardboard box of old photos and found some of me as a child. This prompted a few memories, but without seeing the specific photos I felt a bit dissociated to this inheritance coming from a box I had yet to sort. If I were to pick up a handful of photos from my family’s box, each one would be electrified by bias, saturated in complicated emotion. It made me think about what you said about your aversion to taking personal pictures and the value of the distance between you and your subjects.

Thinking about that, I went through the snapshots you sent again and felt myself pulled closer. Maybe the relative distance allowed me to confront my story a little less tainted? Like when a painting has become overwhelmed with attention or an essay is too fresh with emotion. Our relationship with the past is too personal, so we put it in a box and ask time to intervene. It’s interesting to enter the past by the backdoor of other people’s photos.

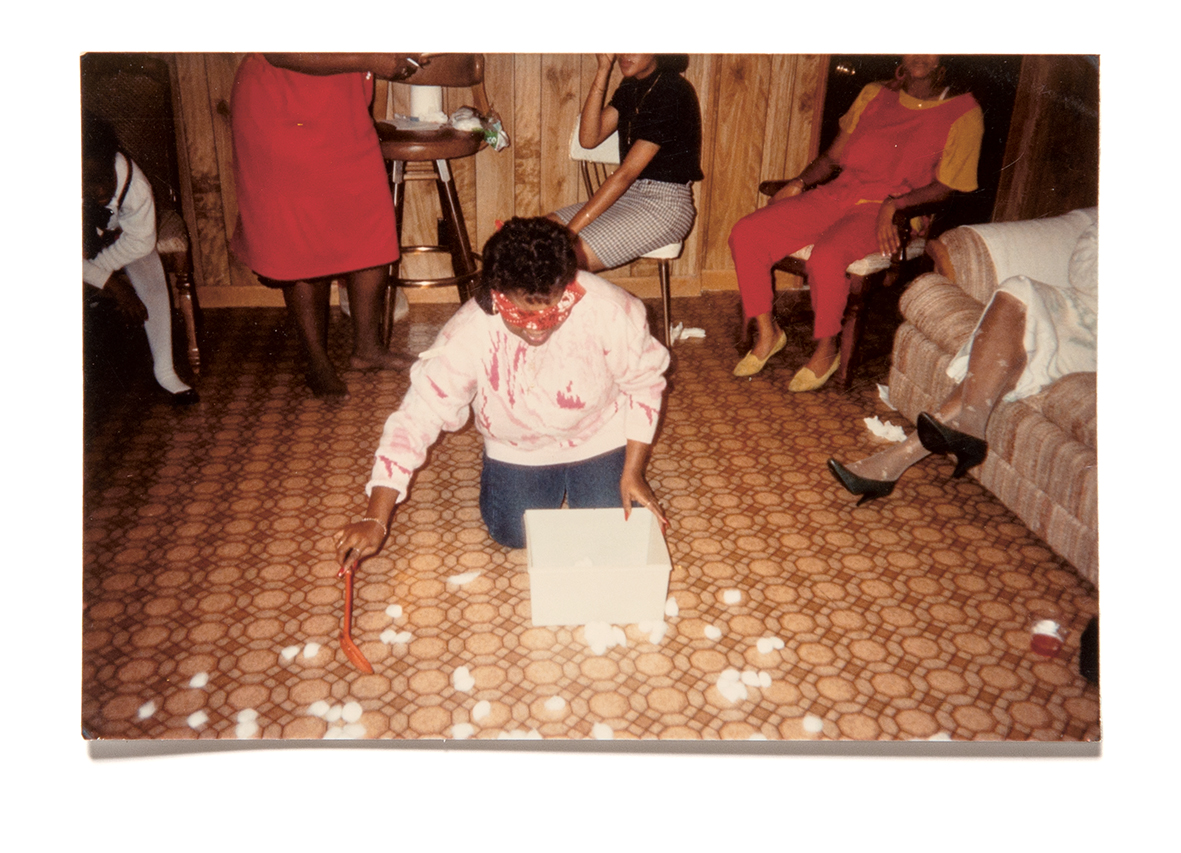

Is the emotional connection to innocence lost forever at a certain point? Is this what nostalgia means? When we look at these types of photos is it possible to truly occupy dual points on our timeline and reclaim some innocence? We may not be able to reject cynicism, but can we choose to block some of the bitterness that’s calcified our spirit to regain some of the carelessness of childhood? I see it in this snapshot, a suspension of disbelief that makes our approach to life like watching a magic trick: you must buy into the illusion in order to be swept up in the wonderment. Surrounded by family, she’s blindfolded and playing some sort of absurd game, buying into the fun. Anonymously outside the frame those around her toggle through a gamut of perspectives seen through their posture: the kid at the top left corner leans on elbows anxiously at the edge ready to do something, the older lady next to her, barefoot and about to strike up a cigarette, seems to be managing the issues of the younger one who is seemingly exhausted in her own drama, while the girl in red sits fully in the chair, her body making contact at every point, on the precipice of her adulthood, and the lady on the couch with her legs crossed enjoys the show from a seasoned age.

How long has it been since I was willing to play the fool and abandon my seriousness? To shed my petty misgivings, put the blindfold on and get on my hands and knees in a position to be laughed at by people who’ve known me all my life? The time will arrive for her soon where she will discover things about her family she never knew, things that will change the way she may think about them. She’ll start making her own adult decisions that will sacrifice degrees of her innocence and complicate the relationships that ripple around her.

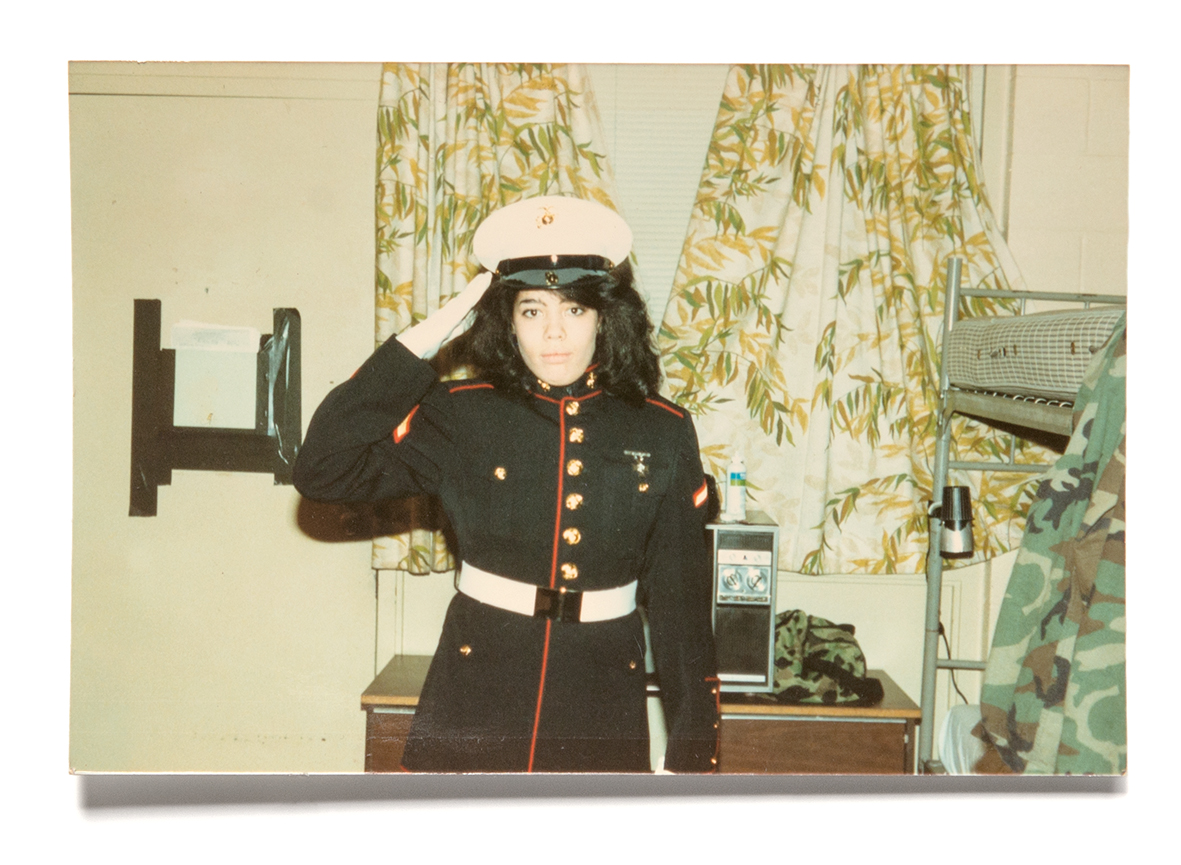

When was the last time I bought into the magic of life? Without looking for the strings, calling out flaws and faults or filling the air with my cynicism? What’s the big deal with putting on that blindfold and playing the fool? I’m so afraid of being taken for a fool. I’ve forgotten how good it feels to let go. I contemplated enlisting after high school. I vividly recall sitting in my truck as my big cousin talked me out of it. “You’d be pimpin’ yourself out to the government,” he said, “they don’t give a fuck about us.” Although I was selling him crack at the time, I felt he made a good point. Since my uncles were tax-evading construction workers, my cousins used and sold drugs, my mom smoked weed and used to hang around Cubans who personified Tony Montana from Scarface, I never considered the system ever to have our best interests in mind. To become a cop or join the military would’ve been an intentional deviation and be considered a betrayal. We saw ourselves as untrained soldiers in the streets fighting for our American Dream of money, power and respect.

It’s all part of buying into that same illusion of a childhood magic trick. Despite the details of allegiance, culture or environment, the base mold of a person capable of using violence against another for whatever reason is similar. Every soldier has their justifications. The police feel entitled because their violence is sanctioned and they operate with immunity, even when they kill unarmed people. The military goes into foreign countries with a license to kill because politicians gave them permission. I grew up believing I had a right to defend myself and didn’t ask for permission because I wasn’t the only one with a gun on the streets.

The question becomes how we view the righteousness of the purpose. I’m not trying to justify violence or discredit law or military enforcement; I’m merely looking for solidarity with this soldier.

When I was young, life was a river I was barreled down in a boat I didn’t buy, with people I didn’t choose, seeing banks I didn’t feel I had access to. I wonder about people who are born into law enforcement or military families or soldiers across continents who are birthed in warzones. Aren’t they operating from similar ideologies? Isn’t the spirit of the things we do more universal and not as black and white as a right or wrong based on a government’s permission?

I know we got a few irons in the fire, but I meant to ask you more about the enlightenment you experienced on that beach. I’ve been struggling with depression my whole life and have recently felt more at peace than ever before. Do you think art, purpose, and maybe fine-tuning craft could somehow help to re-wire our brains and turn these shadowed elements into a function as opposed to seeing them as an illness or dysfunction? I can’t even imagine who I’d be without my ability to see in my dark — all the beauty I’ve discovered!

Okay my friend, stay enveloped in love & blessings. I am so thankful for you.

With Love,

Fausto