Photographing Syria’s Civil War and its Ramifications

Emin Özmen reflects on a near-decade of work spanning the war’s early phases, the growth and fracturing of militias and militant groups, and the ensuing refugee crisis

The following article conrtains images of violence and injury that some readers may find distressing.

Ten years old this month, the ongoing Syrian conflict started in March of 2011 and has ebbed and sprawled since. It has drawn in other nations, not least Russia, the United States, and Turkey. It has gone from a global media obsession to a now oft-forgotten war, international outrage and obsession giving way largely to news fatigue. The war spawned the Islamic State (IS), both as a player in global terror exporting some of the war’s horrors around the world and as a short-lived geographical caliphate. The conflict has also created the largest refugee crisis of recent history – with more than 6.6 million Syrians leaving the country and another 6 million displaced within it, according to the UN Refugee Agency.

Emin Özmen has, since 2012, been photographing the fighting within Syria, and the ensuing humanitarian crisis, in the paired projects Revenge and Limbo. Here he reflects upon his work in the country, the changing nature of the conflict, the difficulty of witnessing and documenting inhumanity, depletion of hope, and the prevailing importance of recording the horrors of war.

Can you explain how you came to first work in Syria – and how its closeness to Turkey impacted your decision to make work there – physically or emotionally?

From the beginning of the conflict, I had followed everything that was happening through the news. In 2012, one year after the beginning of the conflict, the fighting was at the gates of Turkey. Aleppo (which is 60 km from the Turkish border) suffered heavy aerial bombardments in June. This tragedy was taking place at the doors of my country, only an hour away; I felt really concerned and upset by it. I thought about it all the time.

Because of the nature of my job – as a photographer – and knowing that a war was raging so close to my home, I couldn’t just sit by idly. So, I decided to cross the border – to witness and document what was happening.

"I have lost faith in many things, but I still think that documenting conflicts is essential for history, for collective memory. It’s essential that we don't forget what happened"

- Emin Özmen

What was your ‘mission’ for the work when you started, and how has it changed over time, if indeed it has?

A year before the start of the Syrian conflict, my documentation of the drought in East Africa had attracted a lot of attention in my country following the publication of my photos in the leading Turkish national newspaper, where I was working as a staff photographer at that time.

The newspaper collaborated with the Turkish Red Crescent Society in an aid campaign that raised several million dollars and I continued to work in Somalia for a year. I could see how this aid had a real and positive impact on people, at least in the short term. I was at the very beginning of my career, only 26 years old, and seeing this was a great motivation for me. I naively thought that being a photojournalist could help people: that was the reason why I was doing photography.

In 2012, following this positive experience, and being deeply concerned about what was happening in Syria, I hoped that maybe, thanks to my photographs, I could provoke a reaction and change something there.

Today, with hindsight, and after ten years of this bloody war, in which hundreds of thousands of people have lost their lives, I have lost all hope of changing things through photography. I have come out of this conflict traumatized. I have lost faith in many things, but I still think that documenting conflicts is essential for history, for collective memory. It’s essential that we don’t forget what happened.

"Each time I went to Syria, I discovered new flags; I heard the names of new groups. Then, these groups started fighting among themselves to keep control. It was no longer the struggle of the Syrian people"

- Emin Özmen

You witnessed firsthand the changing face of the conflict – particularly the changing nature of the rebels, with the increasing presence of radicals and foreign fighters in Syria. How did this change the practicalities of working there?

Every time I crossed the border, I learned of the deaths of people I had met before, on previous visits. Maybe the shelter where they had been staying in was no longer there, or the whole neighborhood was destroyed. More and more civilians were arming themselves and becoming combatants. In 2013, I felt that the conflict was dragging on and radical groups began to develop. They offered salaries for fighters, and many people joined them. In most of these cases, I felt that this was more a means of survival than a matter of conviction.

Each time I went to Syria, I discovered new flags; I heard the names of new groups. Then, these groups started fighting among themselves to keep control. It was no longer the struggle of the Syrian people.

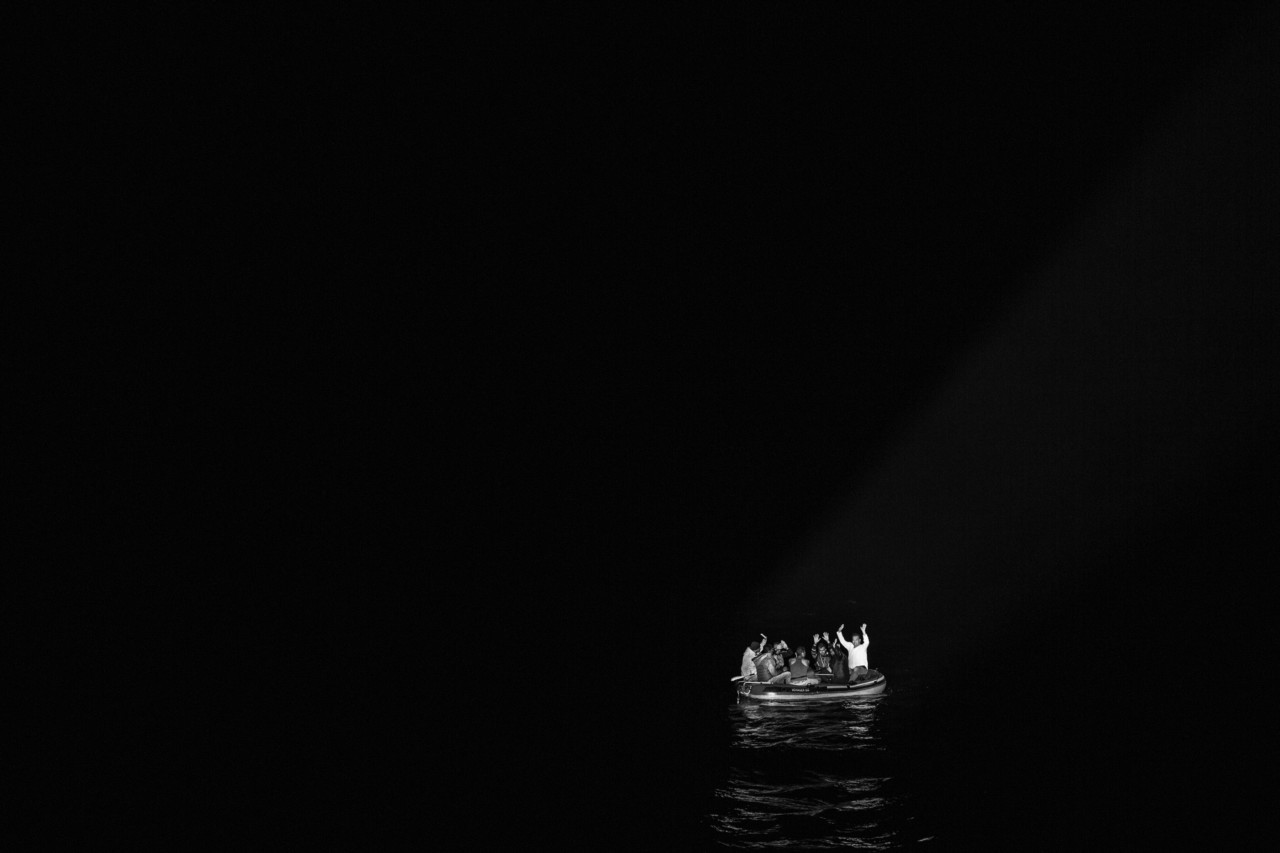

Confronted with the extreme violence of these groups, I decided to stop going to Syria for a while. I started my Limbo work documenting civilians fleeing conflict in Turkey and Europe. I returned to Syria again in 2015.

"Nothing is worse than living in denial of suffering, injustice, crime. We, as human beings, must be able to face up to what we are capable of doing to our peers and learn from it, in order to build a better world"

- Emin Özmen

You witnessed and documented brutal scenes including torture and executions, as well as fighting. You saw the early days of IS’ activities – did you experience a dilemma of sorts in photographing these events? How important is it or was it to show this aspect of the war to those outside the country?

What happened there was wrong; I witnessed things I’ve been trying to forget ever since. Interrogations, torture, and even executions: I found myself in a kind of whirlwind where I didn’t have time to think. I acted guided by my reflexes and survival instincts. At the time, some photos were criticized they presented a bad image of the opposition. But I was there with responsibilities. I didn’t want to hide or manipulate the things I saw. All of it had to be documented and seen. But I was recording violence that no one wanted to see. At that time, only the forces of Bashar al-Assad were supposed to act in a barbaric and condemnable way. But a war is a war. The mechanisms are extremely complex. Unfortunately, the aftermath of the conflict demonstrated this.

I often think back to the photos of the Second World War and, especially, those who bore witness to the Holocaust. Without these extremely shocking photos, maybe nobody would have believed what happened. Nothing is worse than living in denial of suffering, injustice, crime. We, as human beings, must be able to face up to what we are capable of doing to our peers and learn from it, in order to build a better world. Even if I am not very optimistic about that myself.

"I think one can see that as more years went by I wanted less and less to document the violent, military aspects of the conflict: I was too traumatized. I turned my attention to the impact this conflict was having on civilians"

- Emin Özmen

How have you seen your own work and your approach change over the ten years of working in Syria? Do you think you can see for yourself this change in your images?

I think one can see that as more years went by I wanted less and less to document the violent, military aspects of the conflict: I was too traumatized.

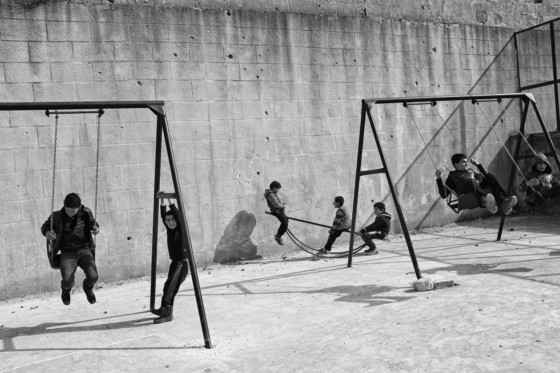

I turned my attention to the impact this conflict was having on civilians. That’s how I started ‘Limbo’. I think this evolution is visible in the work. The Limbo work is much less “raw” than earlier images of the fighting, it’s more subtle. Documenting this conflict has had a huge impact on the way I photograph now. I now try to “say” the same things, but in a less graphic way.

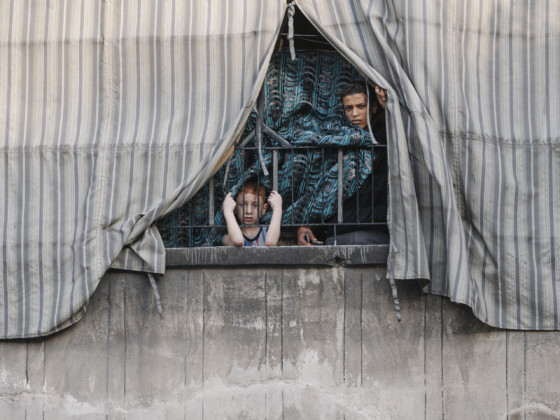

After witnessing the violence suffered by Syrian civilians, many of whom were forced to become “refugees,” it became important for me to document their fate. I tried to collect their stories and capture their experiences and feelings in a soft or sensitive way. It was in total opposition to the violence of my first images of the conflict.

The lives of all these people, their stories, their destinies, were suspended in a state of “in-between” where expectation, hope, anxiety, confusion and anguish coexisted, collided, confining them to lives lived in a vague and confused state. The visual language I used to try and reflect this situation had to mirror these emotions. These later images are the antithesis of my photographs of the fighting.

My heart is broken by what I saw in Syria. I am aware of being deeply traumatized by it, but I am trying to heal, slowly, particularly through photography, which may seem paradoxical.

Ultimately, being a photojournalist is still a profession that I chose. Civilians suffering from conflict didn’t choose any of this.

"I would say that photographing the refugee crisis was an important emotional challenge, but that sometimes hope comes to me from that work, contrary to how I felt when I photographed the fighting in Syria"

- Emin Özmen

Covering the refugee crisis – did this resonate with you more on an emotional level than your coverage of the fighting itself? Which did you find the more challenging, and which the more rewarding?

I would say that photographing the refugee crisis was an important emotional challenge, but that sometimes hope comes to me from that work, contrary to how I felt when I photographed the fighting in Syria.

Most people I photographed for Limbo are traumatized by the war, by the loss of their loved ones, by what they had to endure and see. It’s very difficult to listen to their stories because I feel helpless. At the same time, I have met incredible people, of a rare kindness and intelligence. I have hope for them. I tell myself that they will succeed in rebuilding a life elsewhere and I hope that they will be able to return to their country one day.

"Ultimately, being a photojournalist is still a profession that I chose. Civilians suffering from conflict didn't choose any of this"

- Emin Özmen

Looking over the work, and reflecting on your time covering Syria, does one particular event or aspect of the conflict stand out as having changed you as a photographer and journalist?

I lived through the most difficult moments of my life after having photographed the executions. I still believe it was the right thing to do, in order to collect evidence of what was going on in Syria. But witnessing this event had a strong mental impact on me. I had to face trauma afterwards. I even gave up photography for a few months, no longer wanting to touch the camera. But knowing that people live with this brutal reality every day, I can’t complain.

After these ten years – do you feel any hope for Syria? And has ten years of making work in a place that’s seen so little positive change altered your view at all of the power of media, and reporting?

I can’t really say I have hope. How do you bring back people who have lost their lives there? Thousands of children were born in this war. They grew up in violence and have known only that. Others had to flee and have already forgotten what Syria was like. My only hope is that our work could maybe help Syrians to be better understood, to create more caring for them and empathy toward them, especially by their host communities around the world.