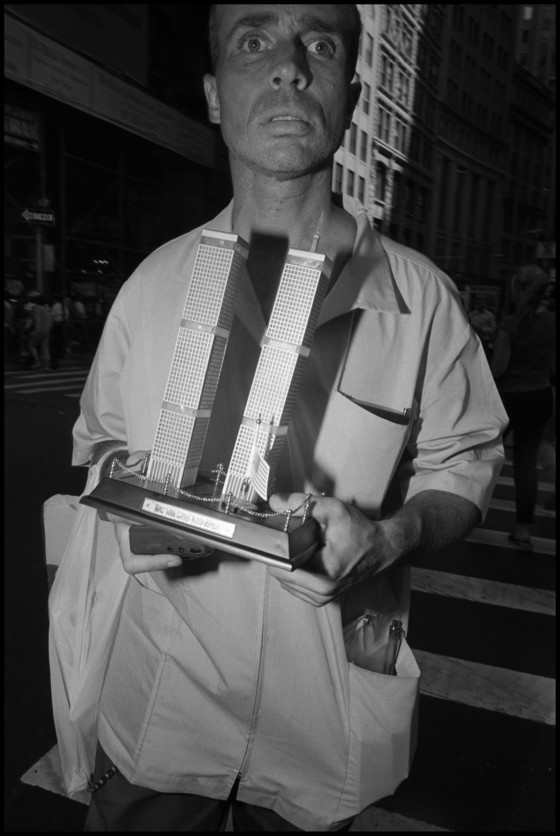

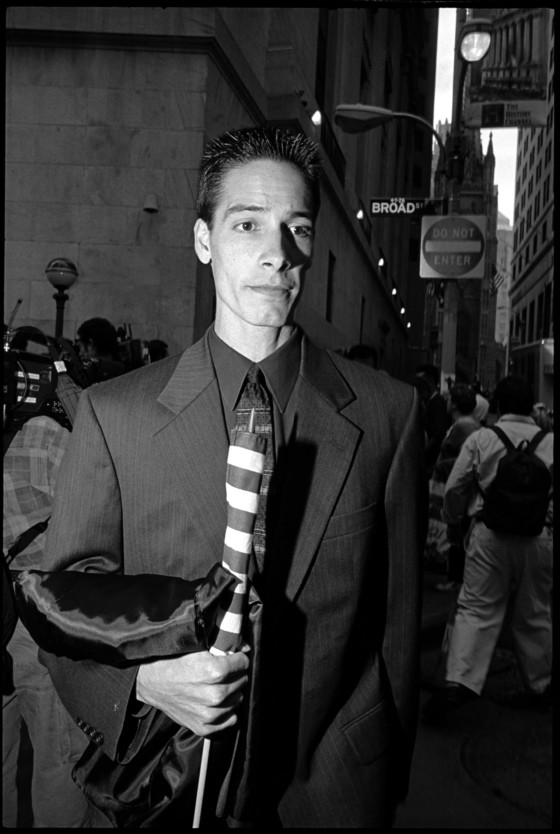

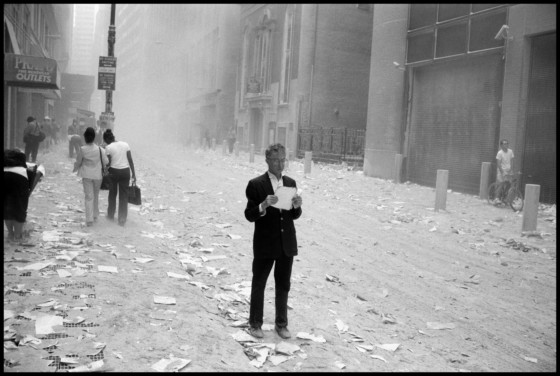

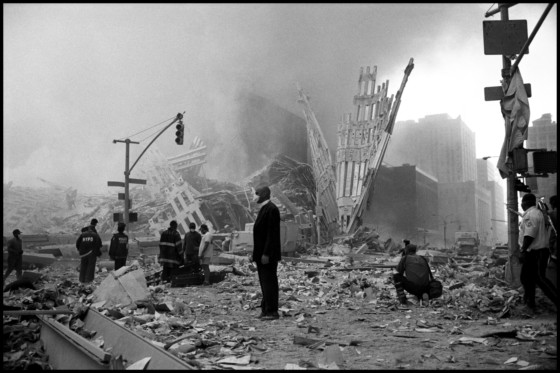

20 Years On: Remembering The 9/11 Attacks

Magnum photographers documented the immediate aftermath of September 11 and the conflict that followed across two decades

In this piece, we look back at Magnum’s archive of photography of the attacks on the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, and of America’s wars that followed in the two decades after the event. In the accompanying essay, writer and curator Julian Stallabrass discusses the impacts of trauma on photography and visual memory. His book, Killing For Show (2020, Rowman & Littlefield), explores how photography has shaped conflict post-WWII.

Read more about Magnum’s coverage of America’s foreign policies post-9/11 in this curated collection of editorial features exploring Afghanistan and Iraq here.

This article contains images of violence and injury which may be distressing to viewers.

—

The 9/11 attacks, staged at the mediated heart of empire, offered a remarkable opportunity to study the memory of traumatic events. The model of memory that emerges from recent studies of the brain has implications for the affinity of memory with still photography, the impact of iconic images as tied to highly memorable events, and the effects on memory of repetition and neglect in saturated media environments. These implications generally emphasize the power of the mainstream media to influence and alter remembered history.

Memory should be thought of as a continual reconstruction rather than a recording. Memories are not laid down once and for all but through a process of repetition and rehearsal that continually alters them. Those that are not revisited fade, sometimes to the point of disappearance, while those that are frequently visited are reinforced and transformed—‘consolidated’, as memory science has it—and become more resistant to erasure. The conditions for this consolidation process are material and may be disrupted by physical trauma, distraction, drugs and shortage of protein. Many children growing up in Iraq under economic blockade and in the even worse conditions of the Occupation were stunted mentally as well as physically by malnutrition, which will leave a baleful genetic legacy down the generations.

When a recent memory is retrieved, it is usually rich in detail and little altered by the cue that brings it back to mind. The memory of distant events is quite different, especially when it has not been much recalled. Detail is often lost, a great deal of prompting may be needed to recover it, and the properties of the retrieval cue may prominently shape what is remembered. The consolidation of revisited memories can take weeks or even years, and long-term consolidation, at the level of the entire brain system, arguably never stops, as new memories are adjusted upon each retrieval in the light of old, and vice versa.

Memory builds meaningful life narratives, which often falsely emphasize the unity of the subject across time and also edits out the unimportant so that we are not crippled by the sheer accumulation of detailed reminiscence, like Jorge Luis Borges’ character Funes the Memorious. The more alien the new material is to the conceptions built up in the old, the longer it takes to consolidate and the more likely it is to be forgotten or changed to match better with the subject’s more regular experiences and view of the world.

One type of memory appears to have particularly photographic effects. It was first described in a 1977 study by Roger Brown and James Kulik which looked at memories that seemed to preserve or freeze detailed images of shocking events over long periods of time, apparently unchanged. They interviewed adults about how they remembered such events, including the John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr., assassinations, describing the phenomenon as ‘flashbulb memories’. In these memories, episodic and source memory appear tightly melded, so that subjects vividly remember not merely the event but where and how they came to know it. Such memories also seem to have a strong affinity with the still photograph—to the extent that they were sometimes described as being like a print, static and unalterable.

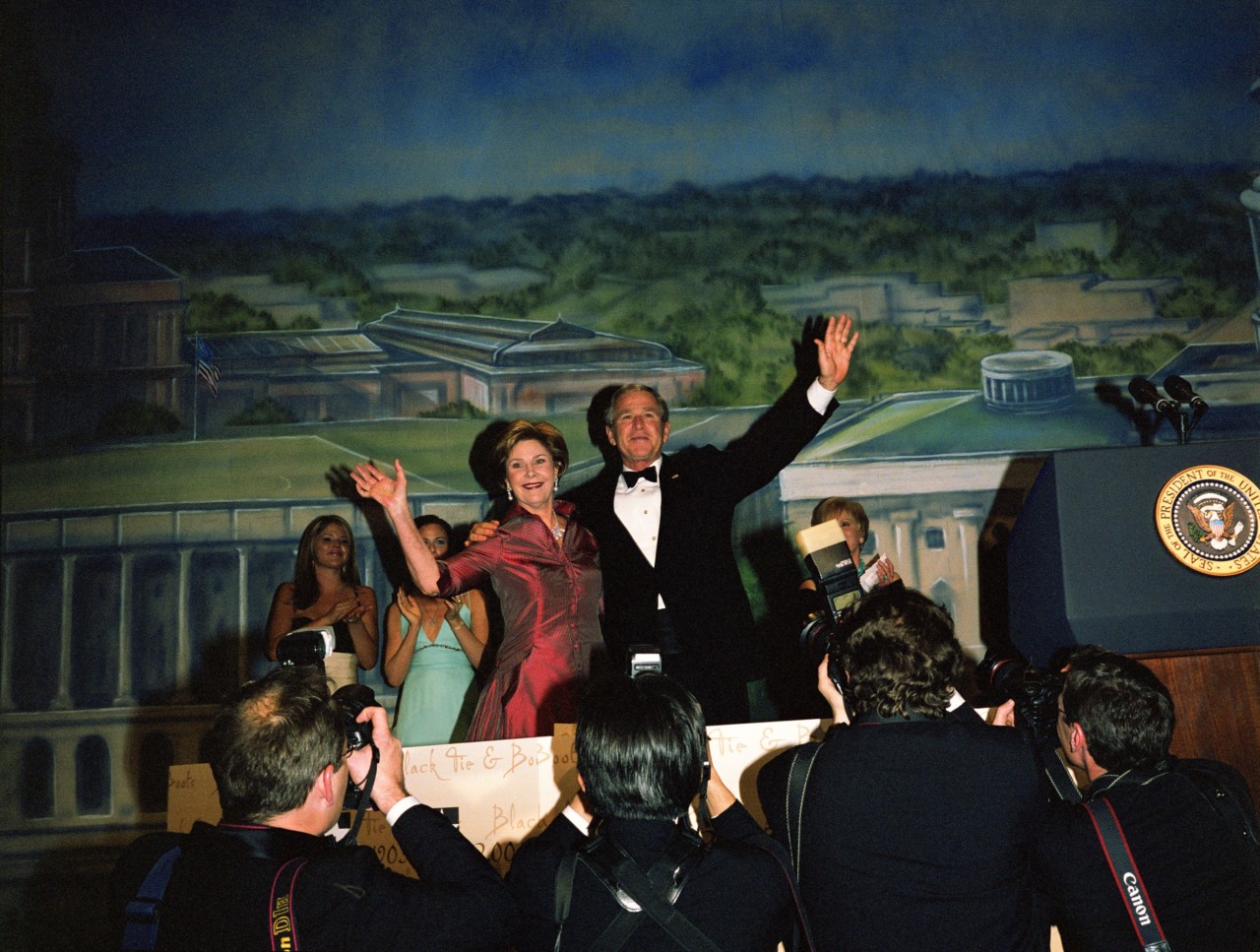

Unsurprisingly, whether flashbulb memories formed had a lot to do with the subjects’ view of the significance of the event, and this was tied to their group affiliations. Brown and Kulik’s sample was composed equally of black and white adults and showed sharp and predictable differences over how they remembered the assassination of King. Such findings have been repeated, showing that the 9/11 events are much more likely to be recalled as a flashbulb memory by US citizens than others.

There may be a link between the shock with which the disruptive icon is first grasped and flashbulb memory. Susan Sontag, in a famous passage, wrote of first seeing photographs of Bergen-Belsen and Dachau as a child, describing the experience as a deep cut that transformed her view of the world and would stay with her for life; likewise, Han Kang who dug out from her parents’ shelves a hidden album of photographs of the Gwangju massacre. Many of us have had similar experiences, and know that there are images, fused with the experience of first seeing them, that will haunt us until death.

Brown and Kulik saw flashbulb memories as fixed and accurate, but both of these qualities have been called into question by later studies. Flashbulb memories are often more persistent than others, but they do decay and fade nevertheless. While people tend to believe strongly in the truth of such vivid memories, that is no guarantee of their accuracy. For example, the Zapruder film of the John F. Kennedy assassination is what many Americans remember as if it was broadcast live or soon afterwards and was their first exposure to the news; but in fact still images from the film were first published only a week later in Life, and it was not broadcast until years afterwards. Equally, studies about the long-term flashbulb memories of the Challenger disaster show many memory errors, and no correlation between the belief in a memory’s accuracy and its actual veracity.

The flashbulb memory studies of the 9/11 events have yielded mixed results. Some show that such memories decay at the same rate as any other, while being accompanied by greater feelings of veracity. Others have shown greater durability and accuracy over long periods of time, with very few major distortions, even after several years had passed. Some memory distortions occur when different stories about the same event from various sources and times become confused (hardly surprising, given the amount of coverage), but memories of the events seem to have been laid down quickly and did not take long to consolidate. In traumatic events, high emotional arousal also seems to narrow attention on the central aspects of the matter, with the consequence that less was remembered of peripheral issues. This is similar to weapon-focusing by victims of an attack.

One reason for the strength of flashbulb memories, which ties them to the social scene, is that they are likely to be discussed frequently and compared to other people’s recollections. For those who had close, first-hand experience of the attacks, and whose memories were forged by the intense arousal of the amygdala, recollection does appear to be detailed, accurate and durable. For others, the maintenance of these memories seems to be strongly associated with collective rehearsal, narration and sharing, which can itself introduce distortions.

There is little work on the effects of media on flashbulb memory. While the enhanced and vivid memories of those who experience traumatic events through the media do fade and alter, photographs can protect them, especially when seen repeatedly, and the effect is stronger for images than for words. In more usual circumstances, the general unreliability of source memory may be compounded by a media-saturated environment in which many sources are rapidly consumed. If the repetition of orthodoxies—however mendacious—does much to consolidate them in the memory, and if the omission of alternative views, or their very rare mention, drives them from the mind, then the mass media wield considerable mnemonic sway.

Children have great difficulty remembering source information, which makes them particularly vulnerable to false recollection. Suggestive questioning is very effective at implanting false memories in preschool children, and when the suggestion is prolonged and repeated, they will recall the false memories with confidence and in rich detail. The same can be done for adults with the aid of manipulated photographs from their past or of fake political events. As the mass media erode the reliability of source memory, compounded by digital interfaces and the rapid consumption of diverse material, they threaten to make children of us all.

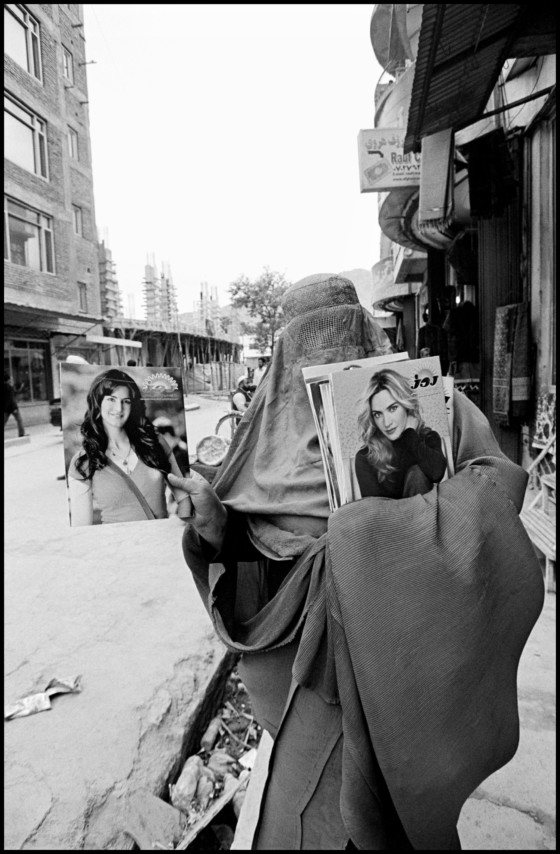

Is it any surprise, then, in our accelerated media environment that the most indigestible of the 9/11 images were banished from view—in part because of the demands of the public? Or that the towers themselves disappeared from TV screens in the years after the attacks, being deleted from pre-9/11 shows in which they had often served as establishing shots? Or even more that memories of the suffering caused in Iraq registered so little?