Understanding the Fine-Art Market: Three Fundamentals

Discover advice and guidance about working with galleries and collectors with Magnum

The gallery world has recently undergone dramatic changes, and dealers and photographers are now using new methods to reach collectors. In a series of discussions, The Complete Guide to Selling Fine Art Prints, panelists invited by Magnum will pull back the curtain on the business of fine-art prints sales, and explain how photographers can adapt to the changing market. Photographers, dealers and gallery directors will explain the fundamentals of pricing and valuing fine-art prints, what to expect (and not expect) from a gallery, and how to forge relationships with collectors. Private and institutional photo buyers will explain what, how and why they purchase.

To learn more about the seminar series ‘The Complete Guide to Selling Fine Art Prints’, please click here.

The global pandemic has rapidly accelerated changes in the way fine-art photographic prints are marketed and sold. Over the past decade, the explosion in art fairs and online marketplaces have given collectors more places to find art than ever before. Throughout those years, galleries had debated how best to use their resources to connect their photographers with collectors. The debate ended abruptly when lockdown restrictions closed in-person exhibitions. Galleries added viewing rooms or sales capabilities to their websites, and relied on newsletters and online content to stay in touch with collectors. According to a survey conducted in 2020, international galleries reported that more than a third of their sales that year were conducted online.

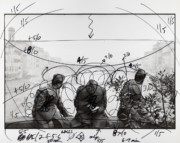

With the easing of restrictions on in-person gatherings, galleries met the pent-up craving to experience art objects in person, but they continued the digital strategies. When the new Magnum Gallery in Paris opened in October, for example, it opened a show of Bruce Davidson and Khalik Allah in its new exhibition space with an accompanying online presentation.

When planning began for the Magnum Learn webinar series “The Complete Guide to Selling Fine Art Prints”, I thought the panelists would advise photographers on how to adapt to a transformed market. In interviewing the curators, photographers, gallerists and collectors speaking on the panel, however, I soon learned how much of the business still works the way it has for decades.

Whether a photography dealer communicates with collectors in person in a brick-and-mortar exhibition space or a home office, via email or on the phone, their business still depends on their trustworthiness. Collectors are moved to own a photographic print for a variety of reasons, but few buy on impulse. Each wants reassurance that their purchase will provide them lasting enjoyment and value. First-time buyers also want to understand archival quality, numbered editions, stepped pricing and other terms unique to photography.

During the seminars, a collector and two curators will discuss what they buy and why, and photographers and gallery representatives will share their experience and expertise. The presentations will touch on some fundamentals of the fine-art business that can often confuse photographers used to working on assignments, but are important to understand in order to successfully sell limited-edition prints.

The Market’s Rules Seem Mysterious, but You Can Learn Them

Photographer/filmmaker Khalik Allah, who is speaking during the first session of the fine-art webinar, tells a story about the first time someone who saw his photos on social media asked to buy a print. Allah decided to announce he would make prints for $100 apiece. A curator and a collector saw his offer, told him he was undervaluing his work, and put him in touch with people who helped him learn a few principles about fine-art printing, and introduced him to a publisher and a gallery.

Pricing prints too low is a common rookie mistake, but it’s not irredeemable. “It’s a hell of a lot better than selling something that’s too expensive,” says Tom Gitterman of Gitterman Gallery, which gave Allah his first solo show in 2018. “You can always increase your prices. Decreasing your prices looks pretty lame.”

Allah learned the way most photographers do: by getting advice from experienced members of the photo community. In order to build a network of peers and advisers, photographers attend portfolio reviews, try visiting galleries and festivals, or ask questions of photographers they respect. As more galleries are posting prices on their websites, it is easier than ever to research how a broad swathe of photographers are setting their edition sizes and prices.

The Physical Print is a Coveted Object, an Expression of Your Art, and a Challenge

Amidst our daily bombardment of images backlit on a screen, the tangible print holds special allure. It is also an expression of the photographer’s vision. Photographers can choose the paper, print size and mounting they feel best presents their images, but these decisions affect cost, pricing, and sales.

Nancy Burns, associate curator at the Worcester Art Museum, says a big part of her job is overseeing the storage and conservation of the museum’s collection of photographs and drawings. When she wants to acquire a print for the museum’s collection, she has to consider whether she can store it in a flat file. A print that is very large, or mounted on glass or metal, creates work for the museum’s conservation team. If a photographer believes an image looks best at mural size, she says, they should follow their instincts while keeping in mind that fewer institutions will be able to buy it or store it. Her request to photographers is: “Don’t make it hard for me to give you a shot.”

Gallery owner Tom Gitterman says photographers sometimes produce prints just slightly larger than standard-sized mounts available. “That extra inch may be negligible in how the art communicates,” he says, but it can double the cost, because it requires buying a larger mount and glass and cutting it down to fit. Unless a photographer has a proven sales record and can fetch a high price for their work, they may be unable to recoup the extra costs. “Having those considerations in mind at the beginning could save some time and money down the road,” Gitterman says.

It’s Helpful to Look Ahead

Photographers are often driven by their next deadline, but selling limited editions requires a longer view. Photographers have to consider how their decisions could affect their legacy and the future value of their prints. By limiting a print edition, a photographer is guaranteeing that the value of a print a collector acquires will never be diminished by an unexpected supply of identical prints. It is essential to keep accurate records of how many prints are in each edition, and how many have sold. By keeping accurate sales records for themselves and their galleries, photographers prevent mistakes, such as selling the fourth print in an edition for the price of the fifth and sixth print. The final print in an edition sells for whatever price a buyer is willing to pay, and then the photographer is left only with their artists’ proofs. Selling out some editions can boost a photographer’s prestige among buyers, but some decide to save final prints or artist’s proofs from their best, most popular body of work. They may want to hold onto some equity, leave a legacy for their kids, or have something to offer when a prestigious museum calls to acquire a piece for their permanent collection.

Of course, it is possible produce more inventory. Photographers who continue producing new, thought-provoking, creative bodies of work burnish their reputations and excite interest in their earlier projects. It is useful to know which of their prints have sold or not, but to sustain a productive photography career, it is far more important to keep looking forward to the next project.

If you are interested in starting your own collection with Magnum, please contact Samantha McCoy, Gallery Director Paris.