Nanna Heitmann: Witnesses – When The Birds Will Fly Again

Nanna Heitmann on the time she spent photographing in Iraq on assignment for Médecins Sans Frontières, four years after ISIS had been driven out of the city

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders), a new book, Witnesses: 50 Years of Humanity, looks back at the major crises of the last five decades. Through the photos and words of those who lived through these events, it bears witness to the difficult mission of providing assistance. The collaboration, between Magnum Photos and Médecins Sans Frontières, available to buy here, was born of encounters that took place in the midst of crisis; whether in the world’s most remote regions, or in areas covered by international camera’s and media. The book is a historical document, made of common experiences that revisit the last fifty years – right up to the present day. Here, Nanna Heitmann shares stories from Mosul, Iraq in 2021.

Four years after the Islamic State group was driven out of Mosul by Iraqi forces and an international coalition, I was assigned to photograph the rebirth of Mosul – in the sense of its reconstruction, but also literally: in MSF’s largest maternity ward, where the number of births per month is reaching record figures.

In June 2014, an estimated 1500 fighters of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria seized control of Mosul, Iraq’s second largest city. For three years residents lived in fear of punishment according to the group’s extreme interpretation of Islamic law. Women had to be fully covered up in black, head to toe; minorities were persecuted; and public executions, arrests, and torture were a part of daily life. Most women I encountered spent all those years locked in their homes, unable to study or even leave their houses without being accompanied by a male member of their family. But there were also people, such as the midwife Kazal of MSF Nablus hospital, who had to work every single day, helping to deliver babies. Her son drove her to work every day at a public hospital; later, when the shooting got closer, women would come to her home to give birth.

When I asked Kazal about her daughters, she said they were housewives, they wanted to marry early and their husbands forbade them to study once they were married. She then looked determinedly at her niece and said she would never allow her to marry until she became a midwife, just like Kazal. Kazal told me how at first most people welcomed ISIS; they were building streets, treating citizens nicely. Only as the months went on did they slowly force men to grow their beards, and women to cover completely in black. It got to the point where girls would be executed just for wearing brown instead of black socks.

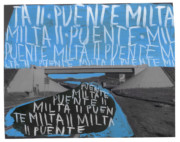

In December 2016 the Battle of Mosul started. It was only in June 2017 that the western part of the city was liberated. The Old City of Mosul in particular presented a complicated battlefield due to its narrow streets, where no tanks could fit. On my first day in Mosul in 2021, my fixer Sangar Khaleel took me to what was left of the once beautiful, historic city. As we climbed and stumbled through the ruins, we kept coming across human bones and the remains of explosive belts. I noticed how my knees inevitably became shaky and my heartbeat stronger. While Sangar was on the phone, I was about to enter a destroyed house until I heard Sangar running after me. At the entrance to the house, an inscription in Arabic warned of mines that might not yet have been cleared.

The people’s stories from the war and the amount of destruction I saw only allows me to quietly guess at the horrors the people here must have experienced and I felt helpless trying to tell their story. I would never be able to fully understand or imagine it, as a foreigner who had never worked in the Middle East.

At the MSF Nablus hospital, on the outskirts of west Mosul, I thought I would photograph a positive story of “rebirth”: Mosul coming back to life after so much grief and loss.

But that first day I encountered many women who had experienced miscarriages, and women who felt too weak and drained to talk.

I met Lana, a psychologist from Lebanon. She was impressed by the women’s resilience but explained that the rates of postnatal depression, impulsive behaviors and self-harm were extremely high.

“My only hopes are for the next generation. People are highly traumatized here because of ISIS, and ISIS has increased rates of aggression in society. Men are used to aggression; they are used to violence. ISIS was modeling this kind of behavior, this domestic violence, and it changed people’s mindset.”

Lana often raised the term “emotional blindness”. People were under attack for three years. According to Lana they reached a place where they could not feel anything anymore. They became emotionally blind. This was a coping mechanism, helping them to survive the cruelty of war. But even when the threat wasn’t there anymore, the coping mechanism stayed with them. Emotions had not really been processed. Her hope lay in future generations, because the current generation had been too severely traumatized to heal. Personality disorders were extremely common.

At the same time, it was election campaign time in Iraq. After waiting for more than an hour in a busy office of her party, we met Basma Baseem, who had been the first Iraqi woman to become head of the city consul in Mosul, only three months before ISIS took over the city and established their caliphate. Even before ISIS she had survived bombs that were attached to her car and had received dozens of threats. ISIS took all her belongings when she fled to Kurdistan, but by the time we visited, she said she felt safe to move around Mosul by herself.

In the garden of her office, men, young and old, many dressed in traditional tribal clothes, came to see and speak with Basma and to seek help. Sitting together in a circle they asked questions and discussed the problem of high unemployment in their neighborhoods and the lack of prospects.

Basma’s biggest worry was the families and children of ISIS fighters left behind, who, she said, were a time bomb.

In Qaraqosh, an Assyrian Christian town close by, the horrors of war and persecution felt almost forgotten. Only the number of empty houses, between renovated houses, served as a reminder of how many people didn’t dare return home but left for other countries. In the evening, more than 4000 people gathered together; women, men and girls danced exuberantly together at the Feast of the Glorious Cross. Sangar tapped happily to the songs with a beer in his hand, saying he had never seen so many people mixed together, partying, anywhere in Iraq.

Later, the Iraqi singer Adnan Al Rassam performed a song about marriage: “Girls don’t believe that marriage is a joyful thing. The first week you are at home and it’s pure happiness. The second week you are just like apples and sugar. You are so spoiled in the second week. Third week you are on the ground like a broom, cleaning everything. Fourth week with your mother-in-law starts the fighting. Fifth week you are going to your father’s house because you are angry at your husband and his family. Sixth week you are at the court, always there, for the divorce process. Seventh week you are divorced and you are so happy. Girls don’t believe anyone who tells you getting married is good.” It seemed to be familiar to everyone, and people clapped and laughed together.