Magnum x Prix Pictet: Cristina de Middel & Olivia Arthur

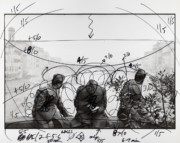

Organized in partnership with Prix Pictet at this year's Photo London, two Magnum photographers talk to Katy Hessel about the power of ambiguity and uncertainty.

Magnum is celebrating its 75th anniversary throughout 2022, with events continuing this September with exhibitions and talks in Berlin and New York. The program began at Photo London in May with a collaboration between the agency and Prix Pictet and a talk co-hosted by art historian and broadcaster, Katy Hessel, founder of the The Great Women Artists.

Hessel led a conversation between two Magnum photographers: Olivia Arthur, speaking in the last month of her role as president of the agency, and Cristina de Middel, who would be voted in as her successor a month later at an AGM in New York City. The conversation, however, revolved around their parallel practices.

Hessel began by asking each photographer their views on the continued power and potential of the still image. Both pointed to the inherent ambiguity of photography as a strength rather than a weakness.

“For me, it’s it’s what is left unsaid,” says de Middel. “As animals, we are very time bound. The way our brain works, we need sequences. It’s how you become literate with images. You take a fraction of an action, and you imagine what would happen after. For me, that’s the power of photography, because it is very much linked to reality, but it also activates our imaginations.”

“It’s also not knowing what exists outside the frame,” says Arthur. “It leaves space to draw people in, to let the audience be part of [the narrative]. If you watch something on TV, it’s quite passive. When you look at a still image, it gives you the opportunity to think about it and engage with it.

“It’s also about how you put images together. I am really interested in the series, rather than the single image, and how you tell stories. There is space between the pictures; you jump from one thing to the next and build your narrative from that.

“I use text in there as well, and I use text almost like an image, giving just a snippet. It’s not telling the whole story, it’s just giving a hint of something. So, as a viewer, you have all these little pieces to put together in a way that makes sense for you. And I like to think that it’s slightly different for everybody, and that’s the ambiguity.”

These themes play out through the rest of the talk – which can be seen in full in the video above – as each photographer discusses key turning points in their careers in relation to finding their voice within the line between fact and fiction. De Middel reveals some of the thinking that led to her breakthrough series, The Afronauts, and Arthur talks about the challenge of photographing women in Saudi Arabia for Jeddah Diary.

"I have a very tense or conflictual relationship with truth as an idea."

-

Inevitably, this led to a conversation about contemporary ethical concerns. “There’s been an evolution since I started – since I self-assigned myself the mission of saving the world with photography, or at least making it a better place,” says de Middel.

“Now, my expectations are a bit more in control. For me, half of the picture is mine, half is of the person I am photographing. And I really want it to be understood like that. I have a very tense or conflictual relationship with truth as an idea. And I find it funny to play with it. But with my work I try to be very honest with the subject. It is important that I explain everything I am going to do with the picture, and what I think it’s going to become and what I think it will mean. I also keep myself very open to the other person.”

Hessel points to the sense of collaboration inherent in de Middel’s work. “I think it has to be like that,” says the photographer. “It was not like that five or 10 years ago. You would not show your work to the person, it was a question of trust. Because photography was trustful. But now things have changed.”

“There’s also the question of the way you do it,” says Arthur. “Because you hit against these questions for yourself: you take a picture and you run away, so what are you doing with it? I changed my camera and started using large format, which is really big and cumbersome. You put it on a tripod and you talk about what you’re going to do and you measure the light, and there’s no surprise – you’re not grabbing a picture. So the process of making a portrait in that way is collaborative in the sense that it’s very open, it feels very honest, to me, I really responded to that process and I carried on photographing in that way for a long time.”