Theater in Extremis in Cracolândia

Alex Majoli discusses the most recent addition to his long-running series, 'Tudo Bom', documenting life and hardship in Brazil. Interview by Danielle Ezzo.

When Alex Majoli first traveled to Brazil 20 years ago, he set out to document the darker side of the country’s complex society. The project, which he has titled Tudo Bom – ‘all is well’ – is still ongoing, and earlier this year the photographer set about exploring the district southwest of Såo Paulo’s Luz station, commonly known as ‘Cracolândia’, in reference to the public sale and use of drugs.

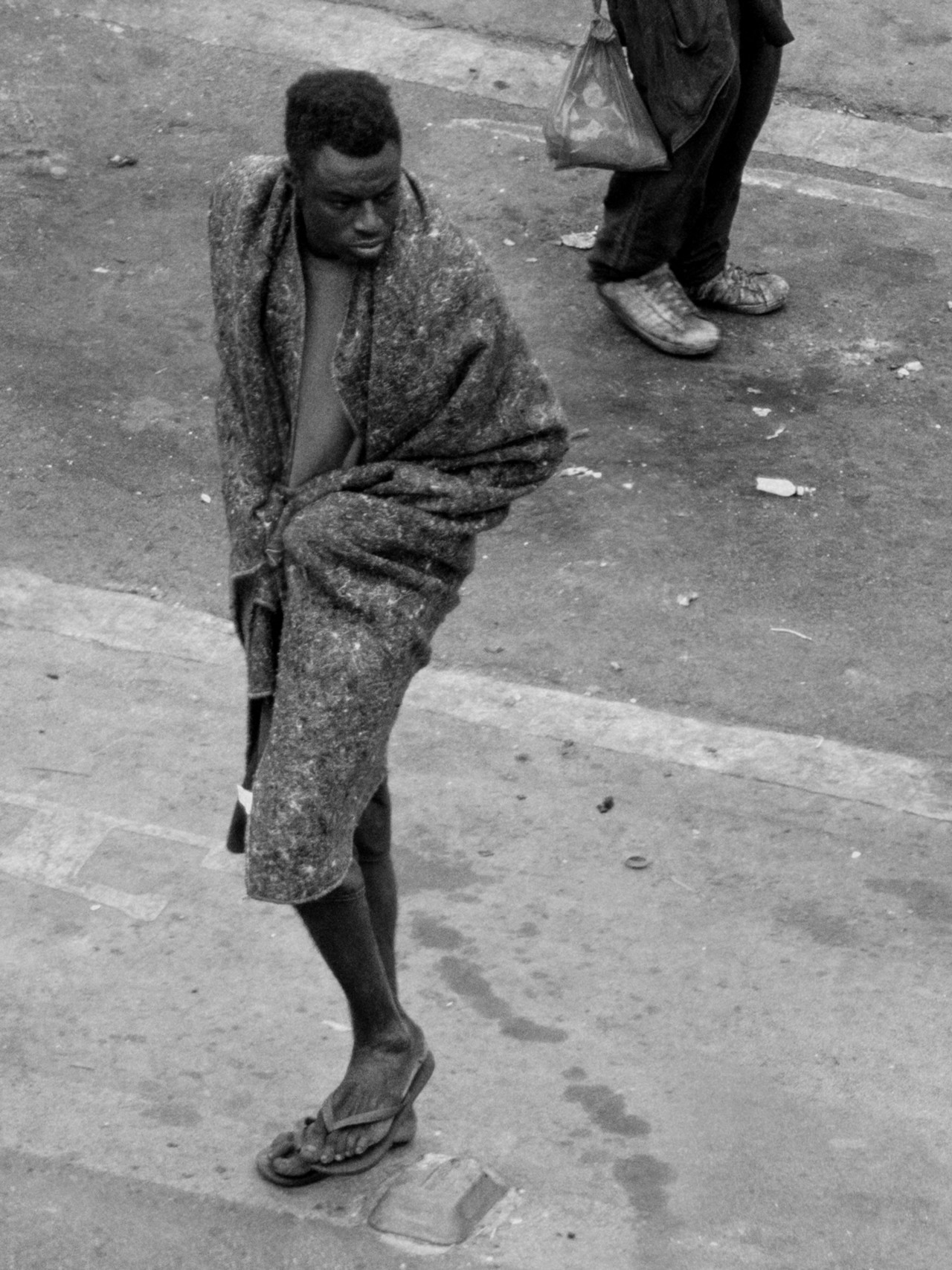

“Some call it a human zoo or a horror show, others a zombie tourist attraction or Brazil’s shame. Drug users, many wrapped in dirty blankers, lie on the pavement or are slumped on stained sofas. Others shuffle along the road, seemingly oblivious to their surrounding,” is how Cracolândia was once described in The Guardian, a quote that Majoli uses to introduce this new collection of images.

The series fuses documentary photography with Majoli’s fascination with the theatre of everyday life. “The photographs will retain the DNA of photojournalism, in the strict sense of providing content regarding current events, but will bring into play an aesthetic that highlights what roles the various characters in this crucial chapter of contemporary history have been assigned,” Majoli explains.

Inspired by Italian playwright Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author, Majoli describes his fascination with the theatre of everyday life: “I realized that we all play a part. We wear masks that accommodate fixed societal roles, and in that way, we are all trapped in our own play. Here we are, relentlessly acting ourselves. A key to understanding our complex reality, then, could be to acknowledge and question the meaning of the theatrical elements that have constructed its play, our core social narrative”.

"We are all trapped in our own play.

Here we are, relentlessly acting ourselves."

-

In the edited extract below, Danielle Ezzo, a contributor to Obscura Journal, interviews Majoli about the Tudo Bom, the limitations of photography, and how he uses photography to capture the theatre of everyday life.

The final edit of 55 images is the latest collaboration between Magnum Photos and Obscura. The full collection is now available to purchase as NFTs and can be viewed here.

Danielle Ezzo: Tudo Bom, meaning ‘all is well’ in Portuguese, is a continuation of work you’ve been doing in Brazil for some time. The pandemic has amplified the economic and safety concerns in the country. Can you speak to what you were most concerned with, in the present moment, when documenting Brazil and the main concern with this project?

Alex Majoli: I wanted to use ‘tudo bom’ as the title of my 20-year project because those two words contain all the contradictions of a country. Every day, Brazilians repeat the phrase as an exorcism for a hard life. About the consequences of the pandemic in Brazil – yes, it created more instability than it did for the rest of the world, but Brazil has within itself an endemic social disparity that seems, day by day, untreatable.

"I realized that what was happening around me was bigger than just a theater of life. There was movement, unconsciousness, rhythm entering the ‘square of crack’; like a real religious procession."

-

DE: There are some images that are taken from a high vantage point, further away from your subjects, that have a surveillance aesthetic. Which is to say, very removed. Can you walk us through how you took those images and what was the reasoning behind that particular vantage point?

AM: For days, I was creating my scenes. There are pictures in close range with flash, but I realized what was happening around me was bigger and stronger than just a theater of life. There was movement, unconsciousness, rhythm entering the ‘square of crack’; like a real religious procession.

I thought that the procession needed to be my reference. It’s the crossroads that give us access to the square and could contain a kind of worship — all the wakefulness of a rite. I didn’t think or didn’t intend with that vantage point to have a surveillance aesthetic. Although now reading your questions, I can see that I was searching for a wide-angle view. I’d just like to remind you that those images are cuts — extracts from one big, large-scale image — and are details of a landscape.

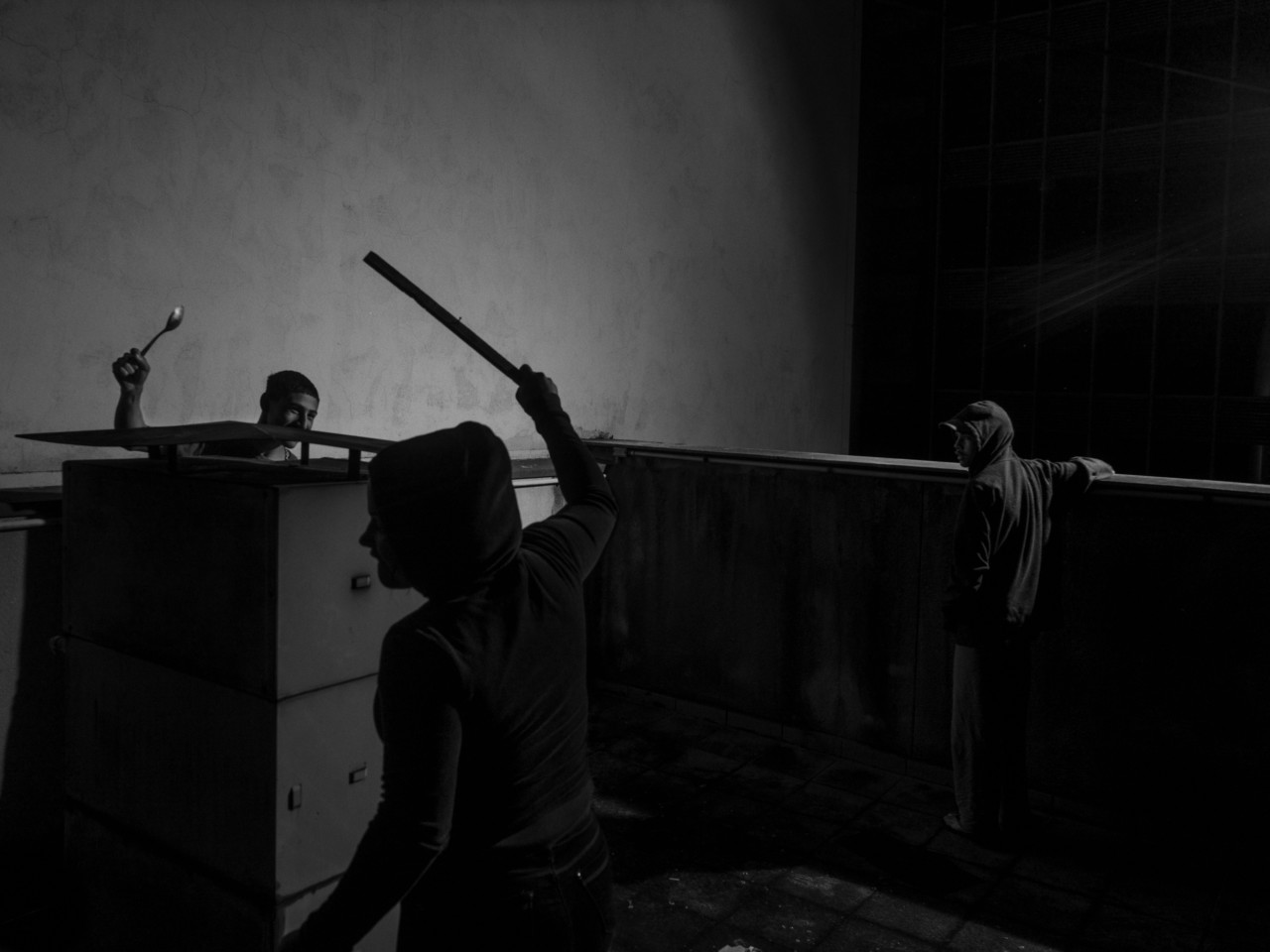

DE: The images you took on street level, even though they’re more intimate, have a tableaux quality to them. Each is a drama that is unfolding before the viewers’ eyes. What do you consider a successful image in making these particular photos and how do they function compared to the more distanced images?

AM: Yes, the idea of tableaux is correct and it is the aesthetic I choose for this long-term body of work called Scene. It’s been almost 20 years now that I’ve been trying to explore and experiment with the concept of us ‘human beings’ acting our roles in society. At first, I was trying to catch the ‘mask’ of us in society. Later, after a series of little concept failures, I needed to add the stadium, which for me is the scenography of our society.

I had the intuition in 2008 to create a skene (as in the ancient Greek ‘scene-building’) to reference the real life of people. The ‘performance’ of me building that ‘skene’ around people or events of society, and then my subjects, all of a sudden, becoming protagonists of an unwritten play; their own play. That performance/skene/acting pumps the real into ‘more real’ having the aesthetic ambiguity of the fiction. It freezes the improvisation of our ‘acting’ in society.

How do they function compared to distance images? I personally think they are the same, maybe one is under the spotlight with ‘the observer’ on the other side of the fourth wall seating in the theater stalls, and the other may be in a street theater seating in theater balconies.

DE: What is happening in the image above? It looks like a man is singing in empty stadium seating.

AM: We are inside one of the many evangelical churches that have been converted from cinemas. Brazil, over the last few years, became the number one evangelical country. This type of building is prevalent. Basically, this man is praying in a cinema. How can reality be more fictional than this?

"Photography is a prison to be escaped."

-

DE: In your artist statement, you mention being influenced by the Italian playwright Luigi Pirandello and this idea of the ‘theater of everyday life.’ Can you expand on how photography, moving images, and this idea of theatre overlap in your work?

AM: I always felt confined by all the limitations of photography, but I love challenges because I think through challenges you have a better understanding of yourself. Photography is a big challenge; it’s a prison to be escaped. I always try to contaminate languages and break the walls between different modes of communicating.

After many years of walking with a camera on your neck, you start to see all those steps you’ve made the day before. You start to feel frustrated when you recognize details that stay the same. At that moment you start to question, “what if…?”. In my case, the way to punch through those restrictions was by using the visual language of theater, literature, and the idea of the banal. It is a need, it is an escape, and eventually could also be a place where to hide your imperfection, your insecurities.

DE: Can you explain what’s happening in the image above?

AM: To be sincere, I don’t know. I thought it was magic. I thought the figure in the center was talking to God maybe. I thought he was thinking of some relative’s death. I love the ambiguity in photography as in life. Pirandello’s famous quote recites, ‘It is so if you think so’. We relate to images that we can decode or we recognize the universality of them. What’s for us in the sky besides clouds and birds? Each of those people in that photo is in their dreams — isn’t that exceptional?

DE: Talk to me more about the tension with the police. It’s clear in several of your images that there is active friction.

AM: Yes, unfortunately, it happens in all the countries where social injustice reigns over the interest of a few. It is a silent civil war, in Brazil as in many other countries.

Read the full interview here.