Erich Hartmann at 100

On the 100th anniversary of his birth, we pay tribute to Magnum photographer Erich Hartmann with a selection of his most iconic images.

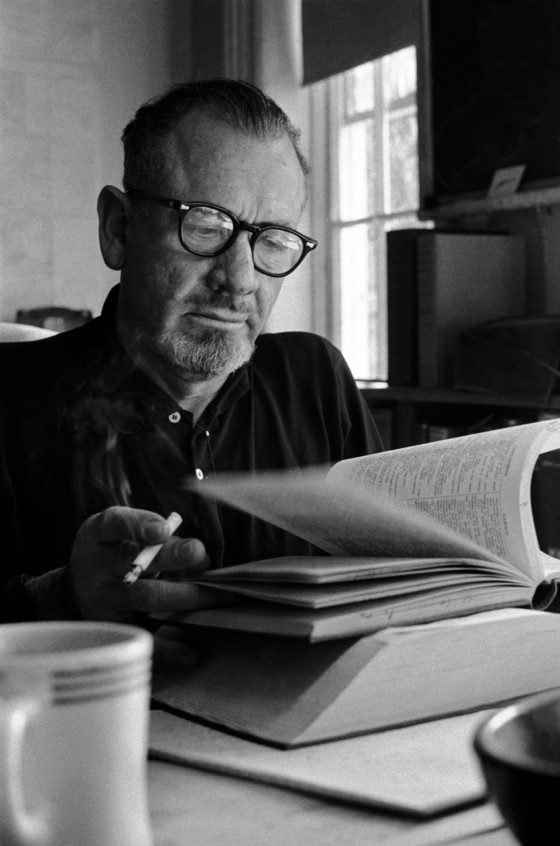

Erich Hartmann, who would have been 100 years old today – July 29, 2022 – was a quintessentially 20th-century photographer, both in the story of how he came to be an image maker, and in his pioneering of emerging practices.

Born into a Jewish household in Munich in 1922, little more than a year before Adolf Hitler led the Beer Hall Putsch, he and his immediate family escaped to the US shortly before war broke out in Europe, only to return again five years later as an American soldier. He served in England, France and Belgium before enlisting as a court interpreter at Nazi trials in Cologne, then moved back to the US, settling in New York City. There, he married, had two children, and pursued his interest in photography, studying under Berenice Abbott and Alexey Brodovitch at the New School for Social Research, and later working as a freelancer, making his name with his work for Fortune magazine in the 1950s.

Robert Capa invited him to join Magnum that same decade, and he would later become the agency’s president, in 1985, having served on its board of directors for many years.

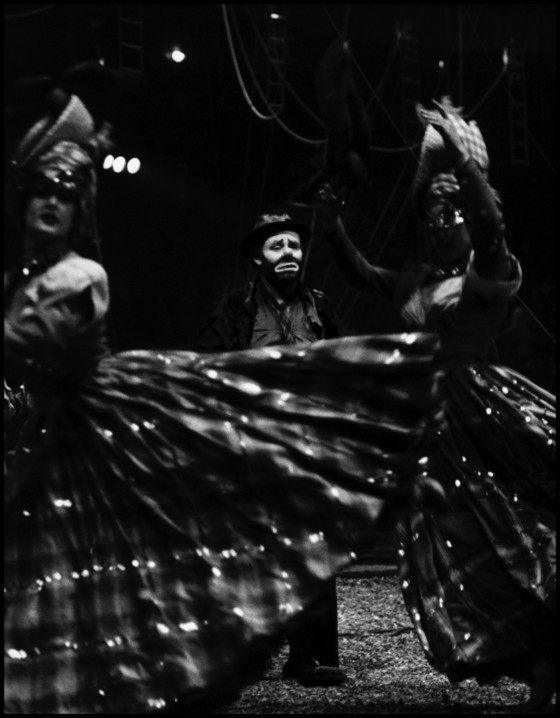

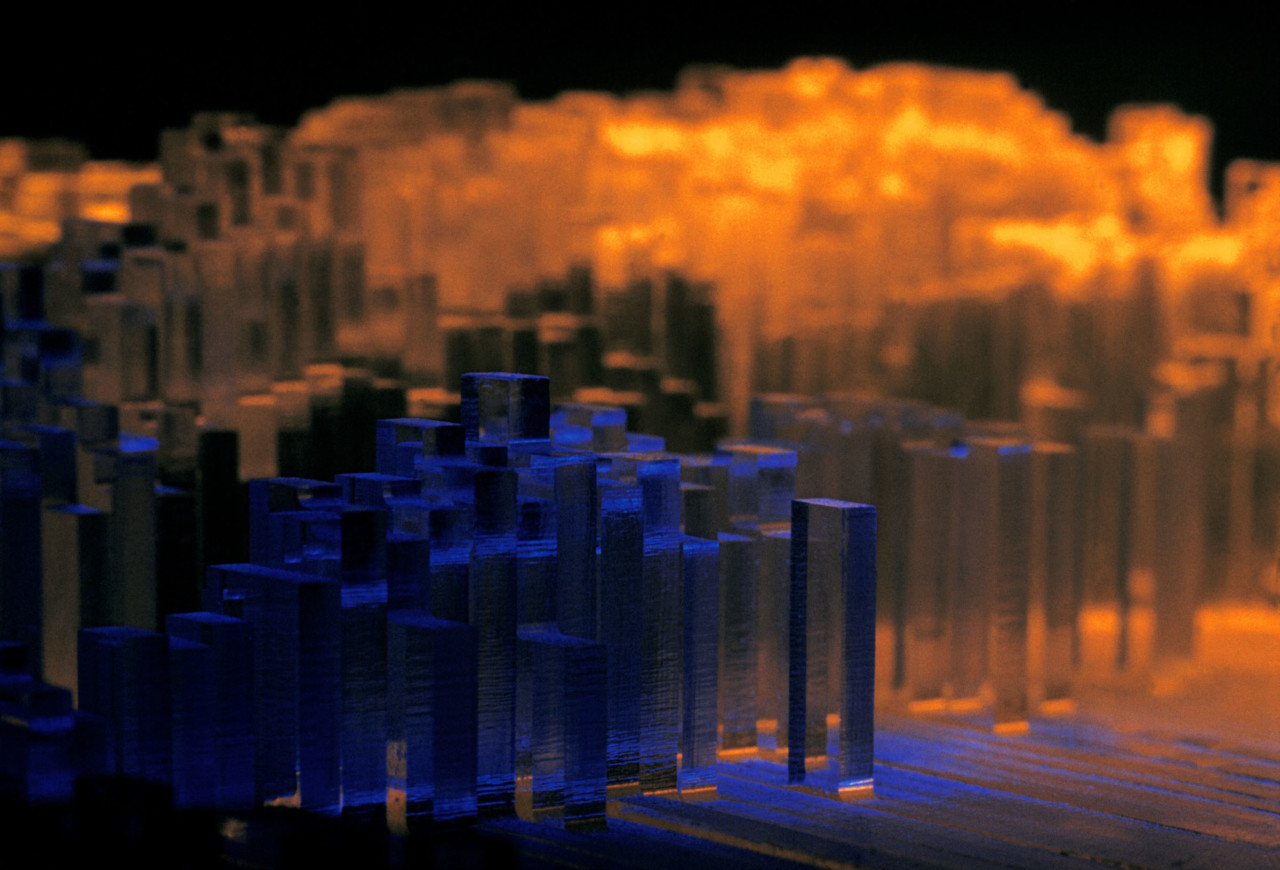

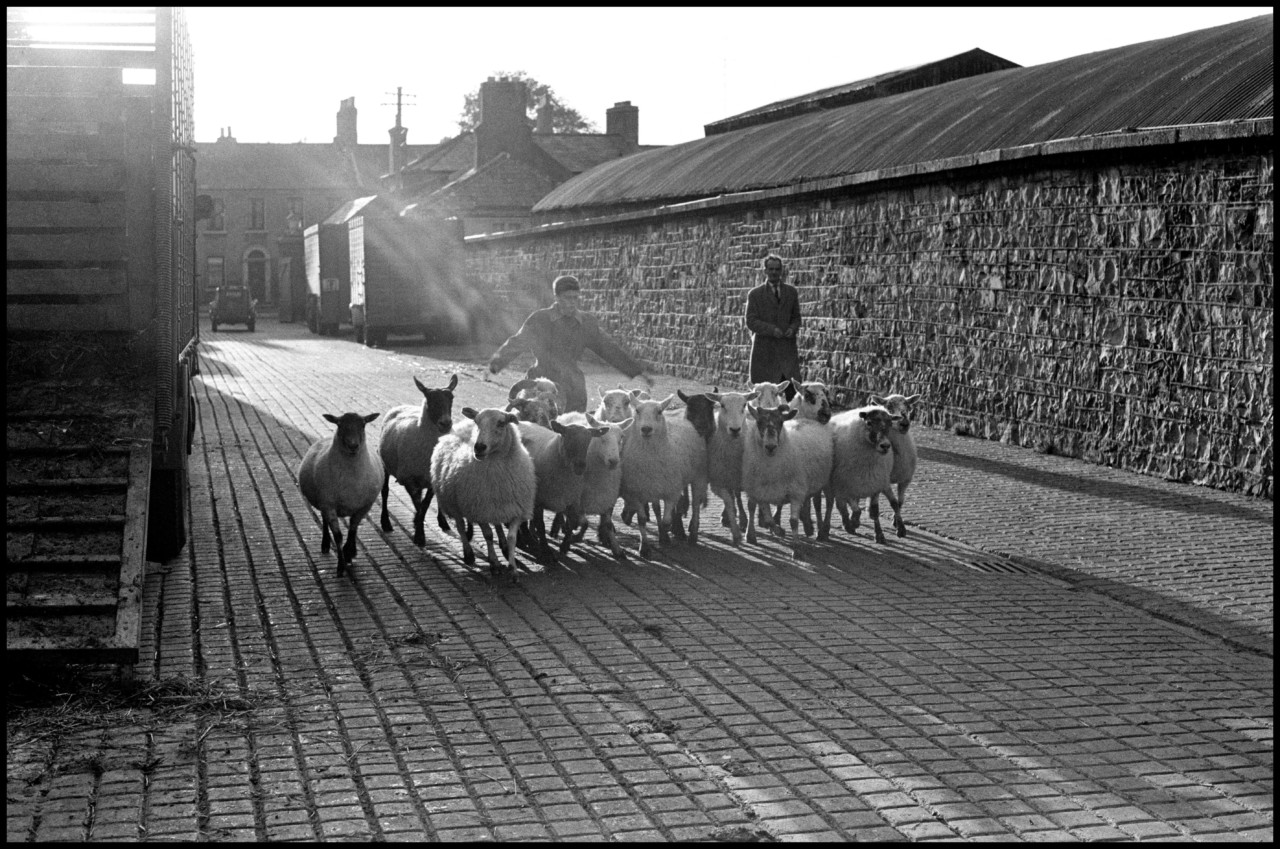

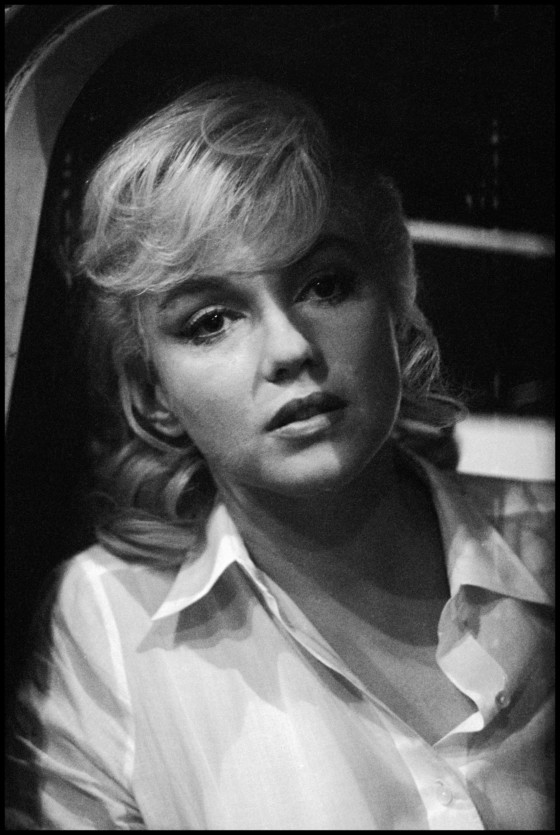

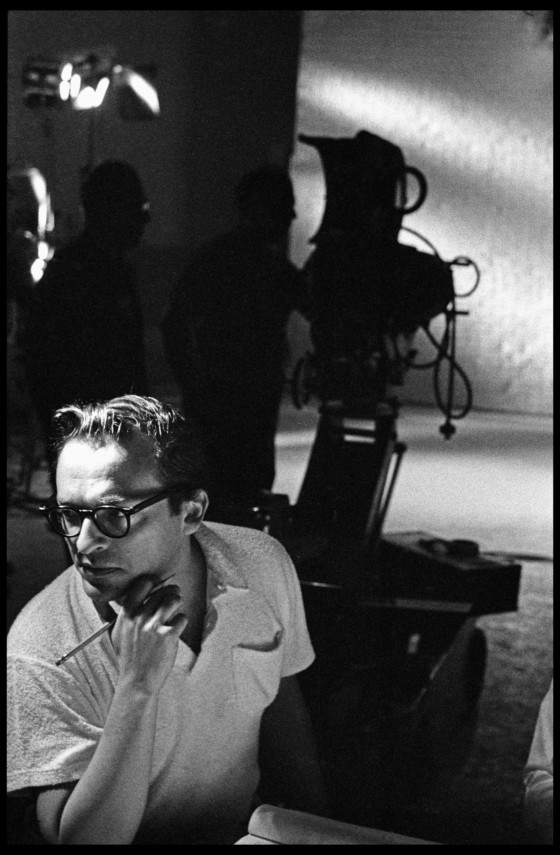

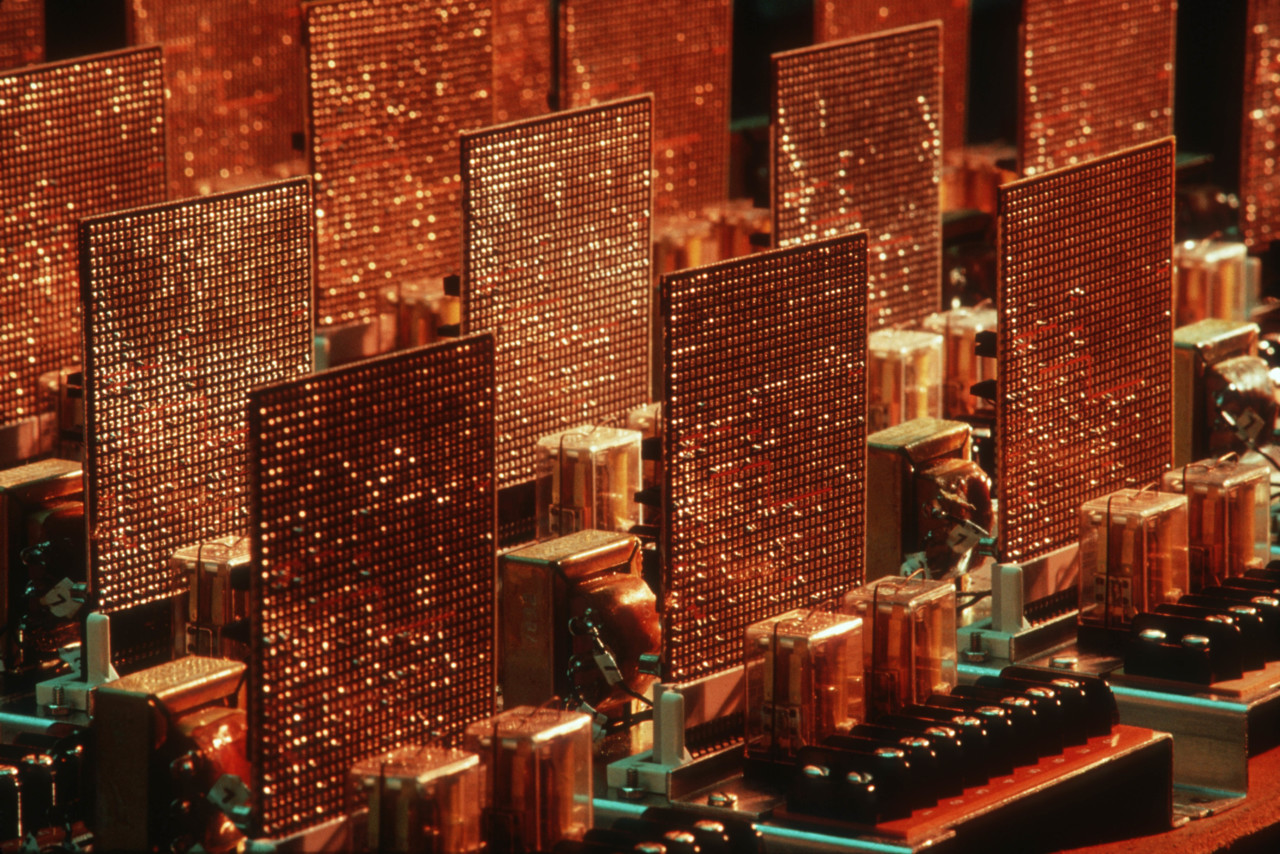

Hartmann was known for his poetic approach to subjects including science, architecture and industry, evident in photo essays such as, ‘Shapes of Sound’, ‘The Building of Saint Lawrence Seaway’ and ‘The Deep North’. He traveled the globe carrying out assignments from newspapers, magazines and corporate clients, but throughout his career, he also pursued long-term personal projects, many with literary echoes, such as Shakespeare’s England, Joyce’s Dublin, Hardy’s Wessex.

He is perhaps best remembered for Our Daily Bread, his magnum opus, eight years in the making, shot across four continents, including land workers in Israel, combine harvesting in Nebraska, a miller in rural France, a soup kitchen, a Paris bakery, grain barges on the Mississippi, Bedouin in Beersheba selling grain at market, traders on the Grain Exchange, a school cafeteria.

He staged a large exhibition of the work in New York in 1962, but it was not published as a book until 14 years after his death. His wife, Ruth Bains, aptly described it as a “lyrical tribute to the men and women everywhere whose daily work helps to create the bread which feeds us all and which has become a metaphor for sustenance… a picture-poem of the significance of bread to us all.”

"He was always wise, judicious, and ferocious to find the right answer rather than the easy one."

-

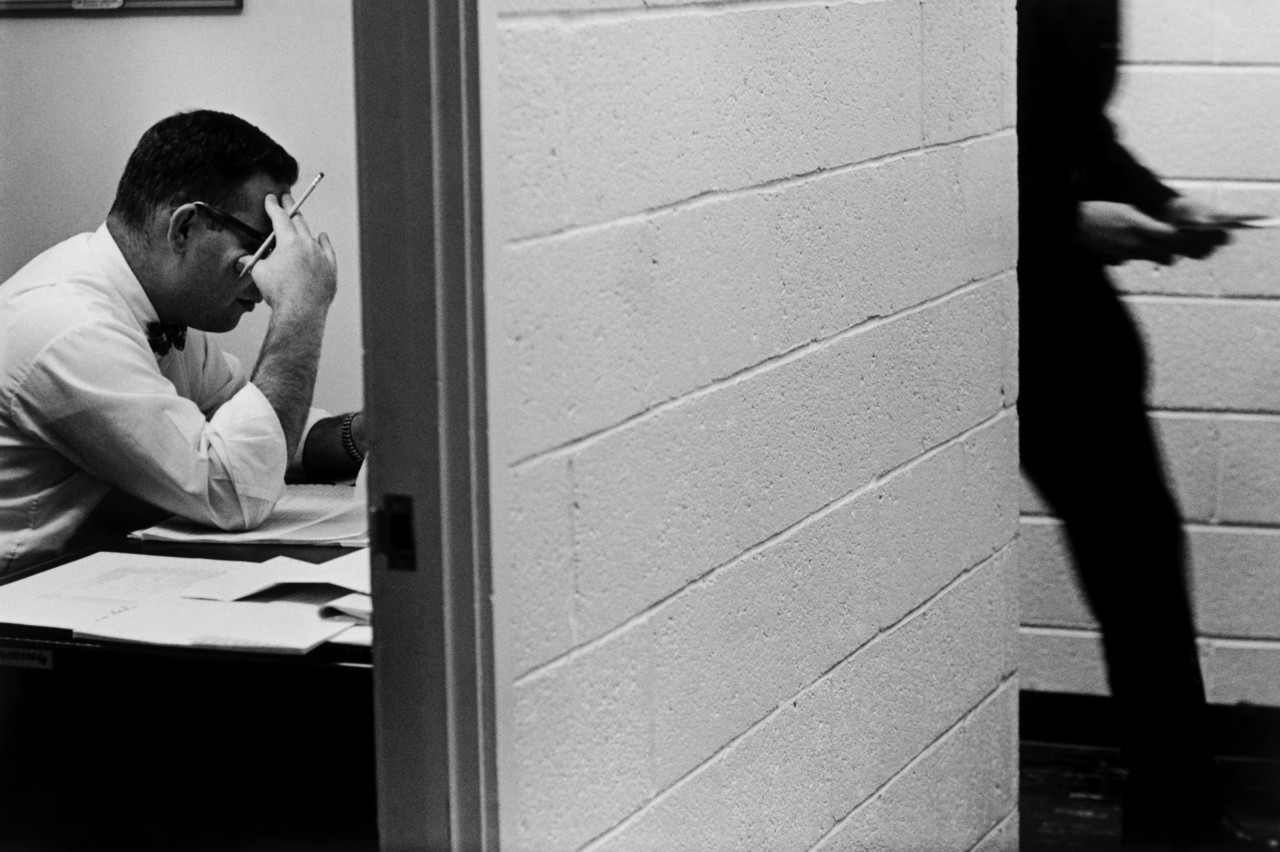

What is less well remembered is that he was a pioneer of color and of a new branch photography. “He was the first to bring the techniques of photojournalism to corporate photography,” wrote his Magnum colleague, Eve Arnold, in an obituary in The Independent. “By his example, he opened an entire new field for photographers whose main venues were newspapers and magazines.”

In the same piece, Burt Glinn was quoted saying, “Erich, more than anyone else, has been my moral compass. No matter how knotty the problem he never settled for the facile compromise. He was always wise, judicious, and ferocious to find the right answer rather than the easy one.”

"I simply felt obliged to stand in as many of the camps as I could reach, to fulfill a duty that I could not define."

-

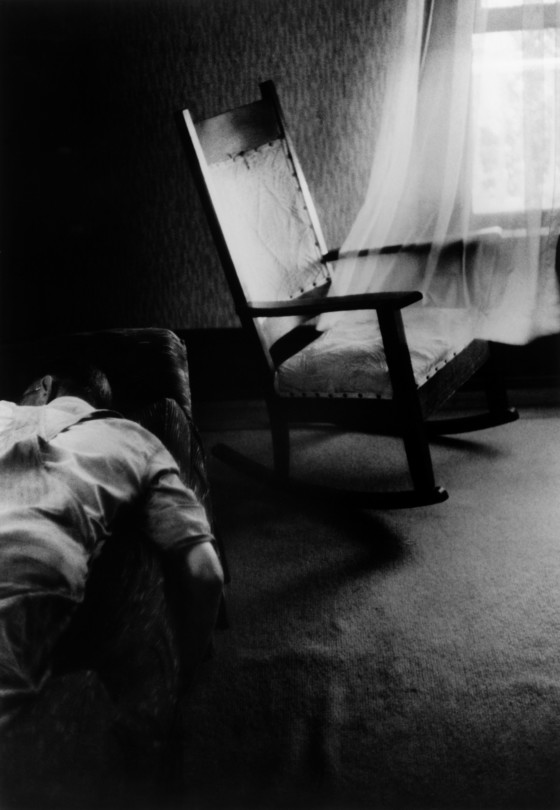

In his later years, Hartmann photographed the remains of the Nazi concentration camps, resulting in a book and exhibition, In the Camps, in 1995. He said of the motivations behind the work: “I simply felt obliged to stand in as many of the camps as I could reach, to fulfill a duty that I could not define and to pay a belated tribute with the tools of my profession.”

He died in 1999.