Winter Solace

In part two of his interview with Jacob Aue Sobol about his latest book, James' House, Colin Pantall talks to the photographer about the harsh beauty of everyday life in a remote corner of Greenland.

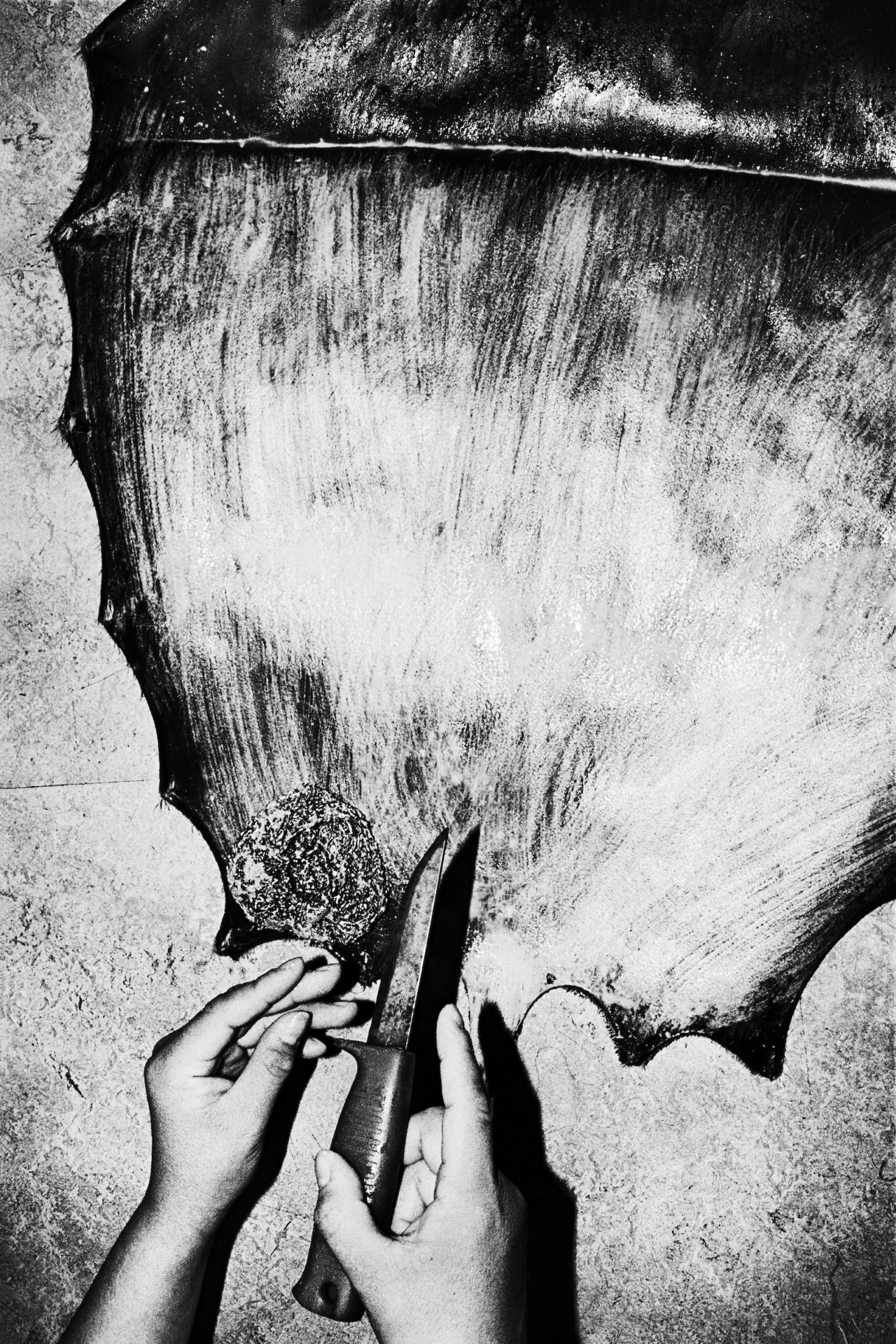

James’ House is a book about hunting. There are images of seals being hunted and skinned and eaten. There are pictures of fish lying on the ice waiting to be gutted, rows of halibut and spotted wolf fish lined up on the ice. There are fishing holes, harpoons, and sleds to take the hunt and catch home.

The book is the second in a trilogy about Greenland by Jacob Aue Sobol. The Danish photographer first travelled there in 1999, staying on in the isolated settlement of Tiniteqilaaq after falling in love with a local girl, and then later making a book about their relationship, titled Sabine. Eighteen years after that book was published, Sobol is making a new book back on his time in Greenland, this time about James, one of the men who taught him to hunt and fish, the man whose home he spent so much time in.

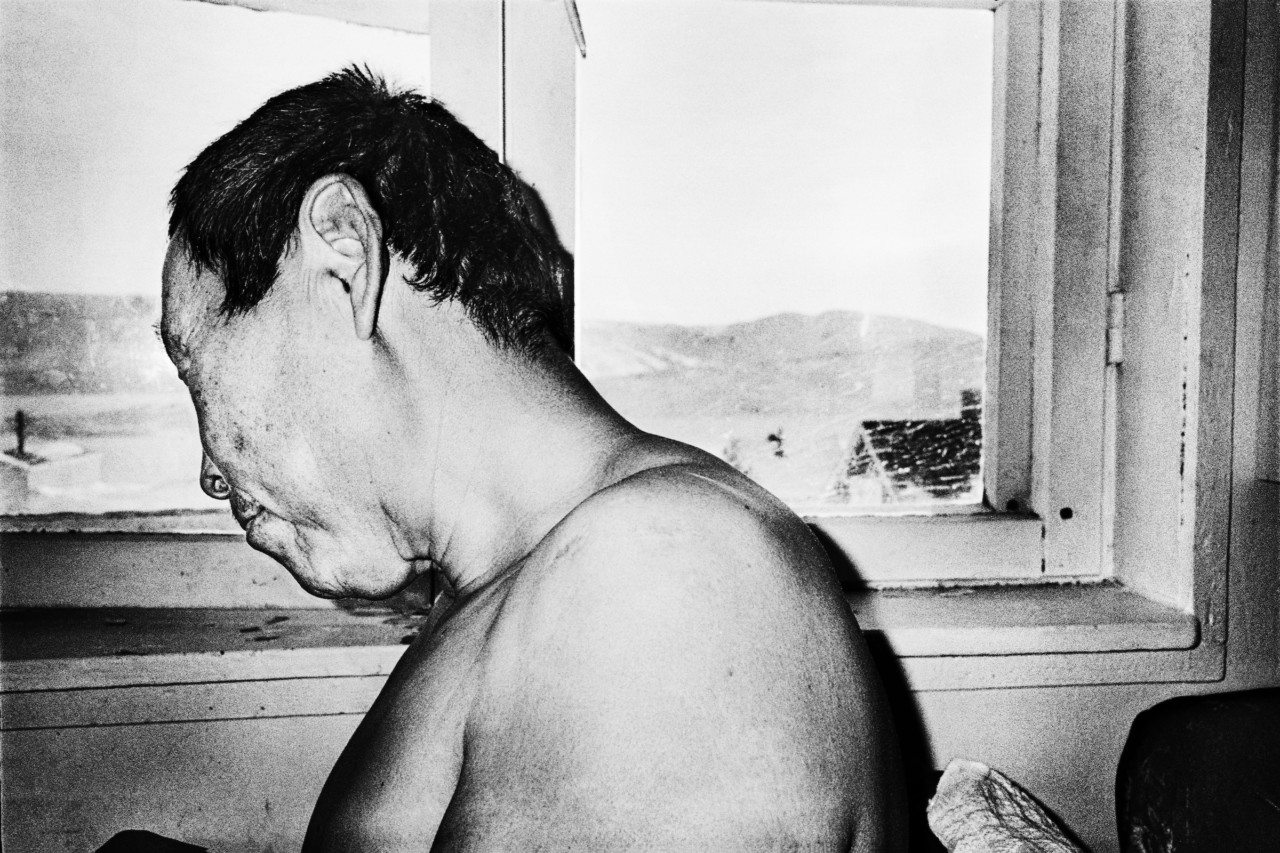

There are images of the environment. The first picture shows James standing over a snow-covered body of water, feeling in the snow for the ice below. The next image shows a fishing hole with a net coming out half frozen.

This is winter in Greenland and, straight in, Sobol is telling us something about the harshness of being out on the ice, and the resilience that is needed to find food for the family and community you are part of. And then once the hunting is done, that is when a different life begins. That is when food is brought back into the home to be shared, to be cooked, to be eaten.

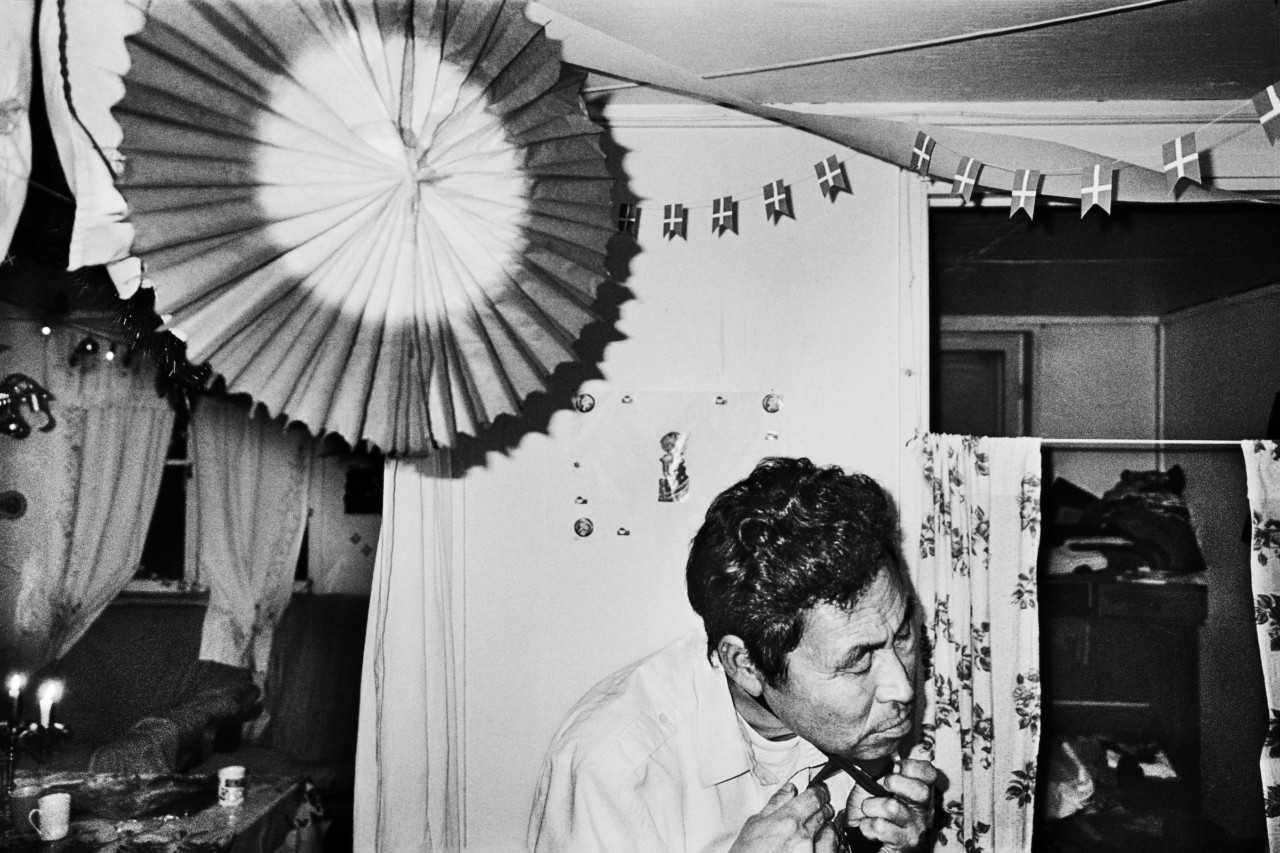

“The family is probably the centre,” says Sobol, “and the home is so important. I don’t want to romanticize their lives because it was also tough, but it was alive. It felt like the centre of the universe, that house. It was where everything happened; there was laughter and tears and all the beautiful things in life, but also the more difficult things that took place there. For me the closeness that I experienced in that home is something that I always yearned for and that I now have.”

In all of Sobol’s work, there is an attempt to get close to people through the physical closeness of the camera and that is evident in the pictures from James’ House. He gets in amongst children’s bodies as they dance and play, he moves low into the carpet as a father and child put their hands on the floor, a walrus plushy looking up at us as he photographs. Children are cuddled and comforted, card games are played, television is watched, and a surge of physical energy emerges from the pages.

That energy and warmth came with a darker side. At the time the images in James’ House were made, 150 people lived in Tiniteqilaaq. There was no internet, and it was an isolated community with fewer opportunities than the more populated west of Greenland.

“There were young people that committed suicide,” says Sobol. “I think the family’s way of finding a way to accept it was difficult. If you are in this small settlement, you don’t have that many choices. You need to keep on living in some way. I remember this family who had lost a child, that the father, he went hunting a few days after and he came home with the seal and the mother was there cleaning the fur and so on. I was shocked. And at the same time, there was some kind of admiration that they were able to do this.”

In James House, the beating heart of the domestic interior is set into a seasonal visual rhythm with the harsh beauty of the outside world, by the life and death struggle to survive in such a harsh environment. “It’s not a joke. You have to be aware almost every step you take. You have to learn about how the ice moves and when the ice is thick enough to walk on and when it’s not, and when there is danger and when there’s not. Just the stream and the movement of the ice can make it impossible to get home. So even though things seem very peaceful, the dangers are just around the corner.

“And it’s cold. I mean, I always enjoyed really cold weather because when it’s the same all the time, it’s boring. I remember waking up every morning in Bangkok [where he lived for a while] and walking out onto the streets. It was like walking out into a wet fart. I like the cold.”

“We caught cod, halibut, salmon, trout, catfish, and rockfish. Trout and salmon are near the surface, but the halibut and the rockfish are 500 meters down. Or even more. The lowest I went was 700 meters down. You make a hole in the ice, you have this piece of the wood with 800 meters of nylon fishing line around it, and you put your bait on and feel when you are at the bottom. And when you feel a bite, you pull the first 20 meters very fast. Then you can feel if the fish has hooked – because you don’t want to pull it up 800 meters and then find out that there is nothing there.”

“Some days the fish are there and some days they’re not. But when it went really well, we could bring home like 100 trout or halibut. There’s a picture in the book with of a tent we put up as sometimes we would stay there overnight and fish. There’s always more fish in the morning, right? And in Greenland in the summer it’s sunlight 24/7. So when we went on these trips, we would come home with a lot of food. And then the beautiful thing is also that you share what you come home with. It’s not only for your family. It’s also for the other families or the elderly in the settlement.”

“Sometimes when we were out fishing, we would sit in a small boat for eight hours without saying a word, and it was not hard. It was not wrong. It felt good. That made me feel at home there. We are all different. I’m an introvert. And, when I was there, I just felt that I didn’t have to be outgoing. When I have to be social in our world, I always get anxious and nervous. In Greenland I felt at home because they don’t expect you to chit-chat. It was okay to be quiet and I loved that so much.”

Read part one of the interview, in which Sobol discusses his first photobook on Greenland, Sabine, here.