Village People

During the early 1990s, when Martin Parr came to international fame for his work exploring issues of taste and class and the emergence of globalization, he spent one year working one village. Thirty years later, reports Colin Pantall, the photographs have been turned into a book.

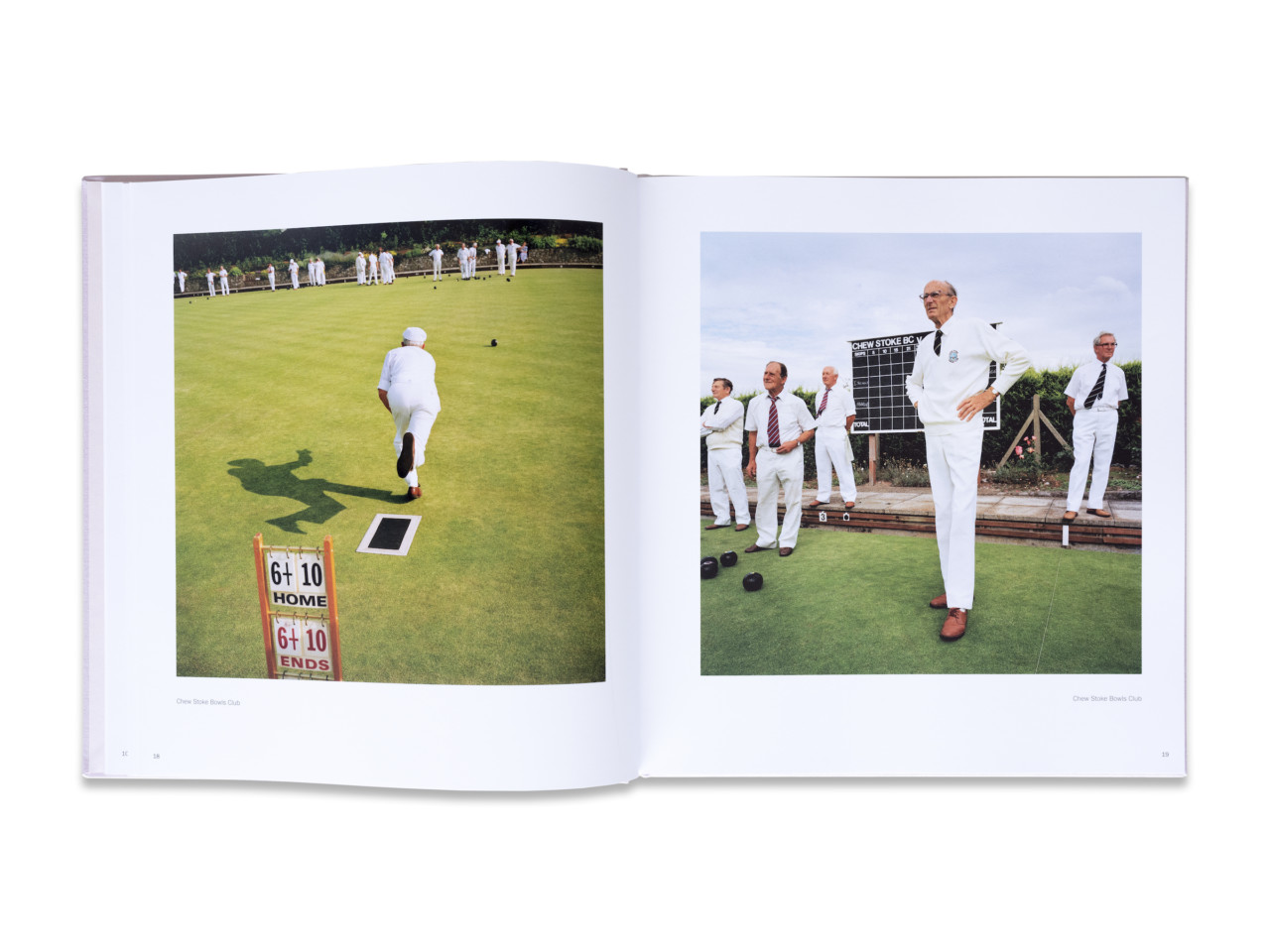

Open up a copy of Martin Parr’s latest photobook, A Year in the Life of Chew Stoke Village, and you step back in time to 1992.

In the first picture, the day starts early as a milkman delivers his bottles to the terraced houses that lie behind the village centre. The sky is blue, the roses are in full bloom and all is well in Somerset. Turn the page, and we see a family of commuters as they begin their daily journey to Bristol. The father, an accountant, makes the 35-minute drive with two boys on the back seat, ready to be delivered to the private grammar school in the city’s affluent Clifton area.

Signed copies of the book are available in the Magnum shop.

"To look at what’s going on in one village and photograph it quite carefully and intensely – I’m proud to add that into my archive."

-

A 15-minute walk up the road to the other side of Clifton, and there is a man loading up his camera bag. His name is Martin Parr, and he’s about to set off on the reverse journey to photograph Chew Stoke for Telegraph Magazine. It is a journey that he will repeat at least once a week over a period of a year.

Fast forward 30 years to the present, and the same Martin Parr is sitting in the back room of the foundation he opened in his own name five years ago, leafing through a newly printed photobook of those images from Chew Stoke. He’s got a freshly minted CBE, hand presented by a lady with a sword just the day before, sitting on the shelf next to his Russian space dog souvenirs, and the place is bustling with staff working on everything from the exhibition program to packing up prints for shows in London, Paris and beyond, and sending out books from his bookstore.

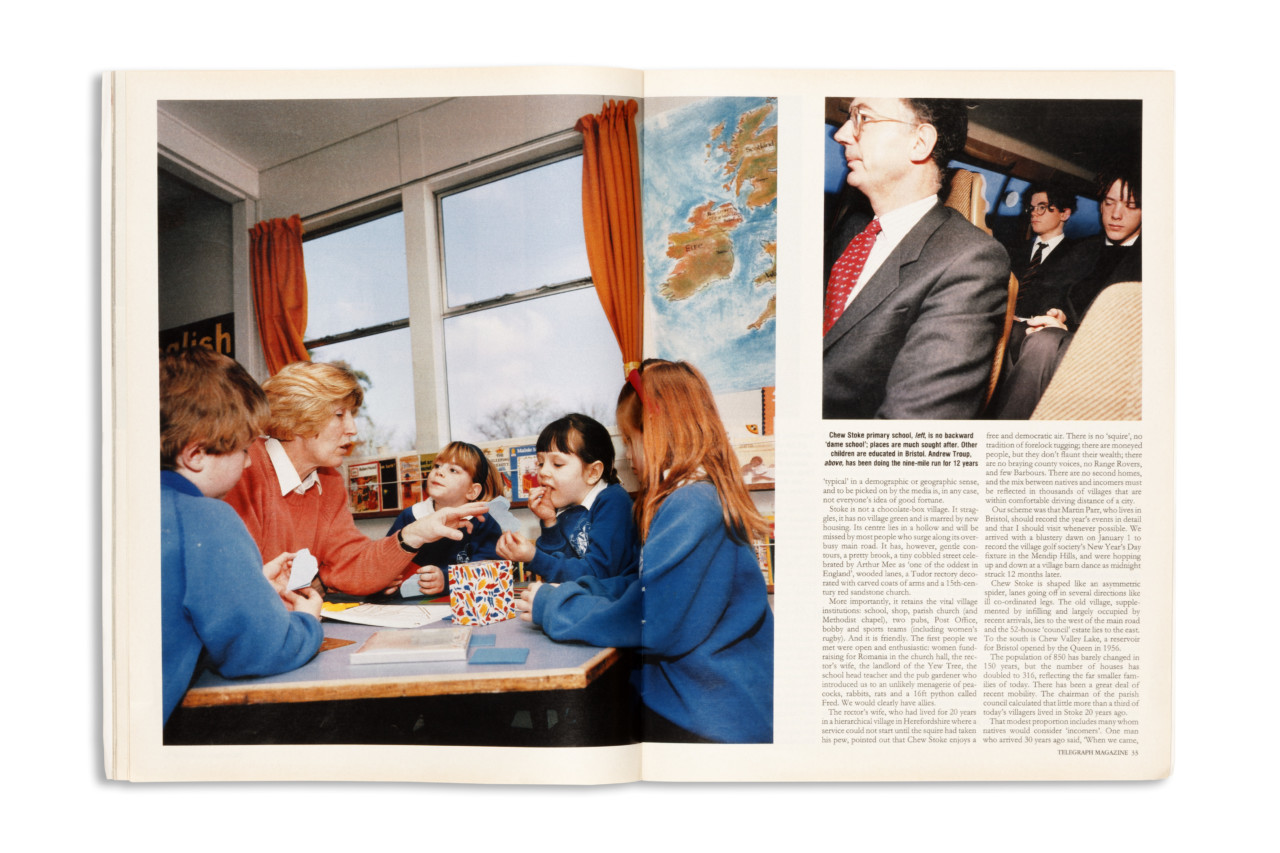

“It was basically a magazine commission,” confirms Parr, “but it was the most intense one I’ve ever done. We photographed during 1992, and in February 1993 it was published across 16 pages in the Telegraph Magazine. Today, if you have four pages, you think you’re in for a big spread. They paid £12,000 for this commission. It’s a good example of how the magazine landscape has changed entirely. If you get £500 from any of these magazines now you think you’re lucky.

The idea to photograph there came on the back of a book published in the late 1940s titled Exmoor Village made by John Hinde, the now celebrated postcard photographer whose work Parr helped bring to greater prominence through an exhibition he co-curated for the Irish Museum of Modern Art a year earlier.

“We thought, ‘Let’s look at that village and see what’s happened since.’ We checked it out and it turned out it was a National Trust village, so nothing had changed,” Parr recalls. “So we thought, let’s find a village near Bristol that I can get to very easily. We looked around for a village that had a shop, a pub, a post office and a school, and Chew Stoke ticked all the boxes and felt like the right place..”

These key village locations are the heart of the book, which is a visual essay both on a particular idea of rural Englishness and the sites of a community and the ways in which they tie the village together. The book opens at the start of the day with the milkman on his rounds and ends with a New Year’s Eve barn dance in the village hall, an awkward-looking middle-aged couple preparing to kiss, eyes half-closed, as the clock strikes midnight.

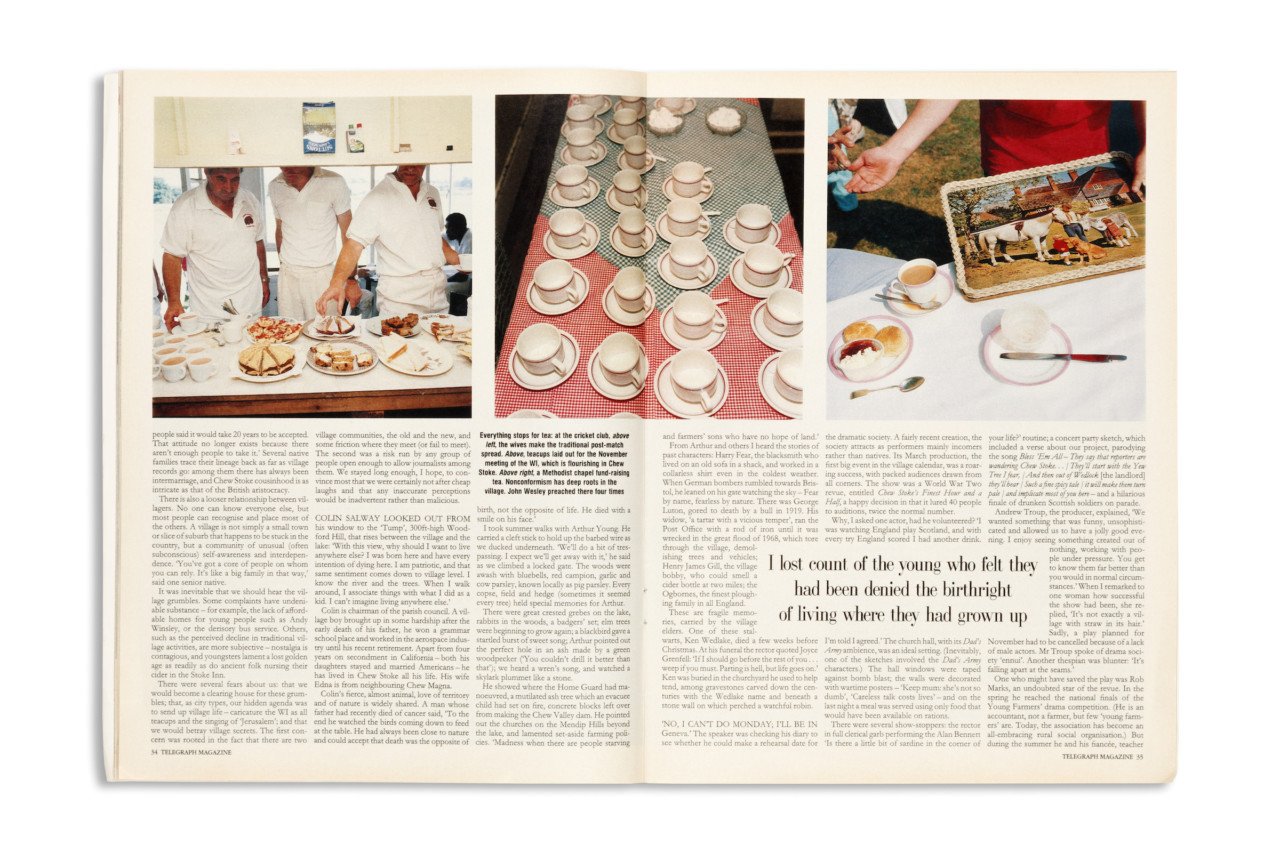

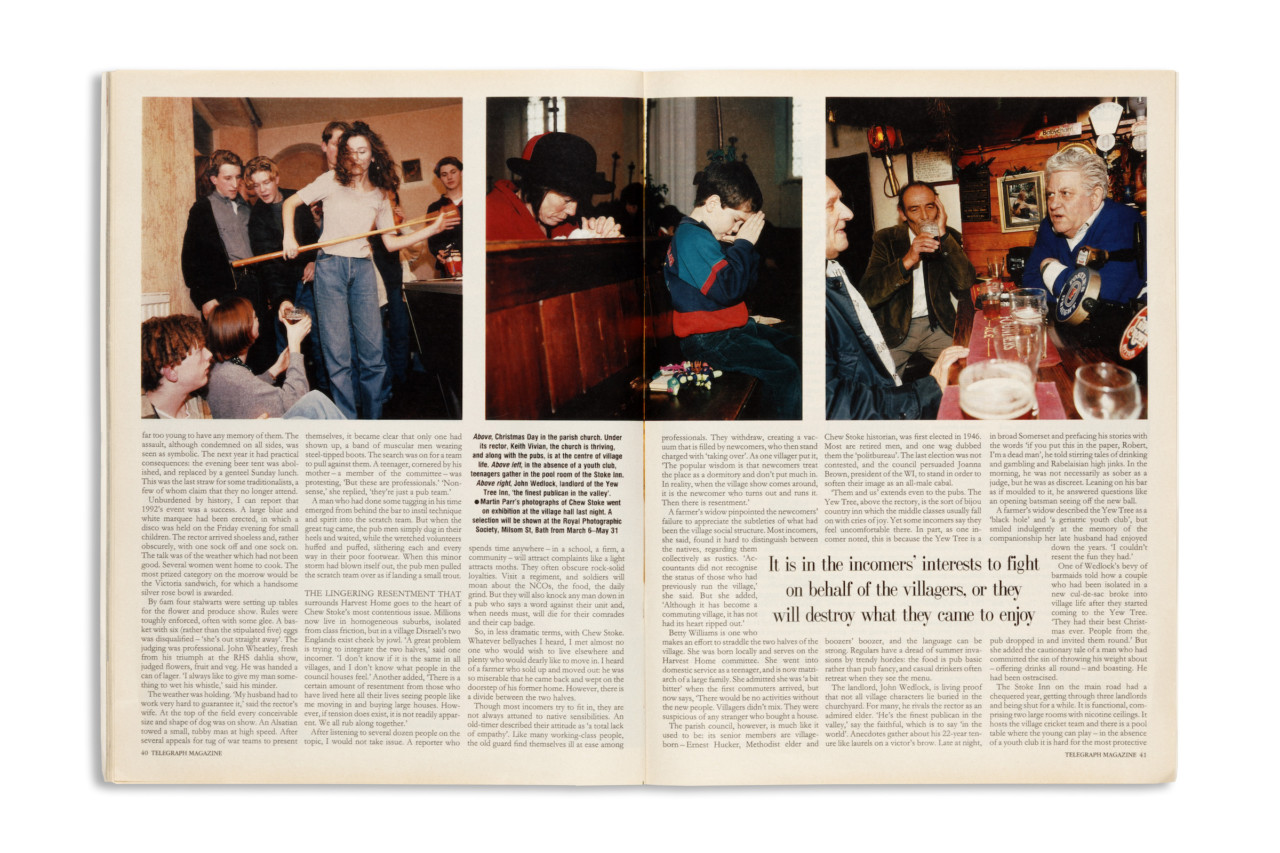

There are photographs of cricket matches, jumble sales, cream teas and keep-fit classes. Parr hones in on the details of everyday life; a vast blue enamel teapots serving up proper English tea; an idealized rural family scene printed onto a tray framed by a whicker border (top); a jar of prize-winning lemon curd; a meat raffle. Cricketers search for lost balls in the undergrowth. Pumpkins are weighed in the Harvest Home festival. Cider is drunk in the (now closed) Yew Tree Inn. And villagers search for bargains at the jumble sale.

"In 1992, it was proper tea from a proper teapot – these small details are obviously important."

-

“We met key people like Keith Vivian, the vicar, who was extremely helpful, and he introduced us to the stalwarts of the village,” says Parr. “And we met people through the events we went to. The village hall had a Women’s Institute, it had a keep fit, so by the end of the year most of the people in Chew Stoke knew who we were and we could get access to anywhere we wanted.

“We got permission to go into the school and photograph the kids. To get in a school now, can you imagine?” So there are images of school dinners, and a primary school ‘Computer Base’ that is something from the digital stone age.

There is picture of a man eating hot-buttered toast in a living room below a leopard cub wall hanging staring down from flock-papered walls. There is a picture of a family inspecting a new-build show home, its ruchéd curtains, apricot striped sofa and aspirational chess set dating it in true Martin Parr style.

While all seems to be well on the surface, the show home hints at an increasing divide in the village. “The big problem of course was people from the village not being able to afford to live there. They have to live in Bristol and commute down. And the people who could afford to live there were commuting into Bristol either to deliver their kids to their private school or to go to their job as an accountant or solicitor or whatever it was they were doing. There is that two-way traffic. It has become more and more of a commuter village. Very few people earn a living in the village itself.”

That change has been exacerbated by increasing house prices. When Parr photographed, the UK’s febrile housing market was in its last major downturn. Since 1992, with the exception of a blip following the economic crisis of 2008, prices have gone inexorably up, so that today the average price of a house in Chew Stoke is an eye-watering £745,000.

Aside from an increase in house prices and the resulting change in the population, little else has changed. “The farm is still there,” says Parr. “A big health practice that serves the whole of Chew Valley has been built, so that’s positive. There’s a café there, but the shop has closed – and the shop was an essential ingredient of the community. One of the pubs, the best one [the Yew Tree] closed. They don’t do cream teas at the Methodist chapel in August. When you go to one of these places now you don’t get tea in a ceramic cup, you get a paper cup with a tea bag in. In 1992, it was proper tea from a proper teapot – these small details are obviously important.”

Most importantly, the village hall is still there, and to commemorate the 30-year anniversary of the project, Parr returned last month. “We had a huge party that Friday night. We tried to do an exhibition again [a repeat of the show there in 1993] but they said we can’t use blu-tack to stick pictures on the wall so we did a slide show instead.” The slide show became both an exercise in memory and nostalgia, but also a kind of memorial. “When you look through the pictures and you see someone very old, you know they are dead,” says Parr. “I find that very strange. At the slideshow, there was no shyness about saying who was alive and who was dead.”

The images from Chew Stoke distill a golden era in Parr’s photography, shot the same year Signs of the Times went out on British television, and wedged between The Cost of Living and Small World.

“It was never intended to be a book. That was Rudi’s (Thoemmes of RRB Books) idea. And there’s a French edition as well. The people in Chew Stoke couldn’t believe that. When I told them I was more popular in France than in England they couldn’t understand that. It’s a difficult thing to explain really.

“I guess it’s just that the French love photography, they take photography seriously. All the main papers there have a dedicated photography reviewer or critic. If I do a show in Paris, it’ll be reviewed by all the papers. If I do a show in London, I might get something in The Telegraph. For example, when I did a show at the National Portrait Gallery in 2019, not one of the broadsheets came. They are not interested because their main reviewers are art reviewers and they’re not interested in photography. It’s the difference between the two countries. They don’t trust photography here. They still think it’s not that serious.

“My bigger project is documenting life in the UK in my 50 year period of being a photographer, particularly how people go about their leisure pursuits. Chew Stoke fits into that. To look at what’s going on in one village and photograph it quite carefully and intensely – I’m proud to add that into my archive of what I’ve photographed in the UK. I think it’s an important addition to this archive that I leave as part of my legacy, as well as this institution [the Martin Parr Foundation] of course.”

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Shop the Martin Parr collection here.