Bob Dylan and the Magnum Archive

The music legend's latest promo video draws on the Magnum archive using a sequence of 79 photographs to evoke a sense of hope emerging from bleakness.

Bob Dylan has unveiled a short film featuring 79 photographs from the Magnum archive.

Made to accompany a previously unreleased version of his classic 1997 track, Not Dark Yet, the new Dylan video arrives ahead of the latest instalment of his ‘Bootleg’ series of rare and previously unheard recordings.

Featuring images by three generations of Magnum photographers, including Eve Arnold, Eli Reed, Paolo Pellegrin and Jonas Bendiksen, the video was put together by Clemens Habicht, a freelance designer and director, and Josh Cheuse, Communications Creative Director at Sony Music Entertainment.

The latter (who is himself a photographer, best known for his images of Joe Strummer), is a music industry veteran, having worked on “literally hundreds of covers and campaigns” for artists as diverse as Tony Bennett, AC/DC, David Bowie and John Coltrane. So, has he learnt to take a different approach when it comes to presenting archive material from a music legend such as Dylan, as compared to working with a younger artist on new material?

“I always just try and approach every project in a creative way that pushes the boundaries whenever possible,” says Cheuse. “For this project, I wanted to create a kind of installation piece.” He says that the draw of working with Magnum is that it is “legendary like the music itself,” adding that the agency is a first call when trying to find images “that embody the commitment of our artists and our company.”

The relationship between Dylan and Magnum stretches back to early days of the singer-songwriter’s career. W. Eugene Smith and Danny Lyon made notable photographs of him in the mid-1960s. And, of course, there’s Elliott Landy, whose archive is represented by Magnum. He took many of the most intimate and iconic images anyone has ever seen of Dylan, beginning with a 1968 shoot at his home in Woodstock in upstate New York.

More recently, in 2005, the producers of No Direction Home, the Martin Scorsese directed documentary that covered Dylan’s life up to 1966, when he had his infamous motorcycle accident, drew extensively on the Magnum archive. And Cheuse has been working on projects with the agency for more than a dozen years.

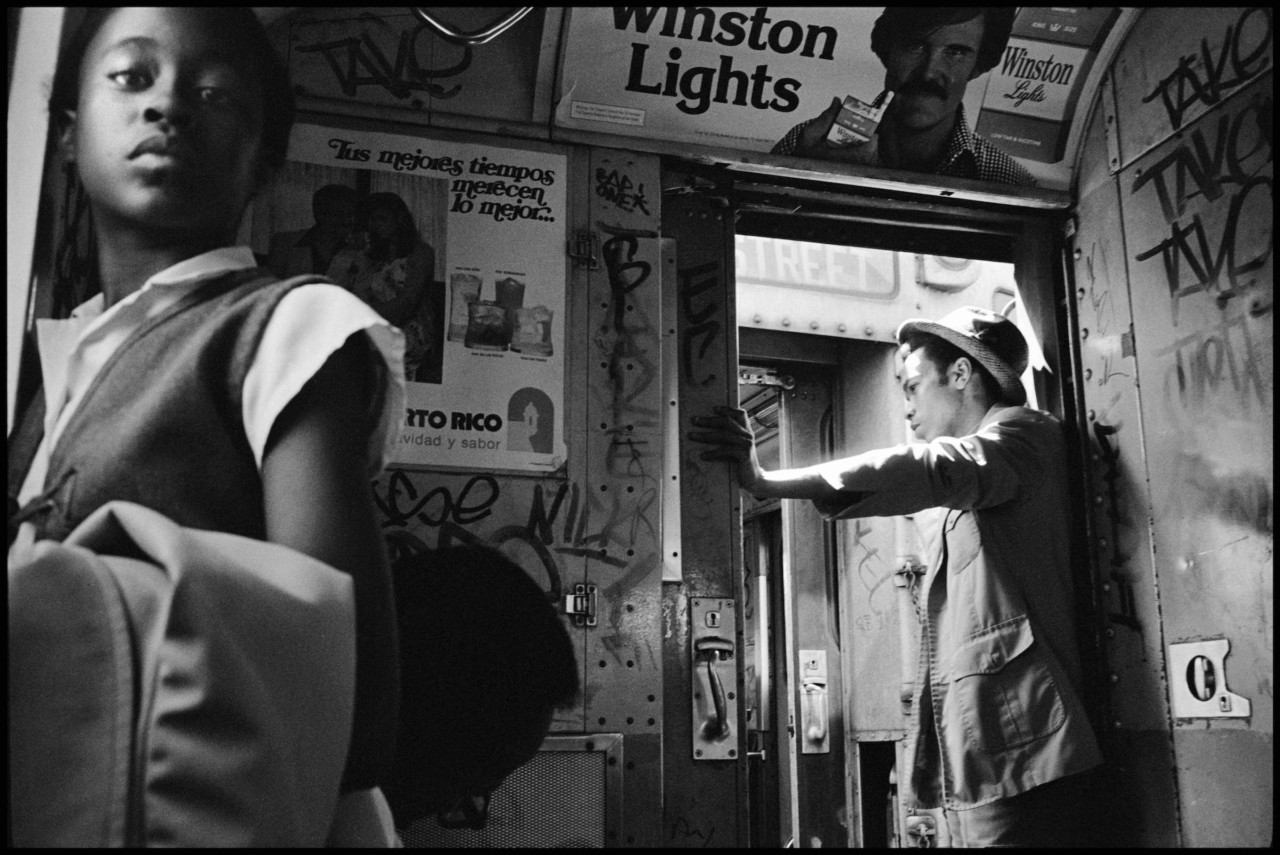

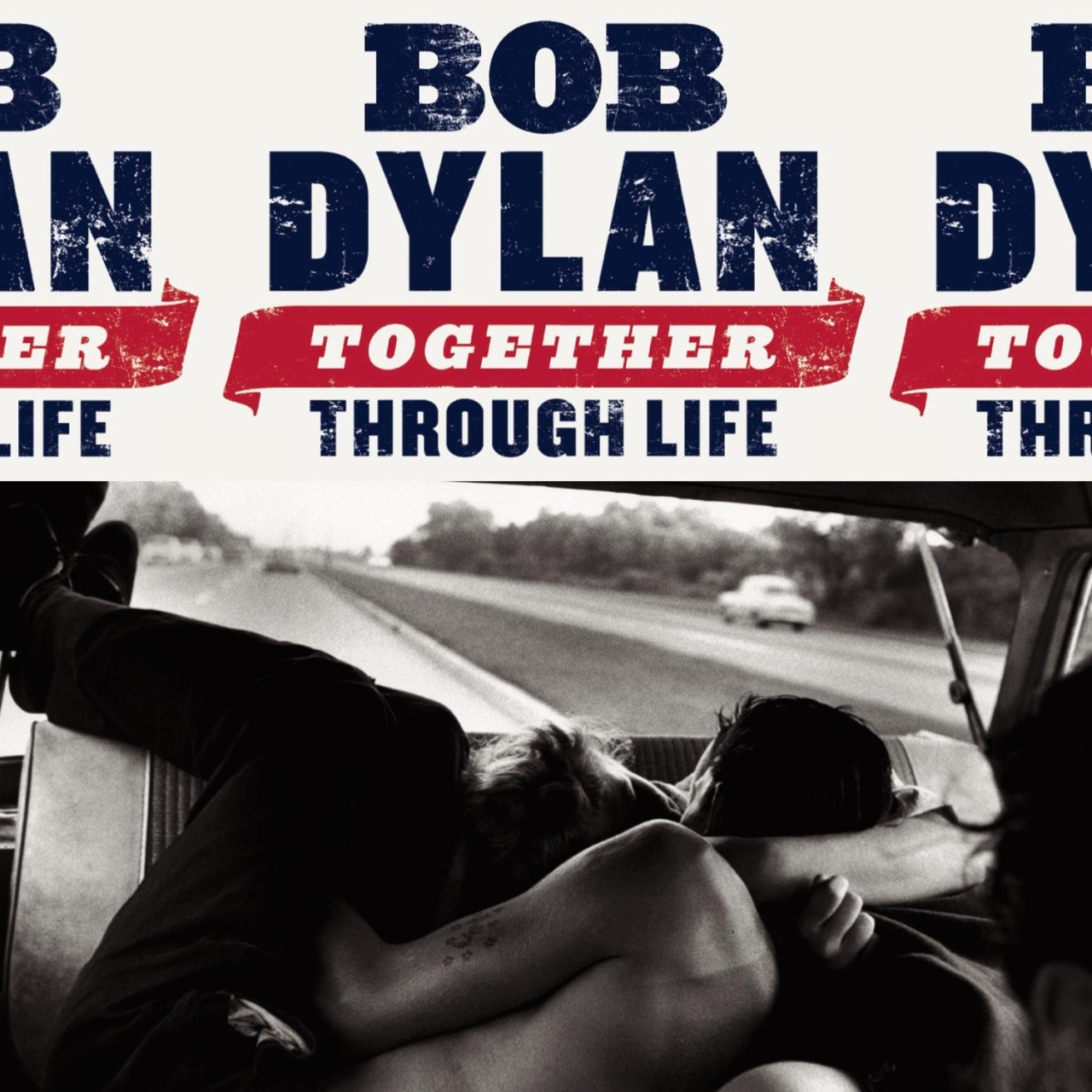

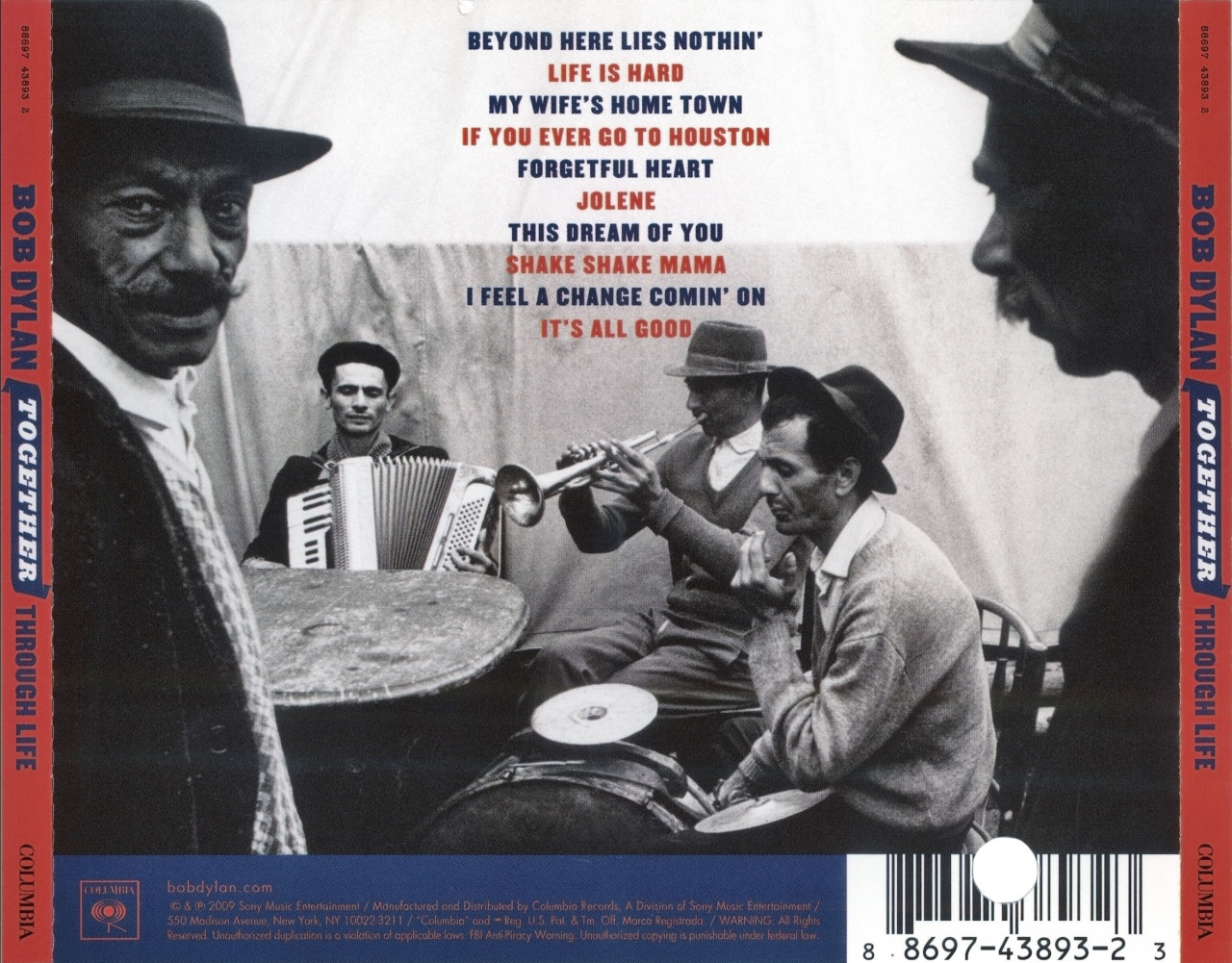

“We had worked with Magnum most recently on Bob Dylan’s Rough and Rowdy Ways album package that used an Ian Berry image on the cover. Before that we had used a Bruce Davidson image on the cover of Together Through Life, designed by Coco Shinomiya, which also had a Josef Koudelka image on the back cover. I put together the subsequent music video for Beyond Here Lies Nothin’ from that album, using more images from Davidson’s Brooklyn Gangs series.”

Aiming “to produce a film that speaks of the passing of time, our place in history and the human connection that defines our lives,” this latest collaboration is in part a promo for Dylan’s upcoming Bootleg Series Vol. 17: Fragments – The Time Out Of Mind Sessions (1996-1997), put out by Sony Legacy later this month. Anthony Burrill, a graphic artist known for his love of monochrome and vintage analogue design, provides the bold typography. Meanwhile, Cheuse selected images from an edit of 399 pulled together by Michael Shulman, Magnum’s Senior Licensing Manager based in New York City.

It’s no coincidence that Shulman is also a huge admirer of Dylan and his music, and over the years has built a relationship with his management and record label. “I’m a massive fan since I was a child, and he’s been a constant inspiration to me,” he says.

The promo for Not Dark Yet provided an interesting challenge. It was recorded by Dylan in January 1997, and released as a single later that year, also appearing on the album Time Out of Mind, which went on to win a Grammy. This newly unearthed version is a session recording. “He often tries out different arrangements, lyrics, music and musicians before deciding on the final released version,” explains Shulman.

“It’s a beautiful song, covered by many, but the original is the best, in my opinion. The new version is a completely different arrangement and has many lyric differences. It is more rocking, almost like the Rolling Stones.

"The mood is weary, late night, almost – but not quite – defeated."

-

“It can be interpreted in many ways, like most of his songs. In the original, the mood is weary, late night, almost – but not quite – defeated. The tag line is, ‘It’s not dark yet, but it’s getting there.’

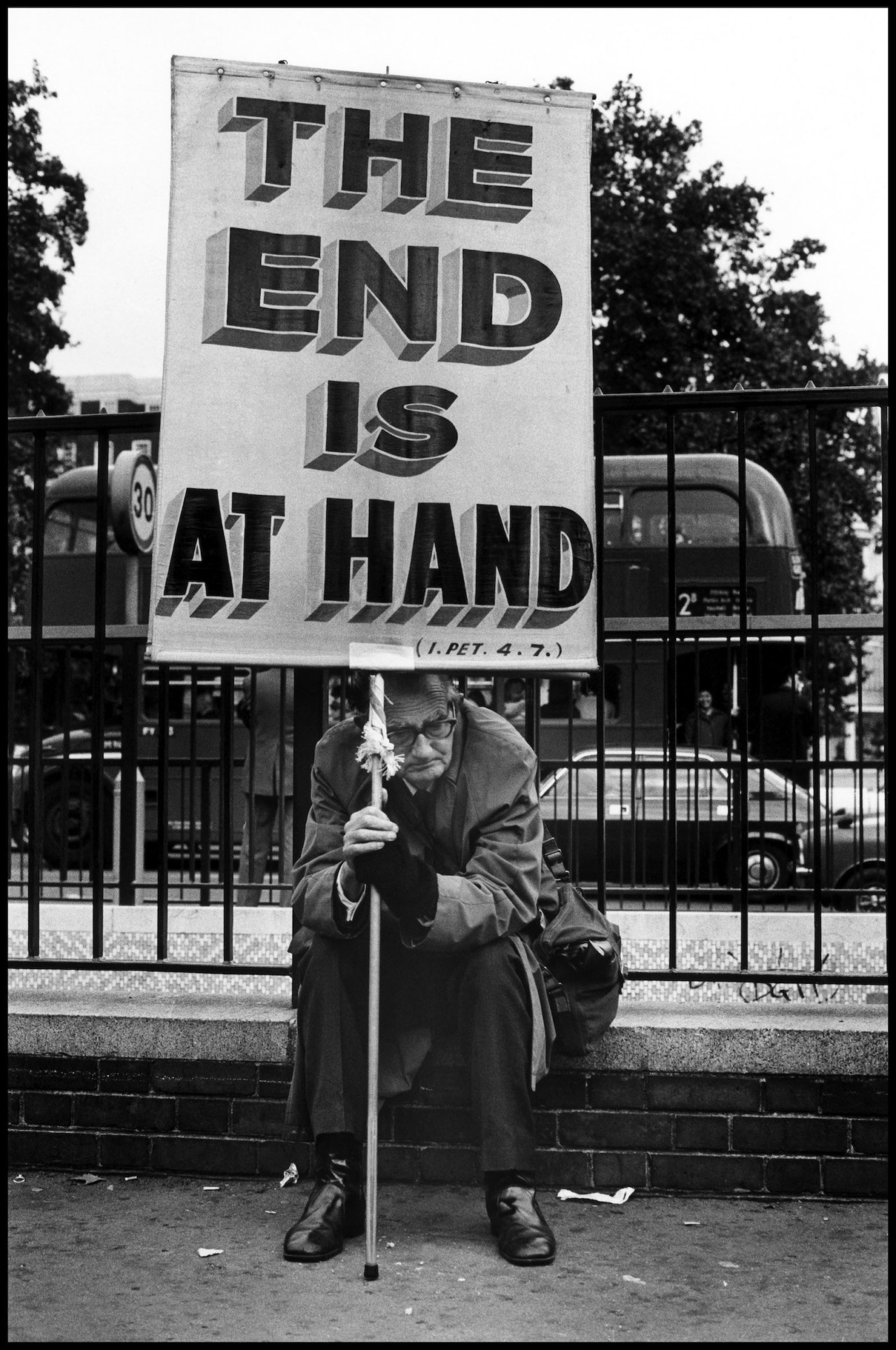

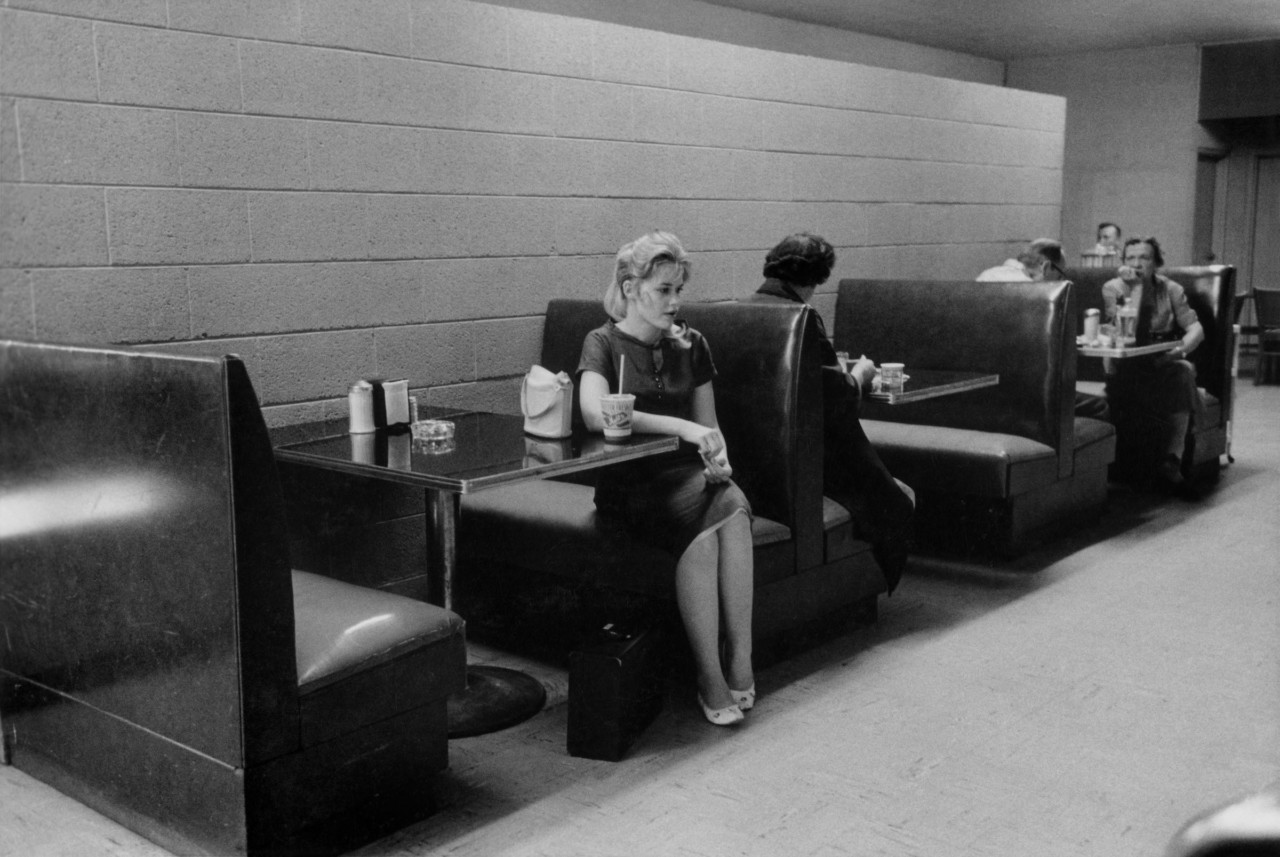

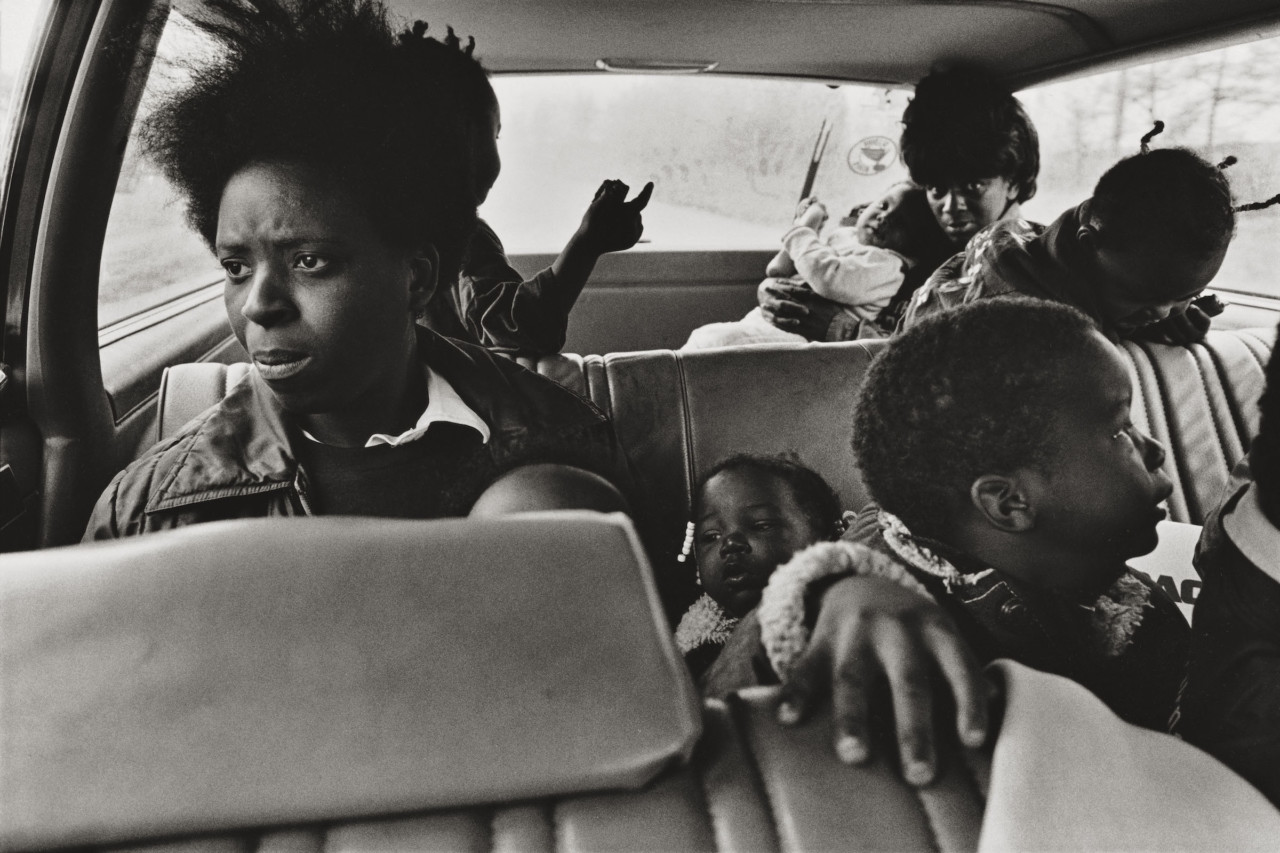

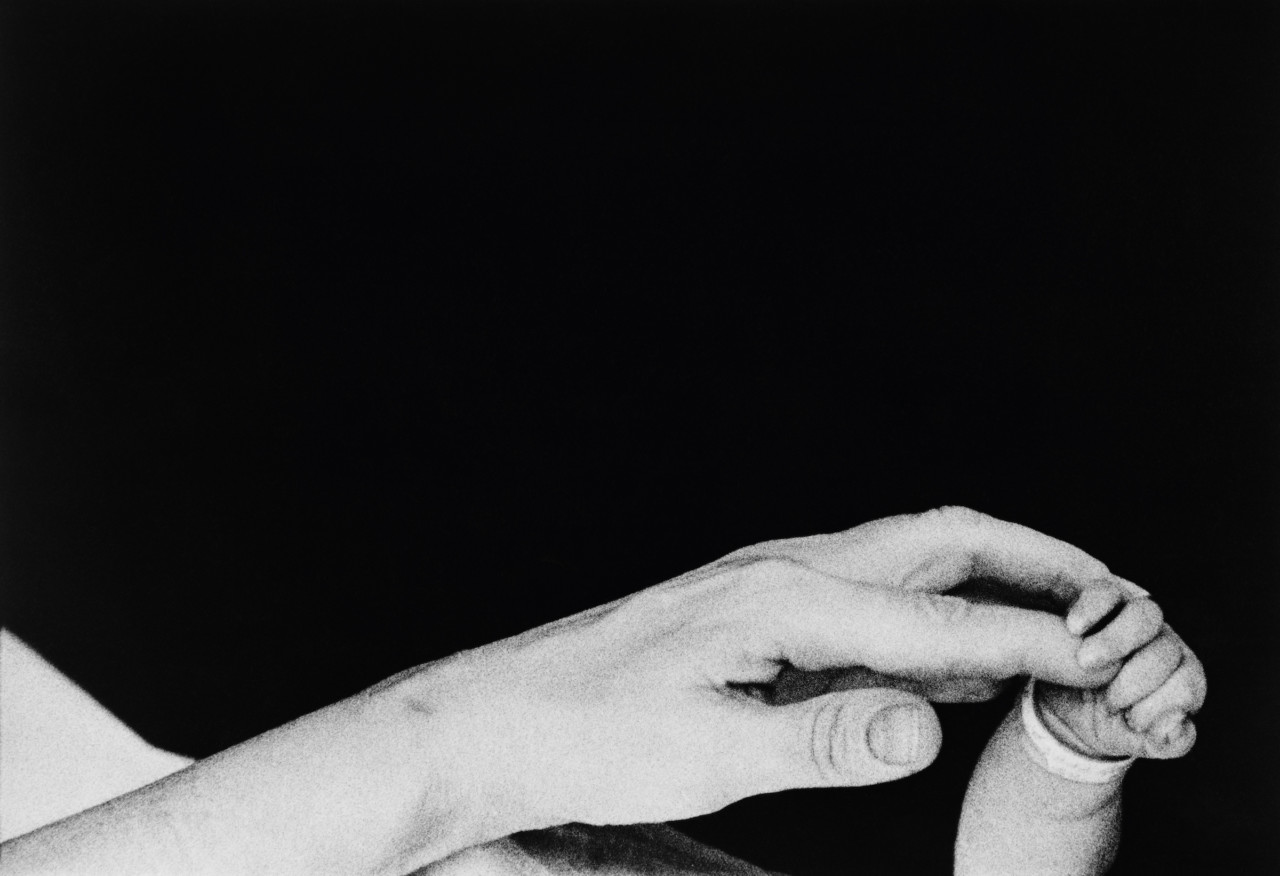

“So, I looked for pictures that showed people lost in thought, isolated, going through some inner turmoil, unaware of the camera. Josh suggested that I balance the mood with more hopeful images, so I went and found so many great photos of children being deliriously and unselfconsciously happy, starting with Wayne Miller’s work, which I dearly love. There are also Ian Berry’s brothers reuniting at the Berlin Wall, and Burt Glinn’s people at the Berlin Wall waving to their family or friends on the East side. Just pure joy.”

When it came to making the final selection, what were Cheuse’s guiding principles? “To find images that worked with the track in all its layers of meaning,” he replies. “Michael Shulman really helped hone in on images that worked, together with little nudges from me – images that were evocative but still left room for the listener to attach their own meaning.”

What were the emotions that he hoped the video would evoke? “Love. Dreams. And hope – the very words that Anthony Burrill set in metal type in a little printers shop in Rye on the English coast, the same way they’ve been doing it for hundreds of years. So we juxtapose those words with the Magnum images, and voila!

“Then Clemens Habicht worked his magic. He’s the master of puzzles, and every project is a kind of puzzle. I was in London, he was in Paris. I described the project to him and a day later he appeared at my front door.”

With the images and typography already in place, “my role was to figure out how that becomes a music video,” says Habicht. “The Magnum archive was one of the reasons I was so excited to be invited; working with these profound images was like spending time with my heroes. Each photographer has dedicated their lives to capture something essentially true to them, which I think can be said about Dylan’s remarkable music.

“Each photo has its own history and story in time, and I gravitated towards images that were less depictions of events so much as the effect these events had on the people in the photographs.

“I was also very conscious of allowing the images to exist as photos, to not interfere with visual effects, to allow them to affect the viewer,” Habicht continues. “The edit process is far more controlling than, say, curating an exhibition or publishing a book, as you dictate how long someone can spend with each image, when and how they move from one image to the next. These transitions between images became shots in themselves, creating contrast by juxtaposing extreme emotional states that can be present at the same time.

“The song sits in a place of bleakness, and yet out of this emerges a feeling of hope. I was looking to find evidence of this contradiction of the human spirit; photographs that do not shy away from looking directly into the pain that exists in the world, and the strength and defiance to see also the beauty in those moments.”