Like a Blood Stain on a Handkerchief

A text by Thomas Dworzak and writer Petr Trotsenko about Kazakhstan’s northern border for the Beyond the Silence project.

During the European colonialist expansion, the empires of France, Great Britain, Germany, and others mostly drew brutal, straight lines, chopping out territories and dividing countries on other continents. Russian imperial expansion gradually colonized its neighbors, taking over territories and thus creating fizzled-out borderlands, more like a bloodstain on a handkerchief.

I grew up at the end of the Cold War in 1980s rural Bavaria, right at the Iron Curtain, 7 kilometers from the German-Czechoslovak border — the end of the world.

Starting as a photographer, I moved to Moscow at the beginning of the 1990s. In the naive honeymoon of post-Soviet enthusiasm, one of the first cracks I remember was chauvinistic Russian talk questioning Kazakhstan’s right to exist from the likes of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Eduard Limonov, and Vladimir Zhirinovsky. I spent the following two decades covering the brutal Russian wars in the Caucasus — Chechnya and Georgia.

After the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, I started documenting what could be considered a new Iron Curtain—a few hundred kilometers east of the old one.

Going down from northern Norway, Finland, the Baltics, Poland, and south through the Balkans, the line is fairly straight and well-defined. In the Caucasus and Central Asia, alliances and identities become more ambiguous and confusing; towards China, the line somehow fades out.

For the Beyond the Silence project, I chose to travel along Kazakhstan’s northern border with Russia.

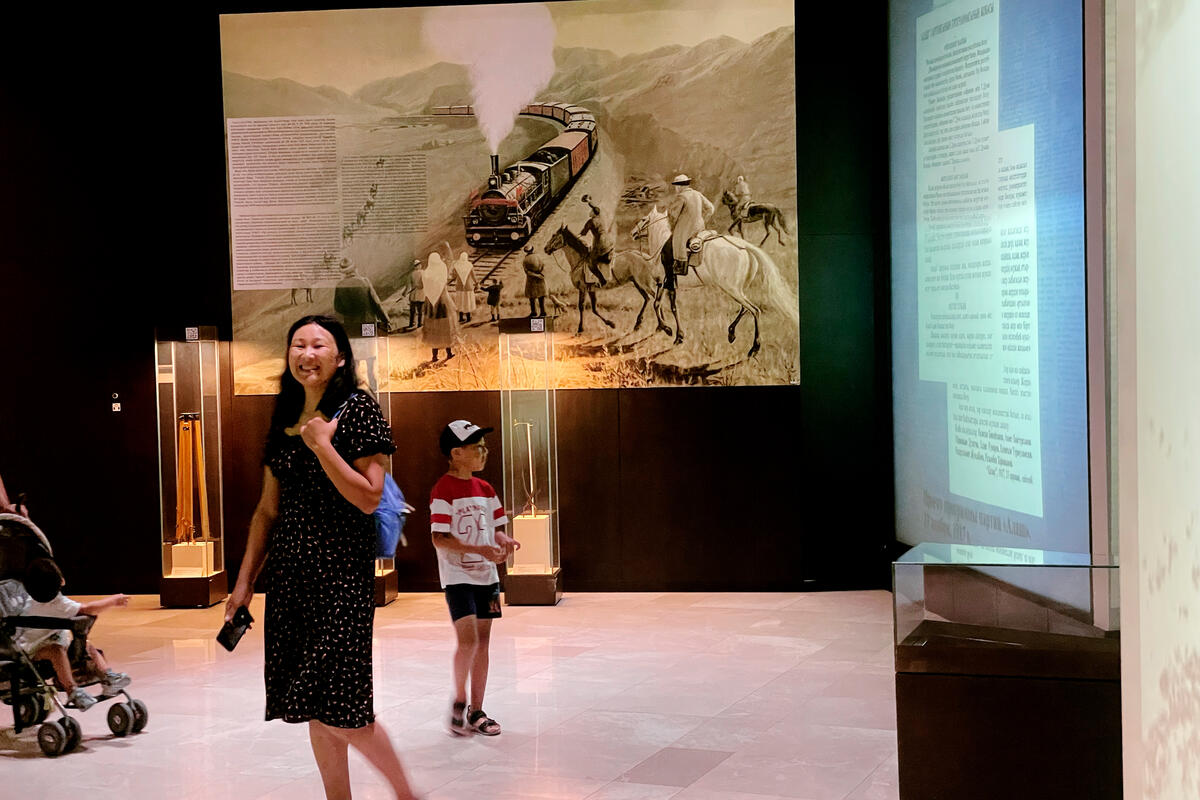

Starting in Astana, the new capital, which was moved further north, also in an attempt to balance the country, I wanted to look at the impact of colonial and Soviet history, its representation and current life among the significant Russian-Slavic population in the North and get a sense of their identity. I traveled along a crescent from Oral (Uralsk) to Kostanay to Petropavl (Petropavlovsk) to Pavlodar to Semey (Semi Palatinsk) along the world’s longest land border, which totals more than 7000 kilometers

I sometimes felt like I was in a Russian Siberian city. In many places, all I heard was Russian, spoken by all nationalities. I looked for signs of Moscow’s shadow, influence, revendications, and claims. In many parts, most people had Slavic features. However, the block of ethnic Slavs is not homogenous. Around half a million Ukrainians were deported first by Czarist Russia, then by the Soviets. The same is true for the small Polish community. Over half a million ethnic Germans have left northern Kazakhstan to be colloquially considered “Russians” in Germany. The officially celebrated multinational cohabitation of “130 nationalities” was often the result of entire peoples being deported by Stalin. Remnants and memorials of Gulags are ubiquitous. At the same time, the memory of the heroic “Great Fatherland War,” World War II and nostalgia for the glorious days of the Soviet Union are omnipresent.

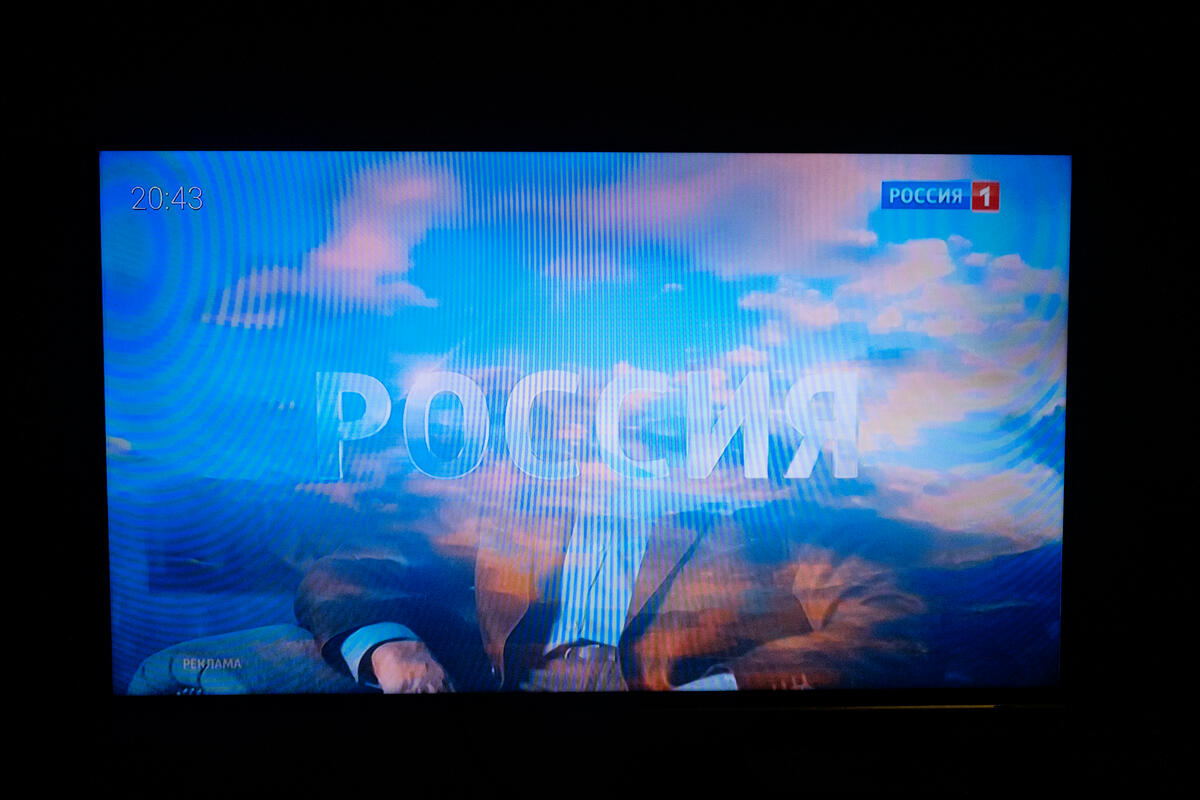

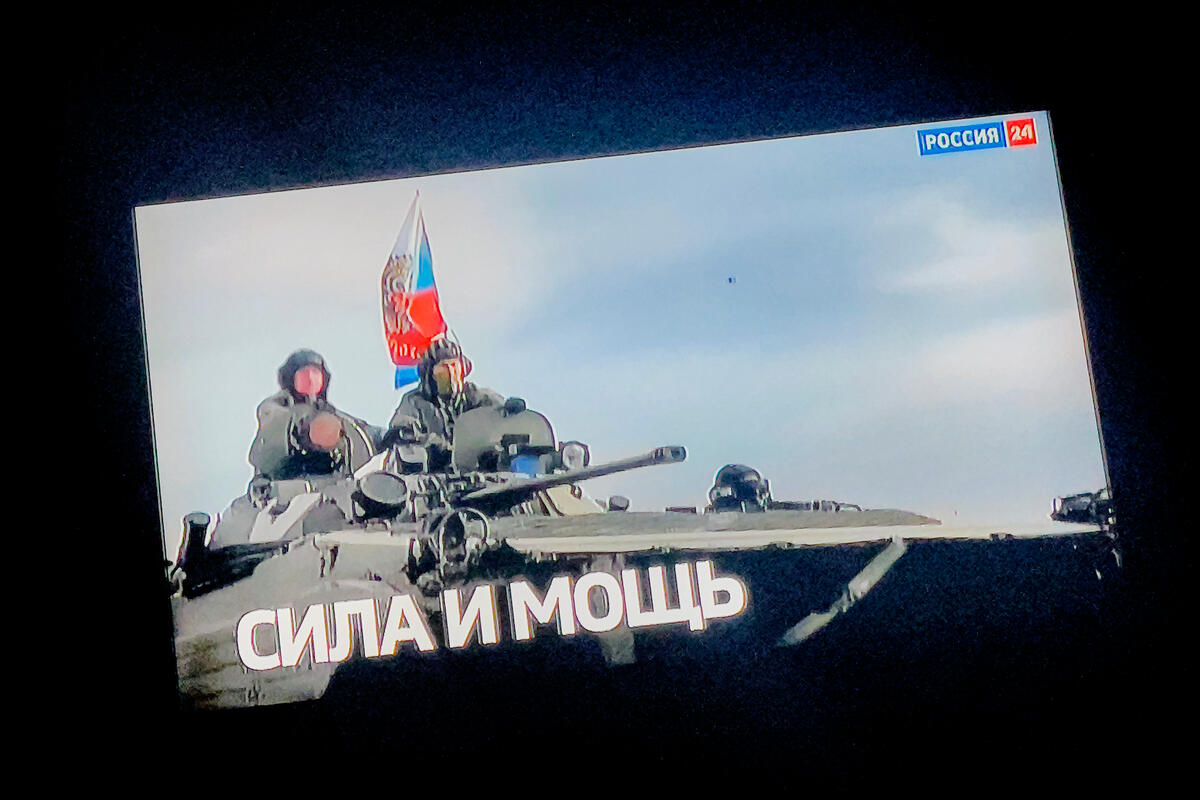

Fairly common celebrations of “Ukrainianness,” from what I saw, were highly unpolitical and in a purely folkloristic way — no mention of the war whatsoever. Any potentially difficult issues were drowned in relentless song and dance. Wherever I stayed, Russian-state TV satellite dishes pumped the anti-Western, anti-US, anti-Ukrainian Kremlin line relentlessly into people’s homes.

This language and rhetoric clearly influence Russian speakers. The Kremlin considers them subjects of its special protection, and the area is clearly part of the “Russian World” doctrine. I can’t judge from the often confusing and contradictory bits of impressions and conversations where people ultimately see themselves, and the future will show if this is similar to what happened in Donbas before 2014.

My friend and colleague Petr Trotsenko, a journalist, photographer and writer of Kazakh citizenship with Ukrainian ancestry who grew up near Oral (Uralsk), was invaluable as a guide and companion during my travels through these borderlands. He sketched down some of our encounters and conversations.

Northern Sketches

Written by Petr Trotsenko (translated from Russian)

Sketch One:

Felix Bayukansky is a well-known Oral entertainment organizer and the head of the local Jewish community. During a concert of Oral Cossacks, Bayukansky congratulated those gathered and recalled how, in 1990, he organized a Cossack assembly and held elections for the first ataman. There have never been any Jewish pogroms in Oral, but not because people have always lived here in peace and harmony; it’s just that there were very few Jews in the city, and they rarely crossed paths with the Cossacks in everyday life. Before the revolution, Oral even had a small synagogue, which was destroyed during the Soviet era.

Sketch Two:

The community of ethnic Ukrainians in Oral holds a Ukrainian cultural festival, Sorochyntsi Fair, every fall. The festival is fun: dancing, singing, and treats. But at the festival, you can’t hear a word about the war in Ukraine, and it’s hard to find even one Ukrainian flag (except for a small flag on a table with Ukrainian dishes).

The main organizers of the holiday are the local authorities, who are afraid of any political statements and try not to notice any external and internal problems. If it is a holiday, then everything should be cheerful.

Sketch Three:

At Sorochyntsi Fair, one woman, an ethnic Ukrainian, said, “Ukrainians and Russians are one people, and the war is because of the Banderites, who want to break away from Russia.”

“But Ukrainians have their own language and culture. Why are they and Russians the same people?” I asked the woman.

“Because we have a common history and Kyivan Rus, from which we all came,” the woman answers. “I speak Ukrainian, but I do not communicate with my relatives in Ukraine; they are Banderites.”

She added that her children have been living in Russia for a long time because, in Kazakhstan, they feel like second-class citizens: here in Kazakhstan, they are forced to learn the Kazakh language and speak Russian less and less.

Sketch Four:

During speeches at national holidays, officials like to talk about friendship between peoples and constantly note that representatives of 124 ethnic groups live peacefully in Kazakhstan. At the same time, they never remember that Chechens, Poles, Ukrainians, Koreans, Jews, Armenians, Greeks and many other peoples were deported to Kazakhstan during Stalin’s mass repressions, and they do not remember the thousands of older people and children who died. Kazakh officials remember the mass repressions only once a year — on May 31, when the country officially observes mourning in memory of the people repressed and who died of hunger during the Soviet era.

Sketch Five:

In Oral, we met Maksut Utepov, a Kazakh in a Cossack uniform and with medals. He said that his ancestors were Muslim Cossacks, and he wears the uniform in tribute to the memory of his great-grandfather, a nomad from the Nogai tribe who served in the Cossack army. In the 19th century, to become a Cossack, it was not necessary to convert to Orthodoxy; you just had to follow the Cossack laws and, if required, fight for the interests of Russia.

Sketch Six:

Dolmatovo is the northernmost village in Kazakhstan. It is located 70 kilometers from Petropavlovsk, a city with more Russians than Kazakhs. The taxi driver who takes us to Dolmatovo is an older man with an old army tattoo. On the rearview mirror is a St. George ribbon — a Russian symbol of victory in World War II. At the same time, Ukrainian music is playing in the car the whole way. The man says he is Russian but loves Ukrainian music and the Ukrainian language very much because “the language is very beautiful, and the music is very cheerful.” He does not talk about the war and does not understand politics, but in conversation, he calls Crimea Russian.

Sketch Seven:

The village of Fyodorovka, Kostanay region. The border with Russia is less than 100 kilometers from here. Many Russians and Ukrainians are in the village — descendants of those who came here in the 50s and 60s of the last century to the Virgin Lands. Valentina Ivanovna is an older woman whom we met in the local park. She says she was born in Ukraine — in Lugansk, but has lived in Kazakhstan since early childhood and considers it her homeland. Her parents came here, and her children and grandchildren have long lived in Russia. The son works as a captain of a river ship, and the daughter is raising the children alone since her son-in-law, a participant in the war in Chechnya, went to the front again, this time to fight against Ukraine. “He went to the ‘SVO’ and did not tell anyone about it or even warn his wife, the bastard!” the woman swears. “People should not fight: if you go to war once, you will be drawn there all your life.”

Sketch Eight:

Monuments to the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin and the Kazakh poet Abai Kunanbayev can be found in every city in Kazakhstan. Abai is the most famous poet in Kazakhstan, just as Pushkin is the main poet in Russia. Abai was much younger than Pushkin — he was born in 1845 and died in 1904, but the poets are often depicted together to emphasize the cultural connection between the Kazakhs and Russians. In Petropavel, there is even a monument where the two poets are represented together as if they had known each other for a long time. Some people who do not understand Kazakh literature and culture think that the poets were friends and that Pushkin came to visit Abai.

Sketch Nine:

There is a very interesting police museum in Petropavel. It is housed in several small rooms, where a variety of exhibits are kept, from homemade samurai swords and crossbows to rare antique pistols, which criminals used to rob city residents during the Soviet years.

The museum’s caretaker, an older woman and retired colonel, begins her tour with the history of the czarist soldiers who kept order 300 years ago. She recalls with nostalgia the Soviet times, when there was more order and criminals were punished severely, even with the death penalty.

“Almost all Russians used to serve in the police, but now there are more Kazakhs,” the woman adds, and her voice is filled with notes of nostalgia for the times when there were more Russians.

Sketch Ten:

The small village of Ozernoye appeared in the late 1930s, when, by Stalin’s order, Poles from western Ukraine were deported to Kazakhstan. Catholic Poles believe that the Virgin Mary saved them in this place because the lake near which they settled turned out to be full of fish, which saved people from starvation. In memory of the “miraculous” rescue, a church and a hotel for Catholic pilgrims were built in Ozernoye, where they come every summer.

The local older people are descendants of deported Poles; they go to church and speak Polish to each other. We met two elderly Poles. One was born in Kazakhstan, the other came from Ukraine almost 50 years ago and stayed here forever.

“I was born in Kazakhstan, but I am Polish!” says the first man.

“If you were born in Kazakhstan, then you are Kazakh!” jokes the second.

The older men do not want to go to Poland, their historical homeland. “I have been to Poland several times, but I cannot stay there for more than a week, so I want to return to Kazakhstan. This is my homeland.”

Sketch Eleven:

Kazakhs do not like Russian military symbols and consider them a symbol of “new fascism” and Russia’s aggressive military policy against neighboring countries. They remember Russian colonization, Stalin’s repressions, and famine well. Therefore, if someone in Kazakhstan accidentally notices a sticker with the letter Z on a car, they immediately call the police or demand that the driver erase the inscription.

Such an incident recently occurred in Oral, when a Kazakh blogger forced a Russian citizen, also a Kazakh, to erase the letter Z from his car and filmed the entire process. The video became popular on social networks and reached pro-Kremlin Telegram channels, where they were outraged by the actions of the Kazakh blogger. According to Russian propagandists, the letter Z symbolizes patriotism, not aggressive military policy.

Sketch Twelve:

In the northern regions of Kazakhstan, the influence of Kremlin propaganda is felt: people visit Russia more often and watch Russian television, which is easily broadcast in Kazakhstan. For these reasons, many support Russia and believe that the Nationalists and the Banderites live in Ukraine. Some Kazakhs, and not only ethnic Russians but also pro-Russian Kazakhs, sign contracts with the Russian army and go to war. They do not plan to return to their homeland: according to Kazakh law, Kazakh citizens’ participation in another country’s military actions is punishable by imprisonment. “My brother went to the SVO in January last year,” says Mikhail, a 34-year-old resident of Petropavlovsk. “He had Kazakh citizenship but lived and worked in Novosibirsk for the last three years. My brother discussed his decision with his wife, who supported him and went to war. We stopped communicating because of this, but as far as I know, he is alive and continues to fight. I think that he went to war not because of the money because he had a good job, but because of the propaganda that caused him to become a victim.

Sketch Thirteen:

In northern Kazakhstan, a village called Peterfeld was founded by Germans who moved from the Volga in the early 20th century. During the Soviet years, there was a collective farm here, which was considered one of Kazakhstan’s best. When the Soviet Union collapsed, almost all the Germans left for Germany, and the village fell into disrepair. The former residents of Peterfeld do not forget their homeland; they come from Germany to meet old friends and tidy up relatives’ graves.

“I left Kazakhstan almost 30 years ago,” the woman says. “I like Germany, but it has gotten worse lately: there are a lot of migrants from the Middle East, and they are very actively promoting LGBTQ+ issues. I don’t like living in such a country, and it will be even worse in the future. That’s why my husband and I want to get a second citizenship — Russian.”

Sketch Fourteen:

In Petropavel, a group of history buffs conduct tours of the old city for everyone. Often, young liberal guys and hipsters interested in their hometown’s history come on excursions. Sometimes, they gather after the excursion in some bar to joke, talk, and discuss various topics.

A middle-aged woman, one of the participants in the excursion, suddenly said, “These lands were never originally Kazakh; they used to belong to Russia.”

The woman almost exactly repeated the words of many Russian politicians who call the territory of northern Kazakhstan “a gift from Russia” and say that these lands “have always been Russian.”

Sketch Fifteen:

The train from the Kazakh Oral to the Kazakh Kostanay passes through the Russian Orenburg region. The railway section of this place belongs to Kazakhstan. Previously, the train made a long stop at the border: first, passengers were checked by Kazakh border guards, then by Russian ones. Now, you can travel through Russian territory without stopping. In Petropavel, the situation is different: the city station and the railway sections belong to Russia. A large map depicting Russian railways, including northern Kazakhstan territory, is inside the station building. Although the state border dividing Kazakhstan and Russia is indicated there, the map is drawn so that, at first glance, it seems that it is still one big country.

Sketch Sixteen:

At Sorochyntsi Fair, a local Ukrainian restaurant sold national treats: sandwiches with lard, dumplings, vodka. A little aside lay a tray on which all this was cut. When the treats ended, the tray was removed from the counter, and we saw that a map of Ukraine was drawn on it: a full-fledged color divided into areas. Even pieces of fat and dill adhering to the map did not spoil its appearance; on the contrary, they added artistic flair. Surprisingly, Crimea was also on the tray, but for some reason, all white, which is how usually, on political maps, neutral territories that do not belong to anyone are marked. Seeing that the tray attracted the attention of photographers, the restaurant employee quickly took it away.

Thomas Dworzak’s “Like a Blood Stain on a Handkerchief” is on view at the Egir Art Space in Almaty, Kazakhstan as part of the Beyond the Silence project. Read more here.