The Lebanese Civil War, 50 Years Later

50 years ago, Magnum photographers documented the Lebanese Civil War, a devastating conflict that shook the country for 15 years

Fifty years have passed since the start of the Lebanese Civil War on April 13, 1975. The 15 years of armed conflict, which killed approximately 150,000 people and displaced at least 800,000, continues to reverberate in Lebanon’s collective consciousness. The aftermath of the war changed the country’s trajectory; it brought about the Syrian occupation until 2005, and the Israeli occupation of southern Lebanon until 2000. The Israeli ground invasions in 1978 and 1982 eventually resulted in the removal of the PLO militia from Lebanon, and spurred the emergence of Shiʿi groups such as Hezbollah.

Driven by sectarian violence, class struggles, foreign interference and invasions, the war’s consequences still linger as the country grapples with internal crises, political instability and, more recently, Israeli bombardments.

In 1965, at the age of 23, Raymond Depardon traveled to Beirut for the first time, portraying the Mediterranean port as an idyllic oasis — a center for cultural and intellectual life in the Middle East. When he returned in 1978, the Beirut he knew had turned into a war zone; the city was in ruins, and continued to crumble before his eyes. His book, Beyrouth Centre-Ville (2010), juxtaposes these two visits, recording the before and after of the devastating conflict.

In the 1980s, Abbas visited Beirut, where the Green Line acted as a demarcation during the Civil War, separating the Christian majority in East Beirut from the Muslim majority in West Beirut. This stretch became an epicenter for the clashing militia, and because of the lack of traffic, lush vegetation overtook the strip, giving it its name. While the Green Line no longer exists, it remains a turbulent site in the collective memory.

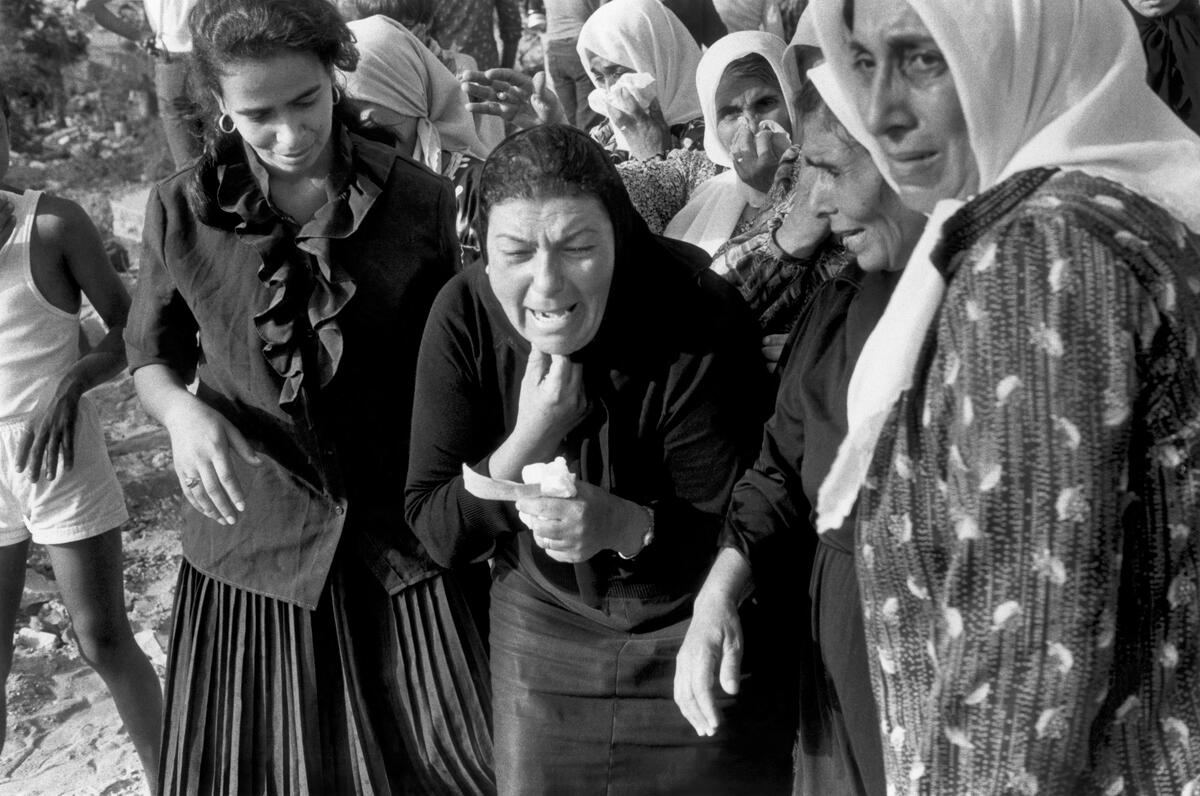

Chris Steele-Perkins photographed Lebanon extensively during the civil war, notably the 1982 Sabra and Shatila massacre, where the Israeli-backed Phalange militia killed thousands of Palestinian and Lebanese civilians. His photos also attest to the disquieting dissonances of war — children playing in the wreckage, a boy licking a lollipop as he passes a propagandist poster, and a man holding a machine gun in a thicket of yellow wildflowers.

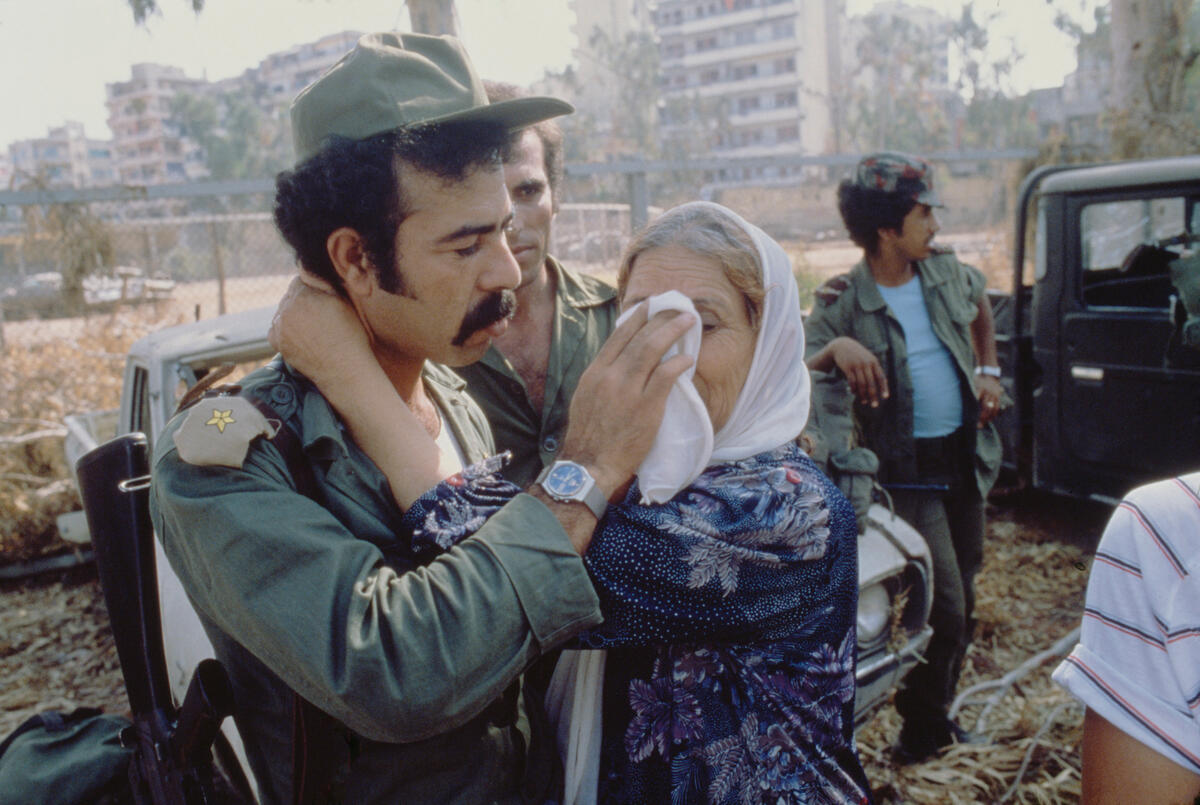

In 1982, Gilles Peress documented the Palestine Liberation Organization’s (PLO) withdrawal from Lebanon after being trapped by Israeli forces for 70 days, following a cease-fire brokered by the U.S., amid escalating tensions and Yasser Arafat’s growing influence.

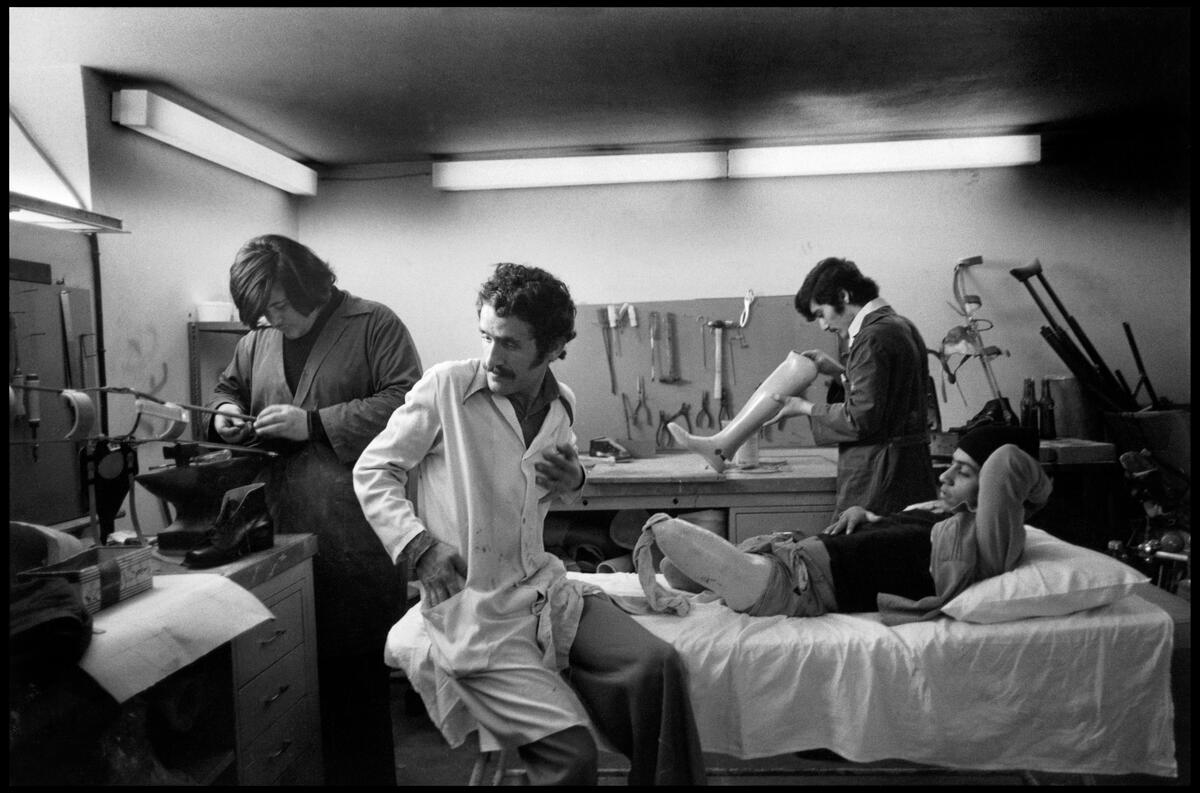

Eli Reed planned to work in Beirut for no more than three weeks. He ended up staying for over four months, chronicling everyday life during the civil war, which culminated in his book Beirut: City of Regrets.

Reed writes about his impressions while there: “My Lebanon experience began in 1982 during my Nieman Fellowship year at Harvard University. I had heard accounts of the 1982 Israeli invasion from journalists visiting the school. The stories compelled me to try to understand how the average Lebanese citizen could survive their days and nights. So I resolved to go and see for myself. I arrived in late September 1983, relatively wide-eyed with little historical background or perspective. […] I had little down time while I was there, photographing everything and anyone who came near. […] Lebanon holds the history of five thousand years or more of living. We point in silence at the fickle finger of ethical behavior — as if we had the right. What we should do is truly learn from it.”

After the war ended in 1991, Magnum photographers returned to the region to document the devastation in Beirut and the toll of the 15-year conflict on both the city’s infrastructure and its residents. Their images are testimonies of the relentless violence experienced by the country’s diverse communities, and facilitate our understanding of Lebanon’s past and present.

Myriam Boulos, who joined Magnum as a Nominee in 2021, was born in Lebanon in the direct aftermath of the Civil War. Her debut photo book, What’s Ours (Aperture, 2023), documents her home country, zeroing in on moments during the October 2019 uprising, when hundreds of thousands gathered across Lebanon to protest the widespread corruption of sectarian leaders and extreme austerity measures that crippled the population. Boulos also photographed Beirut after the disastrous port explosion in August 2020. Weaving intimate journal entries and fragments of conversation about the protests alongside her images, she explores sites of violence on nature and the body. “I just want to remove all this year’s data from my body,” she writes, “and start feeling subtle things again. Delicacy and magic.”

View a larger selection of work by Magnum photographers documenting the Lebanese Civil War here.

To license images from the Magnum archive, contact licensing@magnumphotos.com.