The Search for the Oldest Living Tree

A meditation on survival by Alec Soth

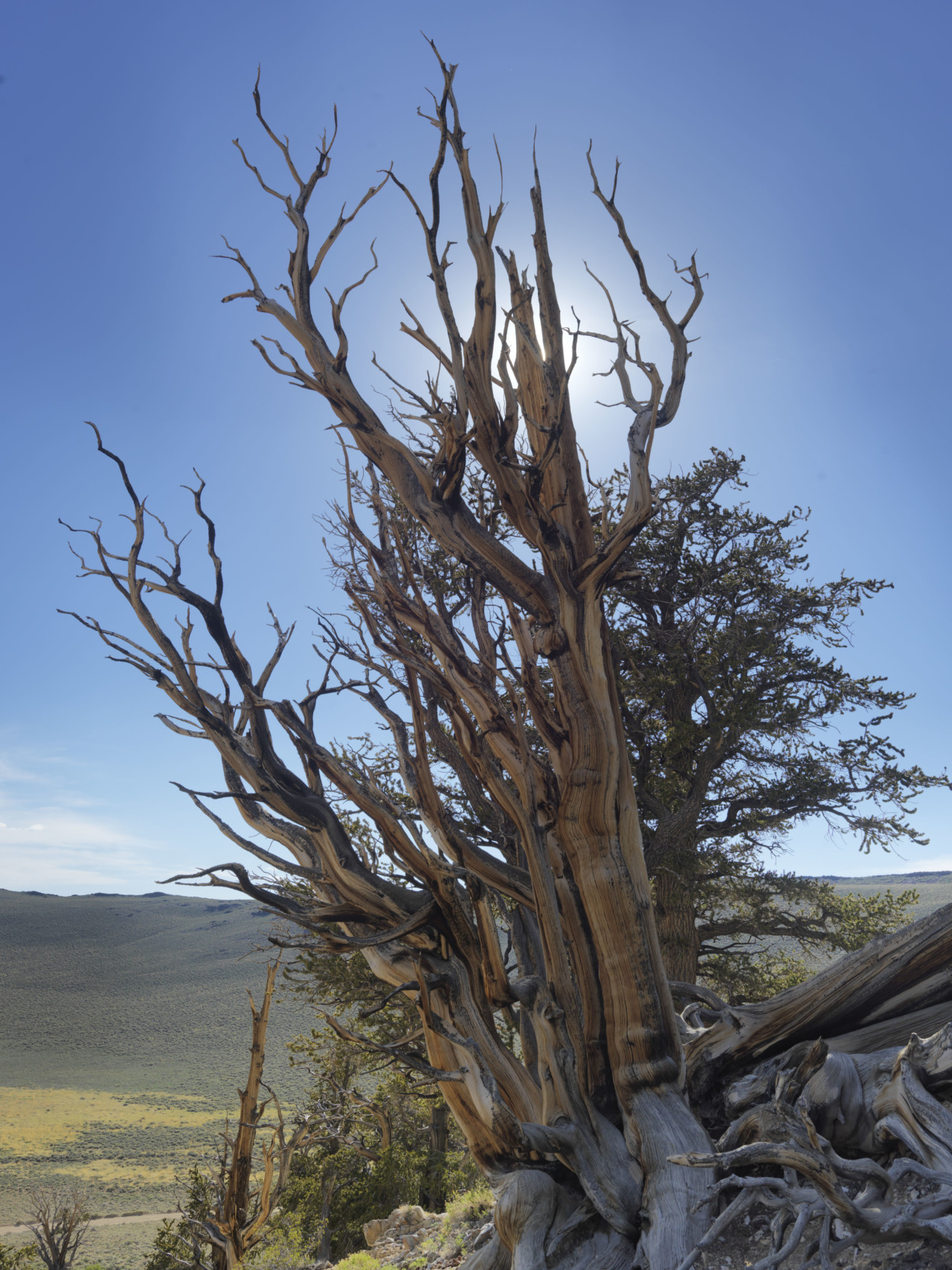

I was asked to photograph the oldest living tree in the world – a nameless legend whose location has never been revealed. But the best I could get from my sources was the location of the Methuselah, the second oldest tree. So I flew from Minneapolis to Las Vegas and then drove four hours north to the Ancient Bristlecone Pine Forest in the White Mountains of California.

I followed the instructions I’d been given but I couldn’t find Methuselah. In the thin mountain air I frantically inspected every tree in proximity but eventually gave up.

Close to the location, however, I found one tree that at least partly fit the description. It was one of the least impressive and almost falling apart. Was part of the reason why they kept its location a secret the fact it was so unimpressive?

"One of the reasons Bristlecone Pines have survived for so long is that they grow so slowly; it was a kind of gnarly, squatty, unimpressive beast."

- Alec Soth

This isn’t to say that any of the trees were that spectacular. One of the reasons Bristlecone Pines have survived for so long, I learned, is that they grow so slowly; it was a kind of gnarly, squatty, unimpressive beast.

Dejected, I started thinking about the banality of aging: the impressiveness of the achievement betrayed by the un-impressiveness of the exterior. With this in mind, I arrived at the nearest town, Bishop, and decided to go to the old folks’ home. I asked the woman at the front desk if I could meet their oldest resident, and she took me to meet Lloyd.

For over an hour Lloyd told me stories (selling watermelons in Alaska, catching a 500lb fish with ham in the South Pacific). I asked him what it was like to live alone in a nursing home. “It’s the shits,” he said, “I might as well paint bars on the windows of this son-of-a-bitchin’ place.”

I asked Lloyd if I could take him out for the day to look at the ancient bristlecone pines. “Sure, I’ll take my cane,” he answered, “I’ll make it, I guess.”

But when we got to the park, Lloyd only managed to make it about ten yards from the car. He sat on a bench while I hopelessly looked for Methuselah.

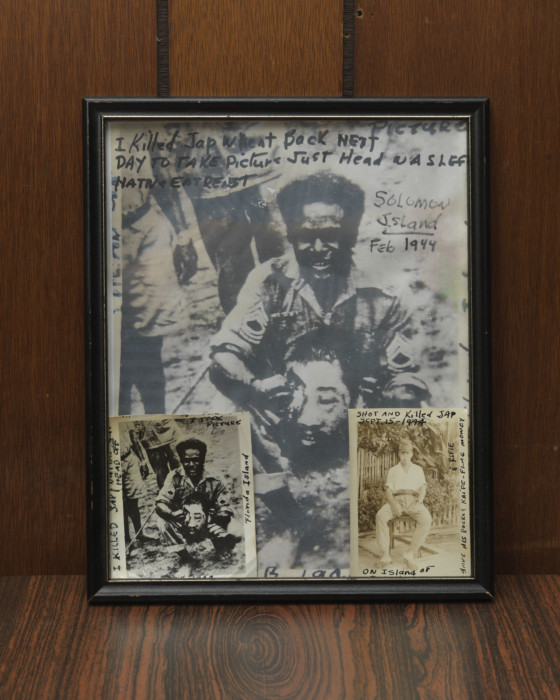

On the drive back down into town Lloyd wanted to show me something at the local VFW (Veterans of Foreign Wars), where some of his old war artefacts were stored. He told me he’d shot a Japanese soldier in the eye. When he went back to the area where he’d killed this man the next day, there were locals who had cut off his head. Lloyd claims they were going to cook his body. He showed me a photograph of one of these locals holding the man’s head.

If that wasn’t gruesome enough, he also had a photograph of the man when he was alive and the knife they used to cut his head off with.

Lloyd said he didn’t value life, never really did. He would be happy if he died right now. In fact, he says he wouldn’t have minded that much if he had died as a young man.

Lloyd and I went out to dinner. I asked him about his wife, who died 18 years ago. He had been married 51 years. “51 years and 4 days,” he said. I asked him if he had ever had an affair, he hadn’t. Then, he paused and said, “But… she did.”

Ten years after his wife died, he opened a padlocked cedar box. Inside, he found hundreds of love letters and naked pictures of her and her lover. This discovery crushed him. So he burned it all and said if she wasn’t dead he probably would have killed her himself.

The next day I went out to view the ancient Bristlecones once more. But instead of looking for Methusalah, I simply admired the variety of these 5000-year-old gargoyles.

“Life… it just goes on,” Lloyd had told me. And as the sun dipped below the Sierras, I thought about the trees enduring yet another night on the mountain.