The End of the Beginning: Closing Standing Rock

Larry Towell bears witness to the emotional acceptance and final throes of resistance as the protests against the North Dakota Access Pipeline are finally cleared

After months of protest and public outcry, on December 4th, the US government announced it would halt construction of the North Dakota Access Pipeline due to environmental concerns. Two months later, under orders from recently-inaugurated President Trump, the Army Corps of Engineers announced they would close down protest camps – which are known as prayer camps amongst the native communities – near Lake Oahe on Wednesday, February 22nd.

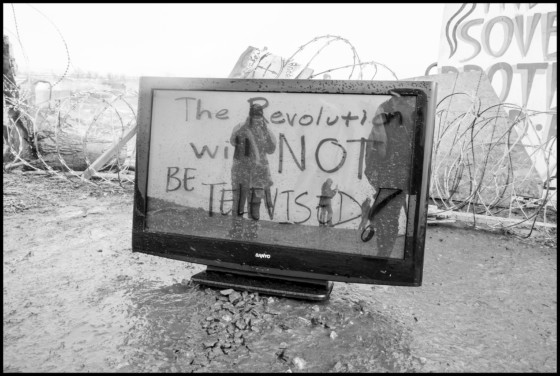

On February 21st Larry Towell, who has spent years documenting Native American issues in Canada and the US, made his third trip to the Dakota Access Pipeline protest camps at Standing Rock. The following day, the deadline to evacuate the Oceti Sakowin camp, most of the remaining demonstrators bid tearful farewells to their fellow activists known as Water Protectors. Some decided to remain and later that afternoon authorities raided the camp entrance area to round up and arrest journalists, who’d been previously ordered to leave.

"It was emotional, most people had left, most sites were empty - it was a ghost village"

- Larry Towell

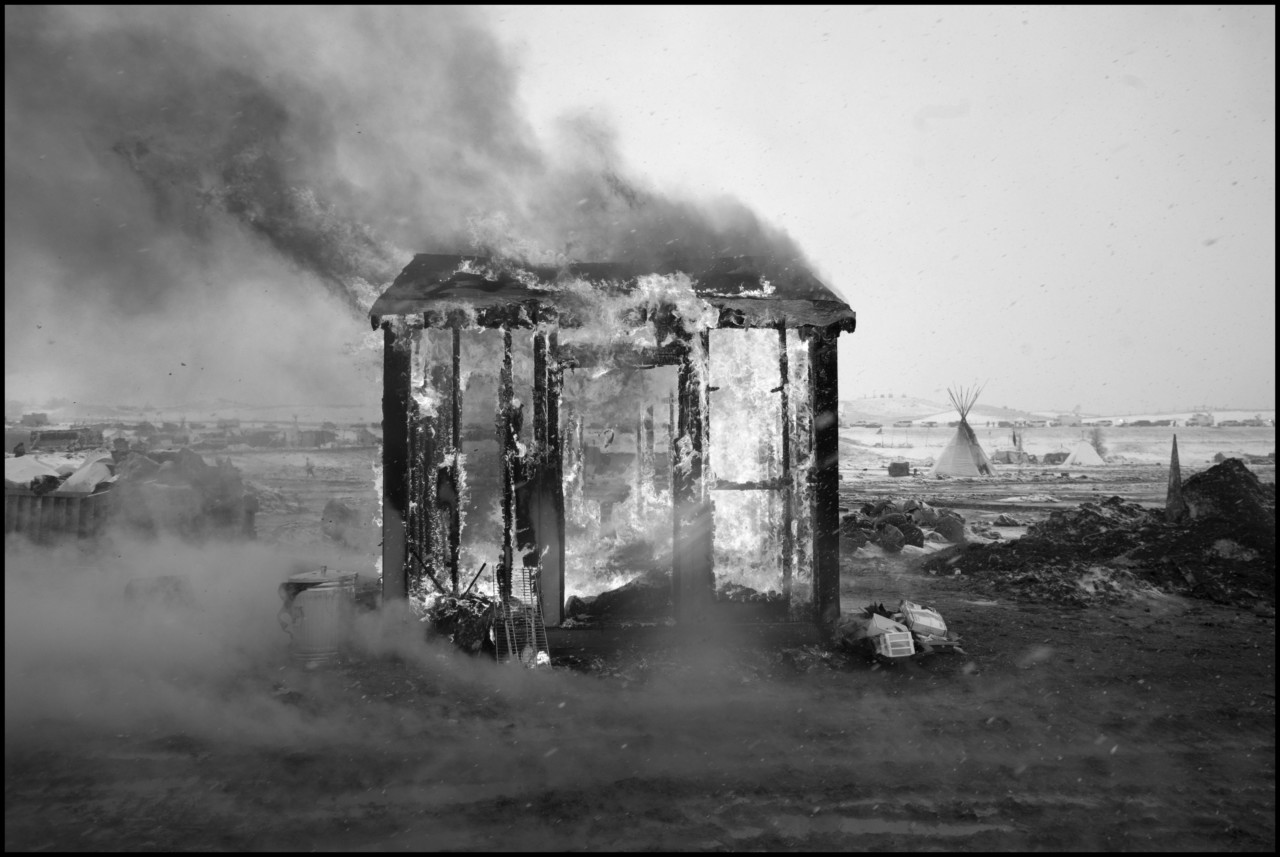

“I arrived late on the 21st and spent the 22nd documenting the voluntary emptying of the camp. This is when I took the photos near the sacred fire” says Towell. He describes the atmosphere: “It was emotional, most people had left, most sites were empty – it was a ghost village. It was snowing heavily at times. It was also very thick with smoke. The earth was heavy and deep mud was making it hard to walk – and it was very cold. There were acres of debris; it was very ominous. Also, at any moment the police could come in, but they remained back on the highway.”

"The elder said that because of the previous behavior by law enforcement disposing of tipis and ceremonial items in a disrespectful way in October, the structures should be burned in a ceremony to protect them from disrespect"

- Larry Towell

With a sense of acceptance, most people remaining left on the 22nd. “Those people cried, prayed, and said goodbye. As they left, some set fire to their homes. A Dine (Navajo) water protector asked his elders back home what they should do about the traditional structures that they built in camp. The elder said that because of the previous behavior by law enforcement disposing of tipis and ceremonial items in a disrespectful way in October, the structures should be burned in a ceremony to protect them from disrespect.”

The next day, armored vehicles entered the camp, forcing the holdouts to flee onto the frozen Cannonball River. The main and the biggest camp, Oceti Sakowin, which was once inhabited by as many as 5,000 people (some have said 10,000) was entered by state and national police driving Humvees, dressed in riot gear, and carrying assault rifles. The remaining few protesters ran onto the ice of the Cannonball River to escape. “Luckily, the ice held, which is a miracle because it was beginning to melt,” said Towell. Having made it to the other side, they continued their protest by singing and praying for four or five hours until the BIA (Bureau of Indian Affairs) police, which Towell describes as taking a “kinder” approach, entered on the native-owned south bank of the river and they finally disbanded.

Although this marked the end of the protest camps opposing the DALP, it is not, according to Towell, the end of activism by the native people. “The Sioux tribe and their supporters in the camp learned an awful lot over the months about organization, communication, fund raising, the media, the government, the oil companies, which will spawn a national movement modeled after Standing Rock,” he explains. “It will also, I believe, someday force the US government to re-visit the treaties. These issues have been boiling out here in Indian country for two centuries. The environmentalists have joined, giving the movement its popularity. It will grow as pipelines continue to spread across the continent, and particularly those that cross native land.”