Working in Photobook Publishing: Lesley Martin

Aperture’s Creative Director talks to Magnum about lessons learned during an illustrious career working on photography books

New York City-based Lesley Martin is creative director at Aperture Foundation, and publisher of The PhotoBook Review. She has edited numerous photobooks, including Takashi Homma’s Tokyo (2008), Rinko Kawauchi’s Illuminance (2011), LaToya Ruby Frazier’s The Notion of Family (2013), and recent books by Richard Misrach and Gregory Crewdson. In addition to her work on The Chinese Photobook, she was a contributing editor to Japanese Photobooks of the 1960s and ’70s, The Latin American Photobook and in 2012, cofounded the Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards. She has curated exhibitions that have traveled both nationally and internationally and her writing on photography has been published by Aperture, FOAM, Ojo de Pez, and Lay Flat among other publications. She currently teaches a graduate course on the photobook at the Yale University School of Art.

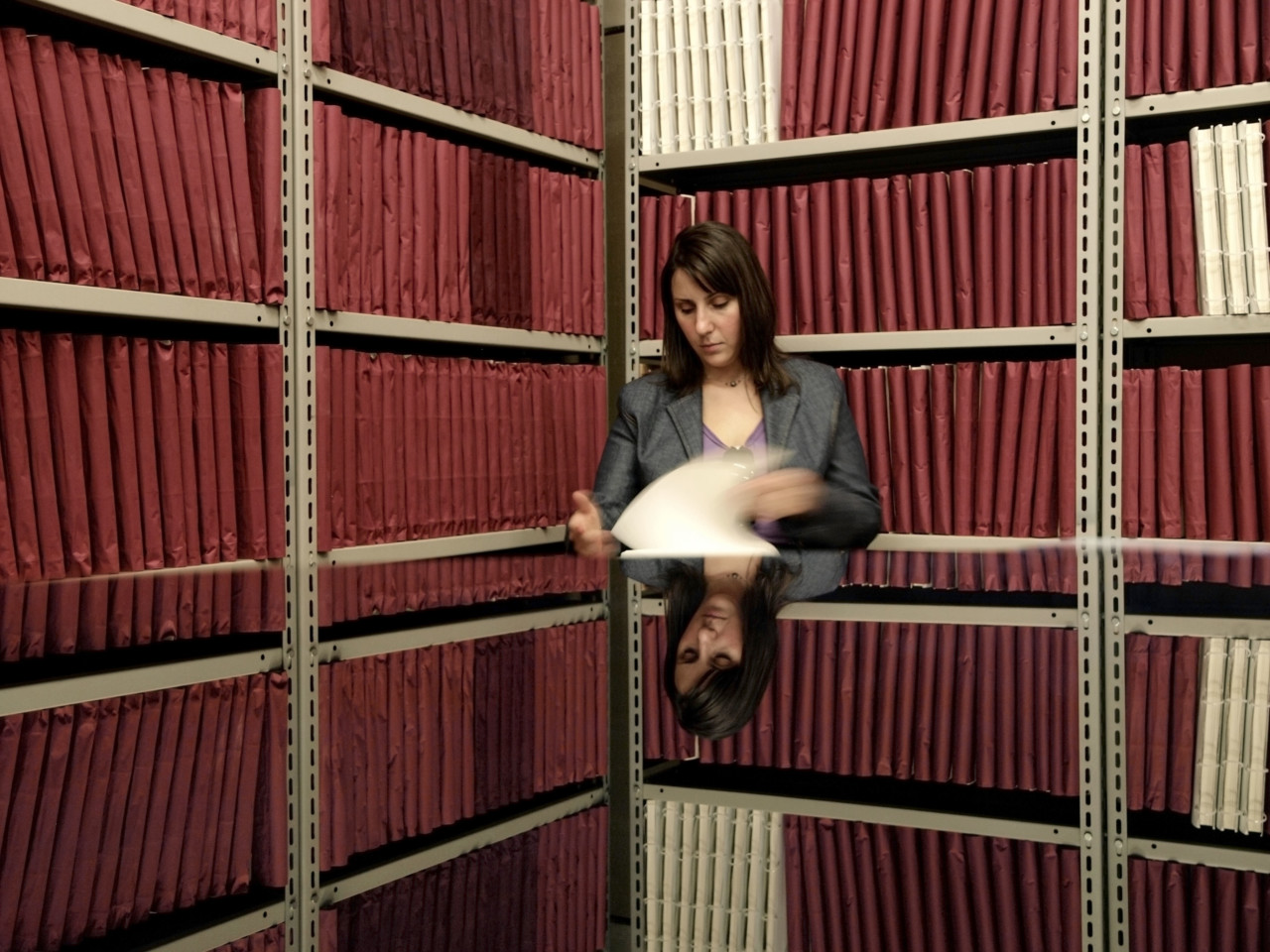

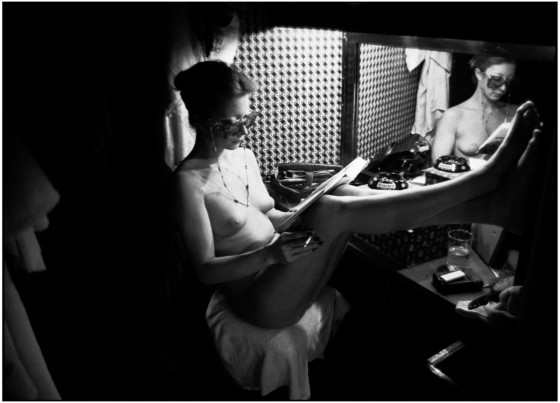

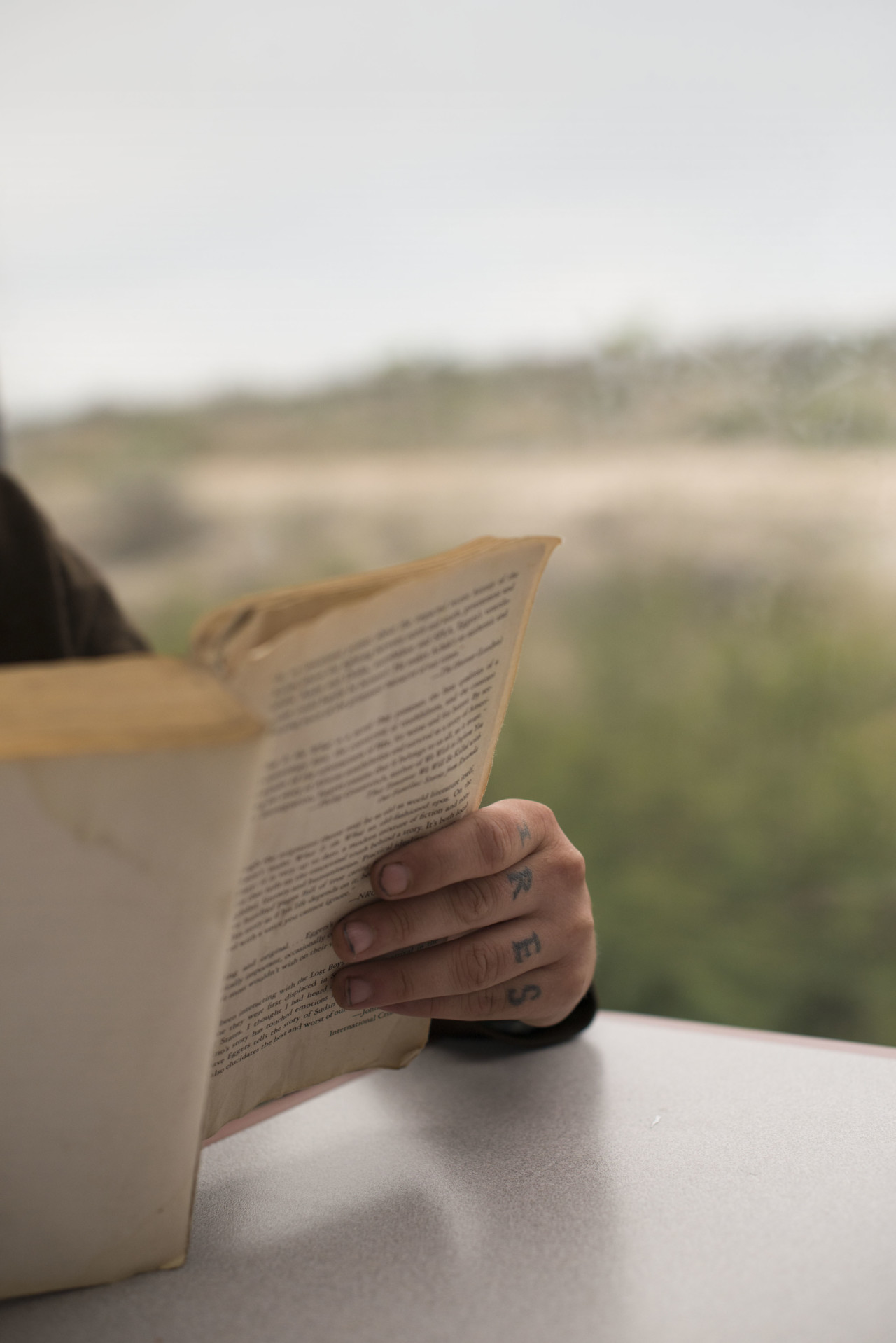

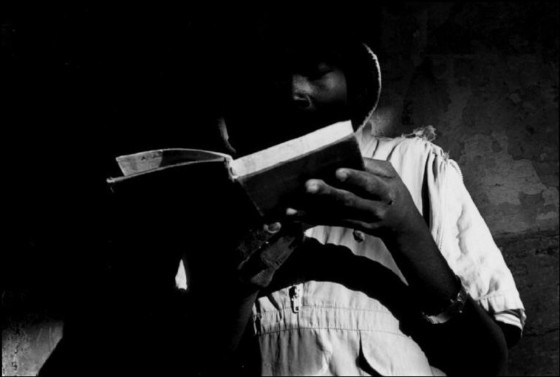

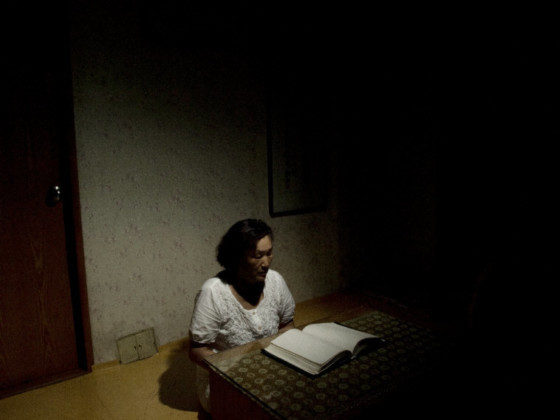

With her professional photobook publishing background, Martin is a judge for the 2017 LensCulture and Magnum Photography Awards. Here, she talks to Magnum about an illustrious career, offering advice for photographers interested in publishing photobooks of their own. Martin delved into the Magnum archives and curated her favourite images, presented here alongside her interview. She says, “An archive can be a forest; a thicket of images that’s difficult to parse. All you need is a single thread – an idea or a word or two to navigate by and suddenly a path appears.”

How did you begin working in photography? What are your main career milestones or turning points that led you to the position you are now in?

Although I’d been interested in and engaged with photography in different ways, an internship at Aperture was my entrée to the ‘real’ photo community. That said, I don’t think I’d be where I am now if I hadn’t taken time after my internship to explore other options, to freelance, and to work with other publishers before coming back to work at Aperture. I can’t point to one particular milestone or another but I’ve had the good fortune to work closely with many amazing photographers, designers, writers and other editors and to learn something from each of those experiences.

"The photobook community cannot be made-up exclusively of book makers – someone has to buy them, too. It’s a karmic thing."

- Lesley Martin

Photobooks allow a photographer’s work to play out over many pages, as it builds a narrative, but much of the photography that people see every day is seen in much smaller edits, or even just single images, on social media. What does the photobook do that is unique and cannot be conveyed through other media (e.g. digital media, magazines, or gallery exhibitions)?

It’s important to think about how a book functions differently from the wall or the screen. There’s the obvious physicality of the printed page as something that takes into account the physical presence of a reader, with the book in front of them, held in their hands. There’s also the way that a book functions as a binding agent for text and series of images; these otherwise disparate elements come together in a concrete, permanent way. A book is able to focus, contain, and contextualize a body of work with different types of text, additional information, and other elements that help give further depth and texture to a project. It’s a less ephemeral, more directed method of connecting a photographer’s work to an audience.

Martin Parr thinks we are currently in the golden age of the photobook. Do you agree? How has the photographic industry – and the photobook publishing industry – changed over the past decade?

This is a question that has been answered and debated in so many different ways. The most obvious response is Dickensian: it is the best of times and it is the worst of times. The best because there’s so much attention being paid to the possibilities of the book; the bar is high for anyone publishing today and there’s a lot of energy and creativity coming out of the indie and self-published book makers. Additionally, there are so many opportunities for a photographer to tap into international communities – online conversations, umpteen different photobook fairs, etc. It’s also the worst of times because we are awash with photobooks and it can become overwhelming; difficult to know where to focus sometimes. And with so many more books being made overall, it’s inevitable that there are also increasing numbers of poorly conceived and executed books.

"Look carefully and try to figure out how the books you like were put together"

- Lesley Martin

What is the most memorable book project you have worked on and why?

It’s really hard to choose one – I’ve worked on over a hundred books in the past twenty years. But certainly one that stands out as highly unusual and really fun was Daido Moriyama’s Printing Show, which I brought to New York, in collaboration with Ivan Vartanian, Akio Nagasawa, and the rest of Moriyama’s team. This was a two-day performative, make-your-own-book event that took inspiration from Moriyama’s prior interactive book-making project and resulting publication, Another Country, New York, and has now been repeated in various ways and various venues around the world. Anyone who came to the event essentially committed to becoming an editor for their own book, choosing from a variety of available images that Moriyama had preselected. People came and stayed for hours, puzzling over which images to choose and what order to put them in.

What advice do you give to aspiring photobook makers?

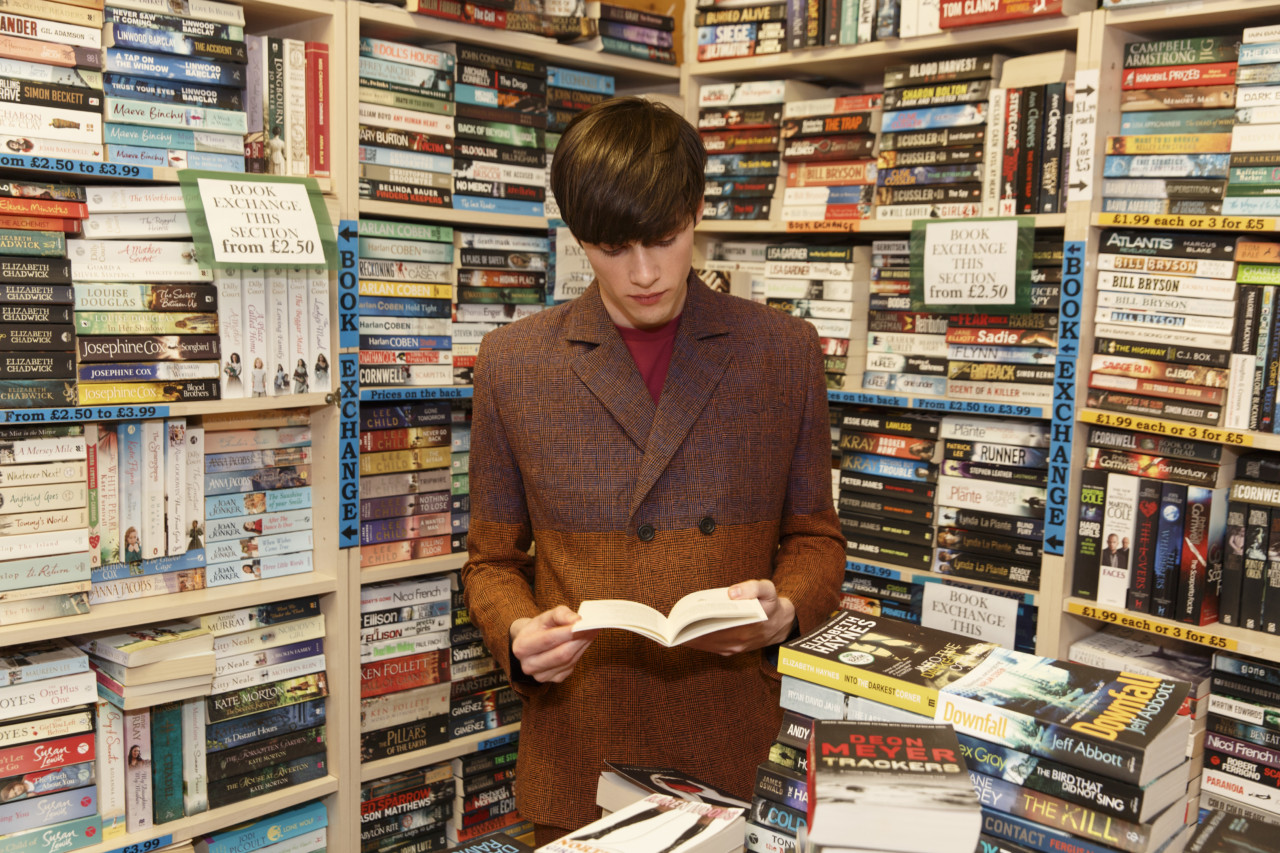

Three things. First: Take the time to really assess why you want to make a book – this sounds obvious, but a lot of people come to me with the impression that they should make a book, but without having really thought it through: what is the concept behind your project and book – what is it really about? Who is your audience? If you can’t answer those questions honestly, you’re not ready to publish a book. Note that this doesn’t mean you can’t make your own book. Go ahead and make a dummy, make a small private edition and try out the form. But publishing a book is a slightly different step from making a book, practically speaking. Second: take the time to identify what you like in a book. What are you drawn to in a bookstore and why? Look carefully and try to figure out how the books you like were put together – what decisions were made in choosing the materials, in designing the book? Third: buy some books. The photobook community cannot be made-up exclusively of book makers – someone has to buy them, too. It’s a karmic thing.

When judging awards, what are you looking to catch your eye?

There are so many photographers out there that can produce a strong, solid body of work. What’s much more difficult is producing something that is energized and propelled by a clear and unique point of view.

How can you tell when a good photographer has the potential to be really great?

It’s impossible to try and predict who’s going to be ‘really great’ – not the least of which is that there are many definitions of what ‘really great’ means – a really great teacher? A really great gallery artist? Someone who has the most magazine covers under their belt? I’m looking for work that is thoughtful and that manages to push at the boundaries of my understanding of a particular subject; at the boundaries of the medium itself. There’s no simple formula – but the ability to surprise me and to compel me to come back to look again and to engage further with the work is a good starting point.

Lesley Martin is on the panel for the Magnum New York Photobook Masterclass. June 17-18. More information, and applications here.