Tunisia’s Youth Champion

Newsha Tavakolian follows Asma Kaouech, a young lawyer-activist fighting for freedom of expression in Tunisia

In Tunisia, change came suddenly — after the death of a vegetable seller in January 2011, protests swelled—toppling the 23-year dictatorship of President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali. It sparked a series of protests in the region, advancing to Egypt and Libya. But nearly seven years on, Tunisia remains the Arab Spring’s lone success story, a fledgling democracy with a constitution since 2014 that guarantees freedom of expression—though the military and police haven’t always respected these laws. More recently, the country has struggled as terrorist attacks have knocked back the tourist economy, with hundreds of young people joining militant groups in Libya, Iraq and Syria. But civil society remains active, with the Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet — a democracy group — being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2015 for its “decisive contribution” to building a pluralistic democracy after the revolution.

To mark 30 years of the Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought — an annual prize established by the European Parliament to pay tribute to human rights work — Magnum photographers have worked with the European Parliament for a book of writings on human rights and the people fighting for them today, as well as an exhibition launching this month. Newsha Tavakolian trailed Tunisian lawyer-activist Asma Kaouech, who has fought for gender equality, young people’s right to participate in politics, and freedom of conscience. This is her story.

Asma Kaouech is a 25-year-old lawyer. Her father was a philosophy teacher who gave her some good advice: not to watch Ben Ali’s television; instead, to read books — those of Kant or Heidegger — and to study democracy, individual liberties and women’s rights. “He brought me a lot of books on feminism,” says the young Tunisian, who was brought up in the capital, Tunis, but originally came from the south.

“Throughout my childhood, he taught me to be a person with values.” Someone who nurtures values as one nurtures hope. These words characterize this activist, whose baptism of fire took place in 2011, two weeks before the revolution that led to the fall and departure of the dictator Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali.

Tunisia certainly has thousands of activists like Asma to rely on around the country—and they represent a considerable human asset. But as highlighted by the Iranian photographer Newsha Tavakolian who followed her, this Asma is unique—through her words, her actions and her way of transforming idle street children who are at risk of going down the wrong path into white-faced clowns.

First, there was the pain of a man, Mohamed Bouazizi, the street vendor who set himself on fire in the small town of Sidi Bouzid on January 4, 2011 and sparked an unprecedented wave of protests. An entire people, exhausted by the police-state regime of Ben Ali and his clan, found their voice. But people, once liberated, do not always know what to do with their newfound freedom. So a time came when power was handed to the Islamists of the Ennahda party, which meant another source of pain. But history was moving on, driven by the street movement, which was calling for a new constituent assembly and a new constitution, which was finally adopted on January 26, 2014. Asma is happy: “That legislative document guarantees many new rights: gender equality; young people’s right to participate in politics; and freedom of conscience. It is a major step forward.”

Her protests were not in vain. It was not for nothing that she spent two days in prison before the revolution, when Ben Ali’s police put her behind bars. She emerged from there after having promised the impossible: that she would no longer express her political opinions. She pledged in writing to no longer demonstrate or to study — yes, even just to study — but instead to go home and keep quiet. “Thank God the revolution came,” says Asma. “One of the greatest moments of my life! So many things moved me, like the people who organized themselves to protect their neighborhood. They went on patrols. The women prepared meals. We all met up to share our stories, our misfortunes and our aspirations.”

"An entire people, exhausted by the police-state regime of Ben Ali and his clan, found their voice."

- Asma Kaouech

Civil society activists clashed with the Islamists who wanted to impose religion within the state. Asma was the only student who succeeded in becoming a trainee in the new assembly. She wanted to see what the members would decide. They told her: “Go to the beach!” She stayed where she was. They did not know how stubborn Asma could be. It was at that time that Asma and a handful of activists created Fanni Raghman Anni (FRA), which literally means “an artist in spite of myself.” A revolution within the revolution. Voices and bodies that move, express themselves and struggle.

“During the sit-ins and demonstrations, people started to use street theater, art and culture as a new tactic to defend human rights and to attract people’s attention.” When the FRA first emerged in 2011, it was just a movement, but two years later, after developing its anarchic practices in cafés, it became an association. “Our main task was to combat marginalization in the heart of the country, in neighborhoods and among the poorest,” explains the lawyer. She has vast experience in oratorical art, mime and performances that make a deep impression and that can become a form of street fighting — a peaceful struggle with the aim for everyone to be able to see themselves reflected in other people and in their weaknesses, hopes, anger and confusion.

Three actions were then carried out at the same time: workshops all over Tunisia, lasting around 10 days, bringing together some 30 young people who were expected to ‘perform’ on the theme of human rights; artistic performances on the same subject, organized with professional actors; and finally, in Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey, activities in refugee camps to offer social, cultural and humanitarian support to marginalized people. Having gained this experience on the ground, Asma quite naturally came to direct her action towards the prevention of radicalization.

“Tunisia is the biggest exporter of young jihadis,” Asma says. “Our project is called ‘We are here.’ Human rights are linked to peace; it must therefore be preserved by means of this work done in advance. We have an office in the center of Tunis, where I work virtually full-time. There are five of us between the ages of 20 and 29 who are employed there. We receive funding from the United Nations and the European Union.”

Preventing radicalization. These words resonate strongly from Asma. “Our office was set on fire in 2014, on the anniversary of the revolution. I felt that I was in danger. “Performers” have also been physically attacked by Salafists while on stage. The artists were sent to prison, not the Salafists. They remained free.”

The subject is a sensitive one. In recent years Tunisia has experienced attacks unprecedented in its history, as for example on June 26 2015 when a terrorist disguised as a holidaymaker, his Kalashnikov hidden in a parasol, killed 38 people in cold blood and injured as many near Sousse. On March 18 of the same year, at the Bardo Museum in Tunis, 21 tourists were killed by gunmen. And on November 24, 2015 a terrorist attack targeted a bus belonging to the presidential guard. These three attacks were claimed by ISIS before a fourth similarly deadly attack was carried out against Tunisian security forces on March 7 2016 in Ben Guerdane near the border with Libya, in which 50 people were killed, including around 30 jihadis.

Asma and her friends know the details of these tragedies. Through their attempts to help young unemployed people tempted by crime or on the verge of radicalization, they seek to overcome these deadly impulses, which point to the young people’s desperation.

Tavakolian’s lens has managed to capture wonderfully well both the positive and the negative aspects of this vital undertaking. On the positive side there are young people that Asma took to visit the Bardo Museum to show them—through mosaic art—what a great history they had and what a source of pride it should be. Without her and her commitment, these young people would never have had the idea of visiting such an enlightening institution, treating it as if it were alien or taboo to them. Another positive aspect is the energy displayed by painted faces and bodies engaged in improvised theatre on a street corner or in a Tunis park, with the aim of sharing with a curious audience the story of their lives, their suffering, their anguish and the humiliations that have brought them to their knees.

"I realized that radicalization had nothing to do with Islam. These young people are angry because they feel excluded from prosperity."

- Newsha Tavakolian

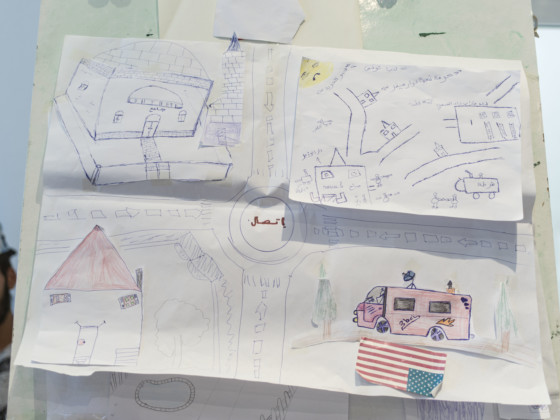

These humiliations inspire hatred in them, sometimes to such a point that they want to kill others or, like Mohamed Bouazizi, to kill themselves. Also positive are the drawings made by the same marginalized young people when Asma and her team asked them to imagine the house of their dreams. “I realized that radicalization had nothing to do with Islam,” stressed the photographer. “These young people are angry because they feel excluded from prosperity. Their frustrations are due to the lack of opportunities to escape, other than by selling drugs. Opportunities and material security elude them. They draw large houses in order to denounce the inequalities and injustices of which they consider themselves to be victims.”

The exercise is therapeutic. Some of them draw a house isolated from others, as if to underline more clearly that they are separate and will never genuinely become part of society. Once they have put down their felt-tips, the members of the association encourage discussion, give explanations, listen and provide reassurance. The young people can freely express themselves without feeling judged or rebuked. This is prevention by means of kindness and empathy, values that struck Tavakolian throughout her reporting with Asma.

The negative side is the faces of young people threatened by radicalization. In the case of both boys and girls, their expressions are signals of distress. They may sometimes look resigned, passive or else inquiring: Asma is familiar with all of this. It is with the aim of wiping these looks from their faces that, together with other young people, she fights for freedom of expression in Tunisia, so that those left behind can finally find reasons to live rather than die or kill themselves.

“I am very proud of young people in Tunisia,” she says, speaking as an upholder of the objectives of the revolution: ‘dignity, freedom, work.’ She does not abandon hope. Didn’t four Tunisian civil society organizations receive the Nobel Peace Prize in 2015 for their major role in the success of national dialogue? “We have become household names in the country,” Asma rejoices. Tunisia has a bright future ahead of it.

See the stories from this series here.