The Benevolent Voyeur

Darran Anderson muses on the significance and the symbolism of windows in Elliott Erwitt’s photography

The camera and the window are intrinsically linked. Both are portals to see through and frames in which to be seen. The essence of photography, at its simplest and most brilliant, is the capture of light. Windows exist to do something similar; to allow sunlight to pass into interiors, to capture it fleetingly in rooms. In the process, both the camera and the window reveal that which might otherwise be concealed.

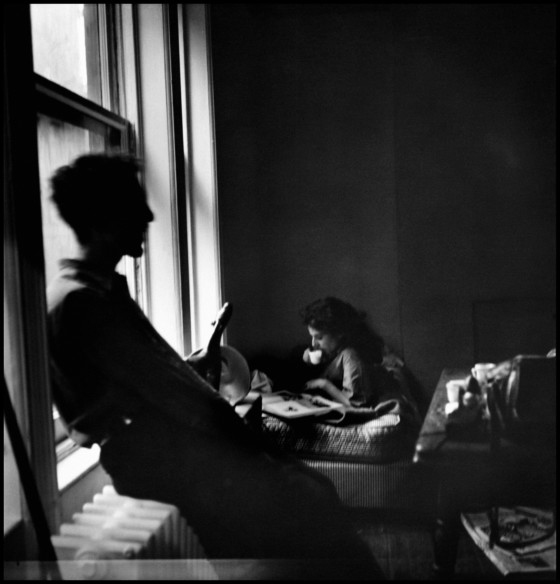

There is something of Vermeer to Elliott Erwitt’s shot of a New York room in 1949. Lit by a window to the left, it illuminates a scene that is both domestic and enigmatic. In the background, Mary Frank is preoccupied, nonchalantly reading and drinking. Robert Frank sits in the foreground. His features are shrouded yet he seems deep in thought. Though he is leaning back, he seems taut, poised, an impulse away from saying or doing something urgent. In a single image, there is ease and tension.

"In Erwitt’s work, we find the revelatory thrill of the benevolent voyeur; a position occupied not just by the photographer but also by the viewer and, very often, the subject"

- Darran Anderson

In Erwitt’s work, we find the revelatory thrill of the benevolent voyeur; a position occupied not just by the photographer but also by the viewer and, very often, the subject. His shots of windows are like visual poems on the themes of watching and being watched. The silent dialogue of passing glances we undertake every day is given permanence.

For Erwitt, there is no great elitist mystery to photography; the skill comes in curiosity, preparedness, practise and good fortune. “After following the crowd for a while,” he pointed out in ‘The Private Experience’ (Crowell, 1974), “I’d then go 180 degrees in the exact opposite direction. It always worked for me, but then again, I’m very lucky.”

Erwitt accompanies the crowd in a train station in Budapest, 1964, waving to their departing loved ones, emotional and oblivious to the camera. Then there is a turn, to capture both a departing lady, consciously or unconsciously avoiding his gaze, and his own self-portrait reflected in the train’s window. Then there is a moment when the scene changes, the train pulls away, and what was a single glance has already become both art and history on a roll of film inside a machine held in his hand.

The ability to find curious details in ordinary scenes (and relatable details in star-studded events) is a feature of Erwitt’s photography. The iconic nature of many of Erwitt’s photos might work against his spirit of looking closer. We might take his classic romantic photos at face value but they raise interesting questions when you ask yourself how they were taken. Were they surreptitious or even partly staged? The young girls that excitedly crowd at the window of Fidel Castro’s car in 1964 may resemble fans of pop stars from that same era but there is also a hint of unease when we consider the vulnerabilities of contemporaneous politicians in motorcades. By the time we reach 1986, we find Andy Warhol, having narrowly survived an earlier assassination attempt, cocooned away in a limo with the darkened bunker-like windows.

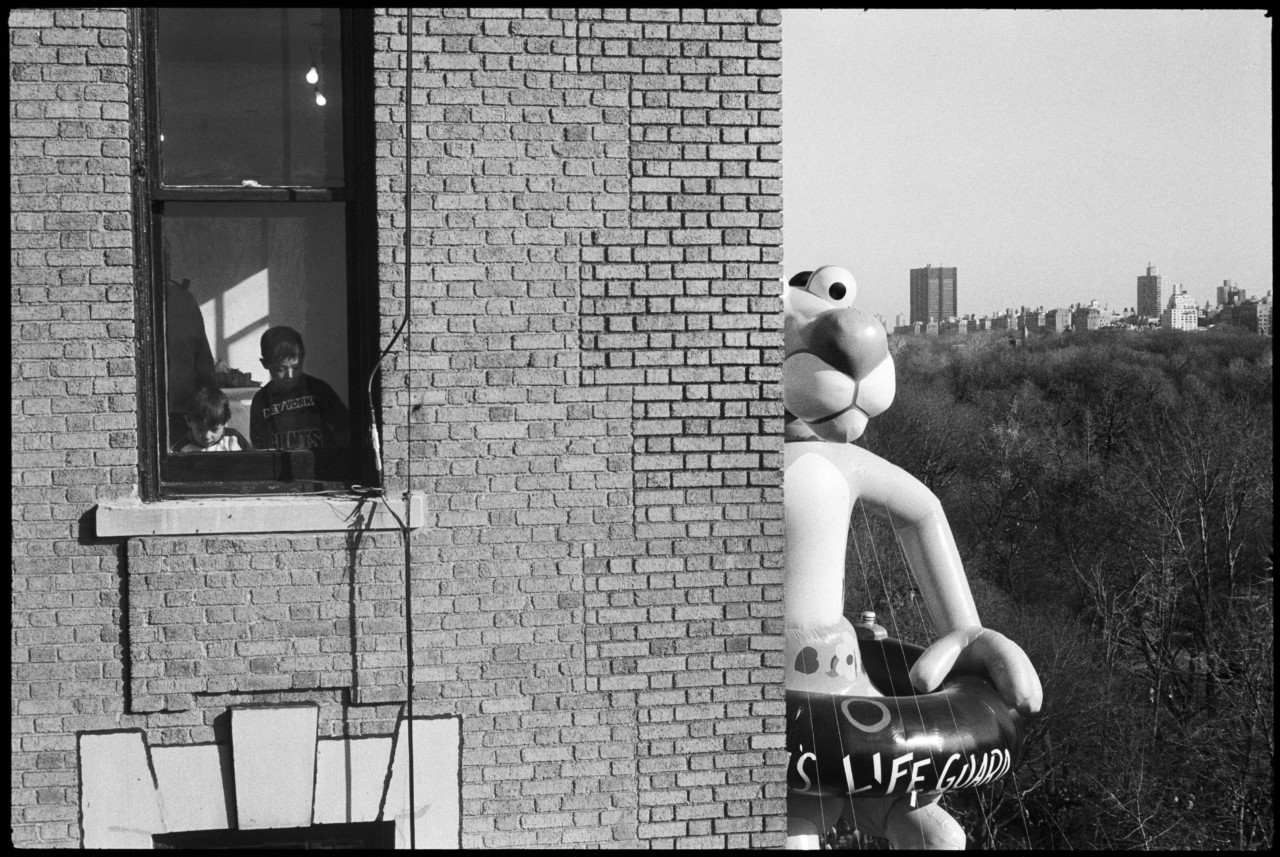

There may be a nightmarish menace to the sudden appearance of a face at the window but there can also be a dream-like quality. Erwitt’s photographs can be wondrously playful as exemplified in his shots of Macy’s Day Parade in 1988. These are all the more gleeful and surreal because we can see, in the form of gargantuan cartoon figures, what the children have not yet seen.

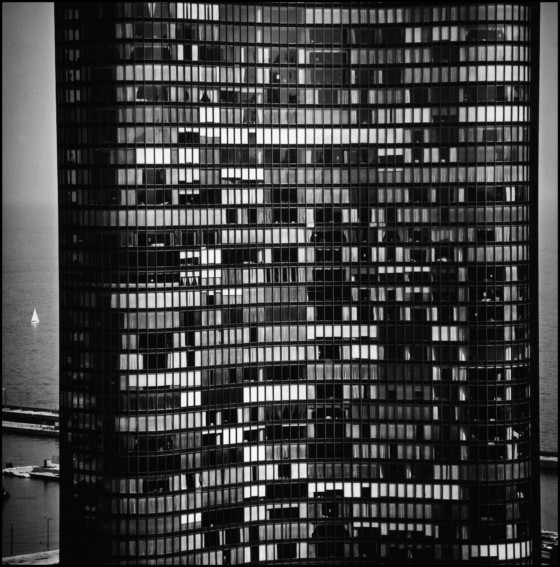

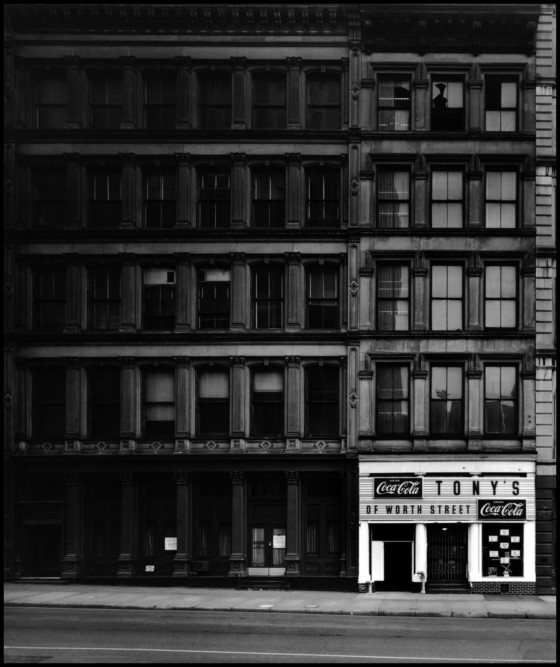

The parade passes and the city almost returns to normal. Except it was never quite normal to begin with. Buildings rise to heights and contain such complex detail that they seem both awe-inspiring and inhuman. Down on the empty streets, between these manmade ravines, the atmosphere can change from one of monotony to eeriness to the sublime. A photo might even contain all three of these states simultaneously. Passing citizens gaze into the windows with desire or disconcertment. In a Japanese market, a little girl and a fish stare fascinated at one another through the aquarium glass. Each gazing with curiosity, through a window, at a world that would prove fatal to them.

"The camera cannot show us the present while the window cannot show us the past"

- Darran Anderson

Photographs are windows to other places but also other times, to which they are bound. A boy in Colorado, 1955, looks through the cracked window of an automobile. It could be the result of nothing worse than loose chippings but the impact, hovering over his eye, has a sense of kinetic violence to it, like a bullet-ridden scene from a gangster film. Yet the photograph is still, and the boy is contemplative. There is more beauty here than horror.

Time is key to the difference between these gateways. The camera cannot show us the present while the window cannot show us the past. We have a passing glimpse of a pedestrian in Milan 1949 and we know that this is both an authentic replication of a moment and it is the image of someone likely long-dead. It is at once vital and haunting. Similarly, the dynamism of the photo of a boy looking back out of a train window in New York 1955, onto a track that disappears off towards a vanishing point, is both accurate and illusory. The photo seems to move but it is, of course, fixed. It is a stationary split-second rather than the journey and motion it implies.

We do not directly view the window in Erwitt’s 1953 photograph of a New York bedroom. The scene captured is only an instant. The cat will not remain motionless for long. The baby will not always remain a child. The adoring mother will not always be alive. Yet, for as long as that image survives, that moment in a room in New York City in 1953 will always be there, never truly lost, bathed in light passing through an unseen window into an unseen camera.

Darran Anderson is the author of ‘Imaginary Cities’ (Influx Press/University of Chicago Press) and the forthcoming ‘Tidewrack’ (Vintage/FSG). He is currently writing ‘Rooms’. He lives in London.