The Photographer in the Frame

Ahead of World Selfie Day 2018, the many variations of Magnum photographers' self-referential images and self-portraits are put into perspective

Magnum Photographers

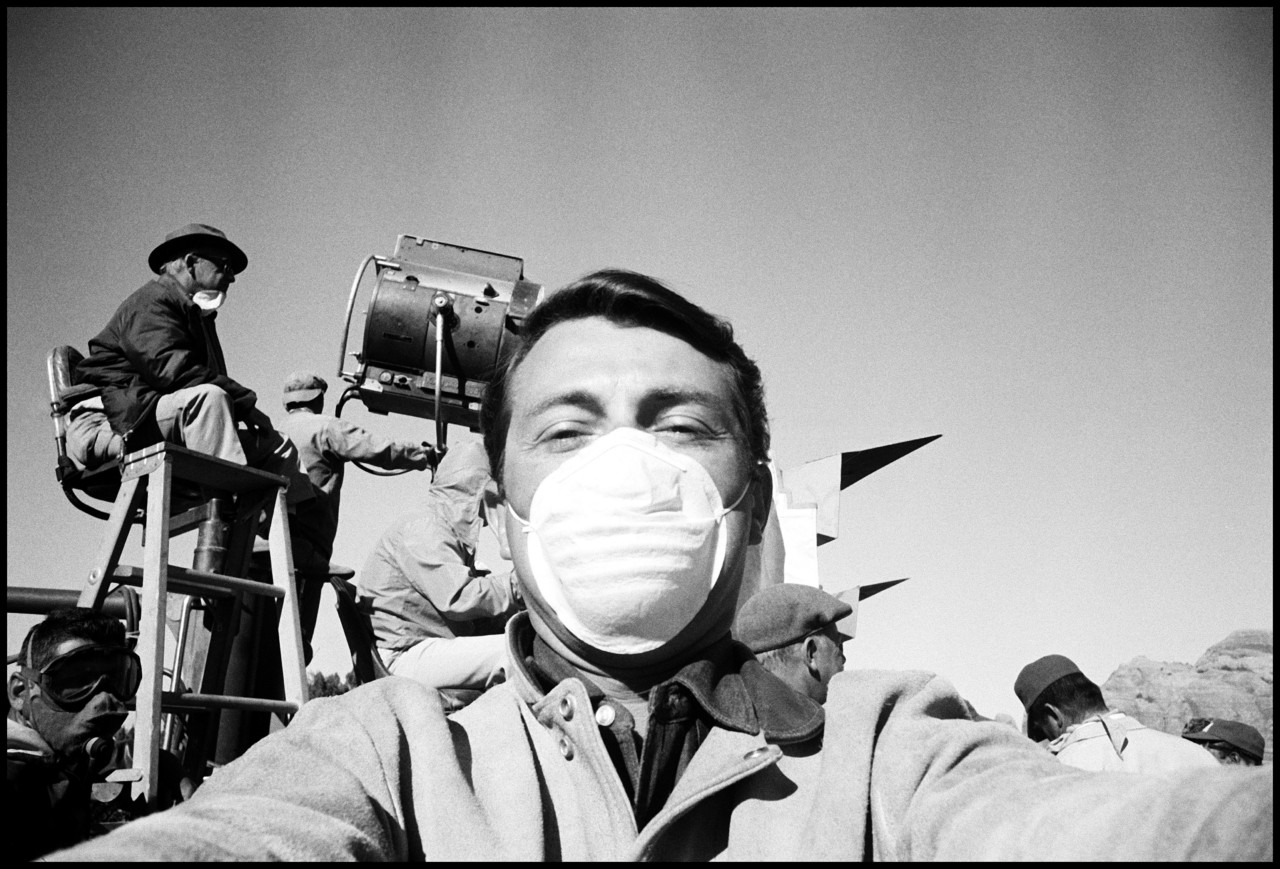

In the digital age, the ‘selfie’ has become a genre of photography unto itself. World Selfie Day (which takes place this year on Thursday June 21) is proof enough. Technological advancements and the rise of social media has meant the selfie has exploded into popular culture, becoming something anyone can partake in, and symbolic of the millennial generation. Although the term selfie was only added to the Oxford Dictionary in 2013 its ubiquitous nature has quickly meant it’s been used to describe any photographic self-portrait, but while a selfie can be a self-portrait, not all self-portraits are selfies. The two are interlinked but are part of a wider history of photographers seeking to implicate themselves within the frame.

Magnum photographers have often turned the camera on themselves; finding an enthusiastic, compliant and accessible subject in their own person. As a result, there are a myriad of ways they have approached the self-portrait, or situated themselves within the frame. The self-referential photograph can be a purely visual experiment or simple playfulness. It can be a diaristic or a subversive act. It’s these qualities that have led an intriguing number to self-document. It’s rare to find a photographer that hasn’t.

"I am present, but I want to avoid the focus on myself"

- Susan Meiselas

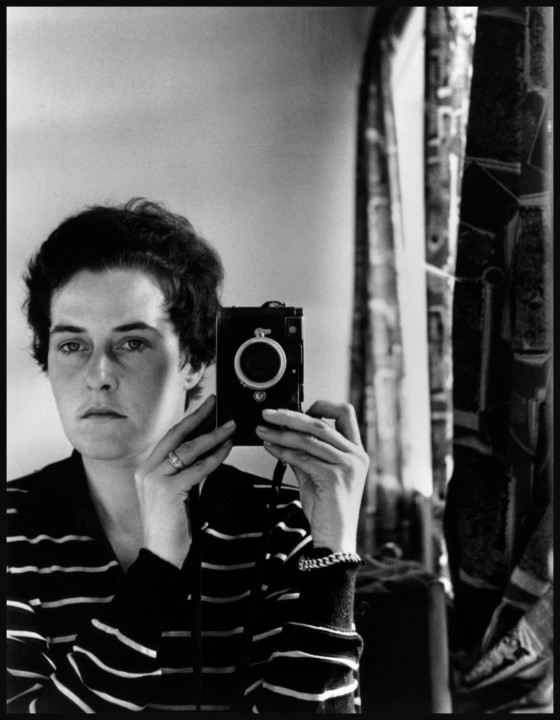

The self-portrait can be a precursory act or pivotal moment in a larger endeavour within a photographer’s practice. In a previous interview with Magnum, Susan Meiselas reflected on her early self-portraits taken at 44 Irving Street. “I wanted to place myself in the boarding house because I lived there and was present. At the same time, I felt invisible. That invisibility creates a tension throughout my work. I am present, but I want to avoid the focus on myself.” It’s these photographs that Meiselas attributes to guiding her empathetic, collaborative approach, allowing her to fully understand the responsibility as a ‘bridge’ between the subject and the photograph. As she states, “I don’t pretend not to be there, but I am not the ‘story.’”

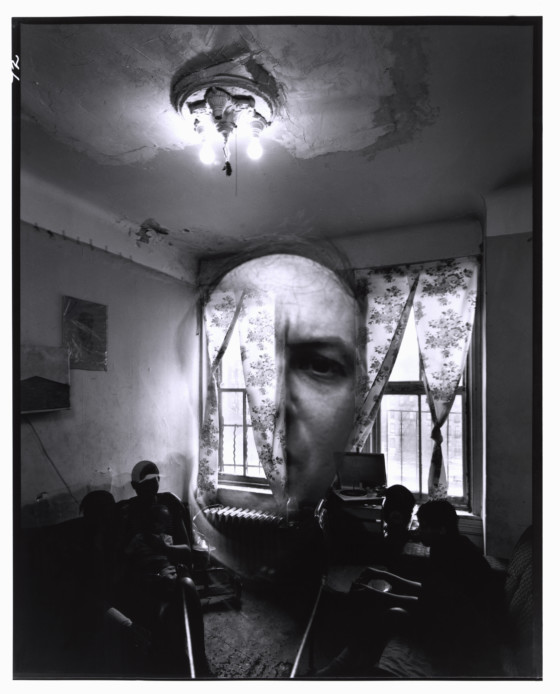

In Larry Towell’s work documenting the protests at Standing Rock, the photographer’s own body manifests as a self-reflexive link between past and present, experimenting with temporality at arm’s length. The coverage comprises of photographs taken during the Dakota Access Pipeline protests of February 2017, and the events that saw protesters reunite later that year. Towell photographs his forearm holding an image of the events at Oceti protest camp, against the serene landscape where the photograph was taken just months before. Towell believes it is most important to aim your camera outwards, hence his only interventions that place himself in the frame are to position his subjects at the centre of the story.

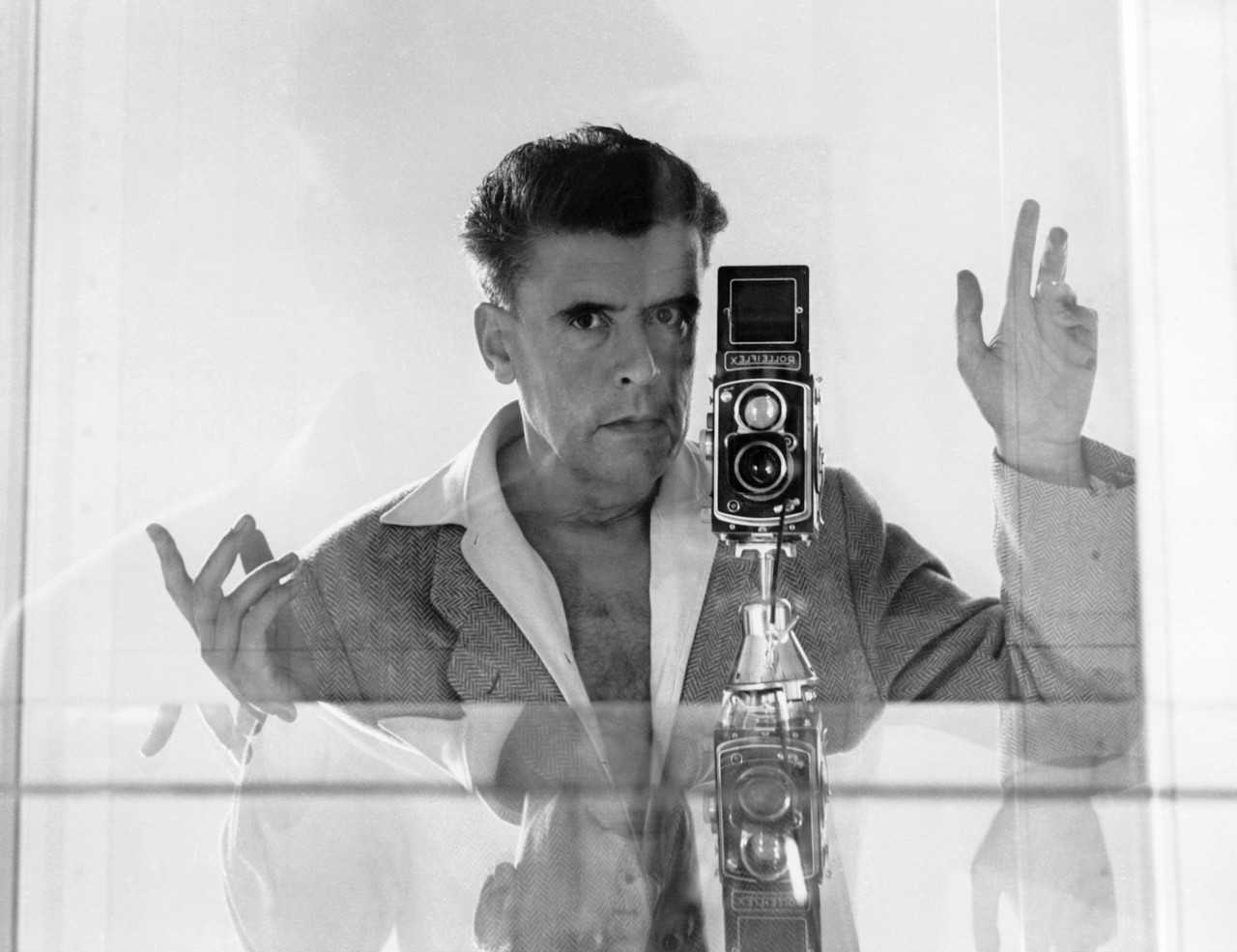

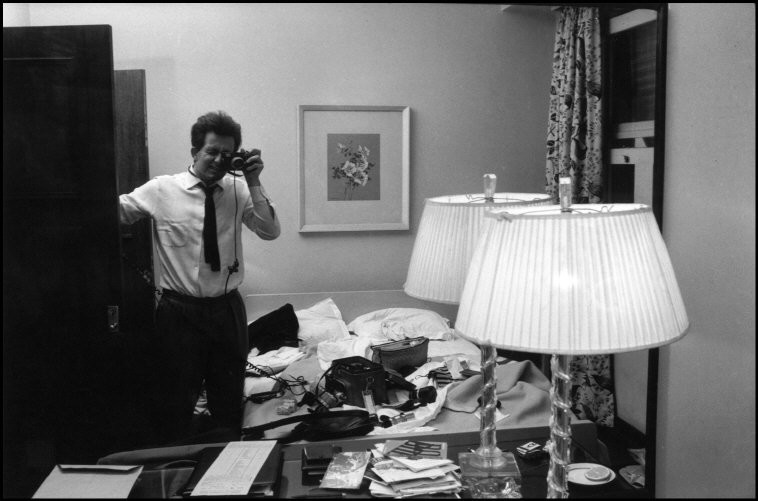

The self-portrait in a mirror is an immediately recognizable ploy, a motif that first came about in the Renaissance period with Parmigianino’s painting Self-portrait in a Convex Mirror (1524) and is still cropping up as a selfie-format on social media today. In fact, the mirror has long been used as a metaphor for photography itself. The link, established in the medium’s early days, was discussed by Oliver Wendell Holmes, who, writing in 1859, called the daguerreotype “the mirror with a memory”.

Photographers have often attempted to view themselves as others do, holding their cameras up to the mirror, at once becoming both the observer and the observed. This is an idea realized in René Burri’s self-portrait in a hotel bedroom, testing camera equipment while reporting from Sao Paulo in 1960. In Inge Morath’s 1958 self-portrait, the photographer holds a more sombre expression.

"The 'self' therefore is always in some respects also an ‘other'"

- Susan Bright

While the photographer in the frame can be linked to photographic practice, the self-referential portrait is often thought about in terms of communicating an aspect of the ‘self’ to others, or the search for an ‘authentic self’. But as Susan Bright, author of Auto Focus: The Self-Portrait in Contemporary Photography (2010) points out, the self-portrait doesn’t reveal an ‘inner existential being’ rather a display of ‘self-regard, self-preservation, self-revelation and self-creation’, open to any interpretation.

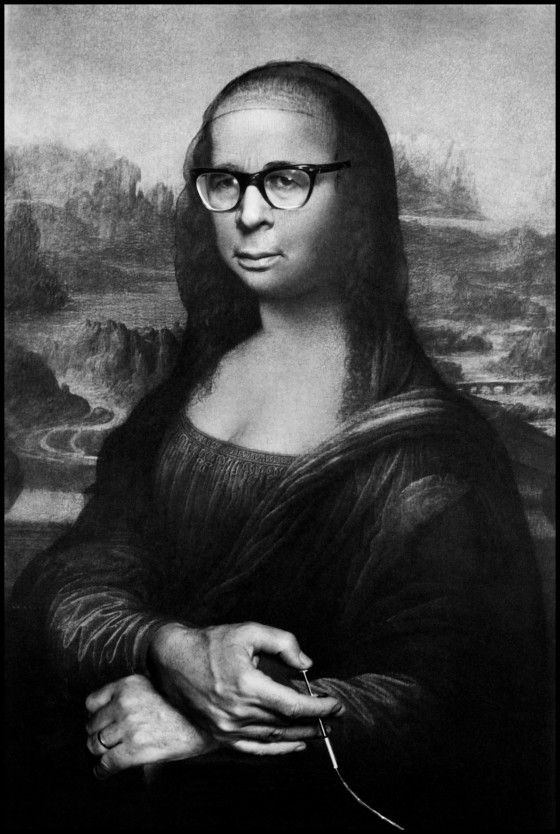

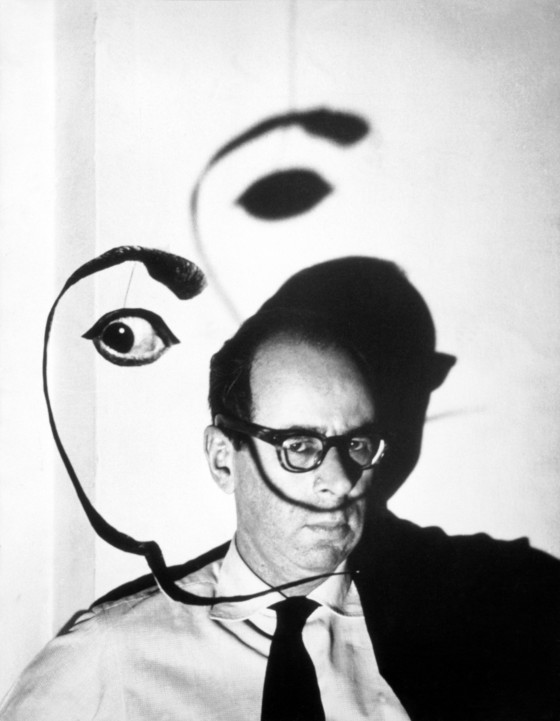

Toying with the idea of constructed identity, Philippe Halsman experimented with masquerade. In both Self-portrait as the Mona Lisa and Self-portrait as Salvador Dali, Halsman references his 37-year working relationship with the surrealist painter, which resulted in several portraits.

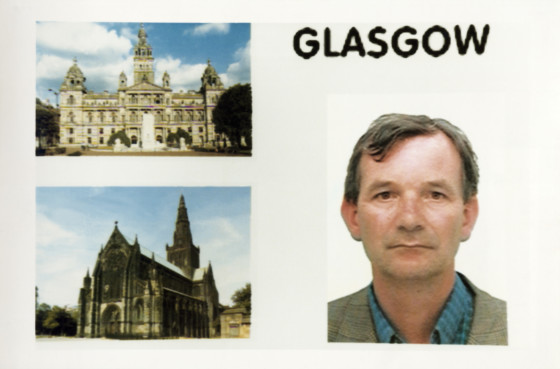

In Martin Parr’s Auto Portraits, the photographer explores the cultural histories of portraiture, using himself as a model. Whether taken by a local studio photographer, a street photographer, or in a photo booth — Parr blurs the line of identity. Characteristically ironic, the series references the awkward nature of self-portraits while riffing on their implied narcissism. In doing so, Parr also maps the trajectory of analog to digital from 1996 to 2015 revealing how technology has impacted the portrait, making self-documenting now the most accessible option for many.

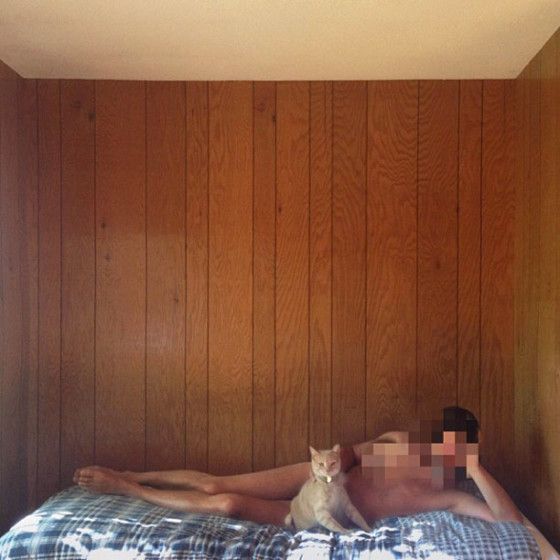

One photographer who directly subverts the selfie is Alec Soth. In an interview, he pinpoints the invention of his ‘unselfie’ when he joined Instagram. “I had a desire to photograph myself. Why? That was the big question,” he asks. In the resultant images created at this time, Soth censors his face in various ways, self-sabotaging his selfie attempts, but none-the-less documenting his participation in selfie culture.

"I had a desire to photograph myself. Why? That was the big question"

- Alec Soth

The sheer depth and scope of photographs that depict their creator points to self-portrait as an integral part of picture making, beyond that of a genre. The desire of the photographer to implicate themselves within the photograph is a visual clue as to the role of the photographer within wider society and provides a valuable insight into their individual practice. However, as Susan Bright points out: “the self-portrait is always presenting an impossible image, as he or she can never mimetically represent the physical reality that other people see. The ‘self’ therefore is always in some respects also an ‘other.’”