Magnum Nominee Sim Chi Yin Waited Years to be Able to Commit to Photography

The Singaporean Nobel Peace Prize photographer on the development of her practice and the allure of slow and researched storytelling

Beijing-based 2018 Magnum nominee, and 2017 Nobel Peace Prize photographer, Sim Chi Yin’s photographic projects straddle geopolitical political and environmental issues, devastatingly intimate human interest stories, and deeply personal familial investigations. In spite of a fascination with photography dating from her teenage years, it was not until she was 32 that Sim finally threw herself into full time photography. Prior to that she had been a history student and an award winning foreign correspondent for The Straits Times – Singapore’s English language daily. Here, Sim discusses the development of her approach over the years, the impact of a journalistic background on her work, and the circuitous route she took to professional photography.

You came into professional photography comparatively late, you didn’t study it, you were an award-winning journalist for years.

I actually started taking photos when I was around 15. I became quite fascinated with light, shadows and shapes. I was quite an intense teenager. I imagined that I had a switch in my head that I could flip and then all I would see was geometric shapes – I became fascinated with form. I used to go down to Little India, in Singapore, and practice street photography, just watching human life, light, and time intersect.

How did that early interest transform into a profession?

By high school I had become obsessed with the notion of becoming a useful person. Friends remind me, even today, that I used to say ‘one cannot be self-indulgent’. I was a very serious teenager – I’m way less serious now! I joined The Straits Times, Singapore’s national English daily, in 1997, at 18, as an intern photographer. I was there for nine months.

I was excited about making pictures and also suddenly having all these adult friends who were photographers. I was an eager beaver intern, I asked for weekend shifts. I had taken a night-class in basic photography when I was in high school, but that aside I learnt to do everything – from portraiture to sports photography – on the job, cutting my teeth at The Straits Times. I think I was the first high school student they had taken on at the photo department and they might have been pleasantly surprised that I could do more than just make photocopies and coffee!

The staff photographers would slip me books by Henri Cartier-Bresson and all these Magnum names – the classic photo books – and say, “go read this”. I learnt in the newsroom and through those books.

So what changed your trajectory, from a budding staff photographer, to a staff writer?

I won a scholarship to go to London School of Economics and Political Science to study history. While I was in London I worked as a photographer for the university press office and the University of London newspaper, and I interned at The Guardian and Independent. After four years at LSE, I finished with a master’s degree, and went back to Singapore.

As part of the scholarship, I had signed a contract to work for the paper for eight years afterwards. If I left before the term was up, I would have had to pay back all of my school fees, with compound interest. It was a huge commitment, but at 18, I thought it was the best way to get a good education and leave home.

When I came back to the paper, the picture editor who had first hired me when I was 18 and who had fought for me to get this scholarship despite my not being a straight-A student, no longer worked there. The newspaper management didn’t want me to, in their words, ‘just take pictures’. I was sent to the news desk as a writer, and was posted to China in 2007 as a foreign correspondent.

"The newspaper management didn’t want me to, in their words, ‘just take pictures’. I was sent to the news desk as a writer"

- Sim Chi Yin

I felt that in my bones I was a visual person rather than a words person. I was initially kicking and screaming when I had to go be a reporter because it’s a completely antithetical thing to photography.

With photography you are hanging back a little bit, observing the scene and then subtracting from that. You are figuring out what you want and what you don’t want in the frame. As a reporter you have to keep thrusting yourself in people’s faces, asking questions, and that was not in my personality. I was a deep introvert when I started, I have since learnt to have a work persona. I still love writing, and write for my own projects, but I’m more at home speaking visually.

Through the years, I continued with photography outside of work. I did various projects – for instance, in 2006, I got some photographer friends together and we taught a group of migrant workers to take pictures, then exhibited their work in show called InsideOut. That was an early stab at participatory photo projects. I also made my first long-form project The Long Road Home, traveling to Indonesia in my spare time to document women migrant workers’ journeys. I enjoyed embedding with people, using pictures to tell their stories, and I felt surer that I wanted to do that to be a ‘useful person’.

And what proved to be the turning point, drawing you back into photography full time?

Towards the end of my contract with the newspaper I met Susan Meiselas. She had come to Singapore to do a piece on Indonesian women migrant workers for Human Rights Watch. Because I was the go-to labour reporter at the time we met and I pitched in. We stayed in touch.

In 2009, when I was contemplating quitting my writing job, I told Susan I wanted to become a photographer. She was like, “No! No don’t do it! You have a great job, you get to travel, you get to take pictures for your own stories. That’s a luxury in this very tough industry.” I was in a pretty good position, my text-and-photo features got a lot of real estate in a shrinking broadsheet and were winning awards for the paper, but I knew I was photographing with one hand tied behind my back. At the end of 2010 I decided to chuck it all in. In my early 30s I felt that if I didn’t try being a photographer then I never would. I quit at the age of 32. That was when I really started full time photography. It was a long detour.

Susan had me apply for the Magnum Foundation’s Photography and Human Rights Fellowship, which was then in its inaugural year. I applied and became one of the first two fellows on the programme. That was life-changing. I got to study with Susan and Fred Ritchin for weeks, and spent much of the summer of 2010 in New York. It opened up a whole new world to me.

"I knew I was photographing with one hand tied behind my back. At the end of 2010 I decided to chuck it all in. I wanted to pursue this dream of being a photographer"

- Sim Chi Yin

Do you think that long detour informed the sort of photography you pursued? Maybe you benefited from having those years to focus on the work you wanted to make, and to hone skills that you use still?

When I first started full-time photography, I did what I knew how to do, which was taking a journalistic approach. I sometimes think I gave my most energetic decade to the paper and written journalism. But I certainly learned a lot: I had the journalistic chops, I knew how to get into people’s lives, how to negotiate access and get out of a hairy situation. I had to learn how to deal with the cops, how to work in closed societies like China.

Being older, more mature, also brings something different to the relationships you have with your subjects. For instance, in the project that I did on a dying gold miner in China, Dying to Breathe, the fact that I was weathered and very close in age to him and his wife, made it easier for us to open up to each other – about love, loss, family.

"The fact that I was weathered and very close in age to him and his wife, made it easier for us to open up to each other - about love, loss, family"

- Sim Chi Yin

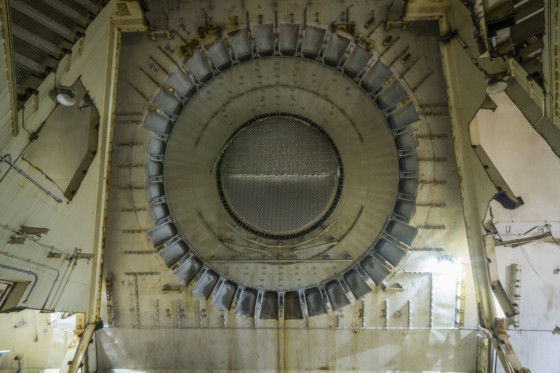

Your work has such diversity in terms of scale. From the ultra-human story, all the way up to your work on nuclear proliferation – Fallout – which is a colossal story, international and historical in scale.

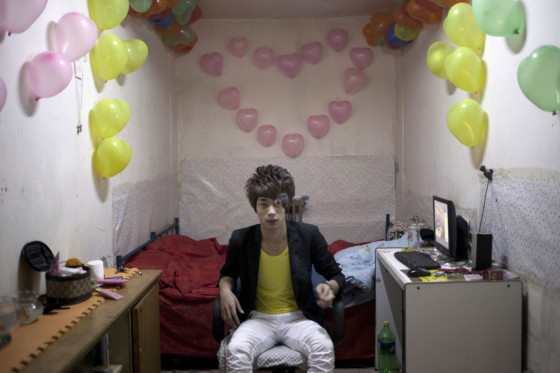

I think I like to do different types of work, and it’s been an evolution over time. I started out by doing what I knew how to do. I would go and find stories that were under-reported and that I felt were socially meaningful. Rat Tribe was my first major project, and then I went onto Dying to Breathe.

Silicosis and Black Lung were underreported in China at the time. I decided that I would find one or two character-driven stories, drill deep, and try to move people to action through the power of storytelling. The second track of the project was that I collected portraits of miners suffering from Black Lung disease shot through their X-rays. Those were more conceptual. My projects took a slightly different turn after Dying to Breathe, which was very emotional.

I think the project on which I transitioned is the family history project One Day We Will Understand. It started out as an investigation into my paternal grandfather, who we did not talk about for 60 years. I wanted to know who he was.

"I re-visited some of the places where there were ambushes and confrontations between the local Communists and the British"

- Sim Chi Yin

In the first photo I saw of him, he had a twin lens camera slung around his neck, I was like “who the hell is this guy?” I later learned that he died for Communism. I discovered that he was one of tens of thousands who were deported from Malaya by the British during this anti-colonial war. I became interested in finding some of the other deportees. Initially I searched for people who might have known him. I was intrigued by this character who had been a photographer, an editor of a newspaper in Malaya. He had a deep sense of social justice, longed for equality in society and, by many accounts, would stick his neck for his community.

I discovered more about my grandfather, found our ancestral village and house in China, and then all these layers of political and familial history emerged. As this project grew and grew it started to encompass oral histories and then I started looking at the landscape. I re-visited some of the places where there were ambushes and confrontations between the local Communists and the British. I have been photographing in rubber estates, in the jungle, in caves where the Communists hid.

The project started in 2011 and it now includes landscapes, portraits, archival, still life images, songs, video. That’s the work in which I started to transition. I started to really enjoy landscape photography and a different visual register. I started diversifying.

How did that diversification solidify over time do you think?

In 2015 I was attacked on the China-North Korea border while working and my thumb was damaged, requiring two surgeries over two years. The fact that I was injured and couldn’t work the way I was used to was a wake-up call. It gave me a chance to reflect on what I was doing, and whether I was adding to the digital noise doing the run-and-gun stuff. I decided I wanted to take a step back from that and do work that was more research-based and long-form, more intentional. Slower.

Do you mean that move to the sorts of massive and international subjects that seem to be a big part of your work now? From the international sand trade, to nuclear weapons?

There’s a geeky side of me that likes the socio-economic, geopolitical stuff — getting my brain into big topics. The nuclear was a commission, something I was asked to do, and then really got into.

The ongoing sand project started out of the fact I am from Singapore, which by UN figures is the world’s largest importer of sand per capita. I was intrigued by the fact that we don’t talk about where we get all this sand from which we use to reclaim sizeable pieces of our territory. It came out of an interest in my own country and society. I don’t know that it was a deliberate attempt to do something colossal. It became that gradually. Sometimes I wish I could attempt things less colossal!

"There’s a geeky side of me that likes the socio-economic, geopolitical stuff — getting my brain into big topics"

- Sim Chi Yin

Something that you mentioned earlier was the slowness in your work. To quote your acceptance speech for the Chris Hondros prize, it is work that is “far from the front lines and dead unsexy”. Is that slowness a critique of the current media atmosphere?

The bearing-witness type of photography is still very important. Many people are out their putting their lives and bodies at risk to do it and I salute that. I think perhaps that genre of work is not the best use of me. There are people who are way better at it.

I’m wanting to work more slowly and to try to be more thoughtful. More researched based, and more intentional. It is also a reaction to the speed at which everything happens now.

I’m not sure if ‘critique’ is the right word. It is a reaction to the fatigue of the hamster wheel 24/7 news and social media cycle. I feel that there are enough outlets inundating us with news – I’m not sure what I can contribute to that. After the thumb injury I moved to work more on commissions, exhibitions and a book. It’s been a process of evolving and experimenting. I’m growing in multiple directions and exploring more multidisciplinary ways of making, creating, telling stories. I’m looking beyond the still frame, in some ways. I’ve started experimenting with performance too.

I think we’re in the era of blending, bleeding, though of course each discipline and genre has its peculiarities and ethics. The terminology — researcher, photographer, artist — I have difficulty with. I’m just making and doing, thinking, growing! I’ve recently made a couple of portraits on a magazine commission, opened a solo show in a contemporary art gallery and am attempting a giant glass mural for a public art commission! And in October I will begin a research PhD at King’s College London. I’m hoping to bring together what I’ve accumulated up till now – going into my third career as it were — the research rigour of a historian, writing and journalistic chops, artistic curiosity, and create from there.

Also, I’ve been thinking about the difference between reach and impact. It’s great to reach millions of people through being on the front page of the New York Times, but having impact on a smaller number of people in a different form is just as valid — if not more so, in our crowded and noisy world.

I think it’s an exciting time when photography is seeking new ways to evolve, academia is keen to put out its research in visual forms, and some sectors of contemporary art are seeking more content to go with form. I’m happily confused, and exploring, learning and experimenting in this state!