Together, Alone: Jean Gaumy Discusses Solidarity and Solitude as he Joins the Académie des Beaux Arts

An in-depth interview with the French photographer, to mark his joining the prestigious Académie des Beaux Arts de l’Institut de France, dwells on his route into photography as well as the paradoxes and complexities of the genre

Jean Gaumy, a Magnum photographer since 1977, was – on 10 October 2018 – elected as a member of the prestigious Fine Art Academy (Académie des Beaux Arts) of the Institut de France. To mark his joining the Academie, here we reproduce in translation an in-deapth extended interview between Gaumy and Regis Defurnaux, which was previously published in the French photographic magazine 6Mois.

Régis Defurnaux was born in 1976, and photography has been part of his life since his grandfather offered him a camera when he was 12. He taught Philosophy of Sciences and Medical Anthropology at the University of Namur before becoming a documentary photographer.

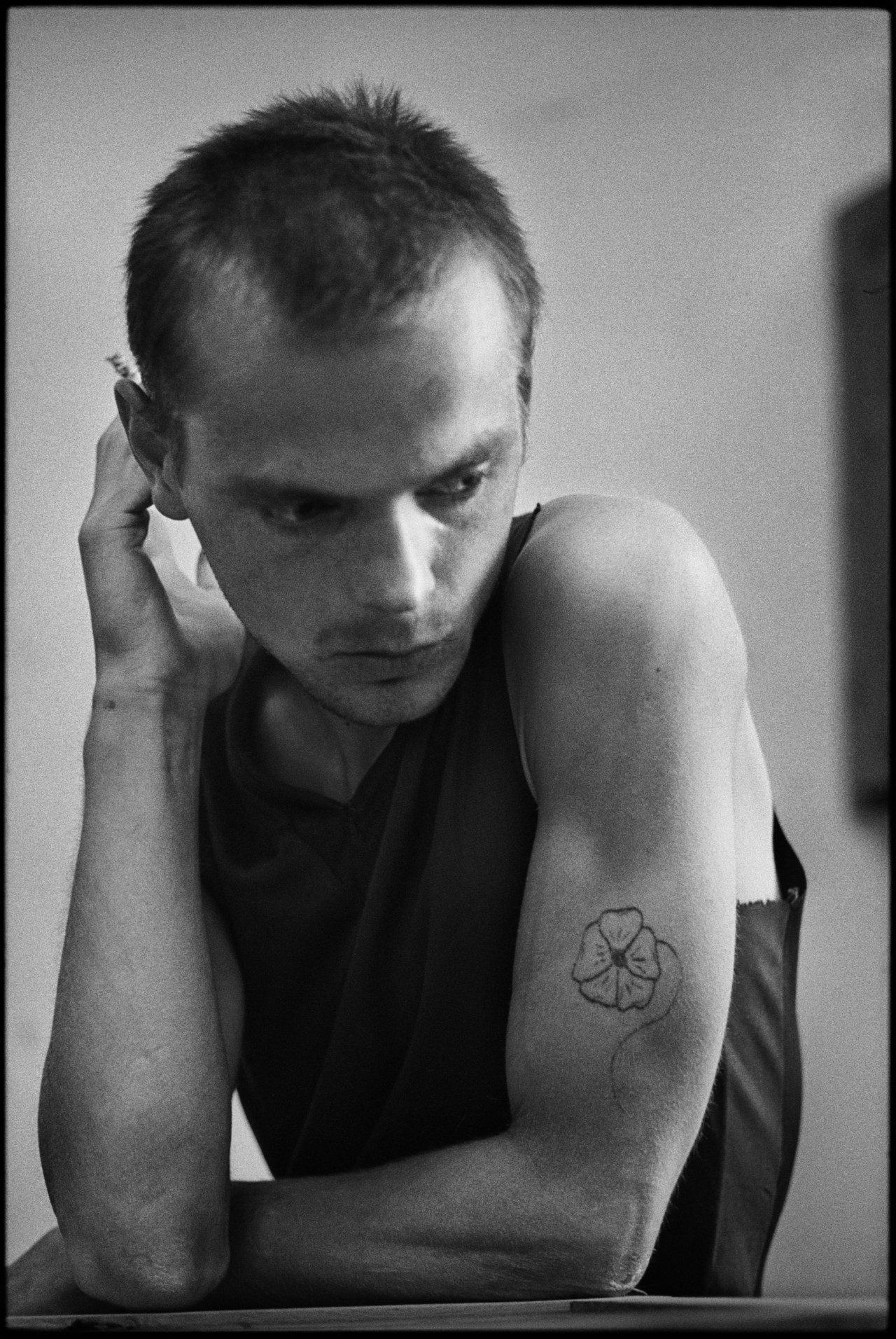

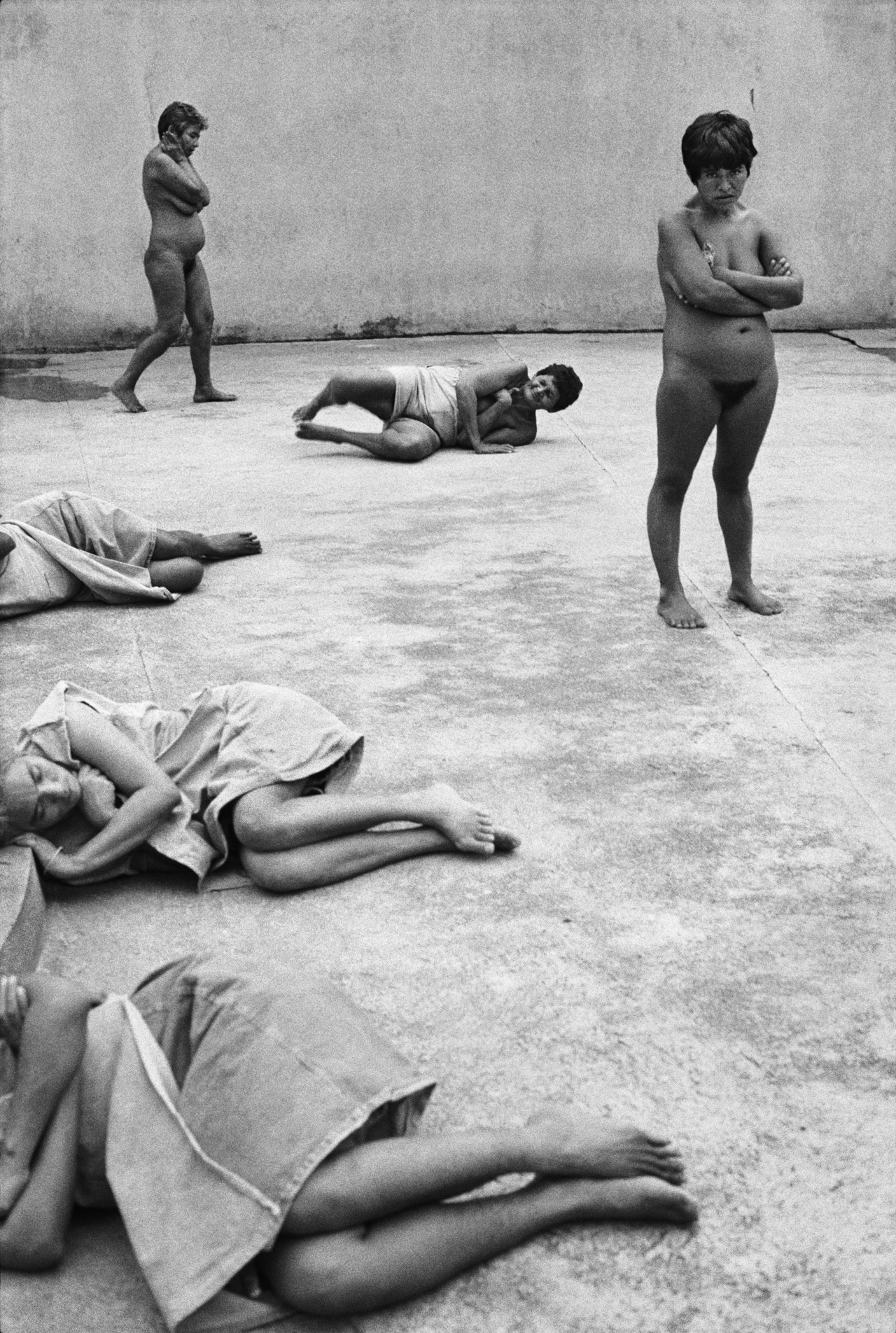

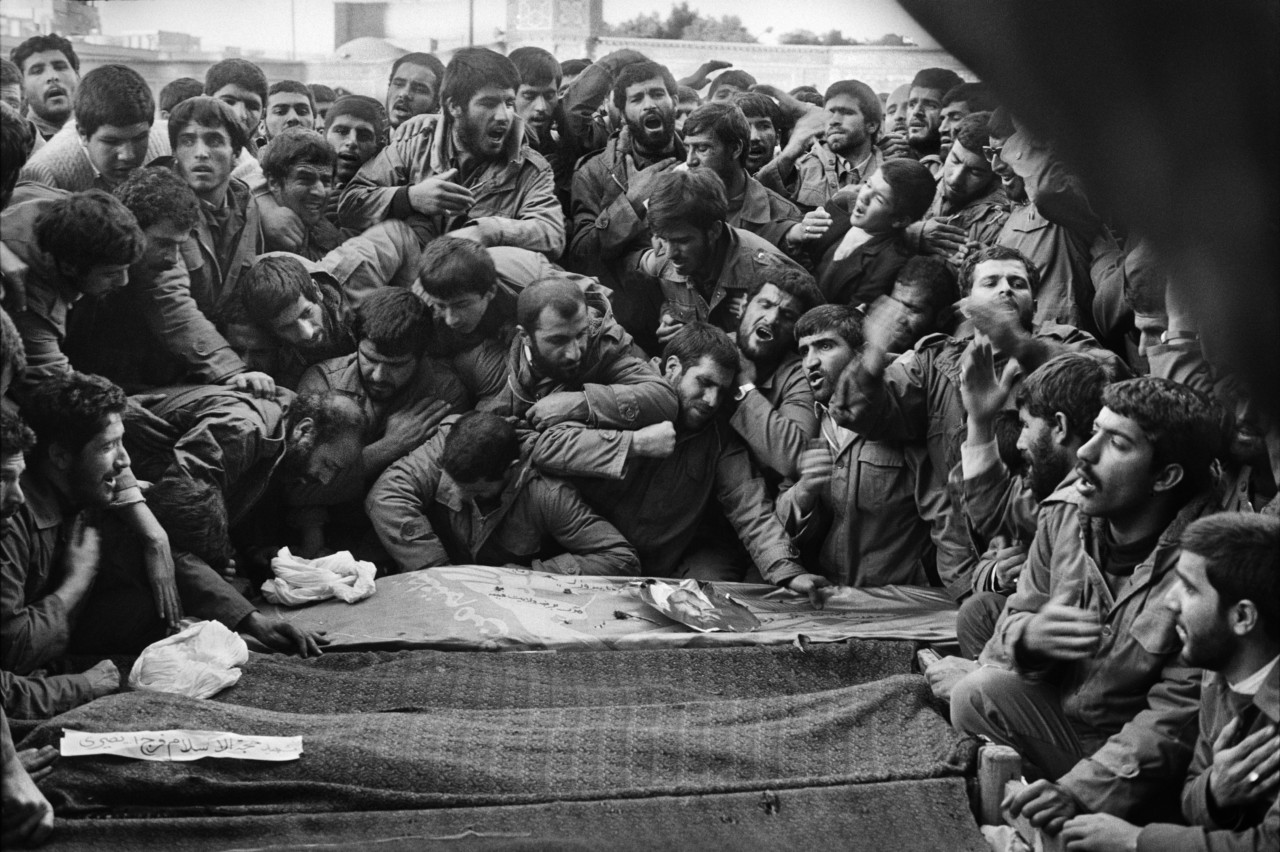

Prior to joining Magnum Gaumy had made groundbreaking projects, on the French penal and healthcare systems – two areas previously unexplored in contemporary documentary photography. Gaumy’s famous longterm projects on the fishing industry, as well as his famous work in Iran, both required the photographer to engage, on a physical level, with his subjects – a key aspect of his practice, and one he explains at length here, alongside musing on the traps set for us by technology, stereotypes, and preconceptions.

What are the first images you remember?

I feel like I grew up between the 19th and the 20th century. My grandparents took many family photos, in an early 19thcentury style : very staged, like Juliet at the window and Romeo below with a guitar. These photos interested me, they were the evidence of our family history. Where do we come from? What is our place in this genealogy, in society? Each time I go back to those albums, I look at them differently. In actuality, I recall few of those moments, they are something like a family myth, passed down from generation to generation. Now, I am doing my part. I take a lot of pictures of my family, my wife Michelle, my daughter Marie, her children…

How did you discover photography?

I was 10 or 11 years old, living in Toulouse. The owner of a shop called Place des Salins lent me a Brownie camera and developed my first rolls of film for free. I photographed police dogs training at the Salon des arts ménagers, near the Garonne river. But, for the boy I was at that time, sound was just as important as pictures. Radio broadcasts fed my imagination. I listened to the “Strange Theater”, or the Sherlock Holmes investigations, with the incredible, barbaric organ that opened the show. I was trying to create my own stories and actually wrote a few. At 15, I borrowed my father’s Grundig TK27 recorder. It’s was a way to engage intimately with the world around me, as I would with photography later on.

"The important thing is to know who you are, where you are, to be lucid, and to not lie to yourself. Every photographer must expect serious moments of doubt"

- Jean Gaumy

When did photography fully captivate you?

It started to gently interfere with me during a crossing of England on a motorbike. I was 17 years old and I recorded my wanderings on film with the same intentions as I had for the sound recordings before: to stop time, to keep track of it. Later, I sold my Mobymatic motorbike – a blue one with a rectangular headlight – to buy a Russian Zénith 24×36 camera. At 19, I felt this rage within me which I used to overcome my natural timidity.

While studying literature I worked as a freelance photographer for Paris Normandie, in Rouen. It was real on-the-job training, learning from photographers I respected. I also worked elsewhere, taking wedding photos, for example. This all paid for my studies, and I knew instinctively that it was with photography that I would make my life. I also started working on new, longer projects. Around me or in college, no one was really photographing like that at the time.

I was eventually spotted by Raymond Depardon, who I met with on the advice of Hugues Vassal and Robert Pledge [then editors of Zoom magazine]. I joined Depardon’s Gamma agency in 1973, and I felt like I was joining a Formula 1 team. It was an intense, dazzling moment. I immersed myself. Later, during a presentation at Arles Festival, I was spotted by Marc Riboud, Bruno Barbey and René Burri – which led to my entering Magnum in 1977. Looking back, I think it may have been a bit early for me, I was barely 29 and probably didn’t have enough experience.

At Magnum, the collective selects new members on their visual potential and means of framing, but also on their determination and their tenacity in conducting personal projects. You really had to know what you wanted to do.

Being a young photographer at Magnum in those years, was it a dream come true?

That is the cliché, but the reality was very different. I slept in hotels without comfort – the inverse of the myth of the ‘great reporter’. I did not have a lot of money – I was stressed all night then on assignment the morning. I had to persevere. Sometimes there were beautiful encounters, and I made strong photos, when that happened it revived me.

During that period my wife Michelle was seriously ill, I continued to hang in there, producing work, pushing myself. I felt pretty confident about my pictures, I knew instinctively how to approach a situation, almost anticipating it. I went through a period of photographic turbulence but, fortunately, I had the trust of some of my colleagues.

How did you weather that whirlwind period?

I never let go, the essential thing is to remain determined. I was not a great marathon runner, but I always wanted to finish the race. Like many others I was forced to find my second breath. I shot project after project at my own pace. I was aware of my own limits: I quickly realized that I am not really a journalist: I detect situations, I analyse them intuitively, but I do not have the wit of a journalist.

The important thing is to know who you are, where you are, to be lucid, and to not lie to yourself. Every photographer must expect serious moments of doubt. I have seen some great photographers questioning themselves in the solitude of their hostel rooms. Tenacity, stubbornness, holding on to the physicality of the work, being anchored, following one’s own convictions, to allow oneself to be impacted by the work: that is everything for me.

You have been a member of Magnum for more than 40 years. How do you explain such longevity in an ever-changing media world?

Magnum is a pretty loose group, but it is also a group with a collective intelligence that still amazes me. For me, Magnum is like a submarine: autonomous, silent, rather discreet and resistant to pressure. There is the myth of course, which the founders handed down to us, but we are rather lucid about our collective – and individual – weaknesses. We know, for example, that our gaze is historically Western, and we seek to open ourselves to other points of view. We also know that nothing is ever guaranteed, and that’s good! I sometimes wish I could learn to perceive things differently, to mutate my own visual culture. Not easy!

Photography is everywhere, how can we cope with this “tsunami of images” taken daily?

This wave surprises me. I think we are missing some fog lights, or to push the metaphor further: we need a strong windshield to resist globalization and its consequences: the excesses, the flattening of everything. The images of today are mainly used for consumption, this new God of which we are the children.

The challenge of reading images is essential: visual literacy. To maintain a certain common sense and some lucidity you need a good rear view mirror, to keep an eye on our history. What is the past preparing us for?

Each assignment is like a forest of clues of which we can report only a few branches or twigs. How can we know that we have seen well?

It is for this reason that I think that objectivity does not exist. To document reality is not to show reality. One can never touch the world, it is beyond us. We can only document it. It is not the eyes that see, but sensitivity – or the heart. We are at the will of total subjectivity, and that’s good. What matters is to say something about the world, to have a point of view, to be an honest and sincere photographer.

"It is a question of finding the right distance. There is an animal side to photography, a state of alertness. We are a little like cats, caught between instantaneousness and contemplation."

- Jean Gaumy

Reading your book Men at Sea, I could almost feelthe life of those sailors. Yet, I was not there and will never be. How do we cope with the coupling of presence and distance one experiences on assignment?

My physical distance, when photographing people, is usually between 3 and 5 meters. Sometimes less. I feel like I’m in the middle of subjects, among them, yet at the same time I’m not really present.

The contradiction is there: I am an observer. My mental and physical behaviour naturally sets me apart. This situation is unique to photographers. I have an expression: “All alone together”. It stems from a word that I like a lot, coined by Robert Charlebois, “solidaritude”, a contraction of solidarity and solitude. Solidarity is at the heart of my work. One day, I was in a mountain hut with Occitan friends and one of them, a snowplough driver, said to me, “It’s weird Jean, you are with us, but at the same time, I feel you are far away.” It’s the curse of photography.

If we get too close to people we lose accuracy in our work. It is a question of finding the right distance. There is an animal side to photography, a state of alertness. We are a little like cats, caught between instantaneousness and contemplation.

How would you describe empathy, in your work?

It is sometimes too present. As my contract with the others is silent, my attitude and my work speak more than me. I recently took pictures at the foot of the cliffs of Fécamp, Normandy, a very isolated place. In such moments, I am alone, left to myself. Nothing matters but the contemplative aspect and the shooting. Then, a few hundred meters away, a hiker appeared. Suddenly, my behaviour changed, I went back to another mindset, a twinge of empathy.

That’s what you have to manage. It makes me think of the last Martian on Mars in Bradbury’s book Martian Chronicles, he becomes crazy, being driven by the expectations of the others. Under the cliffs, I was just trying to be alone.

If one shows, through a bodily stance or attitude, through a physical engagement with taking photos, then subjects react to that. Guy Le Querrec speaks about it in his book “Lobi”. In bullfighting, this is called el dominio. In documentary work the success of an image depends as much on the photographer as on the person photographed. There is a shared intelligence in the photographic act, a very fast and very subtle exchange.

"In documentary work the success of an image depends as much on the photographer as on the person photographed. There is a shared intelligence in the photographic act"

- Jean Gaumy

The photographer is an actor almost?

Yes. It’s obvious and important – we play. I try to integrate my movements into situations, I improvise, I test, I show an interest in people. It’s all about knowing and controlling how I will be perceived. It’s a question of balance.

In Iran, I made people laugh. It was unexpected, and that was exactly what I liked about them: that happy side, a little bit schoolboy or teenager. Everything lies in that relationship between photographer and subject. It’s about having a presence, and not reducing people’s life to a show.

In photography, the spontaneity of the body is essential. It’s an attitude. Sometimes we shoot to motivate ourselves. We frame constantly, even without a viewfinder at times. On a contact sheet, one can see this movement, the intentions of the photographer. It’s a predator’s behaviour. We home-in on the frame that is tightening.

Technological advances in photography follow one another at the rhythm of the tides. How do you experience these updates?

The blind adoration of technology, in some, conceals – quite badly – a lack of sensitivity. It is wrong to reduce photography to technology, to pixel soup or post-production games. When I use technology, I remain a kid. It’s fun, I take what interests me – the possibility of finding echoes of my childhood movies, for example. But whatever I do, I am the one deciding.

Do you use your smartphone?

I do. At first, only for scouting. And I must say the transplant took. In fact, the photographs made on the Smartphone stimulated me. But I want to be cautious, it is so easy to bluff others on the cheap, and to lie to oneself. When I started using digital, I disciplined myself. With the Smartphone, I stick to black and white and a single digital filter formula. I refuse the random proposals of the machine, I want to use this technology in a moderate dose. It’s important to keep one’s eye free.

How do you feel about the cross over between cinema and photography?

These two worlds are complementary. I would say we pass from one to the other. Between filming and photographing, there is the same tense relationship as between black and white and colours. When I started making films in the 80s, I had recurring dreams of photos that came alive, in a loop, for a few seconds. Later, in a gallery of the Arsène Lupin Museum in Etretat (in Normandy), I saw a moving still picture. It was the early beginnings of virtual images used in museums. It was a shock, it was a sudden, real-life visualisation of my dreams … I like the in-between, this form of ambiguity suits me.

How do you escape the trap of the postcard?

By using a paradox: you have to drop your luggage and –simultaneously- take it into account. I am currently working on the Cordouan lighthouse in Gironde, for which I am trying to reject stereotypes. I fight with images of storms: Victor Hugo, Rachilde, Gustave Doré, the popular mythology of the lighthouses and their lonely guardians, the French TV show “Thalassa”… This project is actually one of the hardest I have done: I am battling myself.

We can’t eradicate our past, our history, our references. We can’t cut loose form everything that constitutes us. I believe we can be nostalgic, and curious about the future. It is a question of being cautious about our roots and curious about the metamorphoses to come. Again: what is the past preparing for us?

Is photography a universal language?

When I was 14, at school, I pointed out to the teacher that colour – blue for example – is probably not perceived in the same way by everyone. Everybody laughed. It was naive intuition, and yet! We have five senses. They are not calibrated identically. Our perceiving equipment is rather basic when we turn it upon world.

You do not like being categorized as an artist, I hear you prefer the word “author”.

‘Artist’? That word is so over-used and depreciated. Everyone today claims to be an artist, all equals… What’s going on? I’m a photographer, that’s not so bad, right?

Your question reminds me of one that comes up regularly when I show my work in Paris: “But finally Jean, are you an artist, or a photographer?” It’s terrible, this need to label people. When I was considered a photojournalist, a museum dismissed my maritime photographs for a collective exhibition on the theme of the wave. For them, it was clear: I could not be an artist.

Talking with you about photography I have the impression of being caught in alternations.

Yes. Kind of. Shadow and light, chiaroscuro, Past Future, Science Fiction… These contrasts attract me. The contradictions fascinate me.

What is next for you?

I still want to catch reality. Tomorrow? It will most probably be one or two other documentary movies, probably also landscape photographs. I want to try to visually capture the bubbling of nature. And come back to people too. To drag, to walk, to be silent, to live and to photograph the poetic bitterness of this world.