Afghanistan: A Personal Homage

Chris Steele-Perkins reflects on experiences documenting the cycles of wonder and violence in Afghanistan from 1994-1998

Afghanistan is a book by the photographer Chris Steele-Perkins in which he created a profoundly personal homage and celebration of Afghanistan, a place he visited numerous times in the course of five years, from 1994–1998.

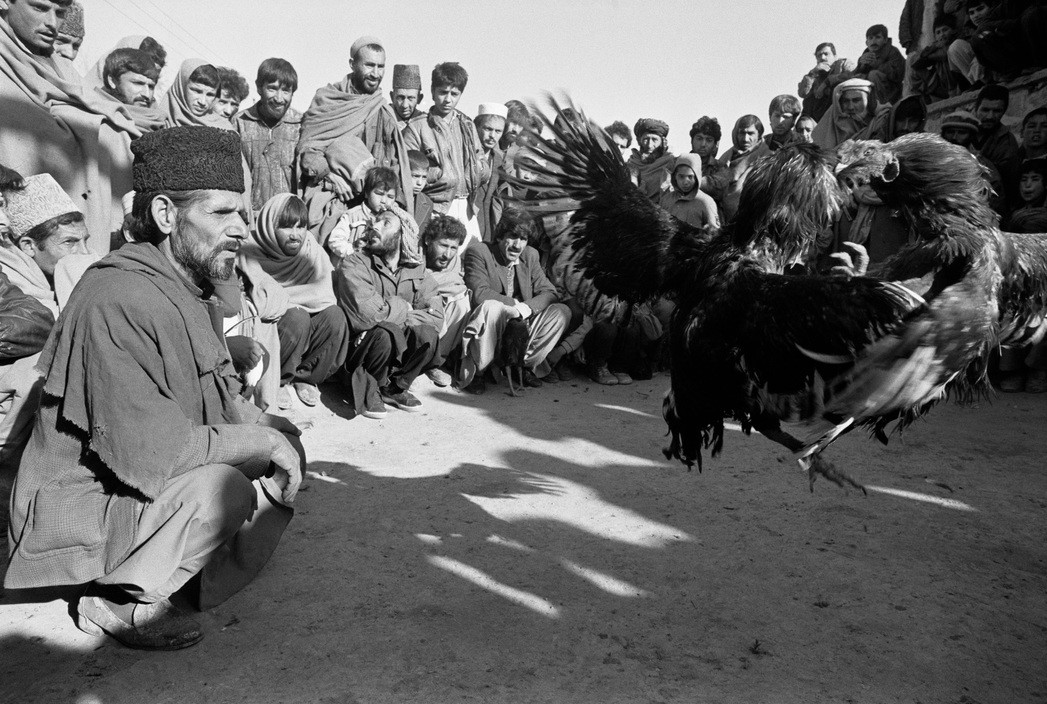

Steele-Perkins has sought to capture the continuing cycles of everyday life despite the reality of war, resulting in a collection of images of wonder and violence, terror and joy. In order to do justice to this long-suffering country, Steele-Perkins felt the appropriate response was not a book of photojournalism, but a photography book that transcends journalism.

His message is one of hope and as a result, the photographs are unforgettable rather than sensationalistic. Excerpts from the masterpiece of the greatest Afghan writer of the 20th century, Sayd Bohodine Majrouh, are woven throughout the book. Steele-Perkins’ reflections feature in the publication. In these, he remembers individuals he encountered during his work. Below, we share extracts of these reflections.

—

Kites were flown on the outskirts of Kabul. Some were elaborately decorated as birds, others were simple pieces of paper or plastic on a crude wooden frame. Small blades or broken glass attached to the string near the kite would cut rival fliers‘ strings as the cords crossed. As the severed kites limp down from the sky, children and grown men tear across the field with long sticks with hooked ends, chasing the falling kite, and compete to capture it from the air before it touches ground. The kite then belongs to the capturer, who will fly it himself or sell it.

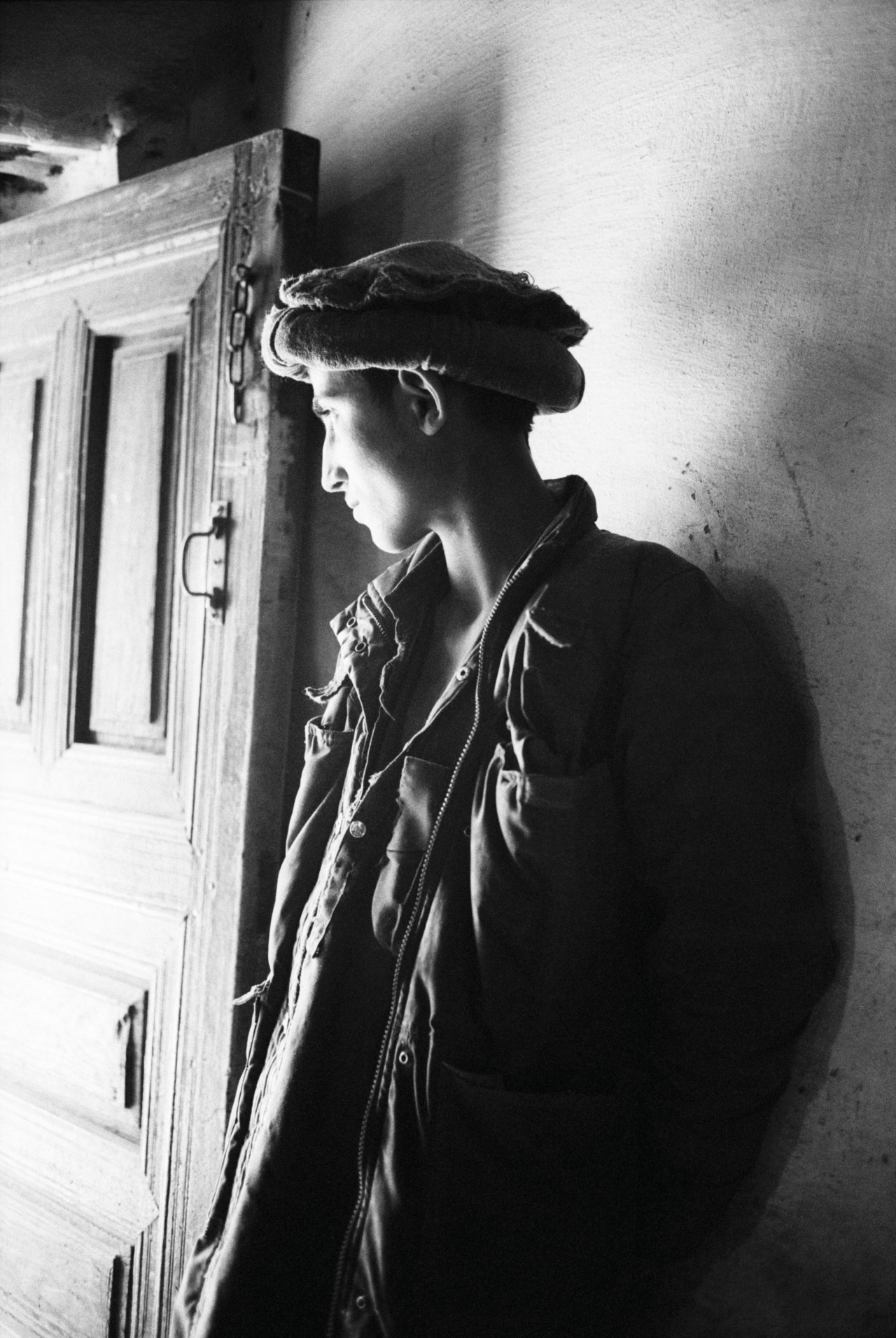

"It was heroic, beautiful, violent, twisted, gracious, and tragic. The experience of being there works its way into one's being; an infection of the soul demanding that you return.

"

- Chris Steele-Perkins

—

A young man is playing a recorder near a battered anti-aircraft gun that seems to stand abandoned beside a field. He is a little simple. He plays the same tune over and over again. I photograph him and he keeps wanting to shake my hand, again and again, like the tune. I ask him what he does. He is the anti-aircraft gunner.

—

The Taliban hold the airport. We ask for permission to photograph. A young mullah comes out of a building. He is barely in his twenties : soft over-fed body and chubby, creaseless face. He can know nothing about fighting, yet he is in command. He gives us permission as long as we do not photograph the soldiers, and then disappears inside again, unconcerned over whether we follow his instructions. A battered truckload of young men pulls up and they tumble out covered in dust from their journey. They are new volunteers we are told, straight from the Madrassas, the religious Koranic schools. ‘We have come to fight for Allah,’ they all proclaim. A rusty container is opened which contains an armoury of automatic weapons ; old AK47s already ruggedly used. They all surge forward as the weapons are distributed. They are unsure, handling them awkwardly, feeling their weight, fumbling to take the clips off. Some stick flowers down the barrel. They laugh nervously and scramble back on the truck, wave their weapons in the air. Now they are men. Fighters for Allah.

—

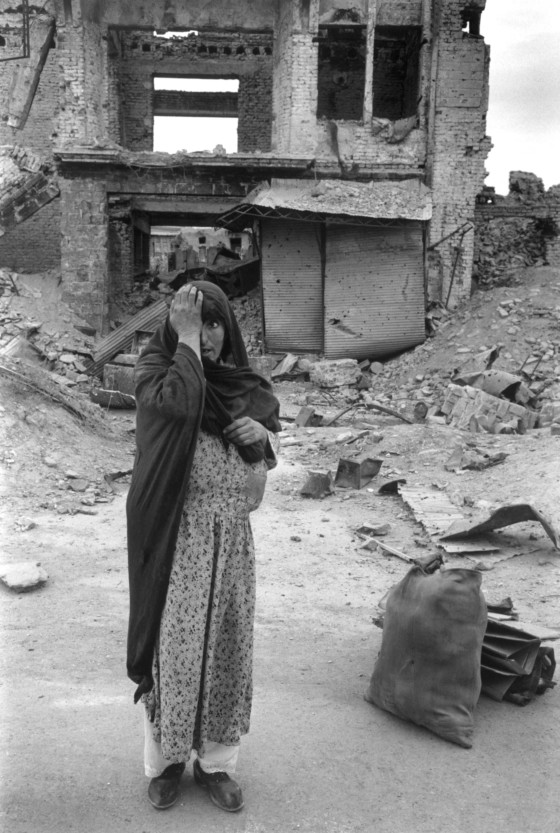

I teamed up with Julian, the Sunday Telegraph correspondent in Delhi, and Abdullah, an Afghan photographer with AP. Abdullah was captured by the Russians and held and tortured by them for two years. Many of his friends and family were killed by them. After they left, he worked as a driver for press and TV crews. AP asked him to set up the Kabul office, and there he learnt photography. Since then he was told to leave Afghanistan by the Taliban, who did not like his reporting, and now he lives as a political exile in Spain. We wanted to go in for longer than ten minutes and discussed taking a donkey and walking. But the press scrum was subsiding and the fact that we did not want to come back with the helicopter seemed to make it easier to get on a flight, which left us in the village of Behka. The village had been totally destroyed. There were about 1,500 people here and about 400 had been killed and 1,000 animals lost. I walked around photographing and talking to some people through Abdullah. Whole hillsides came down, engulfing people and homes. The evening sun raking across the utter destruction of the village bathed the scene of loss and despair in a liquid beauty. Nothing was left standing. Men were shovelling dirt from the remains of their dwellings to salvage the odd pot, the unbroken glass and, above all, the wood which they could use to start rebuilding their lives.

To spend the night we chose a spot on a hilltop that had survived the quake without falling away at the edges. It seemed solid; somewhere that had withstood the previous shock.

We were behind a white Red Cross tent erected by an old man and his family. We asked if he minded us sleeping in the field behind him, a field sprouting a host of bright red poppies, redder still in the evening sun. He said, ‘Welcome.’

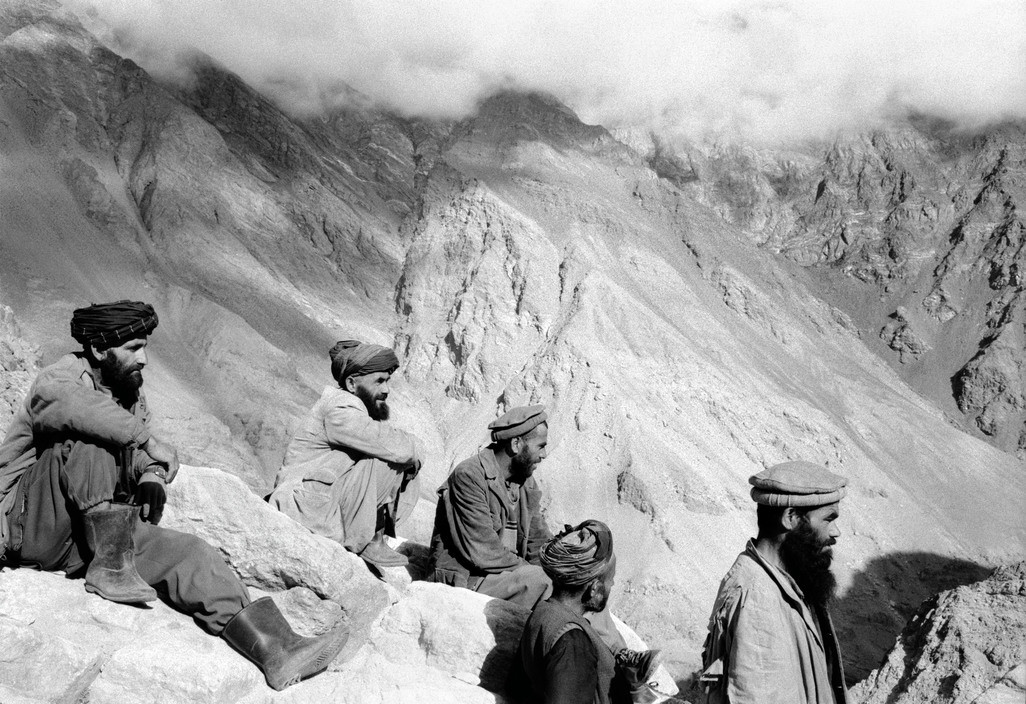

After we had laid out our sleeping bags on a plastic sheet, the village head and a group of elders came up to sit with us for a while. The head was a farmer, like all the rest. He had lost many of his sheep in the mudslides caused by the quake. Like the other men, he was a part-time fighter. He would take his gun when he was needed and then come back and resume farming. None of them seemed troubled by the Taliban, who they stated would never come there. Whether they believed this or not I could not tell.

As dark came they drifted away, having offered us a guide in the morning to the next village. The old man in the tent came out carrying a carpet that he had salvaged from the ruins of his house. He insisted on laying it down beneath us. He had lost almost everything, his life had literally been turned upside down, and yet he insisted that we use his most valuable possession. Shortly afterward he appeared with tea and bread. He would not allow us to refuse. We managed to force him to take some sweets and biscuits from us in exchange. As he and his son sat with us and the tea warmed the chill of evening and the stars started to jewel the sky, the low murmur of conversation between Abdullah and the old man and his son was the only break in the vast silence of that place. I was close to tears at the beauty, the sadness and the generosity of these people who had lost all, yet still, without expectation of return, had something left to give to strangers.

The mountains profiled around us in a ring, with us at the centre. So many stars never seen in murky Britain. I lay on my back to take in the glory of the infinite heavens and to wonder how such aching splendour could exist when below us lay the destroyed village, the dead and the bereaved. I thought : one day, when there is peace in this country, in the springtime when there is green on this hard land, I shall bring my sons here. We shall hire donkeys and walk through these villages, stay in places like this, break bread and drink tea with these people. One day.

At about 3.00am, as the cold was biting through the sleeping-bag, a tremendous tremor, or so it seemed, moved right through my prone body. Panic, an instinct to run. Where? Breathe deeply, lie back down and wait. You have no power to do anything else.