“It always has to come from the Inside”: Bruce Davidson’s Retrospective

Curator, poet, and photography historian Carole Naggar reflects on the photographer's career-long pursuit of the long-term documentary project

In 1949, sixteen-year-old Bruce Davidson won the Kodak High School Snapshot Contest (animal division) for his picture of a baby owl taken at the Trailside Museum in River Forest, Chicago, Il. He sometimes dreams of going back to his old neighborhood. The owl would ask, “So, where are those prints you promised me?”

Unfortunately for the owl, Bruce Davidson has been too busy. A traveling retrospective made up of 190 pictures made between 1955 and 2008 – now opening in Monschau, Germany – demonstrates the extraordinary range of his achievements since he started photographing seventy years ago.

Part of a generation of documentary photographers who emerged in the 1960s such as Danny Lyon, Lee Friedlander and Diane Arbus, Davidson joined Magnum Photos in 1958. But his early essays like The Walls (1955) and Widow of Montmartre (1956) already showed his deep empathy and strong sense of composition.

In 1955, Davidson, drafted into the U.S. Army, was sent to Fort Huachuca, Arizona. On weekends he hitch-hiked to Mexico, and by chance flagged down an old Model T Ford. The owners, an old couple, the Walls, took him in and he stayed with them on weekends. Unguarded and open, they let him into every aspect of their lives. Focusing on the everyday choreography of tender gestures between spouses, steeped in deep shadows, lyrical and melancholy, the photographs are unusual for their sense of closeness, and also prefigure the method Davidson would come to use throughout his career: the telling of a story slowly, in-depth, in a series, rather than with emphasis on an individual image. In Davidson’s choice, to pursue the long term project, he followed one of his masters, W. Eugene Smith.

"I am attracted to very elderly people"

- Bruce Davidson

“I am attracted to very elderly people,” Bruce once confided in me, “[The Walls] was a prelude to the Widow of Montmartre photographs, which I did next.” In 1956, he was posted to the Paris suburbs, and on his new scooter drove into town every weekend. Through a friend he met Madame Fauché, the widow of the Impressionist painter Léon Fauché who lived among the paintings of her late husband in a Montmartre garret with a skylight that framed the Moulin de la Galette. She had known Toulouse-Lautrec, Renoir, Matisse and Gauguin, and through her Davidson felt he was gaining access to the memory of a lost past. He followed her hunched, black-clad silhouette in her daily rounds in Montmartre’s streets, or photographed her face, gently illuminated by the dusk’s rays that filtered through the skylight. In these thoughtful images, it seems as if the accumulation of art and everyday objects in the narrow space reflect layers of memory, bringing past into present.

Getting in from the outside, entering someone’s life and through time becoming an insider, is something that also took place when Davidson photographed Jim Armstrong, a dwarf working in a New Jersey circus. While he did photograph Jim at work, the most striking images were made before and after Armstrong’s act. Holding a cigarette and a bouquet of artificial flowers, he stands in a muddy alley in his Derby hat and suit; or, his face free of makeup and heavily lined, he sits alone at a diner table while onlookers in the background gawk. Davidson also captured a remarkable picture of Armstrong sleeping in his tent, behind a towel that hangs like a makeshift curtain. Such an intimate setting makes us fully grasp his humanity. “We are all dwarfs, either physically, mentally or spiritually.” Davidson told EsquireMagazine at the time. “In photographing Jim Armstrong, I was photographing the dwarf in all of us.”

With these deeply emotional images, Davidson brought the idea of the outsider into the public’s attention. Danny Lyon, Larry Clark and Diane Arbus, among others, would later on pursue this theme.

"In photographing Jim Armstrong, I was photographing the dwarf in all of us"

- Bruce Davidson

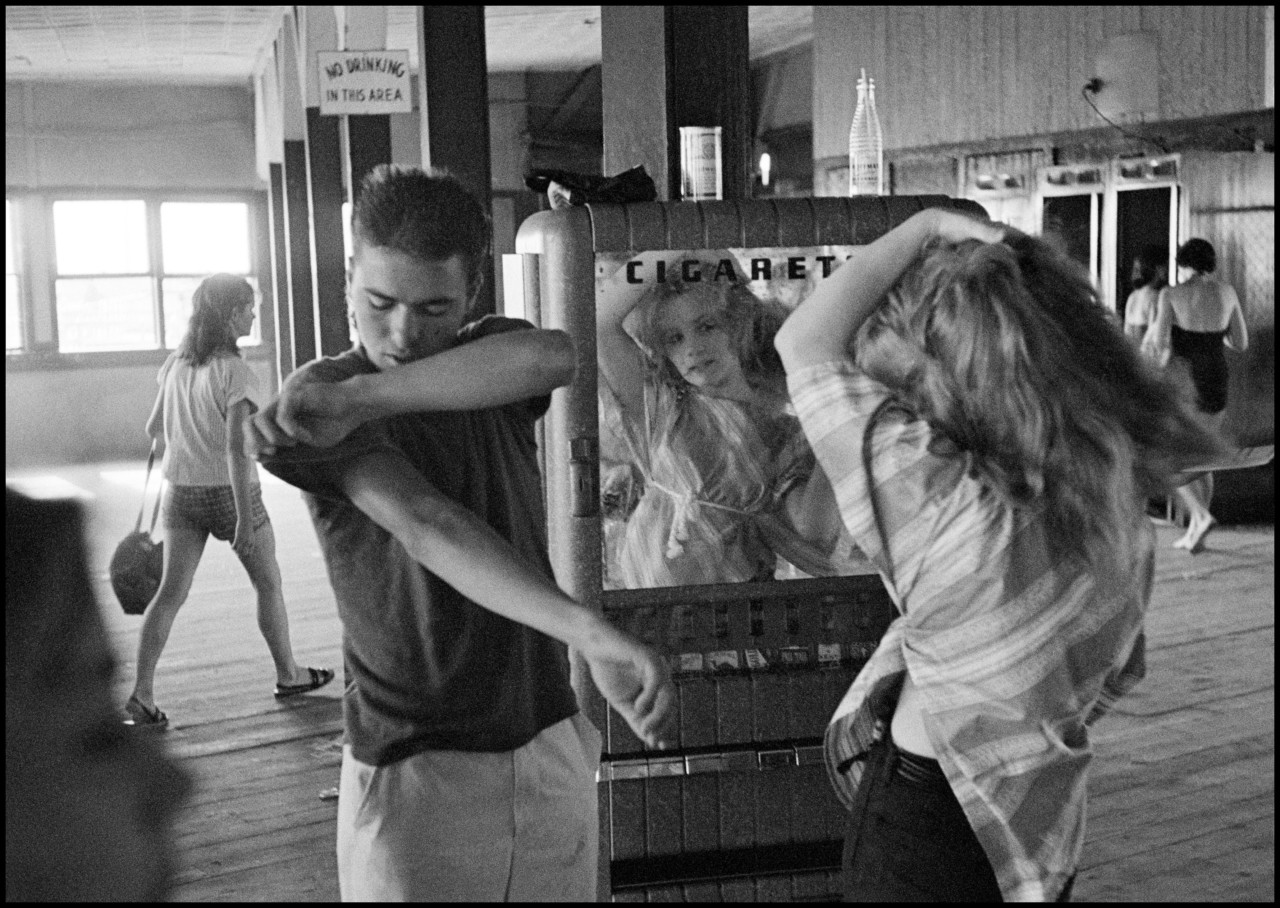

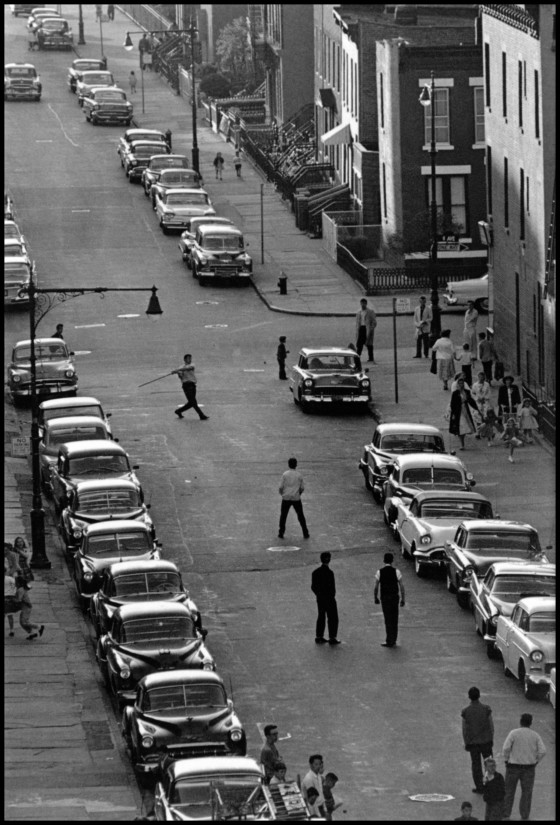

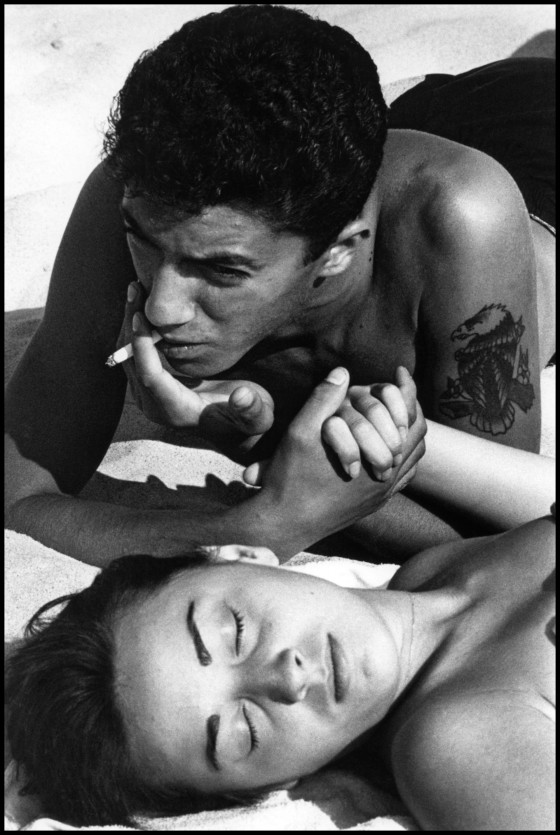

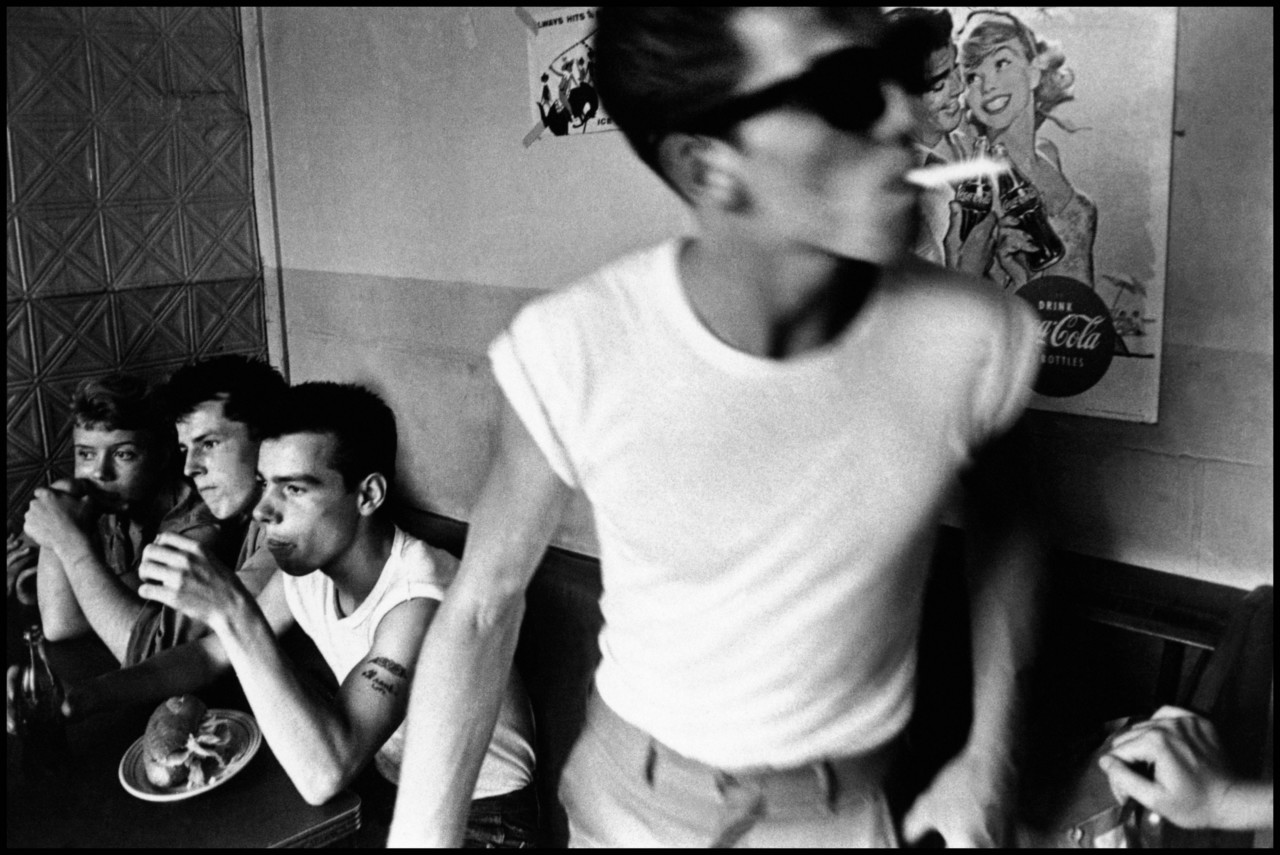

Preferring to follow his own vision without strings attached, Davidson refused a tempting offer from Life to become a staff photographer and in 1959, without an assignment, he started working upon his series, Brooklyn Gang. Even though the gang, who called themself The Jokers, had been in the news for instigating street fights, the series is not about violence or even gangs, but rather about what is means to be an isolated, aimless, abandoned teenager, poor and with few prospects. The photographer was filling a need: the kids felt invisible and were starved of attention. Though nine or ten years older than they were, Davidson identified with them – in an image where he is sitting under a tree with a few of the boys, it is hard to tell them apart. He shadowed them for a whole year, and in time they forgot about his presence.

"The series is not about violence or even gangs, but rather about what is means to be an isolated, aimless, abandoned teenager, poor and with few prospects"

- Carole Naggar

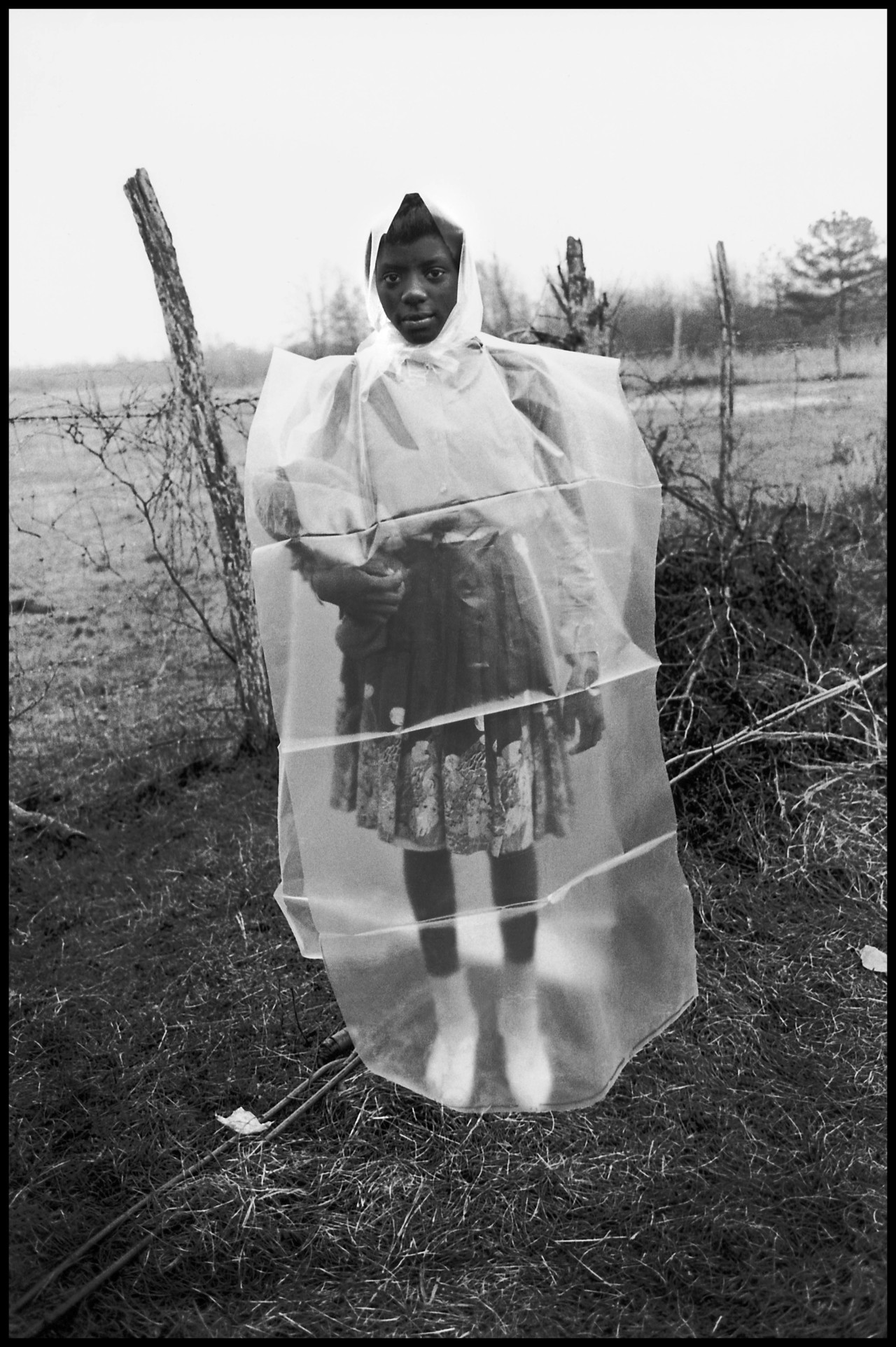

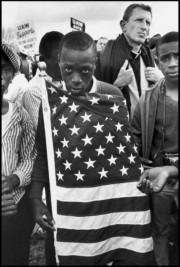

Though he never considered himself a political photographer, one of Davidson’s most remarkable series in this retrospective is the long-term work he made from 1961 to 1965 on the civil rights movement. He started at a time when the civil rights struggle was exploding into violence, after a racially mixed Freedom Riders bus was attacked on May 14, 1961, outside Anniston,Alabama, by angry whites. Volunteering for the Magnumassignment, Davidson got into a bus traveling from Montgomery, Alabama, to Jackson, Mississippi, with blacks, whites and the state troopers who accompanied them. As a Northerner, this trip was the first time Davidson would witness the extent of racial prejudice in the South, and he kept returning thereafter: documenting black life in the countryside and in small towns, in poor cabins and one-room schoolhouses.

"While he took part in almost every major march and demonstration of the era... his pictures are never overtly dramatic and rarely show violence directly"

- Carole Naggar

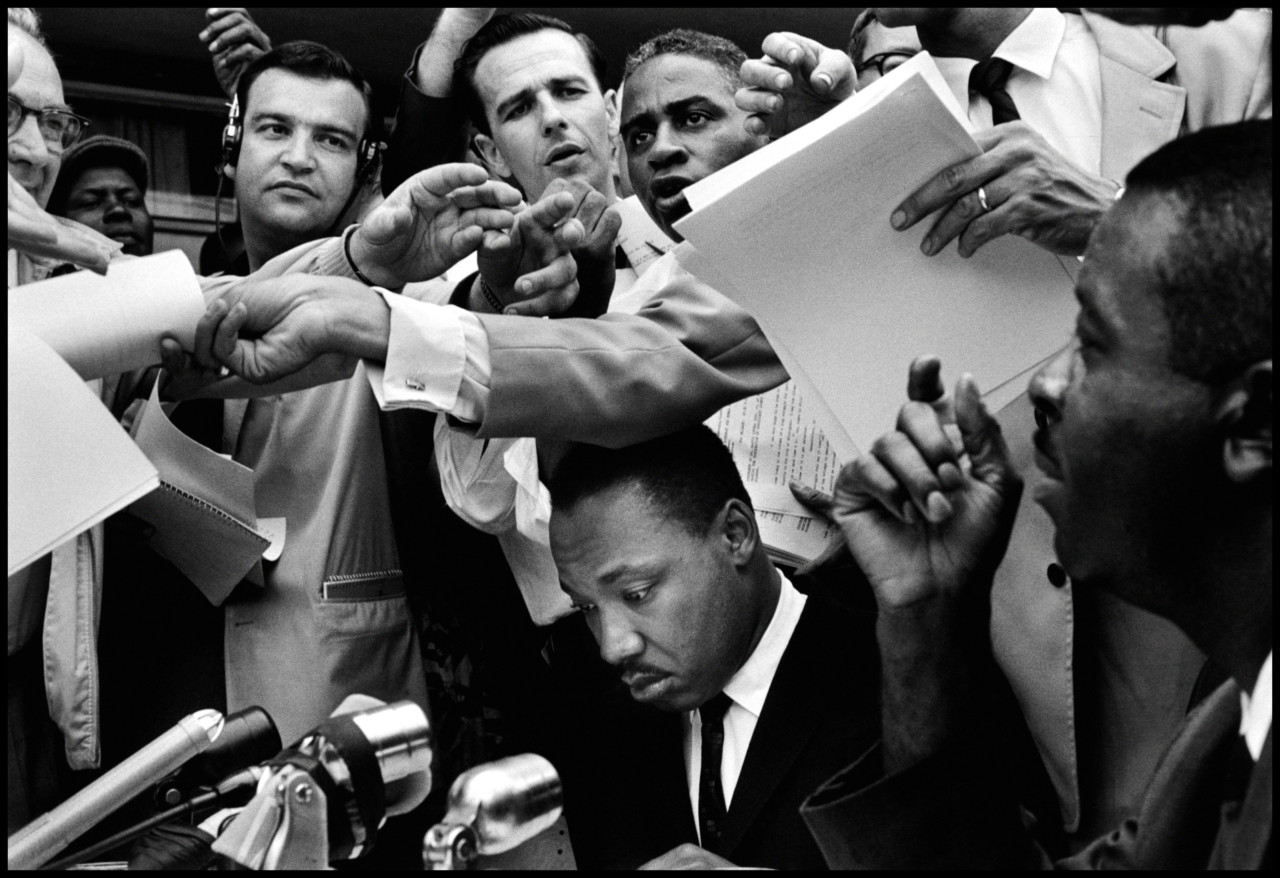

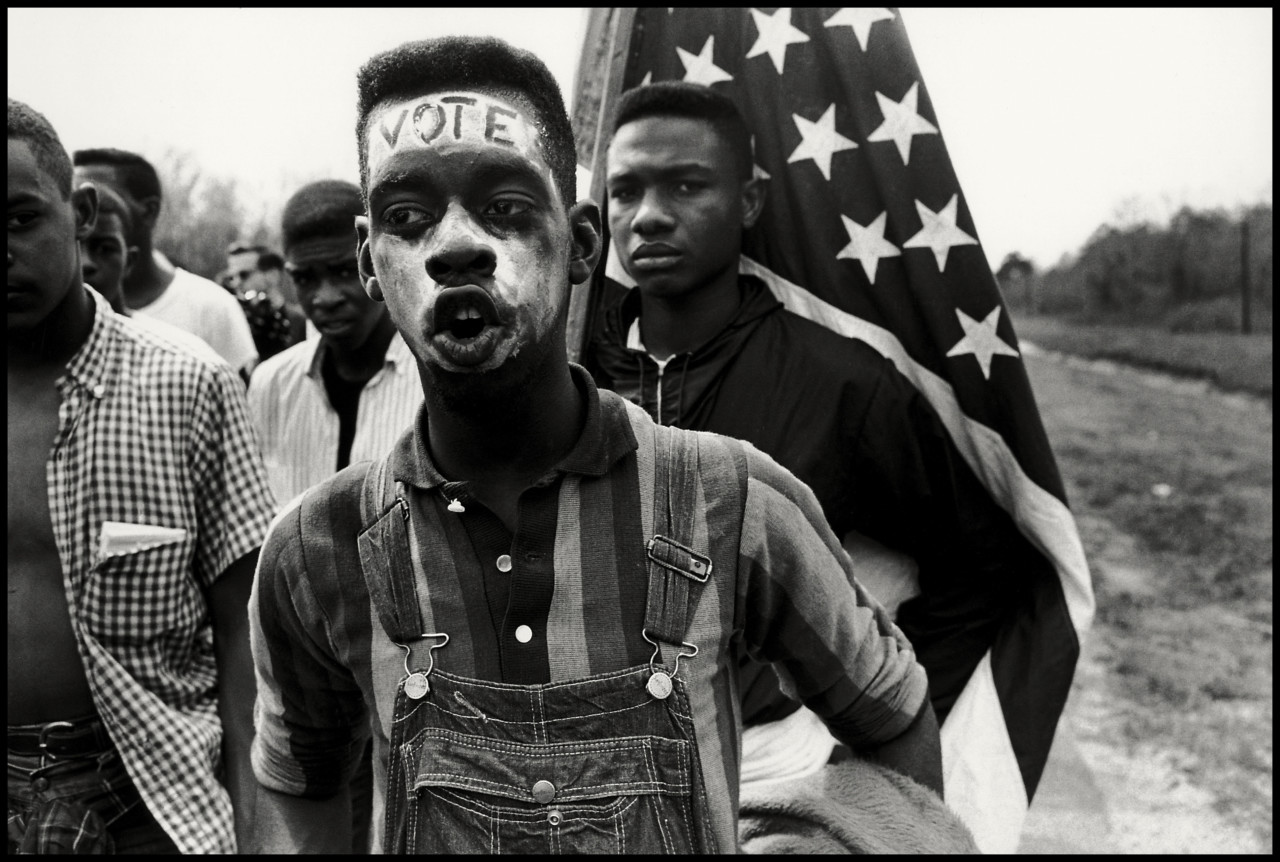

While he took part in almost every major march and demonstration of the era (including the Birmingham riots, the March on Washington, the Great Freedom March from Selma to Mongomery, the Mississippi Freedom March, and the Malcom X Rally in Harlem) often taking physical risks – for instance he barely escaped after he photographed a Klan meeting – his pictures are never overtly dramatic and rarely show violence directly. A strong and unconventional image is that of Martin Luther King at a 1963 press conference, crowded and overwhelmed by a group of journalists that loom over him. Another equally eloquent image, which became a symbol of the Civil Rights struggle, was taken during the 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery: a young black man, his face painted white with the word vote written on his forehead.

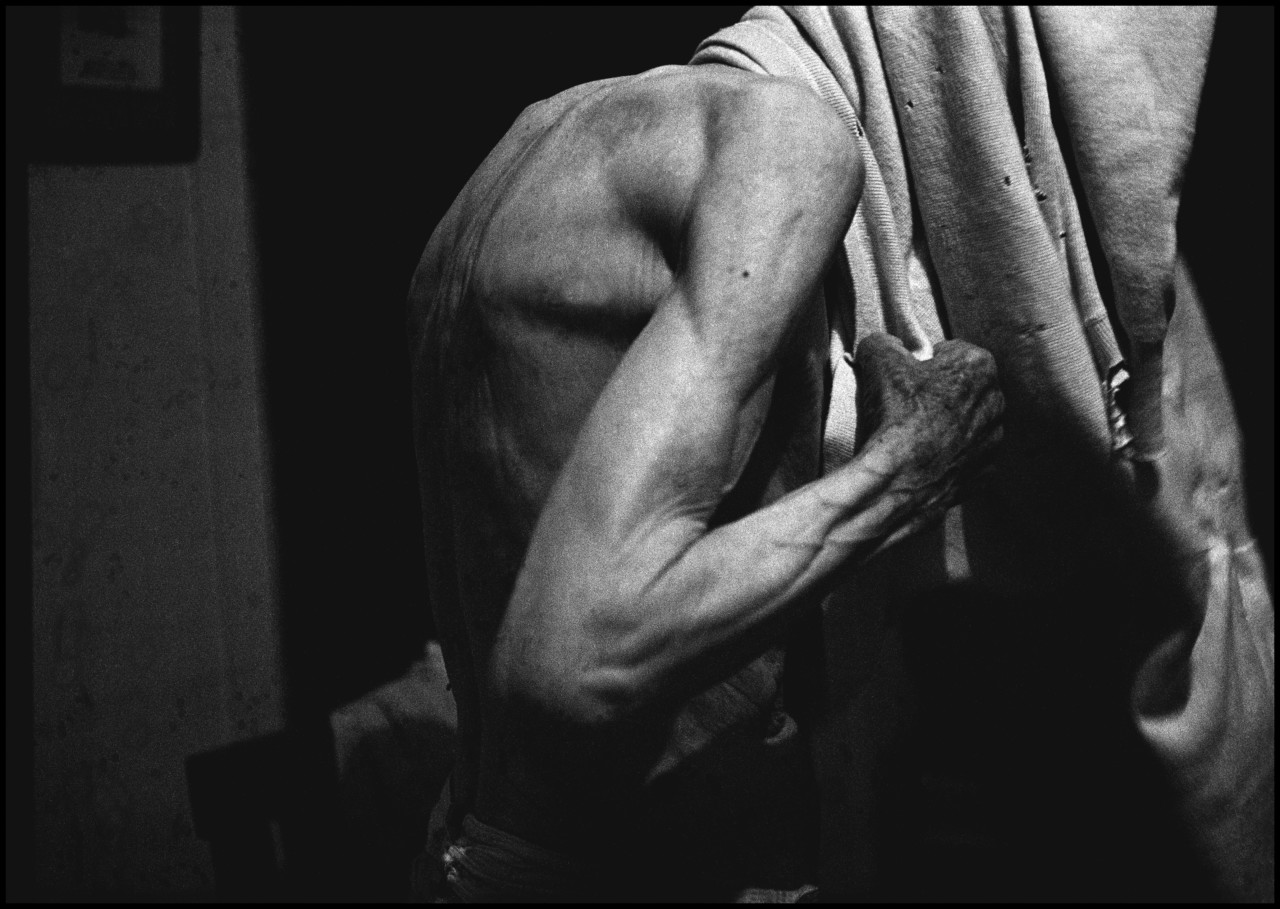

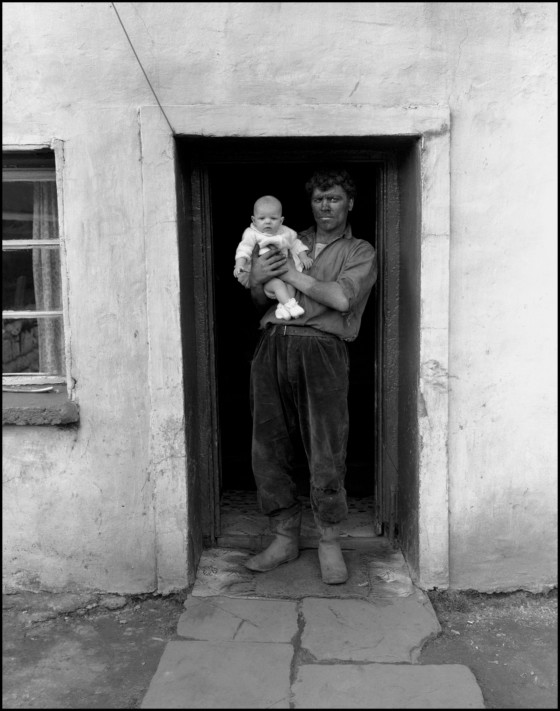

With his 1965 series on Wales, Davidson returned to a more intimate and poetic vision, portraying the miners returning from work, faces streaked with coal, but also more whimsical images: a statuesque white horse lying in a field, a girl alone dancing in a cemetery overgrown with wild grasses, or a boy pushing a stroller with a doll and a teddy bear along a desolate road : a line of laundry hanging in the background offers the only light in an otherwise bleak image.

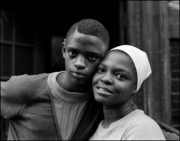

Davidson’s work in Harlem, New York, which became the book East 100th Street, went on for two years, starting in 1966. “What you call a ghetto, I call my home,” said one woman he met on what was then arguably one of the worst blocks in the city. Photographing with a slow and cumbersome 4 x 5 camera – a tool until then not used in documentary photography – Davidson was intent on stressing his seriousness of purpose, on being noticed and accepted by the people he photographed who, though living in tough circumstances, displayed dignity and a strong spirit and often welcomed him into their homes. He would then come back to give them prints.

East 100th Street was the first book comprised of documentary content to present itself as an art book, beautifully printed and with large margins around the pictures. The work brought Davidson in equal parts fame and controversy: while some critics loved the images, others saw them as too “arty” for their subject matter. But Davidson’s main intention was to show the city agencies and the mayor what was going on in terms of New York housing, and in time his pictures succeeded in helping to rebuild a community.

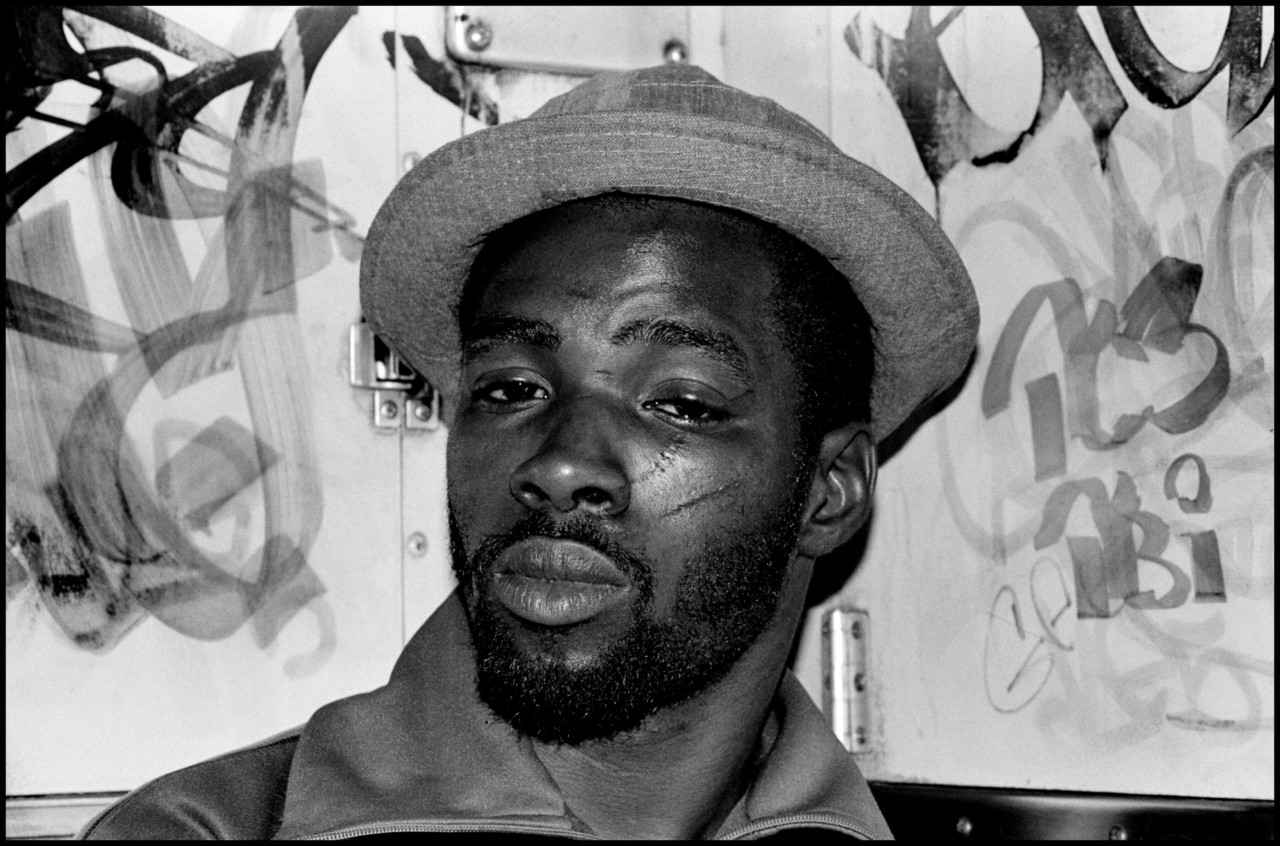

For his Subway series (1980) Davidson, traveling all over New York’s underground and working with a strobe light, juxtaposed the bodies and faces of the travelers against the background of ever-present graffiti like modern-day frescoes. Though a crowd surrounds them, the individuals seem lonely and oblivious to their surroundings. To get their permission Davidson showed them images he had already taken, pasted in a small, white wedding album he carried in his pocket. One of Davidson’s most striking portraits is that of a black man with a tilted hat and a scar on his cheek. As he returns the photographer’s gaze, he seems both wary and menacing.

Surprisingly, this photographer of human beings later turned his lens upon plants and trees, exploring nature within cities like Los Angeles and Paris, and in New York City’s Central Park. Landscape is people to me,” he told me. “To me a tree is as lovely as a bathing beauty.”

It is surely this sense of almost child-like curiosity and wonder that keeps Davidson, now 85, still interested and active. “I don’t know what I’ll do next, but it always has to come from inside, some sort of quest, a mystery, a magic that gets you into a world. The quest is as important as the outcome.”

You can get more information about the current leg of Bruce Davidson’s touring retrospective show here.