The Coast

Sohrab Hura discusses his new book, and the interplay of photography, moving image, and book-making in long-term projects

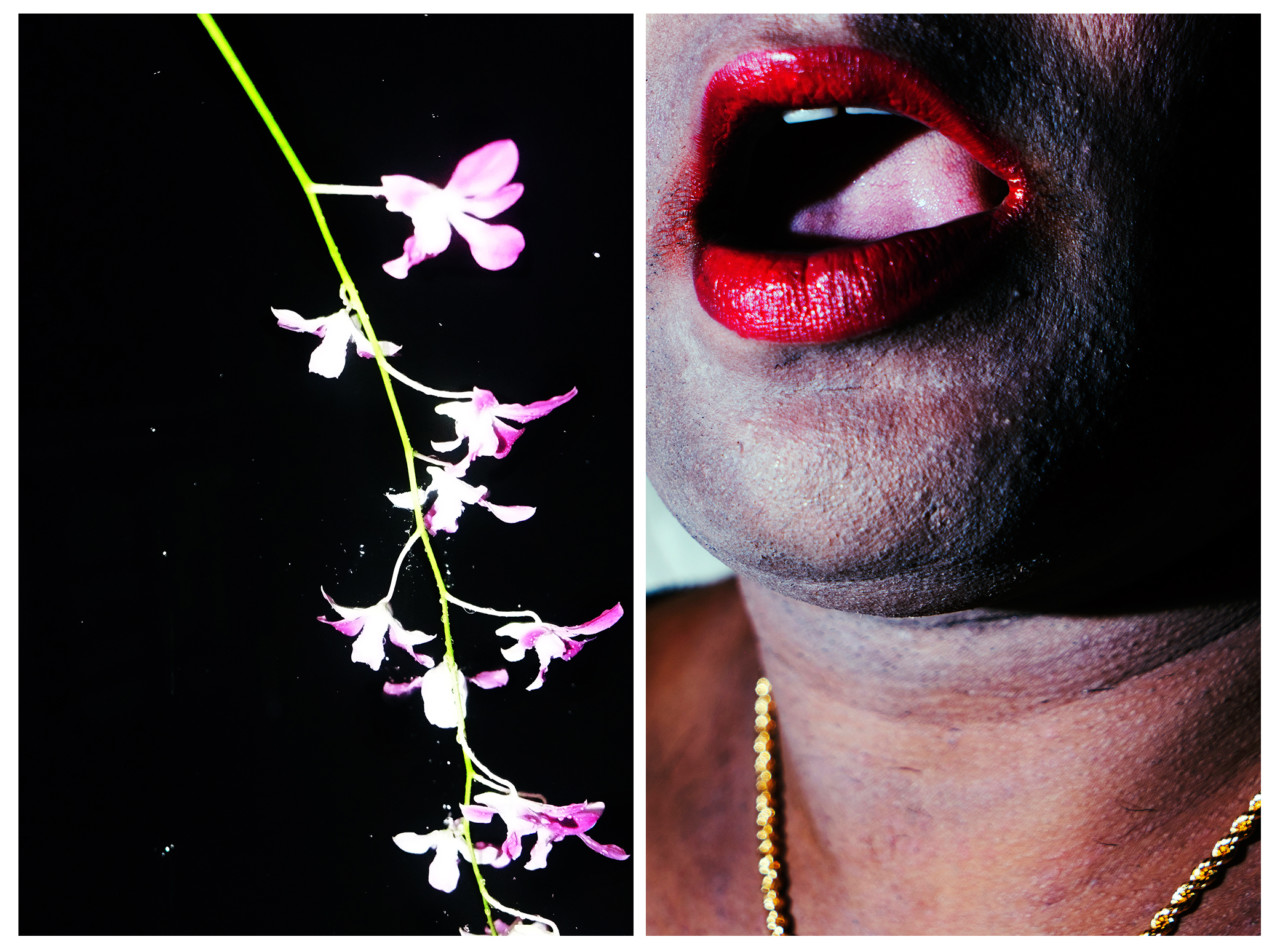

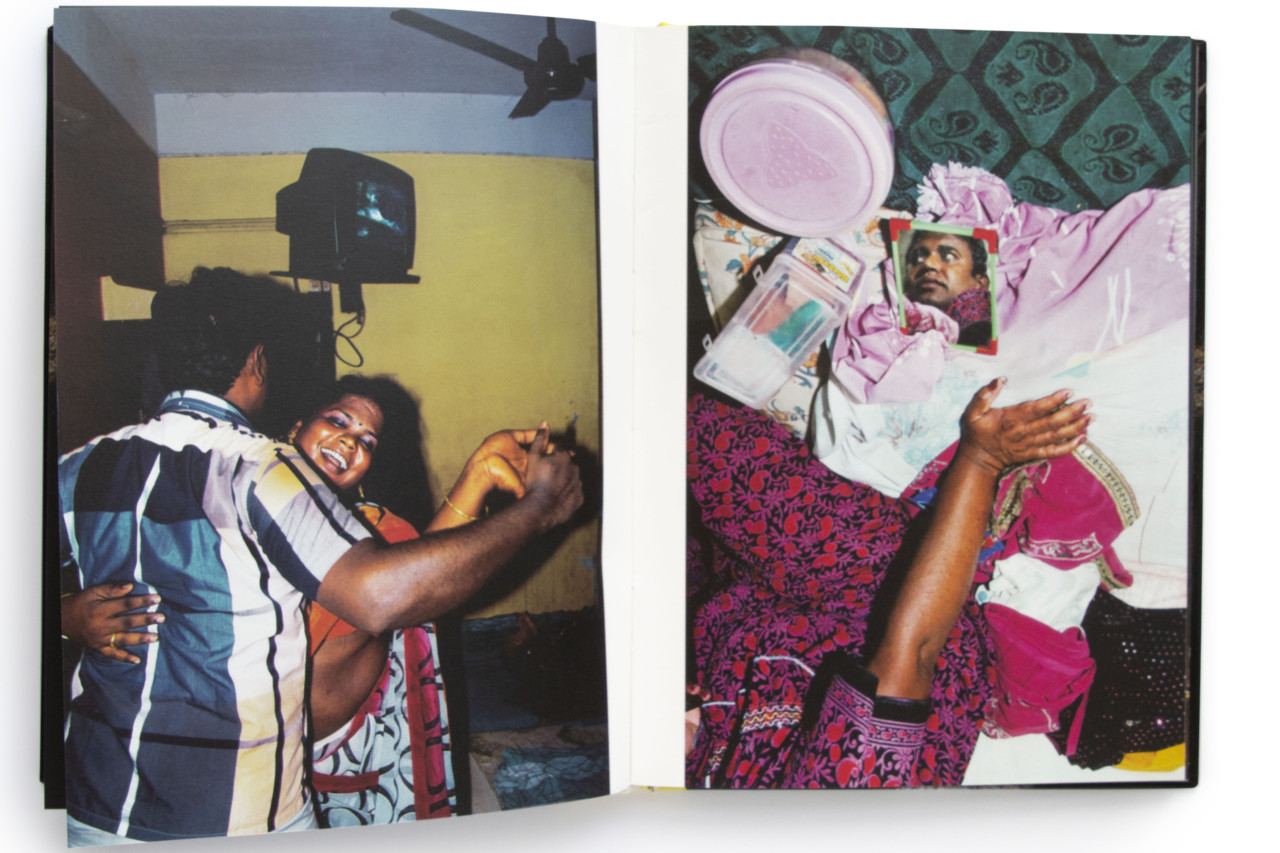

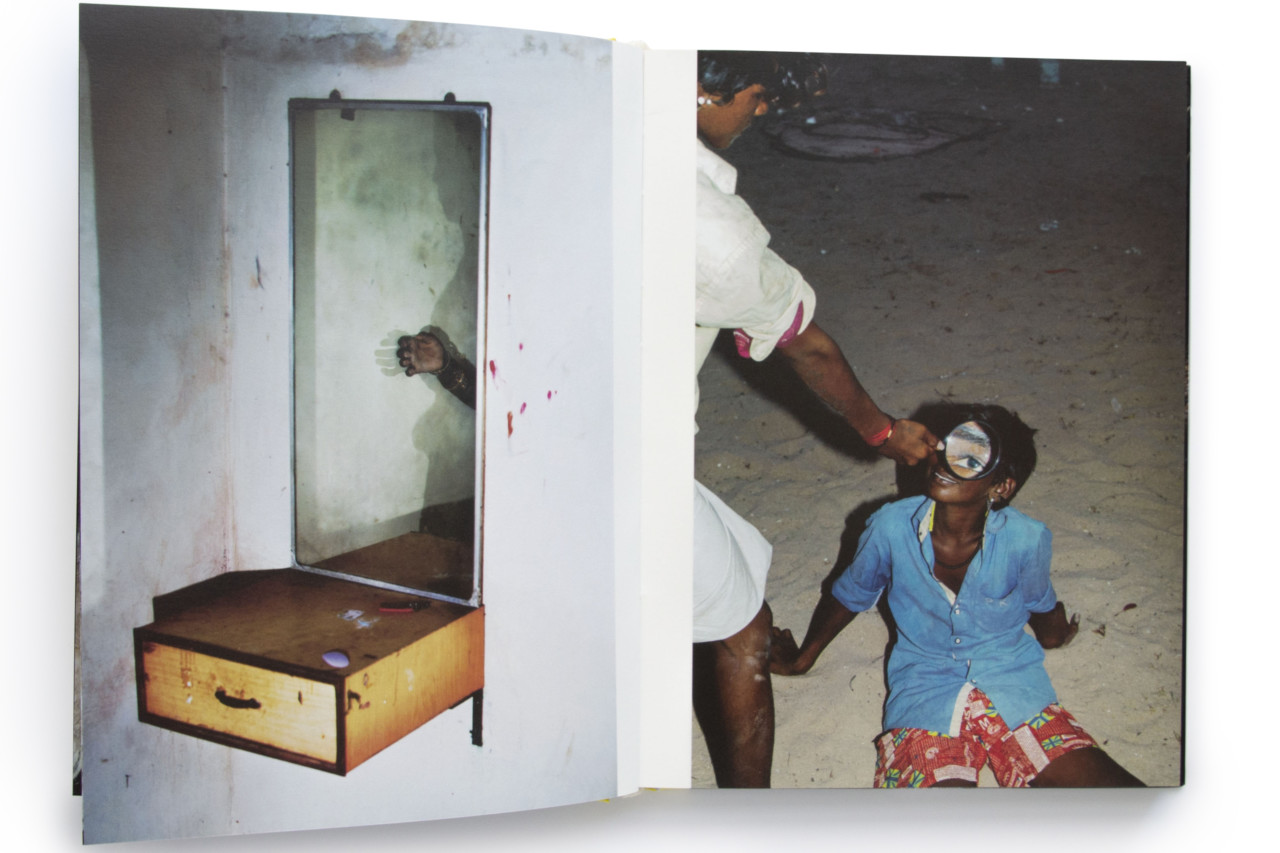

Magnum photographer Sohrab Hura’s new book The Coast is the latest iteration of his long-term project The Lost Head and the Bird, which explores the undercurrents of violence – religious, sexual, and caste related – in contemporary India through photos taken along the country’s coastline. While the project has previously been realized as a short film, which utilized at times brutal found-footage alongside Hura’s photographs – building toward a frantic crescendo, The Coast sees the photographer focus upon his own images and his slowly morphing text to convey these undercurrents. By stripping his images of contextual specifics, and by varying their pairings throughout the book’s pages, Hura blurs the lines between truth and fact – creating a book which he feels “some might imagine to be a fable-like tale, while others might recognize in it, reality.”

Here, the photographer discusses the book, the politics of violence, the interplay of text and image, and the importance of a plurality of formats in his practice. [Hura’s answers were given prior to the Indian Elections of May 2019]

Signed copies of The Coast are available now on the Magnum Shop.

How does your short story function within the book, and how has its function developed over the course of the project?

The short story repeats itself throughout the book in 12 different iterations; each version different from the preceding story in only a few words. From the 1st to the 12th iteration, these changes create a shift in empathy. For example, in its original format the story has the obsessive lover, the fortune-teller and the idiot photographer (me) all partaking in the violence in the main character Madhu’s life, however by the 12thiteration all these characters have been absolved of their roles in any wrong doing and in fact the blame for Madhu’s circumstances have been subtly shifted back on to her. Finally, it is she who is responsible for her own miseries.

In the work as a whole I’m not so interested in the fact or fiction of things, I mean I’m playing with that line for sure and they do determine the starting points of different realities but I’m more interested in the workings of the larger system where meaning is assigned or taken away by making the smallest of changes in context.

The elections are on in India as I write this and this specific method of the manipulation of context, to assign and retract realities, is in full swing here – especially with the current political disposition that is constantly playing with context and attempting to escape culpability by distracting away from questions raised to hold it accountable.

We might have a set of facts, but what we mould around these facts, and how, is what ends up constructing these realities. I’ve played with the short story in a way that is similar to playing a game of Chinese Whispers where the message is distorted in each retelling. It’s just that this is no longer a game, but the world that we are living in. I’m only trying to dissect the workings of this world through this breaking down of my story in its many forms and the alternating juxtapositions of images within the book. Some images might seem brutal in one context or might turn silly or funny when juxtaposed with another. But there is a narrative engine or story line that does continue to go forward in a haphazard non-linear way.

"There is a sort of new language of photography coming into existence because of the looseness of social media"

- Sohrab Hura

Did the process of making your film on the same subject and using the same body of photographs alongside found imagery effect or alter your approach to designing the book? Do you think that process changed how you view the work fundamentally?

For me the book and the film are completely different works even though they are bound together. There is no found imagery in the book. The purpose the found material in the film was to lead the audience into the real world out there, which is far more immediate than any photos that I could make. By assimilating all that material in the film’s end, I was just trying to amplify something that we might already recognize, but which we might deny.

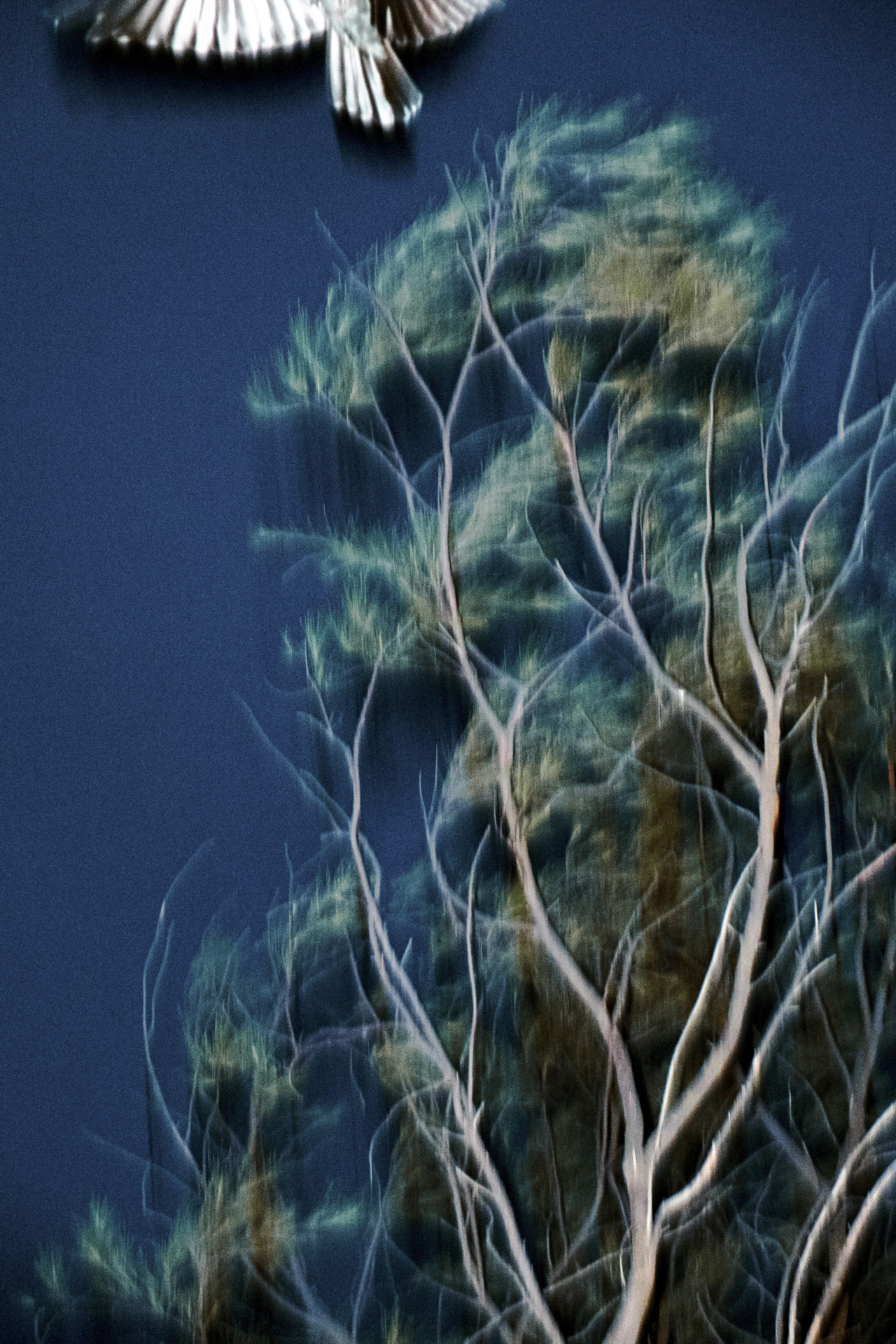

The book, on the other hand, alludes to undercurrents rather than dragging the audience to a precise spot. While the beginnings of both the book and the film overlap, they diverge into different points of release: The film explodes with found material at its end while the book gently crosses over into the sea, to where this edge between land and water becomes a tipping point.

"If I were to merely reproduce the film in a book, it would strait jacket the work into a single meaning but for me the beauty of photography lies in its malleability and multiplicity of existences and meanings"

- Sohrab Hura

These images in the sea have been made over the years on a specific beach in Tamil Nadu, where every year – during a religious festival – people masquerade as different characters depending on what they have prayed for. They get into a trancelike frenzy in worship and are they are finally carried to the sea to wash themselves of their masquerade, much like cleansing themselves of their sins. In fact the image on the book’s cover is part of that masquerade, before being washed off.

In a way we are all wearing masks. I looked at how the current climate of violence is defined by those masks that dominate. Coincidently, The Modi wave that brought a change in the political and social regime five years ago also manifested itself in a sea of masks with the face of the current prime minister on them that were swirling around us. This stepping into the sea is a sort of a new beginning for the people, a sort of a shedding of that mask. In its metaphors, the book ends with a little more relief – one could even say hope – compared to the film.

There is also this indirect connection between the last section of the film – with all that found footage and the photography within the book (and of course in the film). There is a sort of new language of photography coming into existence because of the looseness of social media. It’s weird, it’s surprising, it’s ugly, it’s beautiful, it’s voyeuristic, it’s narcissistic, it’s ordinary, it’s precise, it’s misleading, it’s a lot of contradictions put together. Yet it somehow makes sense to me. That influenced a lot of the photography that is there, in the book.

What is it that the photobook offers you as a photographer? It seems to be a vehicle you return to often to present your work in its ultimate form, even if – as discussed – you work in film and other formats?

I do not think that the book is necessarily the ultimate form for me in general, nor do I think that every work must live as a book. In fact, I do not want to consider any hierarchy amongst different forms. That would be limiting, I think. There are some works of mine that have only lived as video works, for which a book doesn’t make sense. There are other works where prints on a wall can help create the most efficient pauses. There are also works that I feel run risk of feeling a bit too precious as prints, or as a book, which I’d rather just let exist online. Intent helps me find the form, but if a work has a large enough range of tones then for sure I’ll experiment with as many forms as possible.

In the case of The Coast, the personality of the book needed to be quite different from that of the film, The Lost Head & The Bird. It needed to be gentler and slower to be able bring to the surface all that might have been ignored by the film. The film has an urgency that the book gives up on. If I were to merely reproduce the film in a book, it would straitjacket the work into a single meaning, but for me the beauty of photography lies in its malleability and multiplicity of existences and meanings.

I hope that one day my working history might be experienced like a tree; a trunk branching out into arms of different works. The smaller offshoots holding the leaves might be the different forms: books, films or whatever else I do with the images belonging to the same work. Each offshoot, no matter how different from the neighboring ones, is connected to them by a larger branch and each branch of a different body of images is connected to the other branches by a single trunk. I hope the roots will be deep. What I write here reads very embarrassingly to me, but I can’t find any other way to articulate this interconnectedness between different works of mine and their corresponding forms.

"With this book I had to start from scratch"

- Sohrab Hura

Did your playing with sequencing and diptychs for the film feed directly into the editing or sequencing of images in the book?

The sequencing of the book is similar to the film, but only in parts. There was initially a temptation to build completely on the original sequence of the film to make the book. However, some of the juxtapositions didn’t make any sense when I looked at them in a book’s pages. With the accelerating pace of the film these image juxtapositions start to taper out and cease to matter beyond a point – so I could get away with many portions of the sequences especially towards the end when the pace is fast. But the reading of a book is more or less constant [in pace] and so I think the sequencing needs to also be way more precise.

With this book I had to start from scratch and remind myself that I needed to also bring in that tipping point between land and sea which I mentioned earlier. There needed to be a build-up towards the sea rather than a tapering out as occurred in the film. That would also make sure that title – The Coast – was more fleshed out in its purpose, otherwise this sort of sequencing that I’m attempting might have been reduced to a being just a gimmick. So yeah, it’s Same Same But Different.