Martin Parr in Wales

A new exhibition and book charts the photographer's decades of work in the country

As part of its 2019 photography season, the National Museum Wales is currently exhibiting a selection of images made in Wales over the last four and a half decades by Martin Parr. The photographer was drawn to the country in part by his ongoing fascination with documenting the people of the British Isles at leisure, but also covered Wales’ working men’s clubs, agricultural and mining industries, and of course it’s food. The exhibition in Cardiff will show many works never previously exhibited. The show will run until 4 May, 2020. More information can be found here.

The accompanying book, Martin Parr in Wales, is published by National Museum Wales and is available now on the Martin Parr Foundation’s shop.

Below, we reproduce the book’s introductory essay by Welsh poet Owen Sheers, alognside a selection of Parr’s images from Wales.

This exhibition is not about Wales. What I mean by this, is that the images that make up its whole were not created in an attempt to capture the personality of the nation. They are not a concerted excavation of a specific communal identity. Martin Parr confirmed this for me in conversation recently when he described them as ‘photographs I took over the years on my way to Tenby and back.’ The geographical scope of the settings and landscapes suggests this isn’t quite the case – as you walk through the exhibition or turn these pages you’ll also be taken into mid-Wales and into the north – but the sentiment behind his statement rings true. These images are not the result of a photographer going in search of something, but rather a document of what he saw as he passed through Wales on another journey entirely.

That journey, of course, is Martin’s own; the gradual deepening and tuning of his aesthetic tendencies and instincts, mapped here over the decades across the beaches, shows, valleys and peoples of Wales. Looking through the images for this introduction it’s difficult not to feel that the character more often explored in their captured moments is that of the observer than the observed; Wales as a mirror, reflecting the inscape of Martin Parr more than the inscape of the nation.

This shouldn’t surprise us. The consistency and signature of Martin’s gaze is one of his strengths as a photographer. There are, I would argue, only a handful in the 20th and 21st century whose work can be so confidently and instantly recognised as their own. I’ve even heard his aesthetic become an adjective, when someone looking over a summer beach or a crowd spots a particular scene and says to the person at their side – ‘Look at that. It’s very Martin Parr isn’t it?’

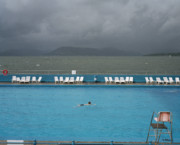

So what are the qualities of Martin’s gaze that can illicit such a response, such an instant recall of his images to the moment? At the heart there is nearly always the communal patterns of leisure, and more specifically a study of the ephemeral unguarded moment within the context of holiday, hobby, time off or event. This is what seems to draw his eye again and again – how do we behave, move, celebrate and look when freed from the constraints of work and schedule into the looser, but still often socially prescriptive, rhythms of organised relaxation? This is why the bank holiday weekend, the new year’s eve party, the beach, the beauty spot, the municipal pool or park have always been such fertile territory for Martin. These are the places that draw the holidaying herd, where he can observe the individual and the crowd at once; where he can be apart yet close enough to record the joys and pathos of what we do with time and each other when both, briefly, are offered to us as our own.

"Parr is perhaps the laureate of the turned head, the back of the neck, the side profile, the silhouette"

-

Although expressive, these moments are rarely given expression. Parr is perhaps the laureate of the turned head, the back of the neck, the side profile, the silhouette. Such a perspective lends further weight to the sense of a singular vision that haunts so many of his images – the camera as omniscient observer, the eye that looks at the lookers, the visual energy of its lens charged not with the intimacy of experience but rather the composition of observation. The unchoreographed reciprocal gaze is a rare occurrence in a Martin Parr photograph. More commonly the register of the image is one of the subject having been caught (or perhaps, more accurately, taken) while unaware of the action. More recently this tone of surreptitious observation has been strengthened by Martin’s use of a telephoto lens. Where once expressions were obscured by looking away, now they are obscured by distance. The camera retreats, and in doing so the communal pattern dominates – a line of people queuing for ice cream, day trippers scattered across a shore, mourners waiting for a boat. With that retreat the interpretive space also narrows.

"The liminal, choral, ever-changing and ever-constant British beach. As the quintessential destinations of leisure it’s clear why tourist beaches and coastal towns have always held such a fascination for Martin"

-

The unspoken dialogues or monologues of his closer work are rich with possible story. With distance those stories melt into the broader scope of the tableaux, the group ‘voice’ eclipsing the individual.

All three of the images just mentioned take place in that most Parresque of landscapes – the liminal, choral, ever-changing and ever-constant British beach. As the quintessential destinations of leisure it’s clear why tourist beaches and coastal towns have always held such a fascination for Martin. But they are also rich in another attribute that seems to pervade the landscapes of his work, in that through his lens they often appear somehow borrowed, only briefly occupied by the human. The same can be said here of his hilltops, where the added juxtaposition of the suburban with the natural accentuates this quality; and even of some of his urban scenes, strangely evacuated bar the odd survivor left in the frame, looking lost in that gap between the civic aspiration and the reality of its experience.

"Somehow, however, Martin still manages to sustain the effect of the outsider on the inside, a still point at the eye of the human storm"

-

Move indoors, however, and the human suddenly seems more at home. This, in the world of Parr, appears to be our more natural habitat. The miner’s shower, the working men’s club, the practicing choir, the wedding. Faces come into view and focus. The pictures come to life, the group dynamic energising the frame. Somehow, however, Martin still manages to sustain the effect of the outsider on the inside, a still point at the eye of the human storm. His sense of humour has a significant part to play in this positioning; a curious vein of gentle ridicule and love which runs throughout his work and which for me finds its most perfect utterance here in that suspended butcher’s hand in Haverfordwest, disembodied and ‘hung’ alongside his wares. Not that it’s a humour that always requires people as its ingredient, as evidenced in Martin’s mischievous interpretation of a brief to photograph ‘Real Food.’

Turning his lens away from the wealth of Wales’s fresh produce, Martin’s focus, instead, is on the ‘real food’ of the everyday, elevating the ordinary through proximity – the cakes, baked beans, faggots and peas and just-out-of-date Jammy Dodgers of market day. Representative of Welsh cuisine? Of course not. But touching on that tension between the ‘real’ and the ‘processed’ that is so alive across our 20th and 21st century lives? Absolutely. Which, in a way, brings us back to where I began. There is nothing exclusively Welsh about those food images, but there is something familiar. The same is true of many of the exterior scenes in these pages. Taken in Wales, but not exclusively Welsh. Where ideas of nationhood or geographically specific culture do emerge they are also familiar, but in another way. Daffodils, agricultural shows, black-faced miners, working men’s clubs. There is an audacity at work here; a confidence in his vision that means he isn’t afraid of the cliché, the seen before. But then, as he isn’t attempting to capture a national essence, that somehow seems ok. Here, you feel, is a photographer not looking for the different, the unique, but rather the known; the moments and qualities we share as people, not nations.

"What he has done, is to use Wales as his canvas, his backdrop for a longer, more personal ongoing search comprised of questions about who we are as modern humans moving within the patterns of our lives"

-

It’s an approach that was confirmed by Martin when we spoke. ‘I’ve photographed in Wales, England, Scotland,’ he told me, ‘and they all have their minor differences, but in the end I see them all just as parts of the UK.’ Such a statement might seem culturally short-sighted, especially for someone whose vocation is looking. But it is also consistent with the nature of Martin’s vision. He has not gone looking for Wales in these images. He has made no attempt to visualise its unique linguistic character, or to capture its natural beauty, its grinding poverty, its split and conflicted personality as an ancient yet new nation, its recent journey towards and through devolution. None of this. What he has done, is to use Wales as his canvas, his backdrop for a longer, more personal ongoing search comprised of questions about who we are as modern humans moving within the patterns of our lives, our societies, our landscapes. In doing so, while often not seeing our country, he has graced us with becoming a part of another – the country of Martin Parr, with all its characteristics of humour, pathos, community and humanity. And for that, Martin, we say diolch.