The Beatles Through the Magnum Archive

To mark the 50th anniversary of the release of Abbey Road - the last record the band made together - writer Jeremy Allen looks at the archive on the Fab Four

Who hasn’t idly wondered what it was like to be a Mop Top at the height of Beatlemania? John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr were asked that question countless times over the years, usually answering with a roguish riposte (“what’s it like not being one?”). But what of the people who snapped them at the height of their fame? On the 50th anniversary of the release of Abbey Road, the recollections of the photographers who got up close and personal with the Fab Four during their time as the world’s biggest band offer some intriguing insights.

Magnum photographer Philip Jones-Griffiths captured the Beatles backstage at the Liverpool Empire when they were just on the cusp of becoming household names in 1963. While the photojournalist said little about his encounter with the Fab Four on record when he was alive, his photographs – and especially the one of Ringo signing autographs in his underpants – are very revealing. The Welshman documented working class life in the 50s and 60s in his hometown of Rhuddlan, Denbighshire, and in Liverpool. Speaking in 2008 ahead of the publication of his photobook Recollections, Jones-Griffiths said “[Liverpool] was where I went to expand my horizons, experience the world outside my village. It provided a mix of enlightenment and education and an early experience of multiculturalism. The bustling seaport city became my favourite!”

"The highlight was the reading of letters from female fans that shocked the group"

- Phillip Jones Griffiths

Jones-Griffiths would go on to document war in Vietnam and change American perceptions of the conflict along the way, with his uncompromising pictures which Henri Cartier-Bresson likened to the war etchings of Goya. By contrast, his meeting with the Beatles was a lighthearted affair. “I spent most of the time in their dressing room getting to know them,” he later recalled. “The highlight was the reading of letters from female fans that shocked the group. ‘How do they even know about this stuff!’ was one remark.”

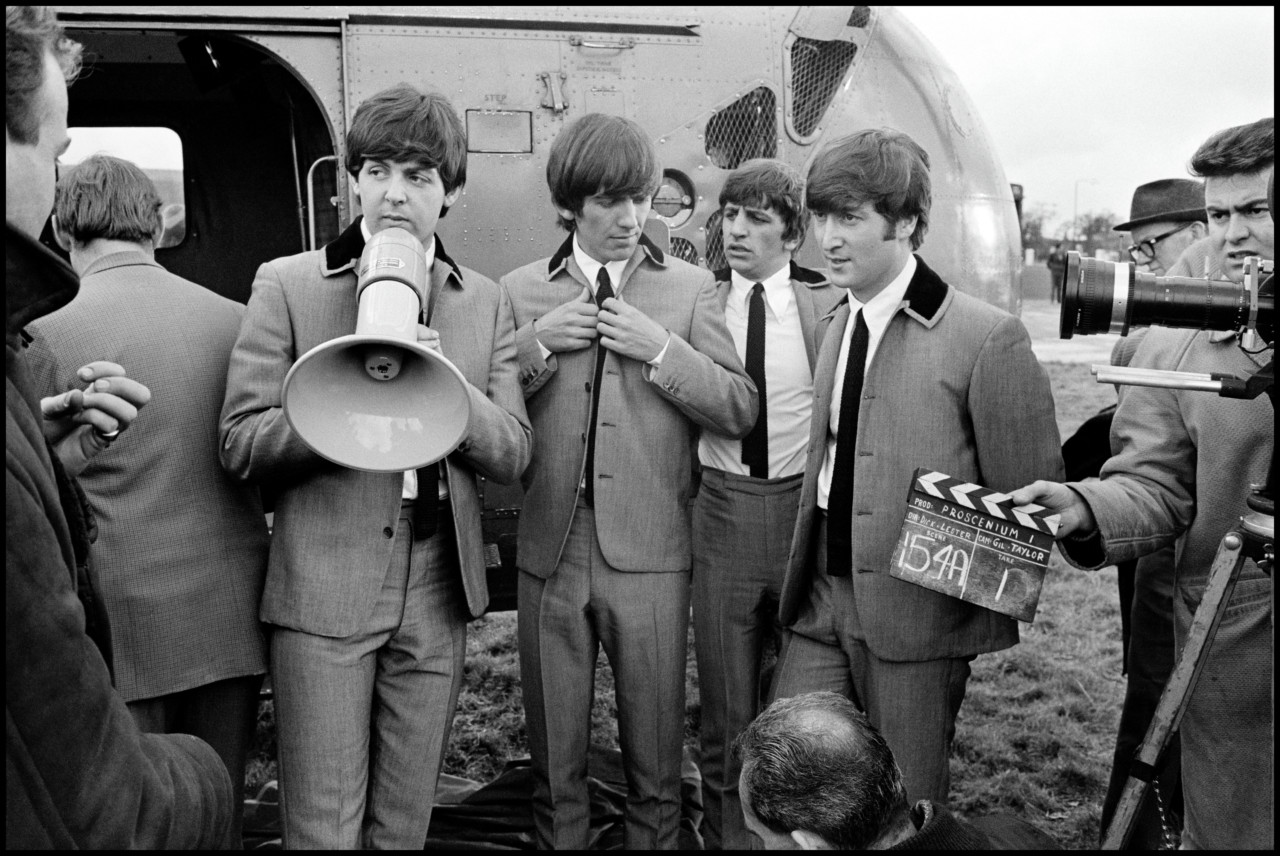

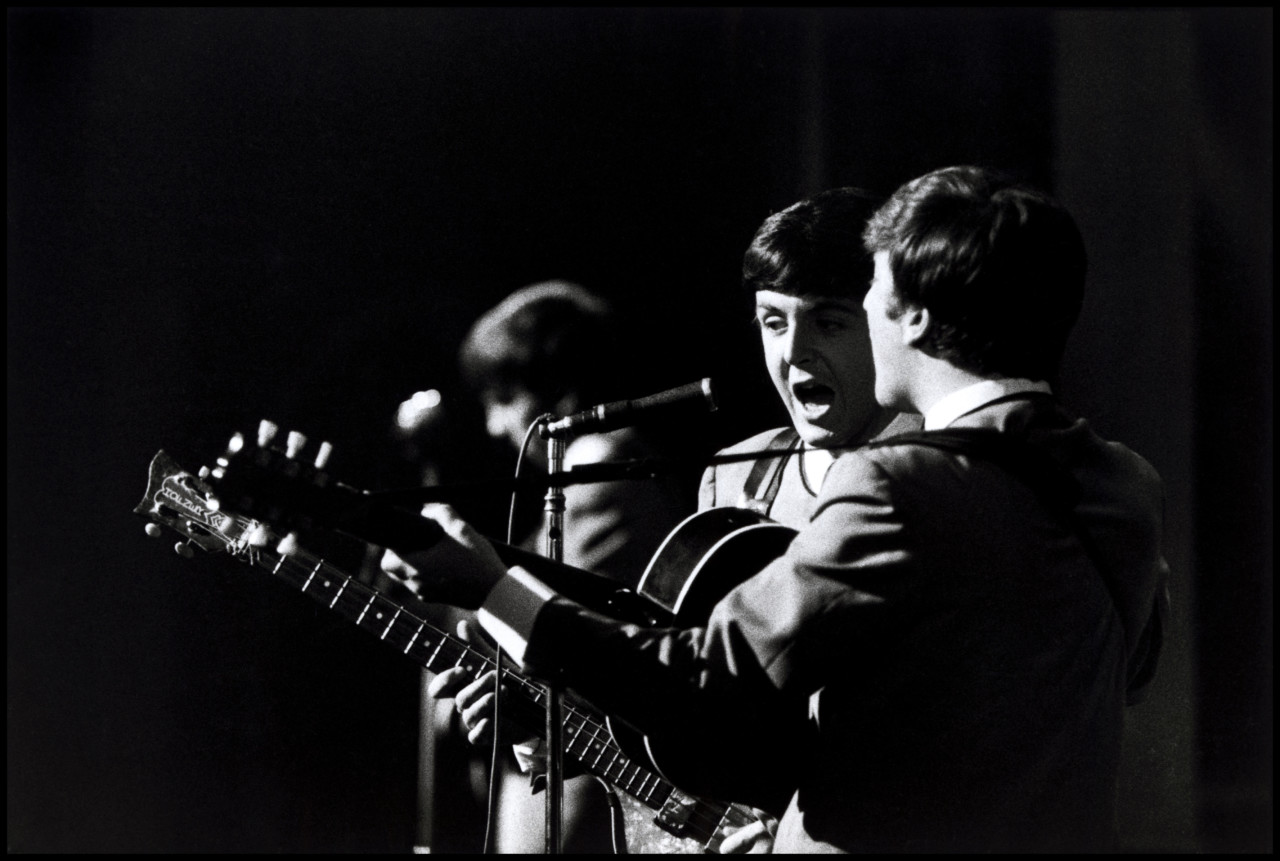

The Beatles that Jones-Griffiths encountered would have been the tight knit four-piece who’d not long ago honed their act in Hamburg, yet when another Magnum photographer, David Hurn, met the band a year later in 1964, world domination was in full swing. Having worked on Peter Sellers’ The Running, Jumping & Standing Still Film with director Richard Lester in 1959, Hurn had been invited to shoot on set during the making of A Hard Day’s Night. “My agreement with Dick Lester was that I wasn’t going to be like the normal stills person, even though I was there quite a lot,” he says on the phone from his home in Wales. “I was more interested in the relationship between the fans and the band, so most of the pictures I have are of them reacting to the fans in some way.”

"The Beatles couldn’t go anywhere. A couple of times they were in my car and the police would have to just wave us through a red light because they knew if the car stopped it’d be totally mobbed"

- David Hurn

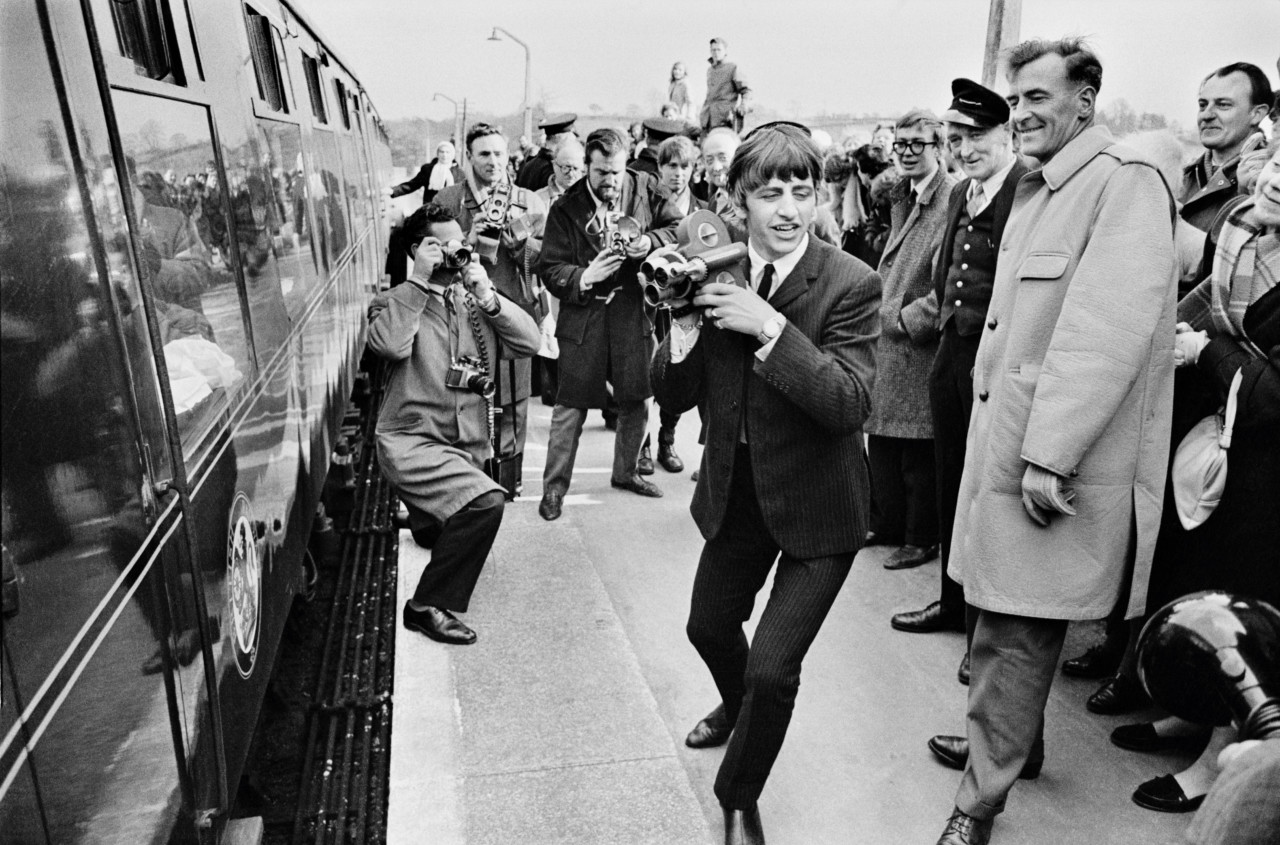

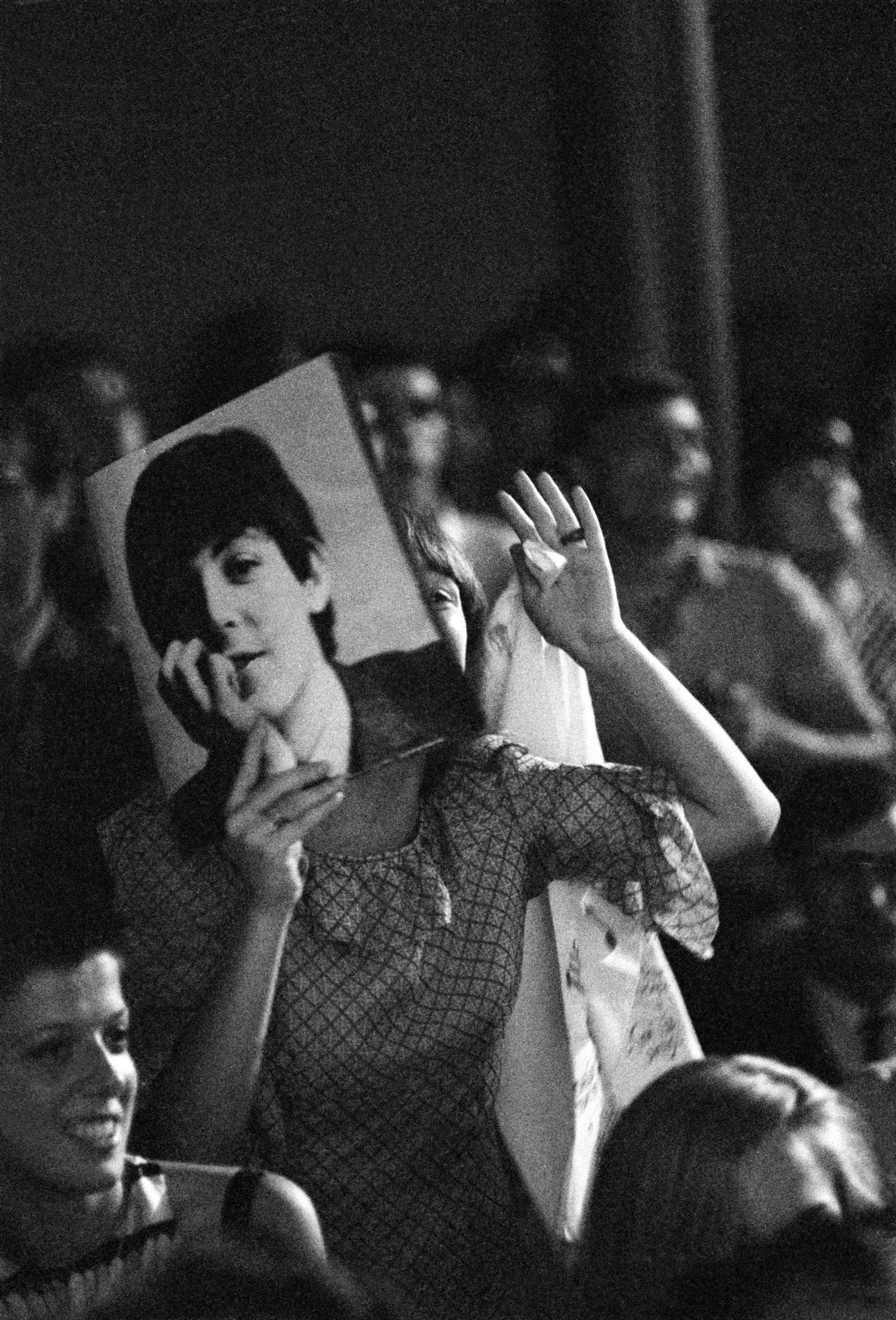

Shooting got underway at the beginning of March 1964 and wrapped up by the end of April. Halfway through filming, Beatlemania was at its apogee as the band simultaneously occupied Billboard’s top five single places, a feat that has never been repeated. As a pictorial study of fandom, Hurn’s timing couldn’t have been any better. “They’re the biggest band that has ever been and I suspect they had the most ludicrously fanatical fans ever too,” he says. “The Beatles couldn’t go anywhere. A couple of times they were in my car and the police would have to just wave us through a red light because they knew if the car stopped it’d be totally mobbed. The effect it has on four young guys must have been enormous, and it must raise all sorts of things that none of us know about.”

Hurn got to know the band well in their peculiar incarceration. Sequestered away from the hordes of screaming fans held back by a chain of bobbies, it forced them to turn to mundane pursuits to alleviate the boredom. “One of the things we used to do was play Monopoly together,” says Hern, laughing. “One of my regrets is that there are no pictures of us playing, and the reason for that is that I was so competitive I didn’t think to get up and take a photograph!”

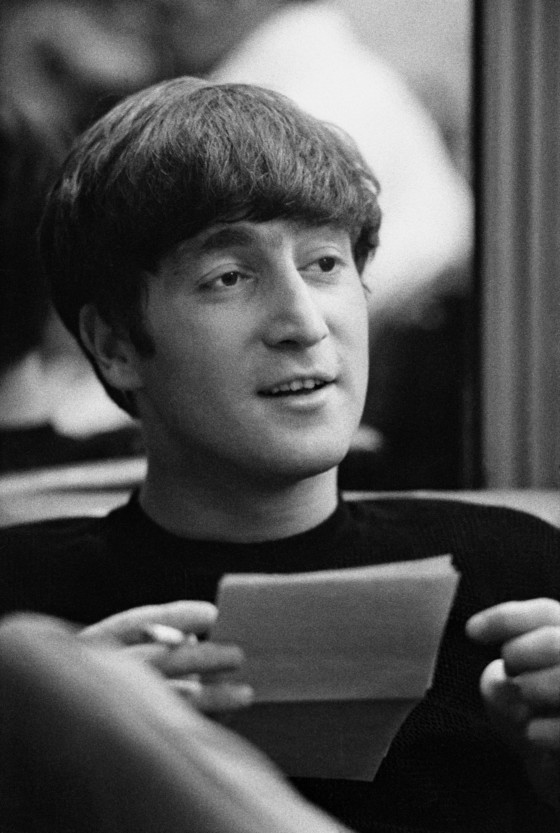

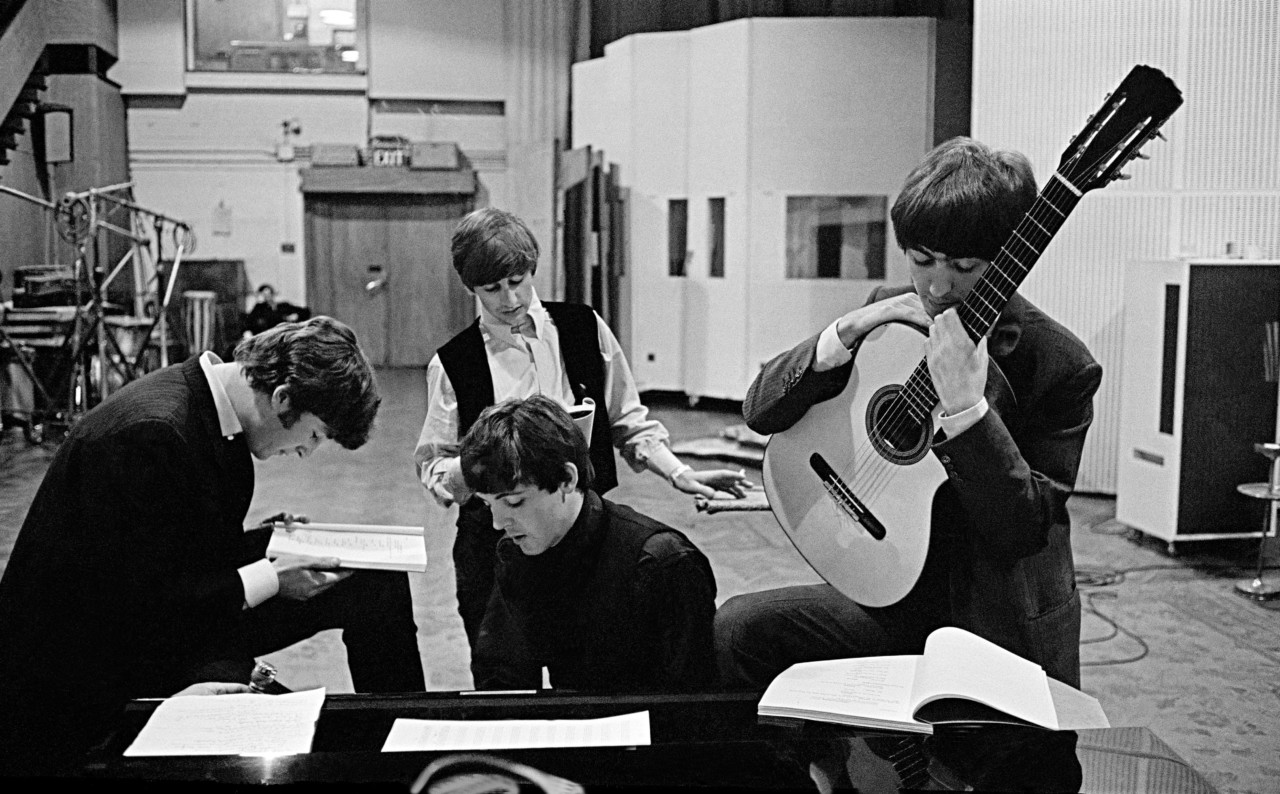

Hurn captured the Fab Four sat around a piano at EMI Studios (which would be renamed Abbey Road Studios a few years later), and he says the photo is a collector’s item, candidly depicting all four members together acting naturally. “In my opinion – and this is absolutely my opinion – I wasn’t sure that they were really that friendly,” he admits. “I only say that because very rarely did you see them together. Of an evening they didn’t all go off and have dinner together. The pictures you normally see of the four of them are posed pictures. Other people would come in from newspapers and would ask them to get together and pose or pull funny faces. I’m not the least bit interested in setting something up; that to me seems like anti-photography in a way.” What’s more, the relationship between Lennon and McCartney was clearly complicated even back in 1964. “I’m not sure that John and Paul really liked each other,” says David. “They were very competitive, which is what made them great writers – and they sparked off each other – but I never got that feeling you sometimes get from four chums together.”

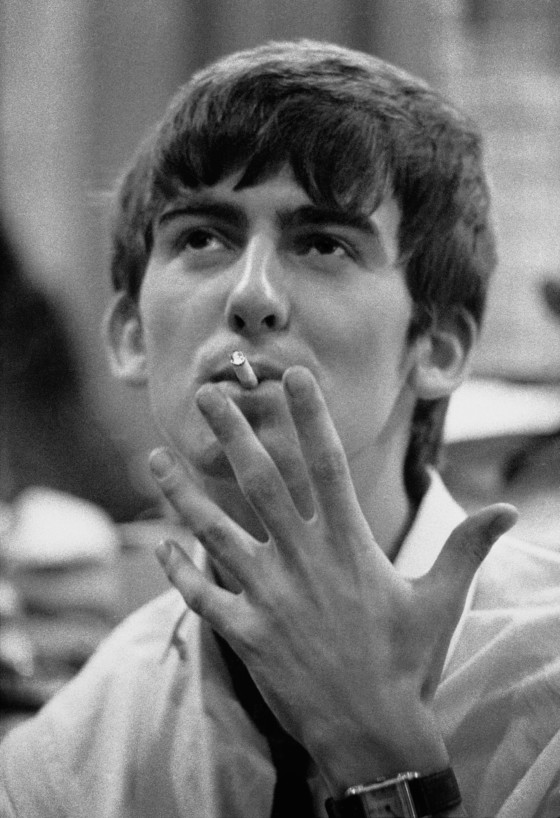

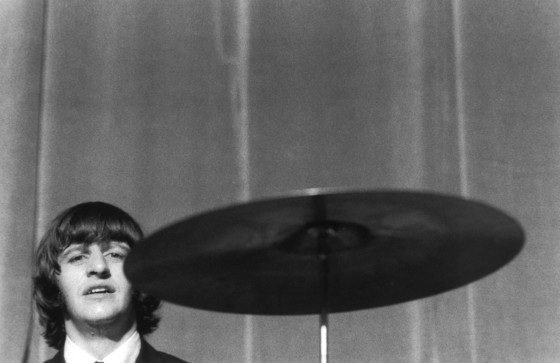

Hern got on best with Ringo, who he spent Christmas with one year. He saw the drummer as the most down-to-earth and the least competitive of the four. “George Harrison wanted to be the best guitarist in the world and went to enormous lengths, charging off to India to learn this, that and the other; and Paul and John wrote the songs and had a kind of rivalry. Ringo was the one left out. I liked him enormously.”

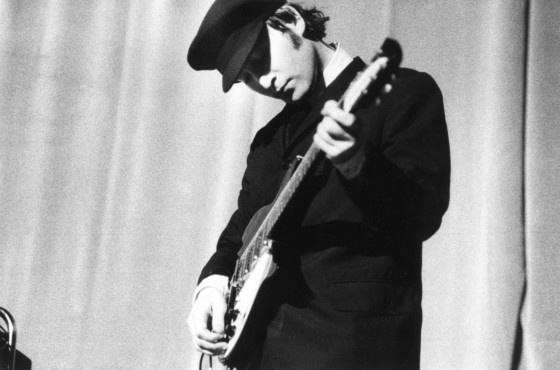

Few countries were immune to their Merseybeat charms, and the hysteria that “the long-haired Beatles” imbued in Rome had a lifelong negative effect on Ferdinando Scianna when he photographed them at the Teatro Adriano in June 1965. “It left me frazzled, I would say disappointed…” he told the Huffington Post in 2014. “You couldn’t even hear the music through all of that chaos and it sounded even worse than I expected. I was so narrow-minded and uptight that it ended up being one of the last rock concerts I ever went to in my life”.

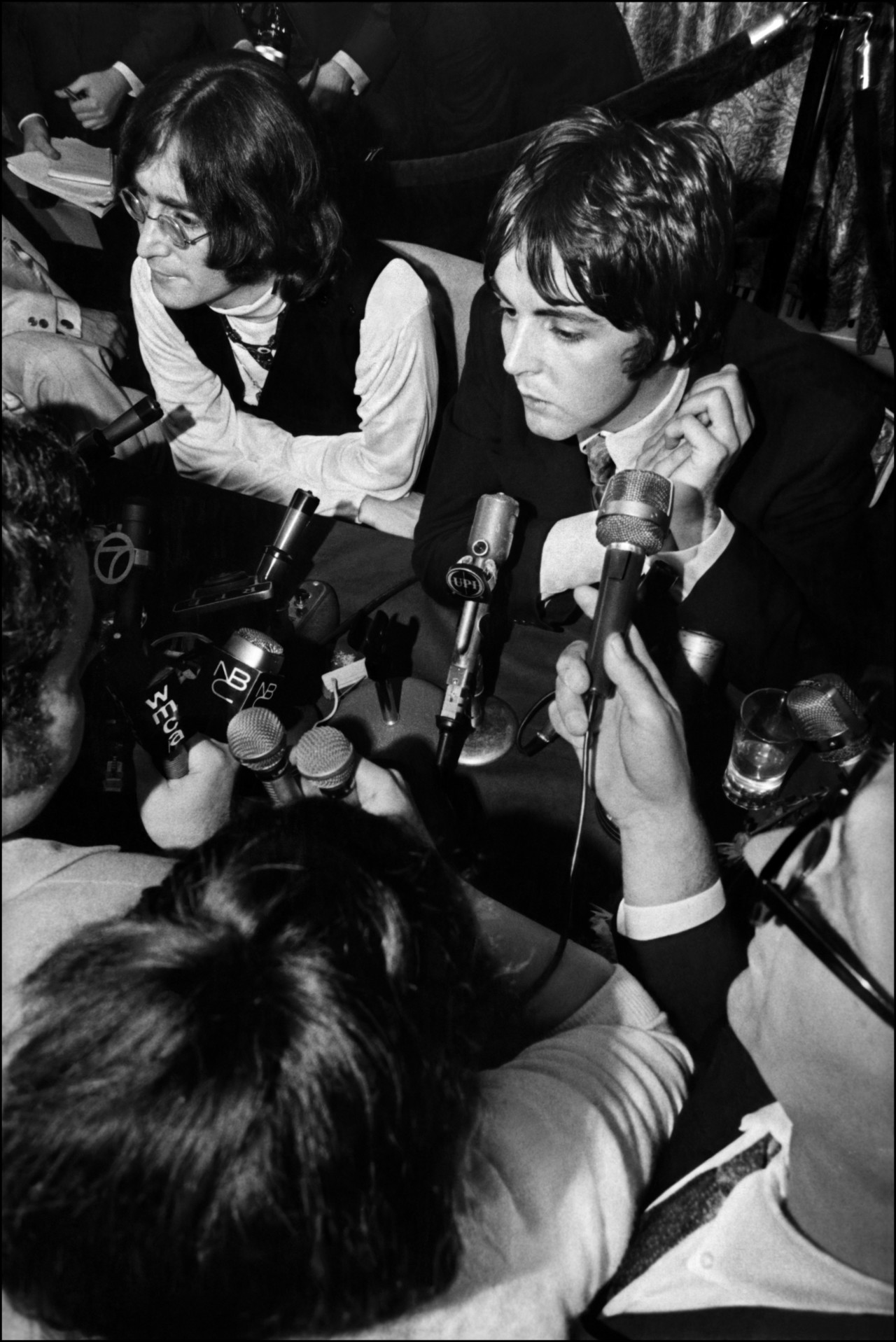

There was less mayhem when Elliott Landy – part of whose archive is represented by Magnum – was called to a Beatles press conference in New York in 1968 as Lennon and McCartney announced the formation of Apple, though the photographers still had to jostle for position. “It was a free-for-all at that time,” says Landy on the phone from his home in Woodstock. “You went and stood wherever you could find a place to stand. As a photographer I never allowed my need to take a picture overcome my need to be a gracious person.”

Landy says his photographic raison d’être was to capture the “essence” of the moment. “I felt the most important photograph was the overall scene: to show the reporters and the photographers shooting the Beatles and demonstrate what it was like for Lennon and McCartney being there. The essence of that situation was that there were these two people besieged by a lot of reporters and photographers trying to get something special from them.” Also during the same press conference, John Lennon suggested the relationship the band had had with the Indian guru Maharishi Mahesh Yogi had been a “mistake”, but Landy admits he has no recollection of what was discussed that day: “When I’m photographing I barely listen, actually. All my brain power is focused on composing the image.”

Landy has two abiding memories. The first involves holding a 22mm lens over the heads of the other photographers to get the shot he’s most proud of: “It’s the one with just the two of them, vertically. To me that image is my favourite because it shows them dealing with the press.” The other memory is of a fellow photographer, Linda Eastman, who he’d gotten to know photographing shows at the Fillmore East venue in New York’s Lower East Side. “At the end of the press conference Lennon and McCartney went into an elevator which was going up and she was with them,” Elliott remembers, chuckling. “She wasn’t taking pictures so I remember that moment. And I thought: ‘Wow, that’s interesting’. It was a total surprise that she knew them at all, but then she married Paul, of course.”

French photographer and documentary maker Raymond Depardon never snapped the Beatles in person, but he was in New York when John Lennon was assassinated in 1980. His short film 10 Minutes of Silence for John Lennon captures a vigil in Central Park where fans had gathered to mourn. “It was a coincidence that I happened to be in New York when I heard about the assassination of John Lennon,” Depardon said, shortly after making the film. He’d seen the upcoming tribute posted around, and headed for the park with a microphone attached to his camera, wandering amongst the crowd away from the throng of press. The film itself is Cageian in as much as the silence isn’t dead silence; there’s background noise and police helicopters hovering above. “I filmed what was around me; the people on the ground who were crying, a whole generation obviously touched by his music.”

At the conclusion of the long moment of silence there’s a spontaneous cheer. “Then people got up, wiped their tears, and we heard Lennon’s music,” said Depardon. “It’s a postcard. A kind of photograph.”