Fall of the Berlin Wall

On the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Wall, we look back at the division of East and West Berlin through the lenses of Magnum photographers

Berlin was partitioned between East and West from August, 1961, when the Soviet-aligned Communist government of the Deutsche Demokratische Republik (DDR), known commonly in the West as East Germany, started to build a wall through the capital – ostensibly to keep Western influence and spies out, but primarily to stem the torrent of its citizens moving westward. Over the following years the Wall went from a piecemeal construction of barbed wire and concrete blocks to a highly militarized ‘death zone’ – frequently mined, with watchtowers, searchlights and multiple layers of wire fencing and walls.

On the evening of November 9, 1989 – after months of signs indicating the weakening of the Soviet-led Eastern Bloc – East German government official Günter Schabowski announced in a press conference that, “Permanent relocations can be done through all border checkpoints between the GDR (East Germany) into the FRG (West Germany) or West Berlin.”

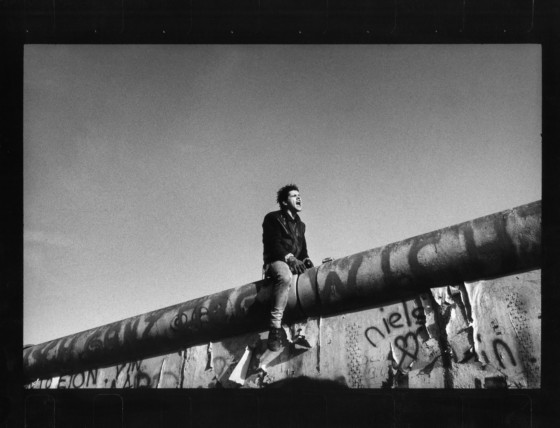

Thousands of Berliners from East and West swarmed around the wall, some chipping mementos from it with hammers and chisels, and there ensued a city-wide party which lasted a number of days, as Berlin revelled in being united for the first time since 1961.

Nearly one year later, on October 3, 1990, the reunification of Germany was made official.

Magnum photographers worked in both East and West Germany, documenting daily life, militarization, social movements and momentous events throughout the Cold War. Here, to mark the anniversary of the fall of the Wall, author Darran Anderson reflects on the Magnum archive on the Wall, and on the division of Berlin.

The work of Magnum photographers on the Berlin Wall forms part of the Magnum Manifesto exhibition, now on show at Compton Verney Art Gallery. More information on the show can be found here.

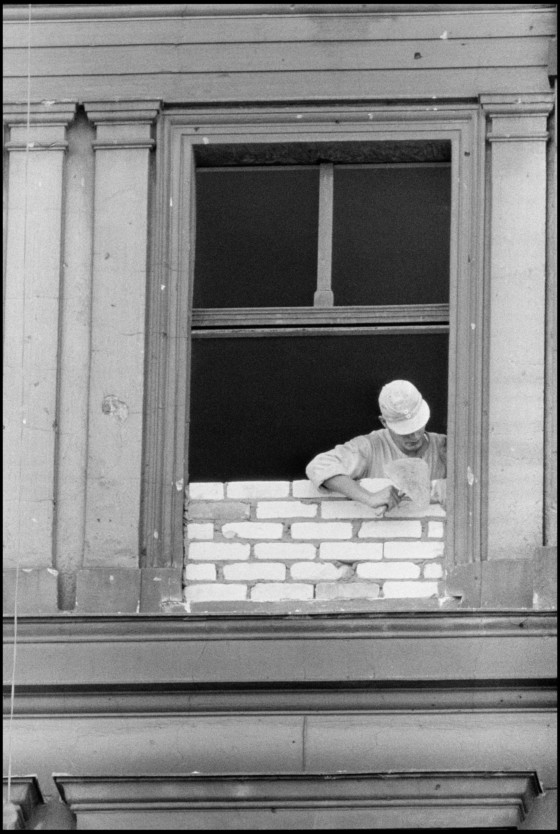

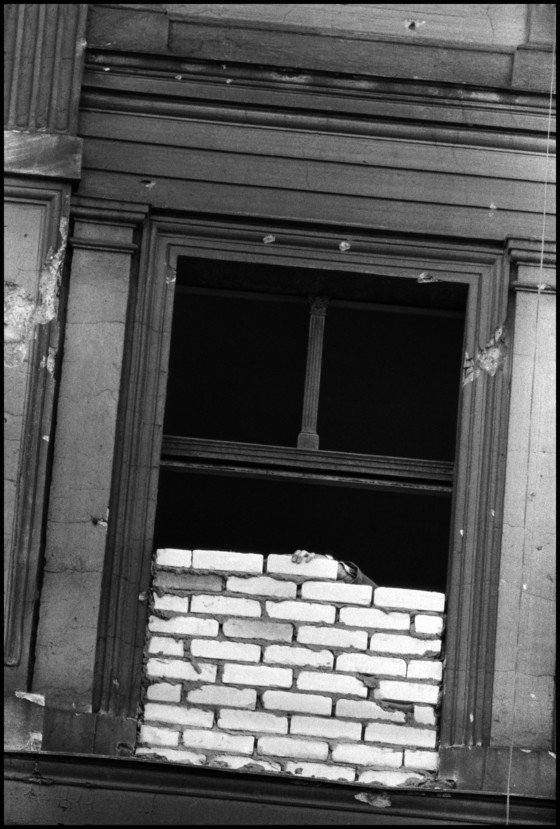

The practice of immurement, being walled up alive, seems to belong to the semi-mythic Dark Ages; more suited to gothic horrors and the legends of medieval saints than the modern world. Yet it occurred here in Europe, within living memory, to millions of people. In Burt Glinn’s photographs of the construction of the Berlin Wall, we see a builder bricking up the window of a building that faces the West. The process seems at once rudimentary and scarcely believable. The surreal nature of the act is emphasized by a later photo that frames a seemingly undead hand grasping the top of the bricks, like something from a Tales from the Crypt comic. It seems grotesque and terrifying for a person to be encased alive, but it takes a particularly callous mix of force and fanaticism to compel a people to wall themselves in.

Bystanders gathered to witness the Berlin Wall rise with a mixture of morbid curiosity and mute disbelief. Glinn’s photographs show them climbing onto heaps of gravel and earth to peer over the barrier as it was being built. Presumably, citizens did so too on the other side of the divide, in the manner of people trying to keep their heads above water. Of course, life would go on, on both sides, and people have the capacity to adapt even to dysfunctionality and tyranny. Walking her dog, a lady passes by, paying little attention to the drama.

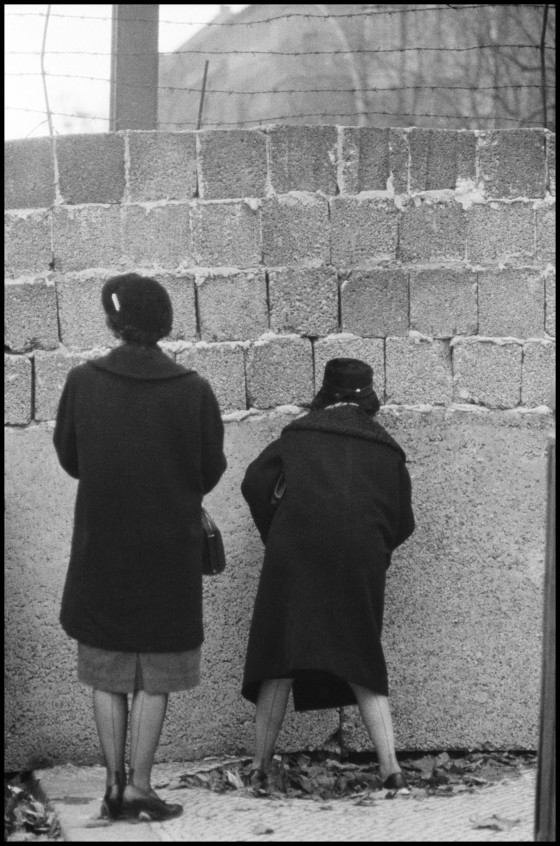

There is a stark contrast between the normality of people’s appearances in the photographs (middle-aged everyday folks with overcoats, hats, handbags) and the abnormality of their situation. Looking closer, they have idiosyncrasies that make them seem as resonant of their time as August Sander’s photos were of his – the old lady using her opera glasses as binoculars, for example. Standing stiffly on the railings, they appear almost to be hovering upright, like René Magritte’s hovering/falling men with bowler hats.

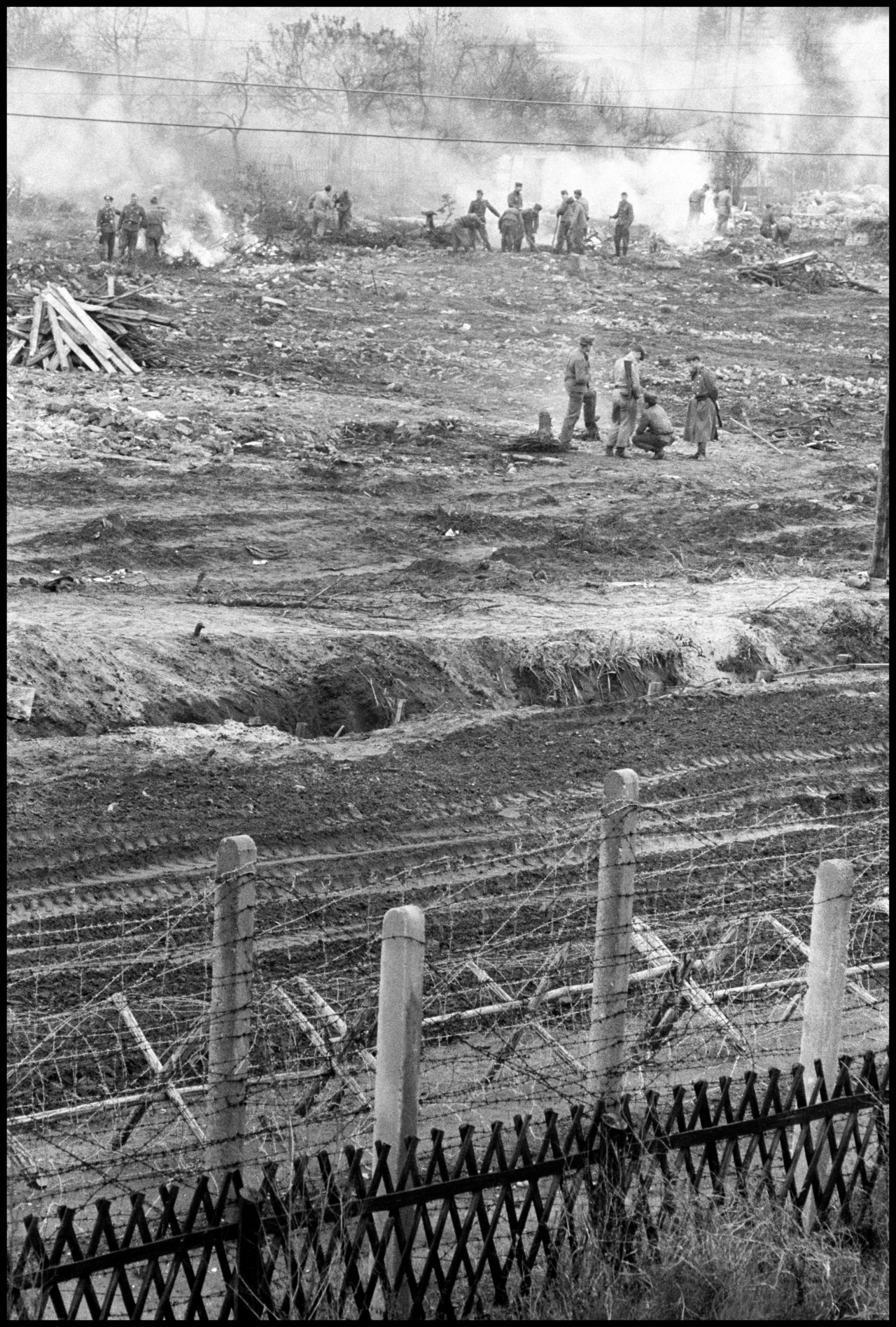

Yet, given their age, they must have already seen all manner of terrible sights, with the Second World War and the rise and fall of the Third Reich. There is an unsettling echo in one of the photographs, depicting the creation of a no man’s land behind the wall, through smoke and across despoiled land, that suggests recent totalitarian horrors such as Katyn Forest and Babi Yar ravine. To the witnesses of the Wall’s construction, this was another stage in history, another example of how ideological faith and brutal geopolitical manoeuvring could make lives miserable and separate person from person. Poignantly, they waved over to the other side; to friends, relatives, other Berliners who were now occupants of another country. They maintained a visual connection until the view was finally obscured with bricks or concrete. It would remain that way for decades.

At certain moments, photographers captured scenes with an eerie prescience. One shot of a woman talking to a friend several floors up at a soon-to-be-blocked window seems simple and innocent in its domesticity. This changes when you consider that the first person to die in the vicinity of the Berlin Wall was Ida Siekmann who jumped from her third floor window in an attempt to flee to the West (firefighters who’d been catching escapees in life nets had not had time to outstretch one before she leaped and she was mortally injured). The image is also indicative of how people casually subvert restrictions. They signal to each other, they talk over distances. There is a wit as well as poignancy to these depictions – the respectable ladies illicitly peering through cracks in the wall for instance, at once buttoned-up and commendably seditious.

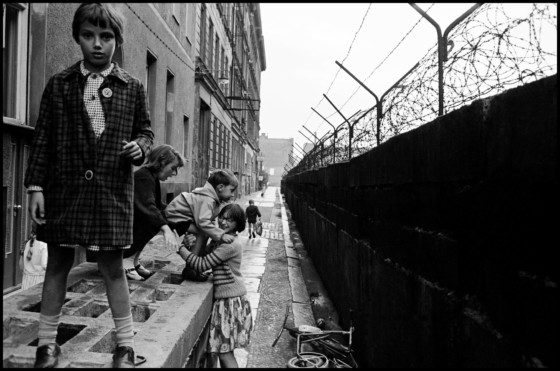

Children, in particular, possess an innate subversiveness and ability to reconfigure with Henri Cartier-Bresson and Leonard Freed both capturing them using the wall as a backdrop to play (with chalk, the wall could become a gallery or a football net). In Thomas Hoepker’s images – which charted the later years of the DDR – a juvenile even uses the Wall as a climbing frame, and engages in some casual vandalism.

Yet the gravity of the Berlin Wall has a warping effect on young lives and minds; consider the sad and troubling mimicry of children, in Raymond Depardon’s photograph, they play on waste-ground building their own wall, complete with rifle-toting sentries. Or the lack of reverence and understanding shown by kids playing football in a memorial to those who were murdered trying to get beyond the frontier.

Then there is the wall itself. It was just bricks, cement, concrete, but it exerted a singular presence as if it was somehow malevolent in character as well as intention. It looms claustrophically as Glinn shoots right up next to it, capturing haunting distant figures on a rooftop, gazing into a different new country formed by the dismemberment of partition. René Burri takes this approach a step further, capturing the Brandenburg Gate from inside a roll of barbed wire. It has a nightmarish quality that accurately implies the latent violence of the place. Yet even with that degree of threat and division, people are resilient and adapt, as Hoepker shows in his image of a father photographing his young sons next to the wall as if it is any other landmark.

"In an early photograph by Leonard Freed, American and Soviet soldiers face off at Checkpoint Charlie at the point where the wall would be placed. It was already there in a sense..."

-

As fearsome and immutable as the Berlin Wall was, its existence was still manmade and contingent. In an early photograph by Freed, American and Soviet soldiers face off at Checkpoint Charlie at the point where the wall would be placed. It was already there in a sense, as an invisible idea, dreamed into existence by politicians. Yet that also meant it could be dreamed back out of existence. In some ways, the wall was easier to sustain than the concept and dissonant reality of the GDR. In Freed’s 1965 photograph, a group of adults and children gaze into East Berlin. The streets beyond are so depopulated they look somewhere between a stage set and limbo. By 1977, in Jean Gaumy’s image, communist Berlin appears almost utopian with the futuristic television tower Fernsehturm and gleaming tower blocks.

This was, however, a workers’ paradise that killed its own workers when they attempted to leave. The true figure of ‘corpse cases’, as the Stasi referred to murdered refugees who’d attempted to scale the perimeter or dig under it, may never be known but hundreds have been verified, (men and women, boys and girls, shot in the back, left to bleed out for the crime of ‘republikflucht’, or ‘deserting the republic’). The last was in 1989, the year the wall came down. Such is the nature of authoritarianism that it is not just the victims that are debased but also the perpetrators. The East German border guards in Peter Marlow’s 1980 photograph may look like dystopian priests of some neo-Inquisition but they are risking their lives with flimsy protection to replace a minefield that keeps the population, including them, from escaping.

"Opposition to the wall was defiantly articulated onto its façade. Graffiti appeared, tentatively at first"

- Darran Anderson

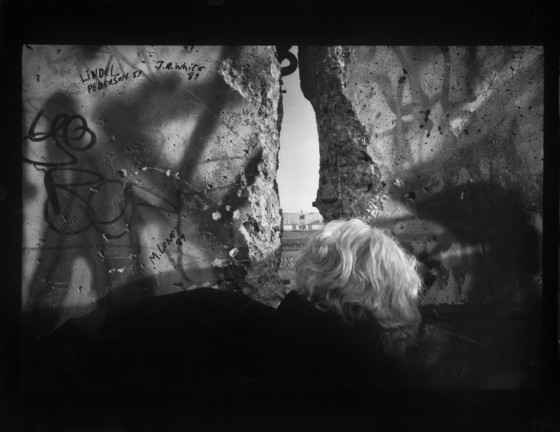

Opposition to the wall was defiantly articulated onto its façade. Graffiti appeared, tentatively at first, before becoming a full-blown expressionistic palimpsest of different colors and layers of writing. As political agitation grew towards the end of the Cold War, the words on the wall seemed to be rising up from the assembled crowds towards the soldiers on the top. By the time of Mark Power’s photographing the Wall – as part of the project that was to become the book Die Mauer Ist Weg – the crowds had conquered the area and the East German soldiers had fallen back to another much more vulnerable line.

At this stage, the wall was doomed. The DDR was morally and economically bankrupt and the momentum of both German populations was against it. That had arguably always been the case, but the East German state could no longer sustain its grip on power or believe its own rhetoric. They certainly lied to the end, claiming the wall could stand for another 100 years. It was much too late. Vast queues of the population formed, heading West. A regime that hid behind the insignia of a hammer and sickle was attacked by its own people armed with hammers and chisels. The existence of the Berlin Wall was bookended with people peering through the cracks, to view a world outside their own. The sheer release and jubilation when relatives, estranged by the wall, met again (as Ian Berry’s photograph shows) was infinitely more convincing than any ideological justification or explanation.

"It would be easy to paint the rise and fall of the Berlin Wall as a tragedy that ended heroically, or as good prevailing over evil, but reality is more complex and troubling than that"

-

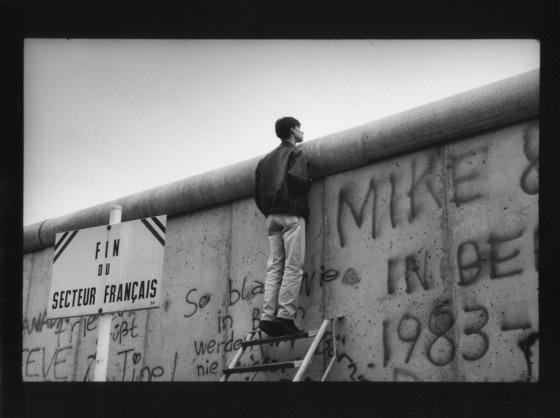

It would be easy to paint the rise and fall of the Berlin Wall as a tragedy that ended heroically, or as good prevailing over evil, but reality is more complex and troubling than that. We can assume the young man in Depardon’s 1989, peering over the wall, faced a future that was better than the past. Things have certainly changed. The death strip, running like a brutal scar through the country, in Peter Marlow’s image, is now the German Green Belt. Germany has gone from being bisected and subject to proxy rule to leading Europe politically and economically. Citizens from the former East have lived with the disappointments of capitalism for so long that a semi-kitsch nostalgia for the old days (‘Ostalgie’) exists. Parts of the Berlin Wall may have been installed across the world as monuments to celebrate the victory of Western capitalism over its mortal enemy but, given history is not remotely finished with us yet, this would be hubristic. Other walls and borders are going up, siege positions are adopted, uncomfortable realities pushed outside. The lessons of the Berlin Wall, and those who chiselled cracks through it to gaze upon what was on the other side, remains just as true now as then.