Yawm al-Firak: Stories of Grief and Separation From the West Bank

Sakir Khader's first museum-based solo exhibition is now showing at Foam in Amsterdam. Warning: this article includes graphic content.

In late February, when Israeli tanks rolled into Jenin and other refugee camps in the occupied West Bank, Western media outlets treated it as a shocking escalation — the first such foray in two decades. But for Sakir Khader, there was nothing novel about it.

“The presence of Israeli tanks and armored vehicles in the West Bank is not new,” he said. “It never was. What’s new is the sudden attention.”

Khader, a Palestinian-Dutch photojournalist, has spent years documenting what much of the world ignores, forgets, or shamelessly attempts to justify. His work resists the flattening of Palestinian suffering into statistics, the erasure of their names, the transformation of grief into just another headline. Yawm al-Firak (Day of Separation), Khader’s first solo exhibition, extends beyond journalism — it’s not simply an exhibition, but an archive that will endure. Curated by Aya Musa, the exhibition runs from February 7 to May 14 at Foam in Amsterdam and follows the release of Khader’s second photobook, Dying to Exist, published in November 2024 by 550BC.

The poem that lends the exhibition its title, an ancient Arabic poem about separation and farewell, has circulated widely in recent years, shared across social media as a tribute to fallen men. “I have seen it played over images of the dead, an elegy woven into the visual language of mourning,” Khader says. “It tells the story of goodbye with an intimacy and emotional weight that feels inescapable.”

Farewell is the thread that runs through Yawm al-Firak. For Khader, it is a word that shows up in all his work and a recurring reality in his personal life. “Farewells in a thousand forms: to the land, not knowing when I will return; to the living, who may not be there the next time I come back; to those who sacrifice themselves for freedom,” he explains.

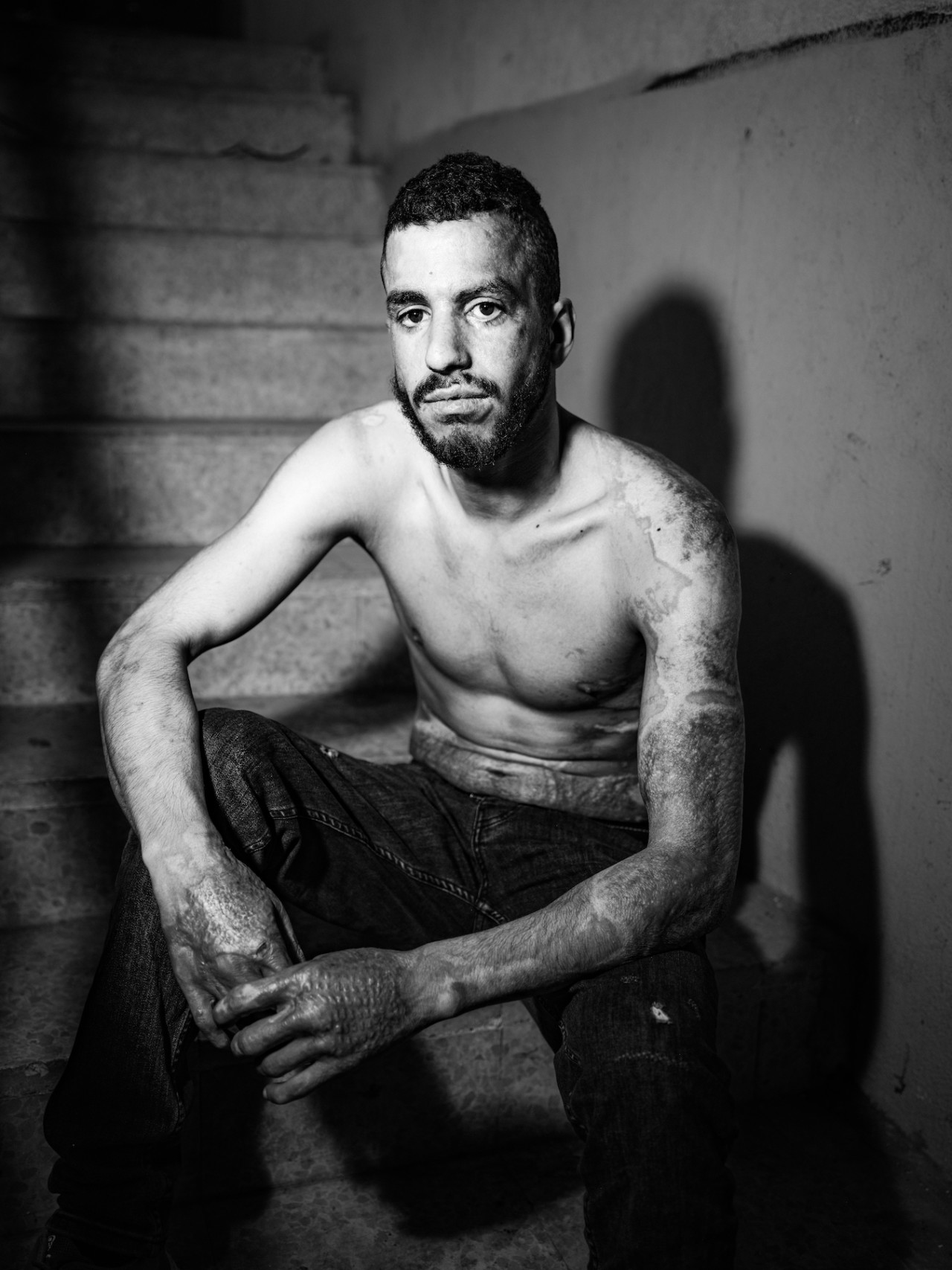

At the core of Yawm al-Firaq are seven portraits of young men going about their everyday lives, gazing toward a future they will never inhabit. Khader has known their families for years. His images show the “fragile boundary between life and death,” as well as the irreversible divide between the present reality and the future stolen from them.

One of the young men, Mahmoud Khaled al-Ar’arawi, was killed in September 2023 by a suicide drone attack on Jenin refugee camp. Another two, brothers Muhammad Ayman Ghazawi and Basel Ayman Ghazawi, were executed in a hospital room when Israeli special forces entered the Ibn Sina hospital disguised as doctors and patients. Their friend, a Hamas affiliate, was also killed. The news described their deaths in a single line: “A terrorist cell eliminated.”

“But if I had been in that room, or you, or anyone else,” Khader said recently on the Dutch late-night talk show Bar Laat, “we would have all been killed. Because to them, everyone is a terrorist.” The first image visitors encounter is a memorial poster of Kosay, Khader’s nephew. Kosay was 11 years old when an Israeli soldier shot and killed him. His death was the catalyst for Khader’s career in journalism and photography.

"It all begins with mothers."

-

Opposite the sons’ portraits, seven portraits of their mothers hang on the wall. Each mother’s name is displayed alongside her son’s. Their eyes meet across the room — the space between them now a permanent chasm. We stand in the midst of irreparable separation.

"First, they bury their own sons. Then, they return to bury the sons of others. The cycle never ends."

-

“It all begins with mothers,” Khader says. “No woman, no man. No woman, no child.”

He has watched these same women return to funeral after funeral: “First, they bury their own sons. Then, they return to bury the sons of others. The cycle never ends.” In addition to photographs, Khader recorded the mothers with his old Hi8, and chose to include the videos at Foam so that exhibition-goers could listen to these women speak about the burden of separation.

For three of the sons, a final portrait was possible. For the four others, it was not. Three of their bodies were taken by the Israeli military and never returned. One was so severely disfigured that his mother refused to allow a photograph to be displayed. In place of these missing portraits, Khader has used lithophane prints — delicate, three-dimensional reliefs that reveal an image through light and shadow. Now, even in their absence, they remain.

On February 6, more than 1500 people lined the streets outside Foam, waiting to enter Yawm al-Firak. The museum had not anticipated the overwhelming turnout. Lines stretched beyond the entrance, wrapping around the building. Once inside, the crowd was confronted by images of young men whose futures had been stolen and the grieving mothers they left behind.

Khader was joined by Palestinian-Dutch poet and actor Ramsey Nasr, who gave a speech. “It was a beautiful evening,” said Khader. “To see so many people come, to witness my work, to stand together in this moment.” But for him, there is relief in letting go, too. “The work is no longer mine alone — it is out in the world, beyond my hands, carried by those who see it.”

Still, one absence loomed, “I only wish the mothers I photographed could be here, could witness the opening, could stand before the public and share their stories themselves,” he explains. Ultimately, his work is not about him, it is about those whose voices and stories are so often silenced or ignored.

Khader expressed gratitude toward Aya Musa, Senior Curator at Foam, “not just as an extraordinary curator, but as a brother. He approached everything with the utmost care and respect. I learned so much from the process, and that, too, is something I cherish — this experience of collaboration, of creating something larger than myself.”

At the exhibition’s entrance, visitors pass under a deeply personal item that bears an unfathomable toll: a burial shroud inscribed with the names of 235 journalists killed in Gaza between October 2023 and February 6, 2025 — a number that continues to rise. The fabric is Khader’s own kaffan, the Islamic burial cloth he keeps ready in case he is killed on assignment.

“Ordinarily, a mortuary shroud is reserved for those who pass from natural causes — those who succumb to heart failure or slip away peacefully after a long life,” Khader said. “They are wrapped in white sheets, carried by their loved ones to the graveyard, their departure marked by quiet reverence. In times of war, a martyr is buried in the clothes he was wearing at the moment of his death. There is no time for ceremonial preparation. He is lifted by the hands of his family, carried toward eternity in the fabric of his final moments.”

“But in genocide, when the dead are uncountable, when bodies are not merely stilled but shattered, burial becomes something else entirely. The remains — fragments of what was once whole — are gathered, wrapped in cloth,” says Khader. “Often, there is no one left to carry them. No loved ones to bear the weight of grief, no hands to lower them gently into the earth.”

“This shroud stands for all my colleagues who were brutally killed by Israeli forces while showing the world the reality of Gaza under attack,” he said. “Now, in a way, when you enter my exhibition, you must pass through the shroud — to be confronted by the toll of genocide, the weight of absence, and the haunting presence of death.”

Khader’s work stands apart from the narratives often found in Western media, where Palestinians are framed either as nameless victims or as threats. His images challenge that reduction, with the perspective not of an outsider looking in, but of someone who belongs, who understands the language, both spoken and unspoken.

“I am Palestinian, and I speak the language — not just in words, but in emotions. I understand the culture, the unspoken nuances, the weight of history carried in a glance,” he said. “My camera only emerges when people are comfortable enough with my presence. I invest in relationships first.”

"I do not capture to observe; I capture to preserve. To ensure that we remain in the archive, that we are never erased."

-

“I want to understand people, to know what moves in their hearts, to look beyond their eyes — because in their eyes, if you are permitted entry, you glimpse the truth of their emotions. The difference between me and some journalists — though, of course, there are those who seek the human story rather than the accolades — is that I do not see my people as subjects for my work. I am not a journalist. I am a visual artist, documenting not just our existence but the depth of our pain, the resilience embedded in our souls, the unwavering love for the land.”

This approach reimagines the dynamic between the photographer and the photographed. “The mothers in my exhibition could be my own mother. I could be their son,” he explains. “Because I do not see them as subjects — I see them as my people.”

"I refuse to portray us solely as victims. We resist, we endure."

-

“I refuse to portray us solely as victims. We resist, we endure. And yes, that resilience comes at a cost — we mourn, we suffer, we lose — but suffering and steadfastness are entwined. Hardship fortifies. The more they try to uproot us, the deeper we root ourselves, beyond the reach of any military bulldozer. Our existence is immovable. This is why my gaze — my way of seeing — is different from many Western perspectives. I do not capture to observe; I capture to preserve. To ensure that we remain in the archive, that we are never erased.”

In his latest book Perfect Victims, Palestinian writer Mohammed el-Kurd writes, “Zionism is the leading cause of death in occupied Palestine,” Even before October 7, Gaza and the West Bank have been forced to deal with devastation and destruction on an unimaginable scale. Israeli soldiers and settlers have murdered, imprisoned, and displaced Palestinians in staggering numbers for close to eight decades. While these abuses did not begin on October 7, they escalated and expanded.

“There is no battle in Jenin,” Khader said. “There is only destruction. The Israeli military is not engaging in combat; it is bulldozing, looting, burning homes. The fight is not between two armies. It is between the Israeli military and Palestinian infrastructure itself.”

This, more than anything, is why Yawm al-Firak exists. It is an archive of lives that would otherwise be erased. It is an act of preservation and a commitment to the people who are still living there, still resisting occupation, and still remembering all that’s been lost. Their, and our, refusal to forget is a refusal to look away — a responsibility to bear witness and seek justice.

Khader hopes the exhibition reaches those who have never truly seen Palestine before. “What I always hope is that people who know little about Palestine, or those who hold a fixed perspective, allow themselves to be confronted with a reality rarely seen in major Western institutions like Foam.”

On March 17, after repeatedly violating commitments under the ceasefire, the Israeli military resumed its full-fledged bombing of Gaza, killing and wounding hundreds of Palestinians, including many children. This comes after more than 17 months of genocide, life-saving aid blockage, and forced starvation in the Strip, and months of escalating violence and displacement in the occupied West Bank.

When asked what he wishes people understood about Palestine, Khader was adamant. “Yes, we are victims — of an oppressing force, of tyranny, of Western policies. But we are also a people of the land, refusing to be uprooted, our existence woven into the very soil. They can kill us, but they cannot erase us.”

Khader’s work repudiates history dictated by the powerful. It is a reminder that no matter how many sons, daughters, mothers, and fathers are lost, Palestine remains. “Our blood has already seeped into the earth, absorbed into its core. It has been spilled across mountains and olive groves, yet we remain.” He continued, “No decree, no plan, no proclamation — no matter who drafts it — can alter that truth. We exist, and we will exist forever.”

As Yawm al-Firak continues, Khader is nearing completion of his next project — a long-form documentary about Syria, a story he has been following for over a decade. “It’s a story of resistance, of survival, and of what comes after the battle fades but the consequences remain.”

No matter what follows, Khader’s focus remains steadfast. “I document not just for the present, but for the archives, for the future, for the history that is still being written.”

“Yawm al-Firak (Day of Separation)” runs at Foam in Amsterdam from February 7 to May 14, 2025. On April 6 and May 4, Khader will give a guided artist tour of the exhibition, where he will share the stories and experiences behind many of the photographs.