A World In Color: Italy in Motion

A new selection of unseen images pays homage to Italy, an unwavering muse for Magnum photographers throughout the decades

Our journey continues through Magnum’s unexplored color library archive in Paris with the second installation of A World in Color. In partnership with Fujifilm and MPP (the Heritage and Photography Library of Paris), A World in Color is an ongoing project to digitize the vast color library, which has remained dormant for decades. Magnum’s Archive and Production teams have been digitizing thousands of unseen slides with the help of the Fujifilm large format GFX system, making them visible to the public for the first time.

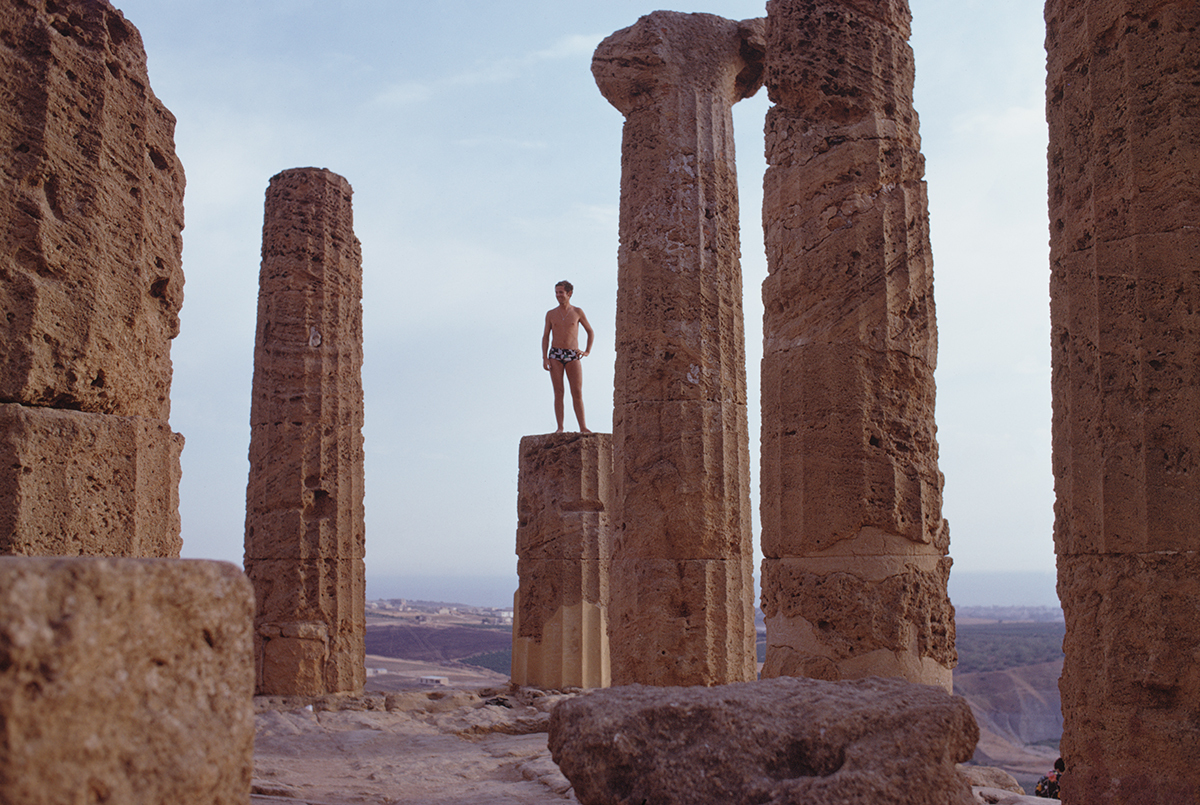

This month, we venture to Italy, an enduring source of inspiration for Magnum since the agency’s creation. For decades, Magnum photographers have traveled to Italy, capturing a certain cultural “intelligence circulating in the streets like a vivid bloodstream,” as Italian writer Natalia Ginzburg wrote. These images represent the subtle alchemy of photographing spontaneous moments within Italy’s layered past. Their immediacy both surprises and challenges convention. Many of the photographers in this selection are known or remembered for their work in black and white. Yet here, from Sardinian islands to the Adriatic Coast, is Italy in vibrant color.

In early September 1944, in a euphoric, bewildered Paris just days after its liberation, photo editor John Morris recognized a man getting out of an army car. It was Polish photographer David “Chim” Seymour. “He was flabbergasted,” Morris recalled. “He asked, ‘Is Capa alive?’ He also asked about Henri.” Three years later, Chim would co-found the Magnum cooperative with the very same Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Capa, along with George Rodger, William and Rita Vandivert, and Maria Eisner. Capa and Rodger struck up a friendship while documenting the American troops landing in Sicily and the Allies recapturing a severely-bombed Naples in October 1943. Morris himself would join as Magnum’s first executive editor.

Having lost both of his parents and other family members in the war, Chim sought refuge in Italy. In 1949, Rome became his main residence between his wide-ranging projects.

“Almost everybody looked forward to going to Rome because of Chim,” Burt Glinn said. Chim’s apartment was near the Hotel d’Inghilterra, which, according to Glinn, soon became “Magnum’s office.” It was on Chim’s initiative that Italy became a haven for Magnum photographers in the chilling shadow of the war. A country on the mend — the heart of neorealism and the latest stomping ground for American film — Italy beckoned as a dynamic escape.

In 1956, the same year Chim was tragically killed by machine gun fire in Egypt, the 27-year-old American photographer Leonard Freed arrived in Rome on his first assignment for Look magazine. It was the year that sparked two long-term love affairs: one with his future wife and printer, Brigitte Klück, and the other with Italy itself. Brigitte told The New York Times that, after Freed had crossed the Alps on a scooter to track her down in Dortmund, she asked him about the art of printing. Freed insinuated that the job wasn’t for women. “Women can’t do that?” she thought. “Right. I went out and bought a darkroom.” She would remain his printer for decades to come.

Freed made about 45 separate trips to Italy in his lifetime, shooting mostly with 35mm and 50mm lenses. His life’s work resonates with a profound, steadfast affection for the country, which he photographed until two years before his death. In his introduction to Freed’s posthumously published photo book, The Italians, Michael Miller writes that Freed documented Italy’s deep-rooted rural traditions as a “self-healing quest” to uncover his own relationship with his Jewish ancestry. While The Italians is exclusively in black and white, these revived images capture the pulse of 1970s Italy in its full color palette.

According to his daughter, Freed found his angles — like this close focus from behind near Favignana, off the coast of Marsala, Sicily — by moving around quickly, albeit discreetly, often concealing his camera. He eventually covered his Leica in stickers so that it appeared less invasive.*

This fly-on-the-wall approach is also evident in his photograph taken the same year of a communist meeting in Bologna, then the symbolic “capital” of the Italian Communist Party. The gentle beams of sunlight warming the men’s backs (he judged light exposure by eye, never by meter, according to Miller) evokes a painting, Freed’s first medium. On the wall between Marx and Lenin is a self-referential touch: the seminal 1963 portrait of Che Guevara by Magnum’s René Burri. The meeting takes place in the thick of the Anni di Piombo, or “Years of Lead,” a period from the late 1960s to the early 1980s that was plagued by terrorist attacks across the political spectrum. Five years after Freed’s picture was taken, Bologna Centrale railway station was bombed, killing 85 people and injuring over 200.

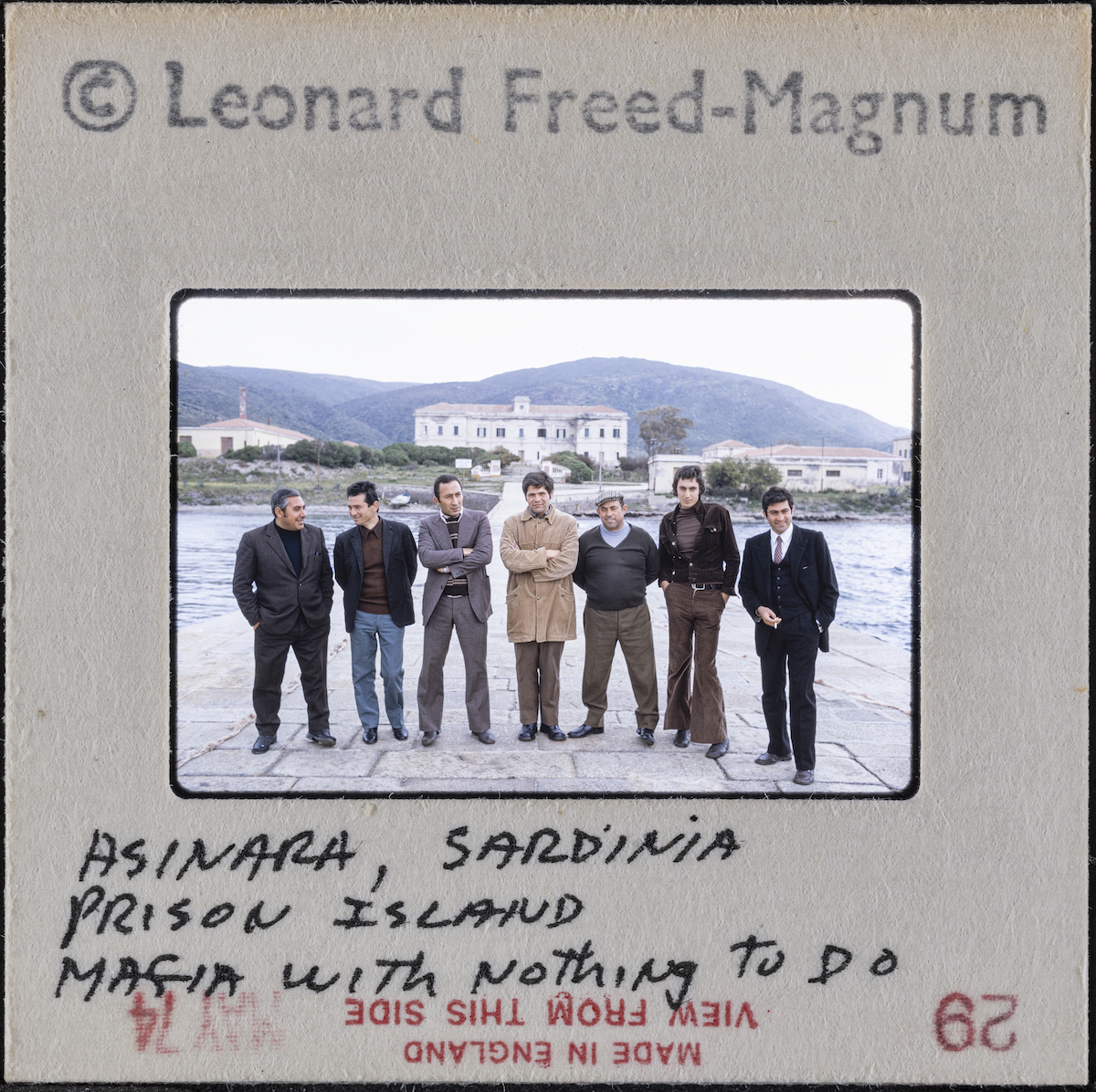

The previous year, Freed ventured to Asinara, an isolated island off the northwest tip of Sardinia, where he photographed convicted members of the Mafia. Elegantly dressed, the mafiosi in Freed’s group portrait appear uneasy “with nothing to do,” as Freed notes, like school boys in a class picture. Established in 1971, the island’s maximum security prison facilitated the state’s crack-down on organized crime.

“The place was reminiscent of hell,” said former prisoner Carmelo Musumeci. Renato Curcio, the founder and leader of the ultra-leftist Brigate Rosse (Red Brigades) — the group responsible for kidnapping and murdering the Italian Prime Minister Aldo Moro in 1978 — was imprisoned there in 1976. The infamous “boss of bosses” of the Cosa Nostra, Totò Riina, was held in solitary confinement there in 1993. Since the prison’s closure in 1997, the island has enjoyed its status as a national park, where wild donkeys graze on its rocky cliffs.

For Freed, Italy provided a dynamic cultural timeline embedded in human behaviors and trajectories. He wrote in his journal, “What do I want to say in my photos of Rome? I am looking for tradition, […] where we came from and where we are going, not as in the modern western world where we’re always in the present, and we’ve misplaced ourselves […].”

Richard Kalvar is fascinated by yet another remnant of Italy’s past: gestures. “Gestures are two extra instruments in a conversation. Where is a better place for people using gestures than Italy? For me it was a kind of paradise.” He adds, “I’m trying to make something out of what I’m seeing, and in Italy there is a particularly rich soup.”

In 1981, he found himself outside of Naples for an unusual assignment: “a tomato scandal, where the farmers were getting subsidies from the EU based on totally fictitious information.” Kalvar and a journalist tried to track down the farms involved, but “no matter who we asked, it was always somewhere else,” he said. “There was certainly a comic edge to our trip.”

Exploring on his own terms, which he says results in his “most serious work,” Kalvar stumbled upon a carnival in Montemarano, a small village in Campania. There, he photographed a group of singers appearing as timeless performers in harmonious alignment. Composition, Kalvar says, is essential “if you want the picture to be believable.” He explains: “Photography looks like reality. But reality is continuous, it has no limits, no frame, it moves, it makes noise, it has odors. A photograph is an image of reality. In any case it’s going to be limited, so why not play with that idea, the impression of reality.” In 2011, Kalvar joined nine Magnum photographers in documenting the country for the 150th anniversary of its unification.

About a decade before Kalvar crossed Campania, Dennis Stock had a revelation. He was in Umbria, reading the “Canticle of the Sun” by St. Francis of Assisi. The text brought upon a “total commitment and enchantment” to pursue the sun as a photographic theme. After years of photographing Hollywood icons and jazz musicians in black and white, Stock turned towards nature for his “inspiration and education,” and color became a vital conduit for his vision. These photos culminated in his 1974 book Brother Sun, taking the name from Saint Francis’s canticle.

With this creative shift, a new approach emerged. He wrote that the camera becomes “an extension of my body […] until an acceptable vision merges us all — the machine, nature, and me.”

Elsewhere in this selection, life unfolds in bouquets of color, and Italy never stops moving. Ferdinando Scianna, who has extensively documented his home island of Sicily as well as poverty in Naples, captured an Easter procession in Marsala, which takes its cues from sacred representations in the Middle Ages.

Gueorgui Pinkhassov captures a statuesque woman against the vivid facades of Ponte dei Frari, across from the Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, one of Venice’s most treasured churches.

In 1958, Burt Glinn photographed a group of raucous boys surveyed by nuns, their black habits in stunning opposition with the blindingly white sand and the Adriatic sea (see second image). Later, in 1963, Glinn captured a Neapolitan fishermen erupting in laughter (below).

Among German-born Erich Hartmann’s far-reaching photographic themes — from the aftermath of WWII, which his family narrowly escaped in 1938, to the daily ritual of bread-making — were the enigmatic effects of photographic experimentation. Here, Hartmann’s “vortograph,” as Ezra Pound called images made with kaleidoscope lenses, offers a surreal portrayal of a gondolier (below).

These relics from the archive provide a visual time capsule of Italy’s spirit, rendered all the more present in striking color, each a meditation on seizing a spontaneous moment in the country’s past. As one of Freed’s subjects said after he photographed her and her friends on the street, “Now you have made us immortal!”

Live Events

Join us on May 10–11, when Magnum travels to the Torneria Tortona in Milan, host of the second FUJIKINA event for A World in Color, organized by Fujifilm Italia. Curated by Magnum photographer Alec Soth, the exhibition will reveal a new set of unseen images spotlighting Italy, and original slide sheets from the Paris color library archive. Soth will also present his own series of new photographs and video commissioned for the event, using a FUJIFILM GFX100 II. Drawing inspiration from Erich Hartmann’s experimental series of Venice and Stock’s photos of the Hotel Danieli, Soth visits the same Venetian hotel, transforming it into a camera obscura. Evading all clichés, Soth immerses us in the Venice of his imagination.

FUJIKINA MILAN

TORNERIA TORTONA,

Via Tortona 32, 20144, Milan

May 10-11, 2025

With Alec Soth

Book your tickets here

*From Sylvia Magna’s interview with Elke Susannah, Freed’s daughter.