All of Life is Here at Home

Magnum photographers depict scenes of intimacy and tenderness in everyday settings

There is a photograph in the Magnum archive of the photographer Robert Frank and his painter wife Mary slow-dancing in the kitchen of their Valencian home, taken by Elliott Erwitt in the summer of 1952. She is barefoot and wearing an apron; he is clothed in loose trousers made for warm days, with the cuffs rolled up at the ankles. Their cheeks brush gently against one another, palms pressed, her arm around his neck, and the afternoon sun throws long shadows across the tiled floor. Erwitt stands apart from the couple, framing their moment from the other side of the doorway. It is such a simple domestic scene, but so filled with the profound tenderness Erwitt was able to find in ordinary moments and illuminate in his photographs.

Broad-ranging restrictions as a result of the pandemic left many of us with all the more opportunity to notice moments like these and appreciate their emotional weight in ways we did not previously. Day-to-day life changed, and slowed down, allowing each of us to figure out our own ways to spend this time and take care of ourselves and the people we love. Artists across the world dug into their archives, constructing still lives with the materials of home and noticing the beauty of accidental compositions and small gestures. At Magnum, photographers made new work to document what their own quarantine situations looked like — meanwhile, the Magnum archive itself is full of inspiration from across the decades that show what spending time at home can teach us about photography. A constellation of those pictures are collected here.

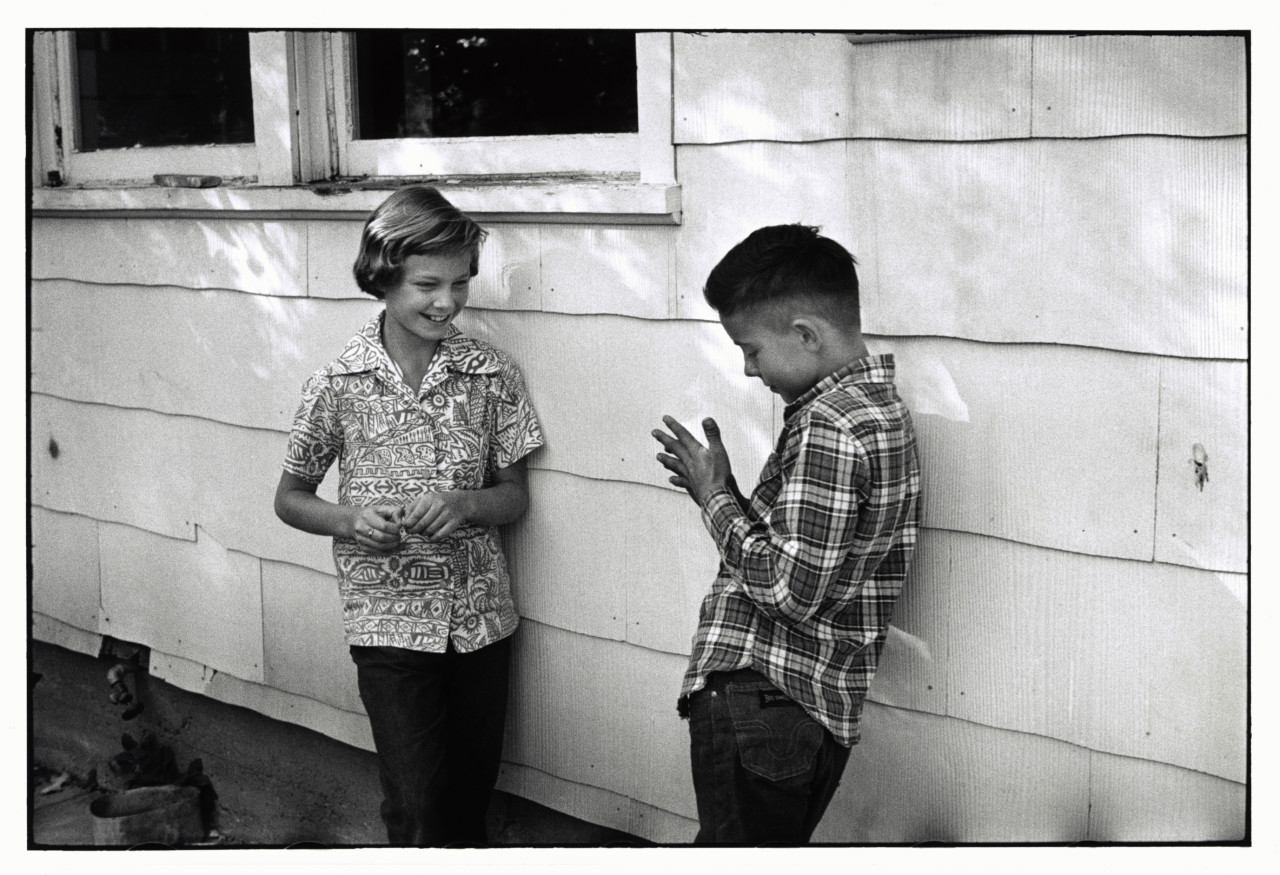

In another of Erwitt’s images, two young boys lean against the shady side of a house in Wyoming in the 1950s, chatting and laughing together. It’s a picture reminiscent of those long summers knocking about with the neighbourhood kids in gardens and on the street. Gardens turn up often in the work of Magnum photographers, as wonderfully aesthetic places in which to make portraits of people passing time. In 1964, Bruno Barbey photographed two women sitting among their plants in Paris. Enri Canaj photographed the Ameha family playing in the courtyard garden of their Addis Ababa home on a Sunday afternoon in 2017,

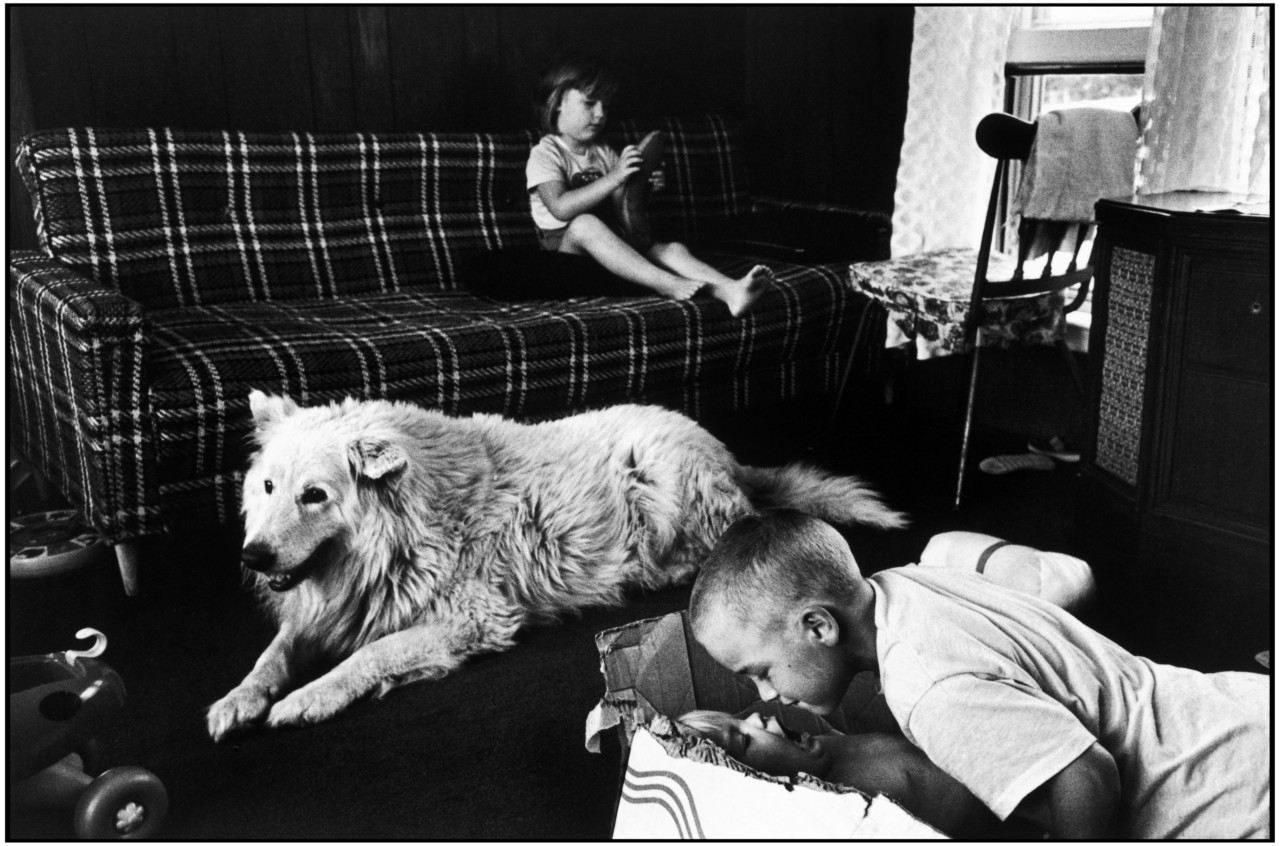

A particular Martine Franck photograph shows the dog and children of a Long Island fisherman’s family tumbling over sofas and floors in the living room. Another living room image, taken by Chris Steele-Perkins in 2014, shows the Ogunmokun family. It’s part of Steele-Perkins’ project, The New Londoners, which aimed to document inhabitants of the UK capital whose heritage originated from every country in the world. “All the families were deliberately shot in their own homes – that was the common denominator,” says the photographer. “As they were people I had never met before – only communicated by phone or email – I wanted them to be as relaxed as possible, so in their own homes not in a studio, and I wanted clues to who they were from the clothes they wore and the way they decorated their homes, particularly their living rooms.”

At times, the photographers stand outside and shoot back into the house, because windows have long held an enduring allure for photographers as frames within the frames of photographs. Here, two images by Gregory Halpern and Jonas Bendiksen respectively capture life unfolding beyond the glass. As windows frame moments, so too do the doorways of a house, as the Erwitt picture showed us. In a 2010 story entitled Women Changing India, Patrick Zachmann took a photograph of Anuya Kulkarni at home in Maharashtra with her husband Ashok Kulkarni; he stands in the background bathed in blue light while she is in the foreground, laughing in a pink dress. It’s almost like two portraits, split by a yellow painted doorway.

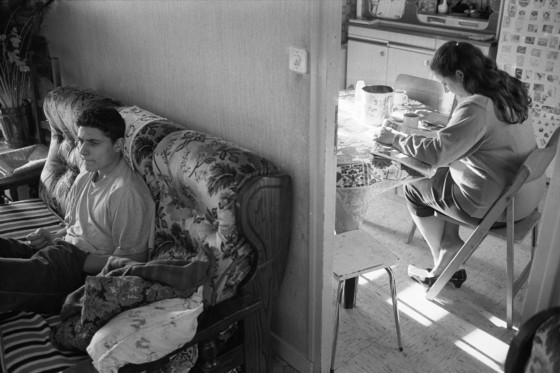

Zachmann’s photograph finds a sort of sister image in a shot by Richard Kalvar, taken in France in 1997. A son watches television in the living room while through a doorway, his mother has coffee in the kitchen; two different moments unfolding in one picture once again. On the attractions of photographing private everyday moments, the photographer has the following to say: “Sometimes I’m sympathetic. Sometimes I’m curious. Sometimes I’m nosy. Sometimes a scene unexpectedly opens up that I think I can capture and make into an interesting photograph. Sometimes I’m on assignment. Sometimes I’m with friends and know that I can play around without bothering anybody. Sometimes I’m excited by a smile, a frown, a look, a feeling.” Further back in the 1970s, Kalvar shot the close-knit English mining community of Warsop Vale at their Nottinghamshire homes, and in those photographs we see the locals whiling away time chatting to neighbours over fences in their backyards, and perching their young children on low brick walls. “The photograph is completely abstracted from life, yet it looks like life,” he once mused. “That is what has always excited me about photography.”

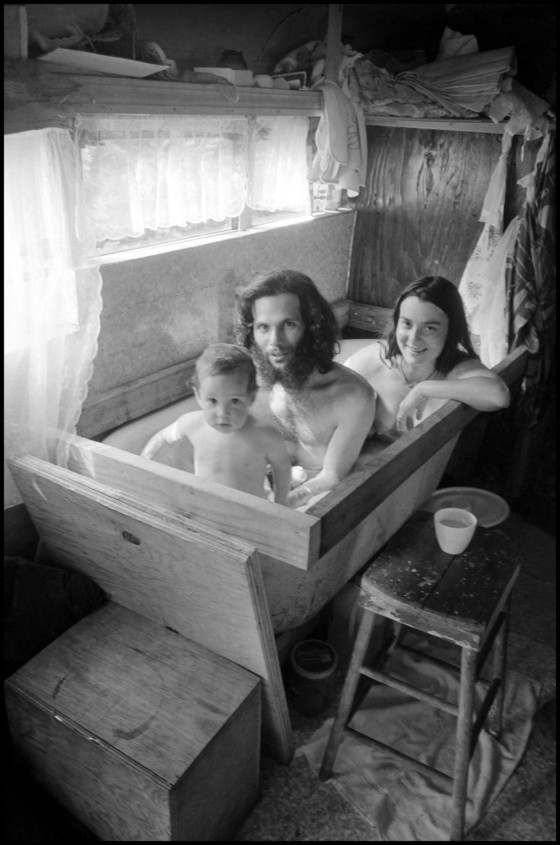

Dennis Stock recorded scenes of domesticity of a radically different bent, in his 1960s work focusing on the heart of the optimistic – but soon-to-be fractured – alternative societies of America. Stock followed hippie movements, consisting largely of former residents of urban centres such as San Francisco and New York, as they settled in communes in the countryside and attempted to establish new ways of living.

Olivia Arthur recorded intimate moments in the home in her 2009 project Jeddah Diary. “The first things I saw in Saudi were the big empty roads and houses with impossibly high walls,” she says. “Everything seemed to be happening somewhere else, out of sight, behind closed doors.” During her time in Jeddah in the early 2010s, Arthur stayed in a women’s hostel, but she wasn’t allowed to take pictures of the women without them wearing their abayas. Therefore we see pictures of the women in their abayas sitting on the floor socialising and playing games, or swinging their legs idly from kitchen countertops. In the pictures they aren’t wearing them, Arthur has found other ways to obscure their faces, with heads turned away, out of shot or covered in reflection bursts. “I had been sent to Jeddah to teach a workshop for local women photographers. My students introduced me to bits of their world, and gradually I made friends and came back again,” she remembers. Slowly whole worlds – ‘bubble-words’ as Arthur calls them – opened up to her, in homes rarely unsealed to the eyes of outsiders. Arthur would go on to create the project Waiting for Lorelai, focusing on her experiences at home, anticipating the birth of her second daughter.

"...we see pictures of the women in their abayas sitting on the floor socialising and playing games, or swinging their legs idly from kitchen countertops."

-

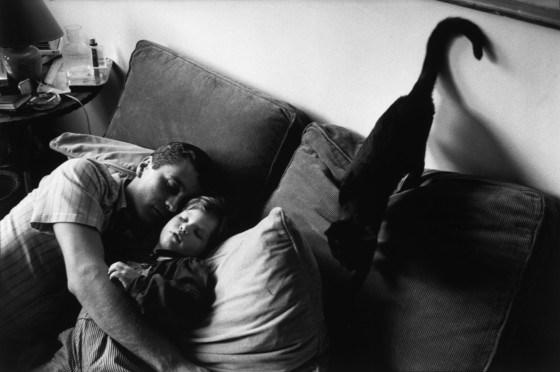

Kalvar also made a number of endearing sofa studies across the decades, and in his pictures we see siblings piled onto the sofa watching television, and people curled up taking naps together. Scenes from sofas proliferate across the Magnum archive, revealing moments of real tenderness and intimacy between subjects. Jacob Au Sobol makes a quiet portrait of Sabine Maqe stretched out on her sofa in Greenland.

“People keep talking about how this pandemic has made them change their process. for me it has made no difference, because of these photos at home. By staying indoors now and working within those limitations, I feel like I’m experiencing something familiar but something that I had experienced quite some time ago.” So says Sohrab Hura about the work he made in his Sweet Life series. Life is Elsewhere and Look It’s Getting Sunny Outside!!!, the first and second chapters of the work respectively, form a personal project made after Hura’s mother was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia in 1999. While the first book, in black and white, was constructed from fragmentary depictions of his life and friends alongside his images of family, the second book, in color, focused more closely on documenting his relationship with his mother and her illness through their everyday life at home, with their dog Elsa, over a period of six years.

Alex Webb has collected images of lazy afternoons spent on porches and verandas. In a particularly iconic shot of Webb’s, Miskito children in Nicaragua sit hunched against one another on their porch in thoughtful reverie, gazing in opposite directions, a vivid green parrot perched upon one of the boys’ heads. Meanwhile, an image from Alec Soth’s I Know How Furiously Your Heart is Beating — a portrait of Nick from Los Angeles lounging on a fur-covered bed— merges the exterior and interior scenes of his home. Soth is known for shooting the intimate lives of modern Americans across the country in projects like Sleeping By the Mississippi and Niagara.

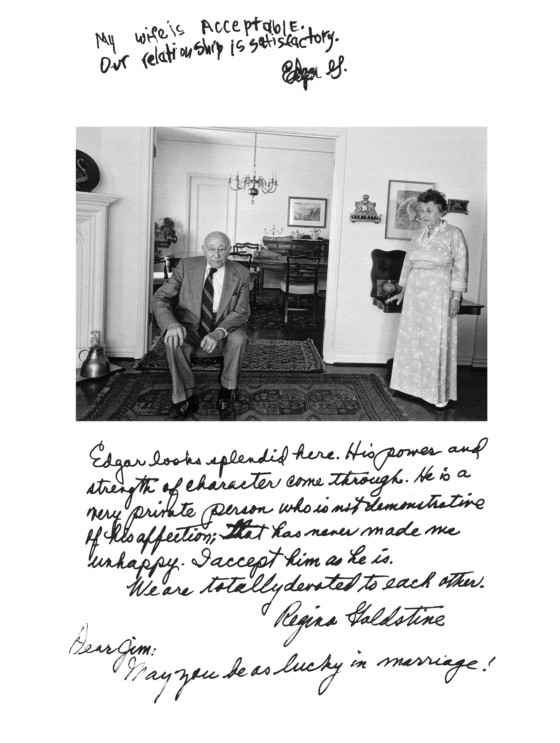

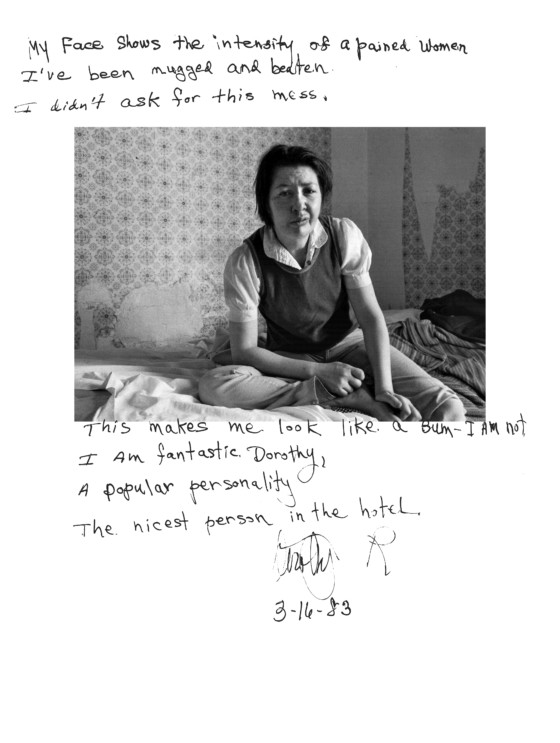

Jim Goldberg’s project, Rich and Poor, set out to document economic disparity in the US through portraiture of San Francisco residents who occupied two extremes of wealth. Goldberg documented these people in their homes and gave the black and white photographs he made back to his sitters, inviting them to add to the images with their own handwritten testimonies — a technique he has continued to use throughout his practice. Goldberg’s interest in the interior lives of others, as expressed through their homes, is seen again in 2018’s Darrell and Patricia, Goldberg’s series documenting a transgender couple living in Portland, in which photographs from the couple’s personal collections are enscribed with their annotations and accompanied by his images representing details of the couple’s living space.

In his seminal project The World From My Front Porch, Larry Towell edited his own pictures of his wife and young sons with archival family photographs, objects and song lyrics, piecing together a visual story of their long family history in rural Ontario. The houses they built and the land around his home are characters as much as each of his family members, and in many of the pictures we see fields stretched out behind family moments, or light pouring through the windows; outside always folding in.

Like Towell, Christopher Anderson began trying to locate “an emotional moment that is pure” in every photograph he takes when documenting the first few months of his son Atlas’ life. These images, taken at his parents’ place and then later at the Brooklyn loft he and his wife Marion lived in, focus on the little rituals of daily care – cuddles and cleaning teeth, Marion and Atlas bathing together, her shaving and him sleeping. They aren’t dramatic, nor do they feature any of the political impetus of some of Anderson’s other projects, but for him, as with many of the other photographers here, observing the quiet humanity of family life taught him invaluable lessons about taking pictures. As his son got older, and his own father aged and grew sick, he explains that making this work showed him “what is at the heart of a photograph”, wherever in the world, whatever the subject, and it’s something he’s carried forward for the rest of his career. “Everything I had been doing up until this point I had been doing to prepare me to make these pictures now,” he said, back when he was just beginning the great project of documenting home. “These are the most important pictures that I will make in my lifetime.”

David Alan Harvey echoes that sentiment. He’s shot teenagers in France, the elderly fisherwomen of South Korea and travelled extensively through the Americas, but “no matter where I am,” he once said, “I’m always bringing up in my hard drive my sense of home.” In one particularly stirring image a young girl of no more than seven or eight stands next to Harvey on a balcony in apartment blocks thrown up in Cuba on the Baracoa shorefront in the 1990s. She squints up at his camera, a small smile on her lips. Harvey, far from home, found familiarity in that moment. “As a young boy with a camera, all I had to photograph was my home, my family and a few blocks radius around our house. I was simply an aspiring photographer with a dream.” Of course, that dream did come true for him, and he works as a photographer now. “And yet,” he added, “even while I might be sitting at a sidewalk café in Paris, in the back of my mind I am thinking of my front porch in the Outer Banks of North Carolina.” There are always those little associative circles that lead us back home.

Emin Ozmen’s photograph of 65-year-old Mehmet Sirin picking figs from a tree in his garden in Suceken, Turkey is a particularly affecting one. Mehmet knows his time left at this place is brief, because his house will soon be lost underwater to make way for one of 22 dams to be built as part of the gargantuan hydroelectric Southeastern Anatolia Project. Ozmen captures him appreciating the things his home has given him in those last days.

For all of their travels across the world, the extended times away, putting their lives on the line and shooting the events that have made history, captured hearts and changed lives, each of these photographers is united too in the remarkably humanist ability to slow their gaze, and reflect, through images, on how home shapes us. In gardens and greenhouses, baths and beds, the quiet theatre of the everyday plays out in the images collected here; moments both subtle and significant, painful and poignant wrapped up together in that muddled, messy way that only home knows.