Uncovering Pompeii: How the past continues to unfold at the Roman ruin site

Darran Anderson speaks to Patrick Zachmann about his work photographing the new archaeological dig

For well over a thousand years, the Roman city of Pompeii lay buried under layers of pumice and ash. The society of its time was preserved like a time capsule by the pyroclastic flow from Mount Vesuvius in AD79. Amidst its preserved architecture, Pompeii’s inhabitants were captured writhing in their death agonies, while its culture and religion survived in the form of art and graffiti, both sacred and profane. Yet as much as the place was suspended in time, it serves as a powerful example of how history is not fixed but has the potential to change with new discoveries. Rather than inert and complete, the past is continually unfolding the more we uncover.

Magnum photographer Patrick Zachmann has been on hand to document the remarkable recent findings at the site, uncovered by the Great Pompeii Project. Having travelled the world for decades, undertaking acclaimed projects from Colombia to China, Zachmann is now engaged in something approaching time travel at Pompeii. His work in Pompeii shows that, to a thrilling and eerie degree, the past is still with us, a point he is keen to emphasise, “It’s not dead but rather it’s permanently revealing itself and changing our conception of what happened long ago. I took a photograph, for example, of some [newly discovered] writing on a wall, which shows us that the eruption of Vesuvius happened around two months later than we thought. These discoveries could continue for a long time because this is a small part of an area that has still not been searched, partly because it costs a lot to secure the site beforehand.”

"It’s an exciting thing to bear witness to, and a real privilege. I really wouldn’t have thought I could be touched by that, but I am."

- Patrick Zachmann

Zachmann was there when some of the most stunning recent finds took place, being among the first people to set eyes on them in almost two thousand years. It was an experience, he found surprisingly moving, “I saw a horse unearthed recently, in November. They’d already found one and made a moulding but then I was there to witness the moment when they discovered another, lying just beside the previous one. That was really something, you know? It’s an exciting thing to bear witness to, and a real privilege. I really wouldn’t have thought I could be touched by that, but I am.”

The project at first appears something of a departure for Zachmann, whose work has been more directly people-focused in the past but he quickly found he was drawn to it, “I could say that it’s by accident that I became involved in the Pompeii project. I’ve not really been a photographer committed to archaeology. I like to photograph people and people’s lives. So it’s quite unusual for me. One of my best friends is a producer of television documentaries and he invited me to have a look. And I fell in love with the process, with the team, with what I saw.”

"These discoveries could continue for a long time because this is a small part of an area that has still not been searched"

- Patrick Zachmann

“The documentary film I’m simultaneously working on in Naples is connected with the photo-essay I did there in the 1982 on the Camorra and the police. Those are very different places to move between. That site in Pompeii, where the excavations take place, is very quiet. It’s private, I could even say it’s secret, as the public are not allowed to enter. Everything is secured. It’s very hard to get in, to get permission. Even the public side is quiet actually. So, it’s very different from Naples.”

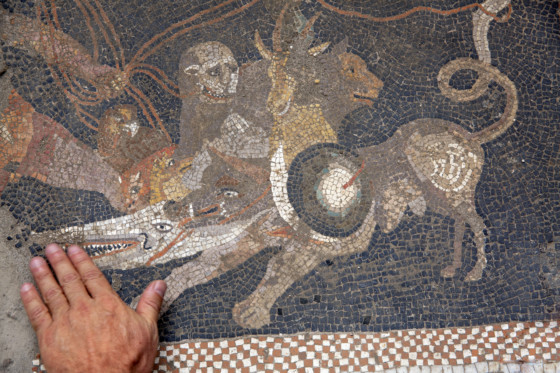

While stylistically or thematically different from his earlier work, there are other deeper ways in which Pompeii has resonated with Zachmann, linking back to his previous projects, “One year ago, for Christmas, I went with my wife from Naples to Pompeii to visit the public site and actually I was not that impressed. There were so many tourists. For me, that side was a little bit dead. I’m not interested in monuments and stones and things like that, but the new excavations are completely different. For one thing, there is a very important team of workers, archaeologists, and architects, so it’s very much alive. They are revealing entire houses and frescoes, mosaics and objects. Digging them out from the ground, from the past, bringing it all to life. That’s the difference. The frescoes are so colorful and beautiful and vivid that I thought it would be a pity to photograph them in black and white. I wanted to make this process very alive, and color contributed to that.”

"For all the resurrecting of a bustling society, there is also a haunting sense of mortality at Pompeii, given this society was halted devastatingly in its tracks by the volcanic eruption."

- Darran Anderson

For all the resurrecting of a bustling society, there is also a haunting sense of mortality at Pompeii, given this society was halted devastatingly in its tracks by the volcanic eruption. “It reminds me of a movie I did in Chile almost two decades ago,” Zachmann notes “on the traces of Pinochet, after he was arrested. I followed a forensic archaeologist, trying to find the bones of the disappeared victims of his regime, gathering the bones to make skeletons, to finally give the bodies of loved ones lost during the dictatorship to their families. At that time, I was interested in the parallel between photography and this process. In Pompeii, it’s a little bit the same; those archaeologists are digging up the memory of this lost past. It almost resembles a crime scene, two thousand years later. All these people are taking so much care with the artefacts, the bones, using their hands and their tools delicately so as not to break anything.”

“The photographic process is also very similar. You take a picture and the scene then disappears from reality. The moment we took the picture is already somewhere in the past. It is not alive any more. And then you rediscover it in the photographs. Before digital photography, this feeling was even stronger as you processed the films and then the picture would reappear in the dark room, in the water, like memory.”

This balance between life and death is reflected in the differences between Zachmann’s portraits of the workers and the landscape they operate within, “I really enjoy photographing the team, the archaeologists, the director of the site Massimo Osanna, who is a very passionate character. It’s thanks to him that those new excavations can happen. I like to get along with all the workers. I feel close to them. The community is part of the story. On the other hand, I also enjoy taking landscape shots of the site, very early in the morning because the light is perfect and it has a deep sense of mystery. The team protect the stones and the frescoes with large white shrouds. They remind me sometimes of ghosts.”

"The moment we took the picture is already somewhere in the past. It is not alive any more."

- Patrick Zachmann

Being the first to photograph the discoveries has made Zachmann reflect on the changing nature of photography and his place within it. “Today, we struggle with the notion of uniqueness or exclusivity. I have concerns now about the landscape of photographic information. In the age of social media and camera phones, discoveries are shared immediately, and all the world will come in one day. That’s not something I really care much about. I hate to be in a scene surrounded by other photographers. I hate to be in the middle of a scene surrounded by other photographers. I remember Henri Cartier-Bresson reflecting on this phenomenon, he was one of the few photographers to witness Ghandi’s funeral. But now the situation has changed, and with the Gilets Jaunes in Paris, for example, there are so many photographers you don’t feel the need to go there. Photography, for me, is a question of necessity. When I decide to involve myself in a project or subject, to go to a country, it’s to discover first, then to understand, and to find the story through pictures. If I don’t feel that necessity, why go?”

This desire to venture in the opposite direction to the crowd has been evident in Zachmann’s work from the beginning. “I always try to be in a different place. To try to reveal to the public a reality they don’t know. When everyone was going to Lebanon during the war, I chose Naples. I am not a war photographer, but I knew that I was young and I needed to confront myself with violence. I read just a few sentences in a daily newspaper about a gang war there but at that time nobody really knew about the Camorra in Europe and it’s really with that story that we started. That’s always the process. Now it’s just more difficult.”

In an age, where everything seems to be photographed all the time, it requires certain approaches and skills to rise above the noise. “One thing I’ve noticed,” Zachmann points out “is that we are more and more focused on storytelling; to be different from the millions of pictures a day online. I have always been like that, so I didn’t wait for this big change. It is a way to show reality in a different way, in a deeper way, with a personal input. For me, it’s a story. I’ve been going there many times so Pompeii is a story not just of the new excavations but the evolution of these discoveries and the people working there. I’m not very much interested in single decisive images. Of course, like any photographer, I’m trying to take great pictures and I’m glad when I get one, but that’s not enough. I like to tell a story. And contextualise it. That is why I also make films. For me, that’s logical. I’m a storyteller.”

A new film by Pierre Stine and produced by Stéphane Millière on the new excavation is currently in process. It is a coproduction of Gedeon Programmes with France Televisions, RTBF, AT Production with the participation of Curiosity Stream.