Alex Majoli on Artists and the Rewards of Environmental Portraiture

The photographer discusses environmental portraiture, responding to and reflecting a subject's mood and work, and the rewards of meeting artists in their own studios

At 15, Alex Majoli joined the F45 bottega in Ravenna, Italy, working as an apprentice under Daniele Casadio. “I grew up in the studio, which specialized in art reproduction,” Majoli recalls. “Many times my master asked me to go to the studios of the artists while they were working to complete the catalogues. I learned that the place where one should take a picture of an artist is in their studio.”

The wisdom that an artist might best be understood situated within the environs in which they create has served Majoli extraordinarily well over the years. Although not primarily a portrait photographer, Majoli’s sensitivity to the complex interplay between his subjects’ inner worlds and outer lives has made him a gifted portraitist of leading contemporary artists.

In the new book Magnum Artists: Great Photographers Meet Great Artists, the title’s author and editor Simon Bainbridge brings together portraits by Magnum members of more than 100 of the most innovative artists of the past century. From Edward Steichen, Man Ray, and Marcel Duchamp to William Eggleston, Nan Goldin, and Naim June Paik, Magnum Artists offers an intimate look at a diverse array of men and women who have transformed the course of Western art.

Majoli’s environmental portraits reveal the collaborative nature of his approach and the importance of developing a space for mutual engagement between artist and sitter in the creative process. Whether photographing with Marina Abramović, Yayoi Kusama, Shirin Neshat, Ron Gorchov, James Rosenquist, Sophia Calle, Carrie Mae Weems, or Ellsworth Kelly, Majoli possesses the ability to distill the essence of each artist to reveal the space where mind, spirit, and body become one.

Majoli approaches each of his subjects from a place of discovery. He follows no template or technique, preferring to allow his subjects and the environment to inform the shape the portrait will take. “If you go to an established photographer, the sitter knows they are going to look fantastic and great, and the result has already been written before they take a picture,” Majoli says. “The artists saw my photography, and some of my conceptual work. They were excited because maybe they didn’t know what I would come up with. Sometimes they would be skeptical, but they were also intrigued and interested in being more experimental.”

For Majoli, dialogue is a critical part of the portrait process, be it through a conversation or shared activities. “Even when I have my camera in front of a person, the person can collaborate with me by suggesting a set-up they would like to try,” he says. “We go from there to another place — that is the best part: just to be free to express ourselves. It has to be a picture of two people, not only one. Then the cross-over of two personalities materializes in the work.”

The results are a series of portraits that stand at the intersection of two creative minds, allowing each portrait to stand apart from one another by offering a unique, often-unexpected insight into the spirit of the subject. Majoli’s portraits of Sophie Calle made for La Repubblica in 2011 depict extraordinary scenes of the French writer, photographer, installation and conceptual artist in her home and studio, a space as eccentric as the woman herself. Located in Malakoff, a suburb south of Paris where Calle has lived and worked since 1979, the studio has transformed from a warehouse-like space into what she describes as a “zoo of taxidermy,” featureing a tiger, giraffe, peacock, monkey, foxes, and two large bull’s heads, which appear in one of Majoli’s portraits. “Sophie Calle’s a collector. Her work is all about collection investigations that are less pictorial and all about thinking,” Majoli observes. “You can fall in love with any man or woman, any artist you photograph, because they are so brilliant of mind.”

"It has to be a picture of two people, not only one. Then the cross-over of two personalities materializes in the work."

- Alex Majoli

Similarly, Majoli’s 2009 portraits of the Iranian visual artist Shirin Neshat evoke her visual language: renowned for investigating the dialects of binary thinking that inform our notions of East and West, feminine and masculine, public and private, and present and past. “Shirin Neshat is so beautiful, fragile, and silent. She was dressed in black with painted eyes that reminded me of a cat,” Majoli recalls. “Her home was a minimal place in Soho [in New York] with beautiful light. I tried to [create some] symbiosis and translate what I saw. I entered her place: it was white, she was dressed in black, and the work is black and white. It came naturally to do what I did there.”

It was a very different encounter compared to Majoli’s experience photographing Marina Abramović for American Vogue when the “grandmother of performance art” was living in Rome in 2005. “That was a more glamorous shoot. There was a stylist on the set who came with some cutting-edge clothes. We spent a day together and had fun. She is a performer and this was evident on the shoot. I was thinking more about the glamour side than the artist side when I took those pictures. We walked through Rome and she was ringing bells at her friends’ homes asking, ‘Can we take a picture here?’ She also wanted kitsch: an image of her on a Vespa in front of the Colosseum, which was all her idea. I am not really into that,” Majoli says with a laugh. “The others were much more of a collaboration.”

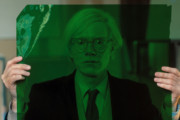

Majoli is adept in dealing with strong personalities, recognizing that within their expression something deeper reveals itself, as is the case in his 2012 portrait of American artist James Rosenquist. Majoli met the early proponent of Pop Art in his Florida studio half a century after his first solo exhibition and inclusion in the landmark ‘New Realists’ show at Sidney Janis Gallery where his work appeared alongside Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and Claes Oldenburg’s.

“You don’t do so much with Rosenquist — he is a volcano of energy,” says Majoli. In an explanation of the intent, demanding look on Rosenquist’s face, he remembers, “He was cracking jokes from the first moment of the day, and even making jokes about how his studio burned down years before all his work caught on fire. He was so immersed in what he was doing, I had to ask, ‘Can you stop for a second? Really. I need to take a picture.’ He said, ‘Yeah come on take the picture. I have to paint.’”

“I asked him what he thought about [another artist’s] work that seemed to copy his in a certain way,” Majoli continues, “and he said, ‘You know Alex, everybody has a mother. My mother oversaw me when I was young to wake up early in the morning and work hard. His mother says, ‘Wake up the morning and copy James Rosenquist.’” Majoli laughs, delighted at the memory of Rosenquist’s unquenchable pith. “I’m so glad I met these people. What a privilege!”

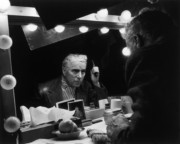

A striking counterpoint to that rollicking meeting was the time Majoli spent with American painter, sculptor, and printmaker Ellsworth Kelly in the artist’s 20,000-square-foot Spencertown studio in upstate New York in 2012. By this time, Kelly — best known for his hard-edge, minimalist works made in the Color Field style during the mid 20th century — was in his late 80s. There, Majoli’s approach to portraiture was just as pared back as the works of the artist himself, encapsulating Kelly’s simple color palette that underscores the geometry of forms.

“Ellsworth Kelly is shy, completely gentle, and really calm. He uses crutches and usually needs to be seated, but was walking around the studio with his oxygen tank, which he had taken off for the photograph. He gave me a lot,” Majoli says. “I love that picture. It’s not really the standard image someone would take or publish. It was dark and he was backlit, but I saw something, and I asked, ‘Can you stop, please?’ He gave me all the time and was super sweet.”

Despite the differences of subject, style, medium, and approach among the many artists Majoli met and photographed, he discovered they all shared the same passion to create. “It was a lesson that made me realize the market side is a completely different world,” he says. “Yayoi Kusama, I think she doesn’t even know what they are doing with the paintings, she just does them. As an artist… you wake up in the morning and do what you feel. They keep the flame of creativity focused on the art, rather than how much money they could make with it. I feel like even if they got $1 a day, they would have the same passion and dedication. I am sure — I saw that.”