“Art is not documentation, it is interpretation”

Miguel Rio Branco discusses the allure of multidisciplinary work, art versus style, and the intrinsic baseness of humanity

‘Art is art’, declared Miguel Rio Branco in a 2012 interview, and this broad view still seems the best way of trying to comprehend his oeuvre. He is variously a documentary photographer, filmmaker, painter, installation artist, and sculptor; critics have long tried to classify his multidisciplinary approach. In response, Rio Branco classifies himself as ‘marginal’, as someone who exists on the fringes of society. And, interestingly, most of his work leans toward what happens in these margins, what takes place in the liminal zone between nature and technology, and the contrast and hypocrisy present in contemporary society.

Born in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria in 1946, the son of diplomats, Rio Branco had his first exhibition in Bern, Switzerland, in 1974. He lived in Portugal, the USA, and Brazil — where he remains today. His long career allowed for his artistic practice to evolve, transform, and constantly question itself. Since 2006 he has lived and worked in Araras, the rural area outside Petrópolis (in the state of Rio de Janeiro) — this is perhaps no surprise for someone who has repeatedly criticized and analyzed modern cities around the world.

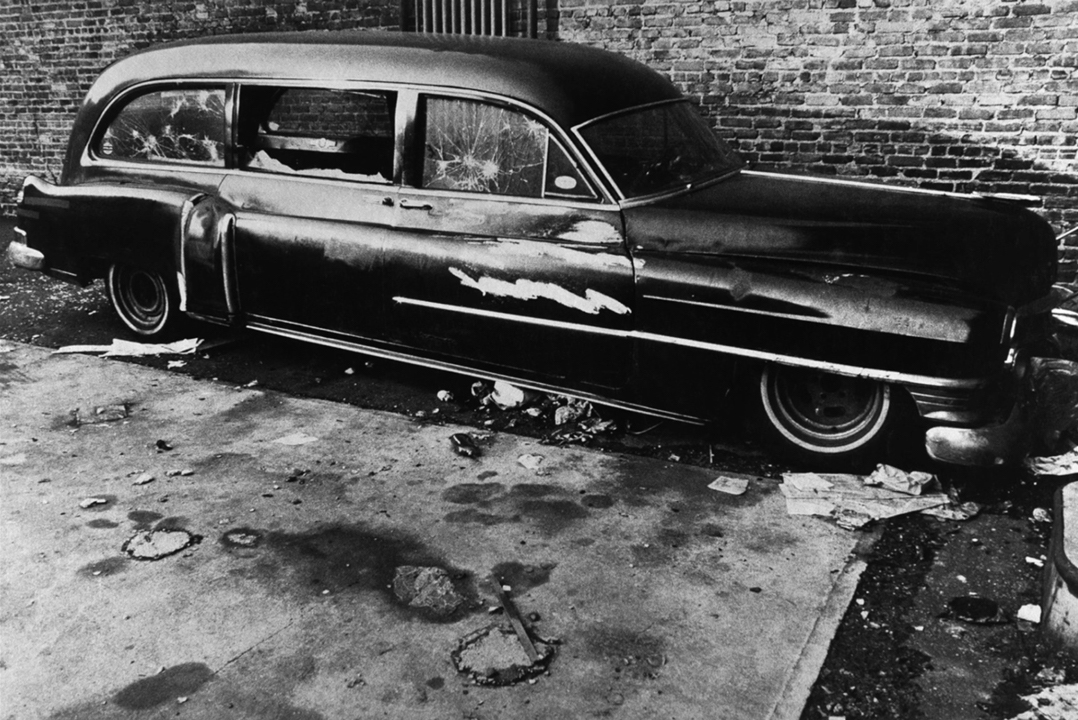

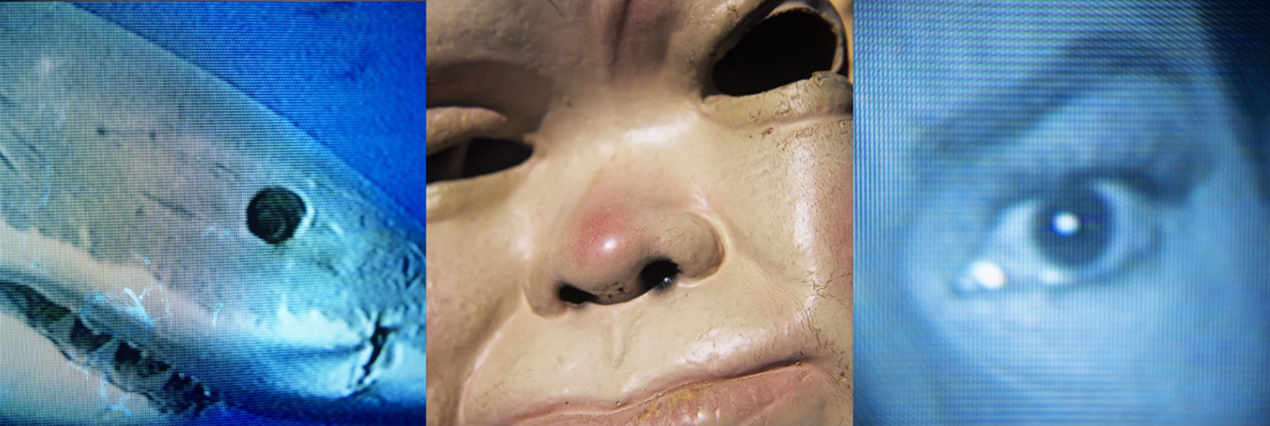

This conversation has been translated from Portuguese. The images in this article are taken from Rio Branco’s films, ‘Maldicidade J’, ‘Wishful Thinking’, and ‘Entre os Olhos, O deserto’. You can watch Rio Branco’s films on Vimeo here.

Yessica Klein: Why do you think that people have repeatedly tried to find a connection between the different platforms you work on — whether photography, painting, or cinema …? That seems almost like a trap to me.

Miguel Rio Branco: What do you mean, working in this way is a trap? It’s not a trap, it is like cooking — you cook with many, many ingredients. Obviously, you have projects that you develop more than others, depending on the moment. But it turns out that they all relate to — and help — each other.

Having a multitude of approaches also helps one not to fall into repetitive formalisms. The editing part is key — as editing ends up being the essence for me, putting pieces together — and that can be done with photography, with film sequences, physical objects, projections, collages, or paintings. I work with rocks and trees — lately I do, anyway. I don’t see any of this variety as ’a trap’. I suppose, a consequence of this varied approach might be that your work is rarely truly recognized…

The works that are best-known are almost all linear: You do something and repeat it… It ends up being style, you end up becoming a stylist. The viewer then only recognizes the style. As I started in photography and cinema after painting, these three approaches are always integrated, for me. And the cinematography, for example, depends a lot on each project, each film.

I learned that photography alone could be enough, but that it was not as much as I wanted. The presence of cinema and painting are much stronger than photography. Photography is a piece of the puzzle, right? The piece you have to know how to use — you need to know how to frame a subject, how to use light. It’s the complete set, for me, that works in a more interesting way.

In my book Entre Os Olhos, O Deserto, I made work incorporating images of rust, iron scraps, wall textures. To that, I brought the influence of painting, sculpture, and installation artwork, along with film. The Daros Collection’s curator said no to showing that work in full. He liked something neater, and showed only my triptychs of photographs. But he is Swiss-German, after all! And so — he has a piece of the work, but from that one doesn’t see the layers that can be created within the work itself.

"Having a multitude of approaches also helps one not to fall into repetitive formalisms."

- Miguel Rio Branco

Do you think that a tendency to read a specialism in a particular medium is the result of the anxiety of critics and viewers who are trying to define you: you are a painter, you are a photographer, you are a filmmaker …?

Yes, that can sometimes be their mistake. If you look at art history, you have a lot of artists who have done work in various areas. The real artists — in the Surrealist movement, for example — worked with cinema, and with photography, sculpture, painting, drawing, engraving. My work became known via photography and it was misread as documentary work because I was connected to Magnum. As a result, people started to see the work in a totally fragmented way. They were seeing a sub-form of it, I would say.

In the ‘70s and ‘80s, making a living from photography was almost impossible. What ended up being known was my published work. My body of work Pelourinho (1979), which was first published by Aperture, ended up influencing other American photographers, who ended up being better-known than me. I am 74 and only now is my work beginning to be better understood. The photography was respected, maybe the cinema part too, but never was the complicity of the work and the broader view of it really understood.

The works of mine that are most in demand are the more lyrical projects. Projects running from the beginning of the ‘90s and continuing today, using the square format image, which I find to be much more pictorial and also more symbolic: the photograph becomes directly involved with the human being. For instance, a series I did at a boxing academy (Santa Rosa Boxing Academy, 1990s): one of my most popular, wasn’t about boxing, it was about the body, it was about the passage of time. Such images are about the marks the human being leaves in society, more than the human being themselves.

Do you still shoot square format, on a Rolleiflex?

At the moment, I photograph almost nothing. I use only my mobile. I’m looking more at architectural constructions and spaces. I’m trying to get back to painting. And obviously, there are the book projects. My job nowadays is much more involved with my archive than actually going out. The last field project I did was in Tokyo in 2008.

And how do you find that process — going back and contemplating all the past work — with a completely different mind, with all the self-knowledge and awareness?

It’s very boring. I take up maybe ten percent of my time editing. The rest of the time I am working on other more engaging things: I have an ongoing ‘labyrinth’ project I am building in my home…

Architecture and the interaction of my work with space started to become more important to me around a retrospective I had at Pinacoteca de São Paulo in 2014, called Teoria da Cor. There, the individual images and objects were placed together in an installation, and you could manage the way people moved around the work.

In 2016 I showed a part of the labyrinthine installation, taking it inside the Museum of Modern Art, into a 100-square-meter space — inserting stones, trees and old televisions. The project is called Wishful Thinking: it considers our wait for nature to take over the world, stopping us screwing with nature and the globe itself.

The day before yesterday I saw the David Attenborough film — it starts with Chernobyl, where nature and wild animals are taking over. These are the times we are living in, with this pandemic, many people are leaving the city… Human beings can always surprise one, though generally for the worse.

"Human beings can always surprise one, though generally for the worse."

- Miguel Rio Branco

When do you think human beings started to fail?

I think they have always failed. There is a part of the human being that will always be shit. There is no way around it. Unfortunately, despite all the information that is coming through these myriad channels that we are using today, most of it is being used to screw people over, not to illuminate or clarify things. I still think that only a minority takes advantage of today’s technological and communications advances in a positive way.

Do you think the artist is still relevant today? Does creating art still have a purpose?

Yes — but not as a trade. Take a filmmaker, like Elia Kazan, who made art exploring relevant social issues; that work had purpose. If you care about an issue personally, and that then becomes more universal or relates to broader social issues, you can create purposeful art with context. Or, it can work even without context, take a Matisse — this sort of work is relevant simply because it elevates people.

You have areas of culture like music that are even more incredible, because they are much more directly emotional than any other area of creation. But often with the visual arts, you find work that is exclusively based on drawings, or small concepts, and that aesthetically does not have a connection to the idea. You have to have a relationship between aesthetics and idea, you cannot have aesthetics alone. Photography, for example, has become so stupid… It makes you want to leave it behind.

Art always has something to do with the ego. But there are some people who have an ego and no shit to offer except that ego. If you have nothing, you have nothing. But art is always relevant, from the moment that it is honest. That sort of work is not made through powerful galleries that started to ‘invent’ artists just to have material to sell.

"If you care about an issue personally, and that then becomes more universal or relates to broader social issues, you can create purposeful art with context."

- Miguel Rio Branco

So the problem with art is consumption?

It is the consumption of the most privileged classes who want to buy, most of the time, to have something to talk about.

The lack of content can be seen most clearly in cinema, in the visual arts, and on television. And television — audiovisual media — this can be used to educate a population in an incredible way.

A lot of contemporary art has become a kind of snotty documentary. It’s complicated, and it’s very annoying. Often it lacks elevation — in art, you have to have a spiritual issue in between creator and content, a poetic issue as well. Art is not documentation: it is an interpretation.

But if you don’t have interpretation, if you have ‘art’ which doesn’t pass through the creator’s own chemistry… well, that is not art.

Each has their own way of deciding what is important to put into the world. Whether you judge yourself in relation to a career, or in relation to your feelings, your conscience, your critical point of view, your aesthetic point of view. What is more important? You think about the market, or you just do what you want to think is important.

In your opinion, do the artists you consider to be good artists have anything in common in terms of personality?

They are all different — except those who copy others (laughs). But in general, the artist has integrity in their own being. They find out who they are, what they stand for. Even if you don’t understand who you are, you recognize yourself in what you are doing. And it’s not just something smart or beautiful or ugly…

For instance, there are moments in which I recognize myself much more than others. There are moments when I have a lyrical element to my work that is very strong and other times where that critical or negative part is very strong. This duality exists in me — otherwise, I would have shot myself in the head. I have a pessimistic side, but I have an optimistic side in relation to humanity too.

You have to have balance. I have projects that are very harsh, and I have ones like Entre Os Olhos O Deserto, which was made at a time when I was feeling much more lyrical, more positive, with two young daughters. You start to see that it is no use being exclusively critical because nobody can take it. Take, for example, the war photographer who only photographs war, war, and more war… Why are they doing it? Adrenaline? The risk? On the other hand, take Ricardo [García Vilanova] he documents war with this, ‘I kind of want to show it, but it is so horrible that I am not able to show it in a raw way’, sort of approach. With that work you already have some personality, something more to it than just negativity.

I believe there is always a positive side, although at the moment, for example, here in Brazil, it is difficult to see at times. Here there is a hecatomb of fires, of stupidity, of crap. It’s been crazy here. And in the art field, I know that artists are terrified because they were relying on government grants and funding, like the Rouanet Law [a Brazilian law which provides monetary funds for use in art and culture]. However, the art market continues to function because there is such a big difference in income — the people who are screwed are the people who have no money. Whoever has money now will continue to have a lot of money.

Do you still consider yourself an outlaw artist?

Not an outlaw artist, I consider myself an outlaw! It started with this story of a diplomat’s son: you don’t belong anywhere and at the same time you belong to many places. But in a way, in art, I am also a bit of an outlaw because my work is not really seen as it should be seen. Although, as I said, people in recent years have started seeing more connections between my works, there are still many who see more the division: “No, your painting doesn’t matter, what matters is your photography!” They continue with this nonsense. But these works are all part of each other.