The Beat Scene: Burt Glinn’s Vivid Portrait of a Subculture

'The Beat Scene' combined Burt Glinn's iconic photos of the Beat Generation with rediscovered and formerly unseen images, building a frenetic, vivid picture of one of America's era-defining artistic subcultures

As part of a season of articles looking at the influence of New York on Magnum’s members, we consider Burt Glinn‘s 1950s work on the city’s outsider art scene, part of the larter Beat movement that would in turn come to be the Beat Generation. Glinn’s book, the beat scene, is available as part of Magnum’s New York Books collection. A select few of Glinn’s images from this period are also included in the newly expanded collection of New York fine prints, which you can see here.

The late 1950s were important years for Magnum photographer Burt Glinn, who joined the agency in 1951, and whose work is the subject of a new collection on the Magnum Shop. Glinn’s work from this time included the desegregation of Little Rock High, Nikita Khrushchev in front of the Lincoln Memorial, Queen Elizabeth II on her visit to New York, as well as profiles of Sammy Davis Jr., Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor and Katherine Hepburn. Glinn was one of few photographers granted access to Fidel Castro’s inner circle, having sped from a New Years party on December 31, 1958, to Havana upon hearing that dictator Fulgencio Batista had fled. His images from that trip are indispensable for understanding this momentous time in Cuba’s history.

Glinn often relied on his own impetus rather than an assignment to pursue a story, a habit he employed to not only capture historical revolutions, but also cultural ones. In the late 1950s, while at home in New York, Glinn began to shadow the American subculture phenomenon known as the Beats. That work, including images both iconic and unseen, is the subject of a new book, the beat scene.

"Key elements of the Beat ethos included the rejection of materialism, the exploration of Eastern and Western religions, spiritual self-discovery, sexual liberation and attention to the human condition "

-

Initiated by a handful of authors (Jack Kerouac, Lucien Carr and Allen Ginsberg among others) seeking to reject narrative norms, the Beats grew to encompass an anti-conformist way of being that redefined post-war American society. Key elements of the Beat ethos included the rejection of materialism, the exploration of Eastern and Western religions, spiritual self-discovery, sexual liberation and attention to the human condition. Many of these values would go on to characterize the hippie movements of the 1960s.

Glinn’s widow, Elena Prohaska remembers speaking to him about his initial compulsion to cover the Beats, also known as the bohemians, or the non-conformists. It began with a conversation with the illustrious editor and journalist Clay Felker, founder of New York Magazine and Glinn’s friend and roommate at the time. “Clay said to Burt, ‘We have to do something with these non-conformists who are all over the place. Go after those guys. Go to openings.’ Burt just did it, and he went to everything. He went to the poetry readings, to the gallery openings, to artists’ studios.”

"He did, indeed, seem to be at everything, traversing the city streets, outside and inside. He was on nondescript street corners at cheap bodegas, in parks, Times Square, upscale gallery openings and downtown loft parties "

-

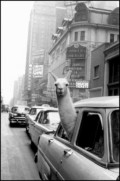

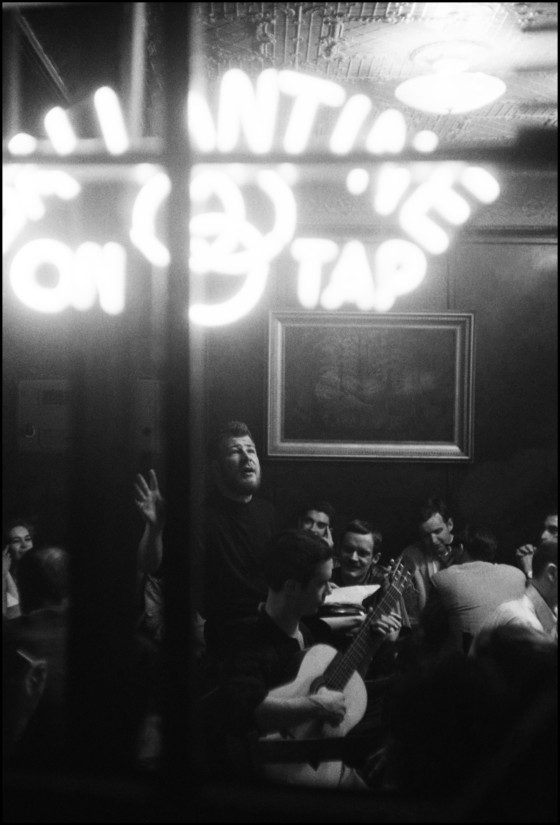

Glinn’s images of the Beat scene suggest that he did, indeed, seem to be at everything, traversing the city streets, outside and inside. He was in parks, Times Square, upscale gallery openings and downtown loft parties. He was in crowded, smoke-filled cafés. He was at Merce Cunningham’s dance recitals, and Willem de Kooning’s studio.

Glinn’s motivation paid off. A selection of these images appeared in a 1957 editorial for Esquire and again in 1959 for Holiday magazine, accompanied by Jack Kerouac’s essay, ‘and this is the beat nightlife of new york.’ In 1960, Holiday sent Glinn to chronicle the Beat scene in San Francisco, a project that entailed Glinn’s most extensive use of color film yet.

This body of work has now been assembled and reproduced, together with Kerouac’s Holiday essay, in the beat scene, published this month by Reel Art Press. An accompanying exhibition, “the beat scene: photographs by burt glinn,” at the Beat Museum in San Francisco opens July 19, and will be followed by “Burt Glinn: photographs of the New York Beat Scene,” opening September 12 at Jason McCoy Gallery in New York.

Many of these images have never been seen before. They were recently discovered, along with Kerouac’s original manuscript, in Burt Glinn’s archive. They had not been touched for over 50 years. Remarkably, over half of the negatives discovered were color.

the beat scene is divided chronologically into three parts: upper and lower bohemians, east coast beats, and west coast beats. The majority of images were taken in New York. This is also the landscape of Kerouac’s essay, in which he paints the scenes of an average Beat night with the catchy rhythm so typical of his style, one that is mirrored in Glinn’s images:

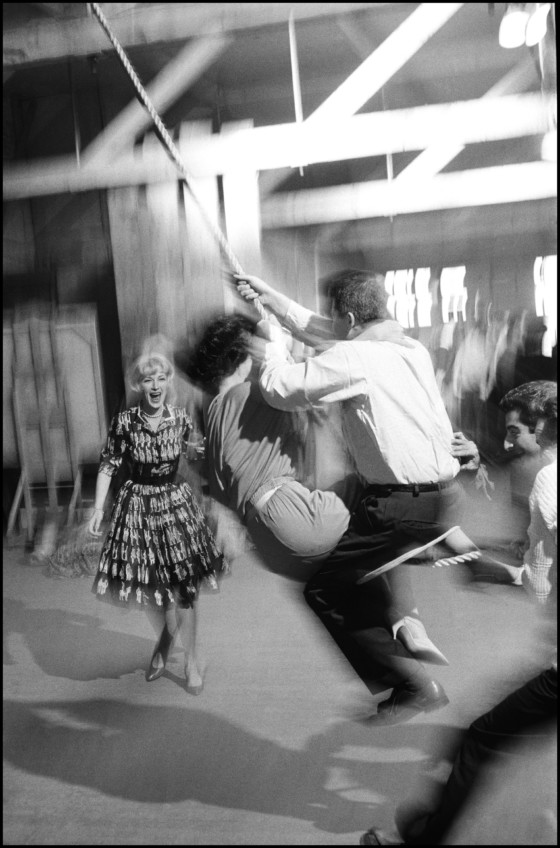

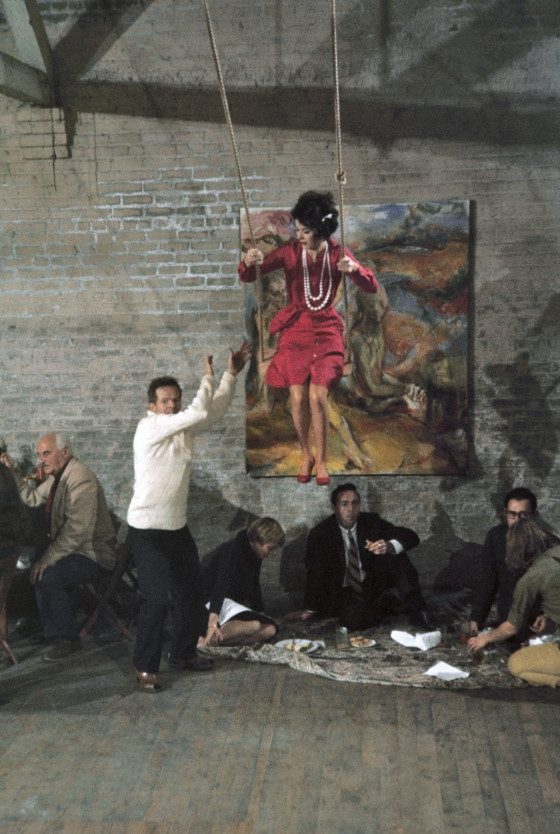

There’s a big party at some painter’s loft, wild loud flamenco on the phonograph, the girls suddenly become all hips and heels and people try to dance between their flying hair. Men go mad and start tackling people, flying wedges of whole groups hurtle across the room, men grab men around the knees and lift them nine feet from the floor and lose their balance and nobody gets hurt, blonk.

" There is a humanistic thread that ties these images together, along with the palpable energy of life in the city: movement, discourse, change"

-

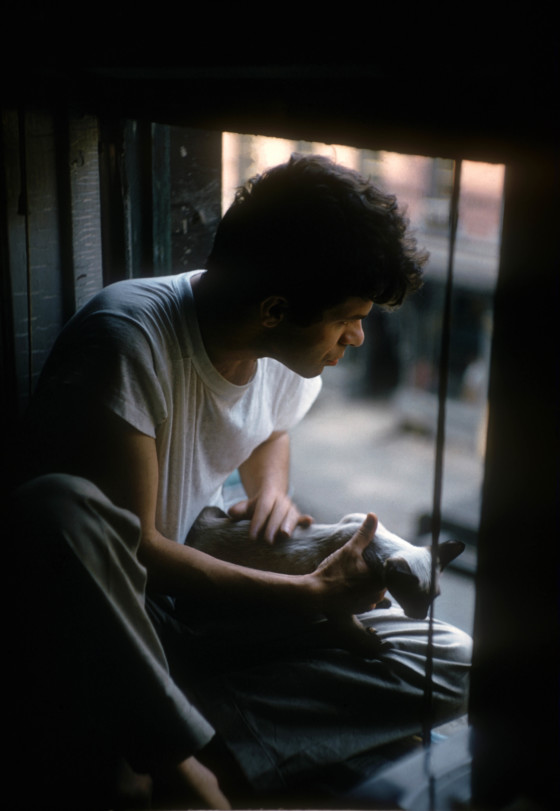

Glinn’s photographs reflect a spontaneity inherent to the Beat philosophy: arms flail, music plays, people talk, eat, dance, paint. They are wrought with emotion and tension, and yet exude a calculated nonchalance. They touch on life in all of its glories and absurdities, and seem to depict not just the Beats, but also the ‘everyday’ man. There is a humanistic thread that ties these images together, along with the palpable energy of life in the city: movement, discourse, change.

They transport the viewer to this lost but pivotal moment in the city’s cultural awakening, enabling one to participate as a bystander on the city streets, in the bar, smelling and feeling the atmosphere, understanding the time. Here are raw, detached glimpses of iconic names–Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsburg, LeRoi Jones in addition to Helen Frankenthaler, Anita Huffington, Franz Kline, Barnett Newman and others–not idealized but rather laughing, talking, dancing seemingly as-they-were. They are names that spanned artistic mediums, challenged norms and invented a new way of being.

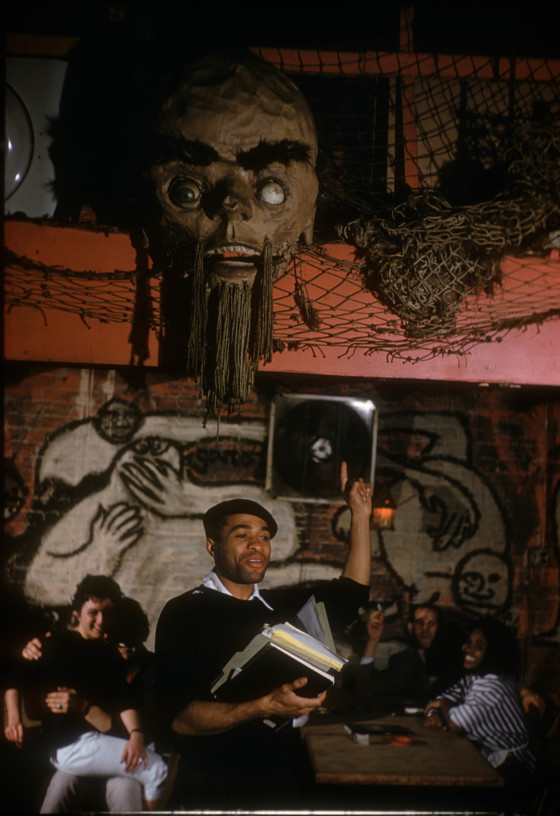

Gregory Corso reads at the Seven Arts Coffee Gallery in Times Square, and later mingles with women, exchanging a sneaker with one Beatnik admirer. Ted Joans reads his poetry at the Bizarre, a coffee shop in Greenwich Village. “Joans is the only Beat with a sense of humor about the Beats,” Glinn writes.

All of the image captions are Glinn’s own. Illuminating, astute and often wry, they reveal his concern with rendering his subjects honestly, as well as an evident perception of the Beat’s enduring legacy.

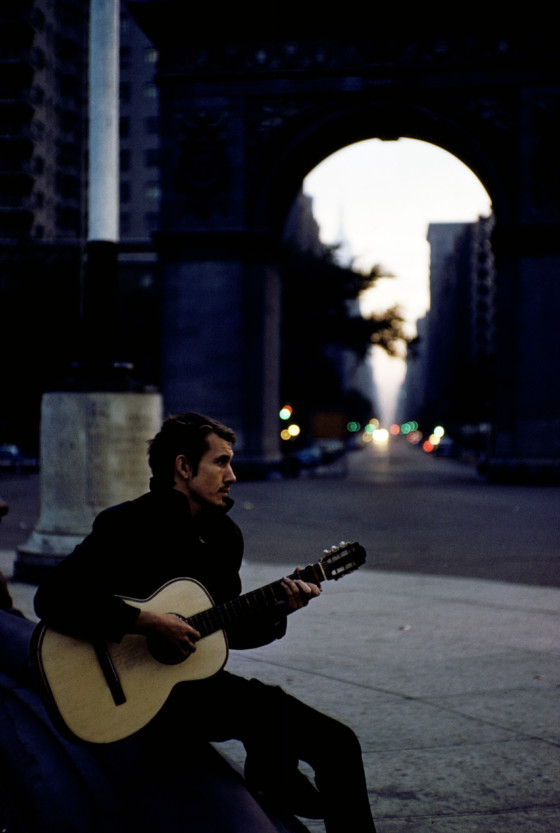

“A streak of loneliness runs through these gaudy evenings on the town. Tonight, a lone guitarist plays the last music of the night,” Glinn writes of a musician he encountered near dawn at Washington Square Park.

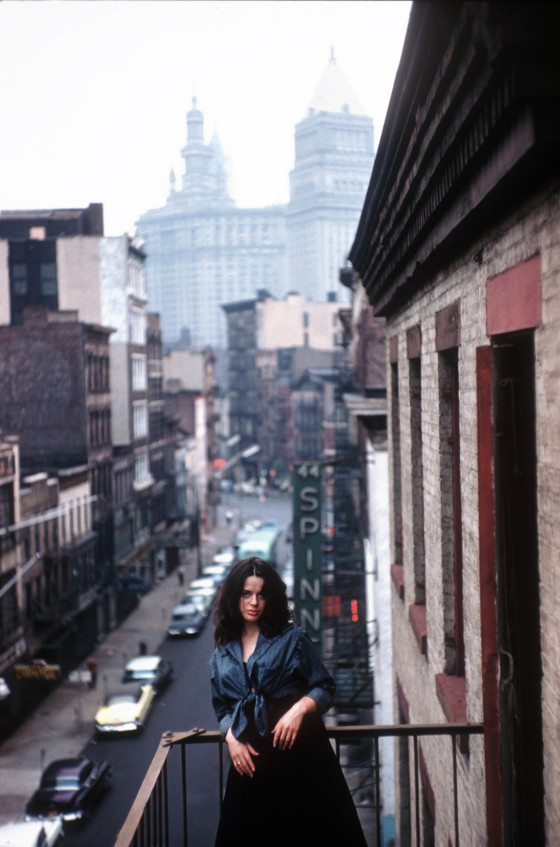

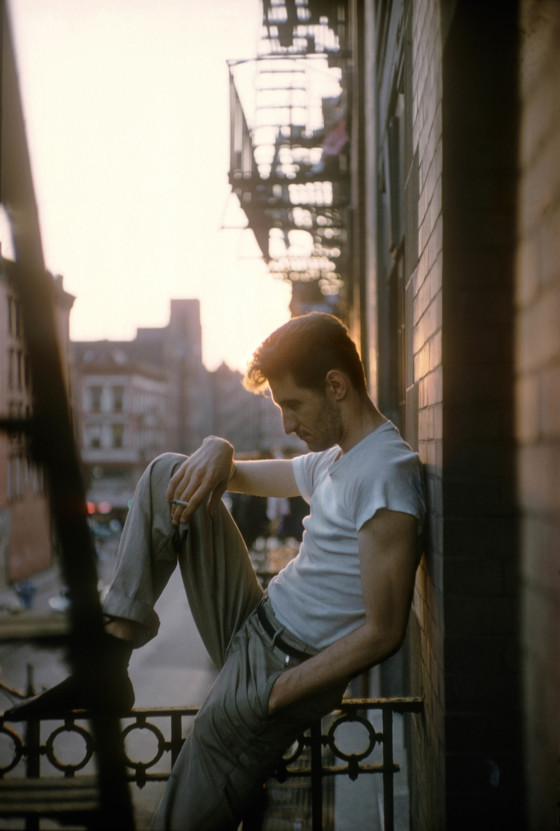

“Ray Bremser on the fire escape of Allen Ginsberg’s apartment in the East Village. Bremser is a Beatnik jazz poet and probably describes himself as an ex-convict.”

In a series of four images, spread across two pages, Glinn captures a drunken argument between Gregory Corso and a New York Post reporter, in which Corso screams, “But you don’t understand Kangaroonian weep! Forsake thy trade! Flee to the Enchenedian Islands!”

Later, Glinn’s portrayal of the Beats in San Francisco reveals his keen eye for color and composition, exemplified in his abstract shot of Earl Bostic and his trumpet player at the city’s Black Hawk nightclub. “For the beats, jazz is almost food and drink,” Glinn writes. Also in San Francisco, he shoots a wild party given by the eminent record-cover artist David Stone Martin, with revelers on swings, and musicians in fezzes playing bongos and exotic instruments. He captures Lawrence Ferlinghetti in his City Lights bookshop, and a performance of Michael McClure’s “The Feast.”

“Burt blended in very well,” Prohaska remarks. “He gave the same dignity to the poets and the painters as he did to the capitalists.”