In the Studio: Constantin Brancusi’s Paris Home

Wayne Miller’s photographs capture the aesthetic contrasts of the elusive sculptor’s life

In the Studio is a series dedicated to the photographic documentation of artists within their workspaces. Over more than seven decades Magnum’s member-photographers have captured images of the inner sanctums of many artists, often forging long-standing working or creative partnerships with them in the process. The images made in the studios of artists, in the company of their creatively imposing occupiers, reveal everything from insights on techniques and fabrication processes to illuminating clutter, reassuringly normal mess, and hints at the personal lives of individuals beyond their well-known artistic output.

You can see other stories from the In the Studio series, here.

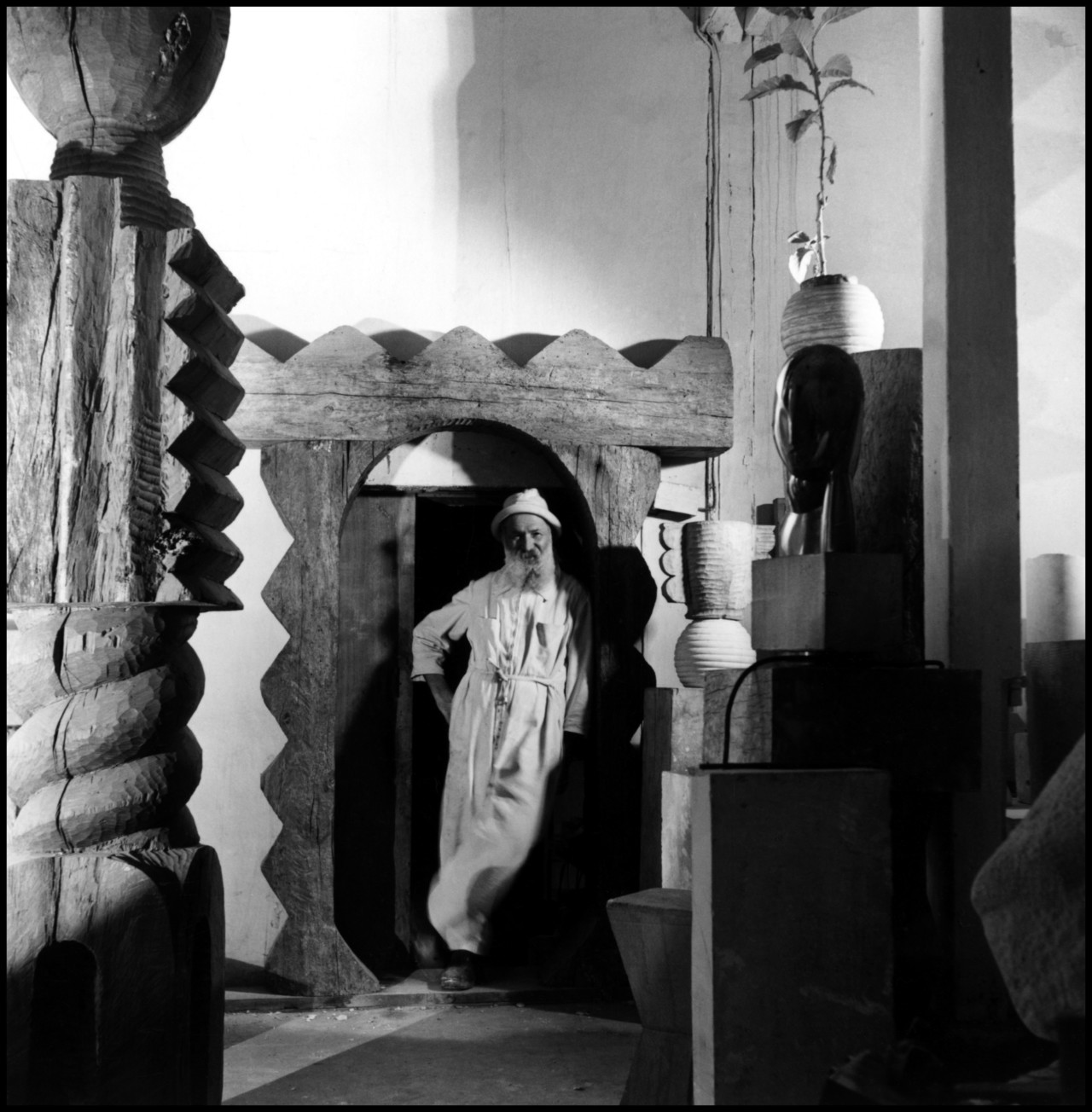

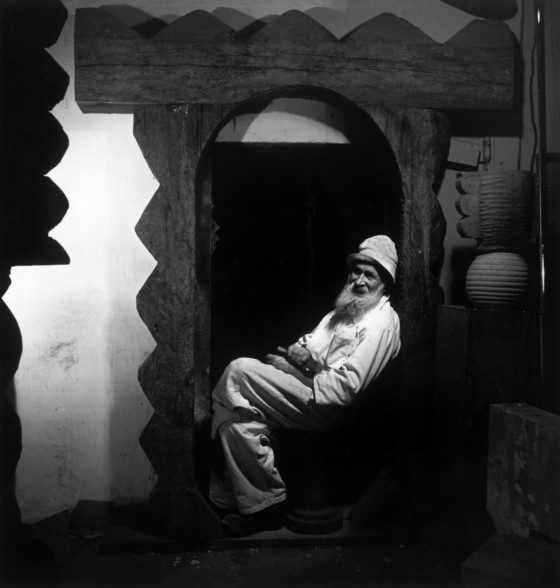

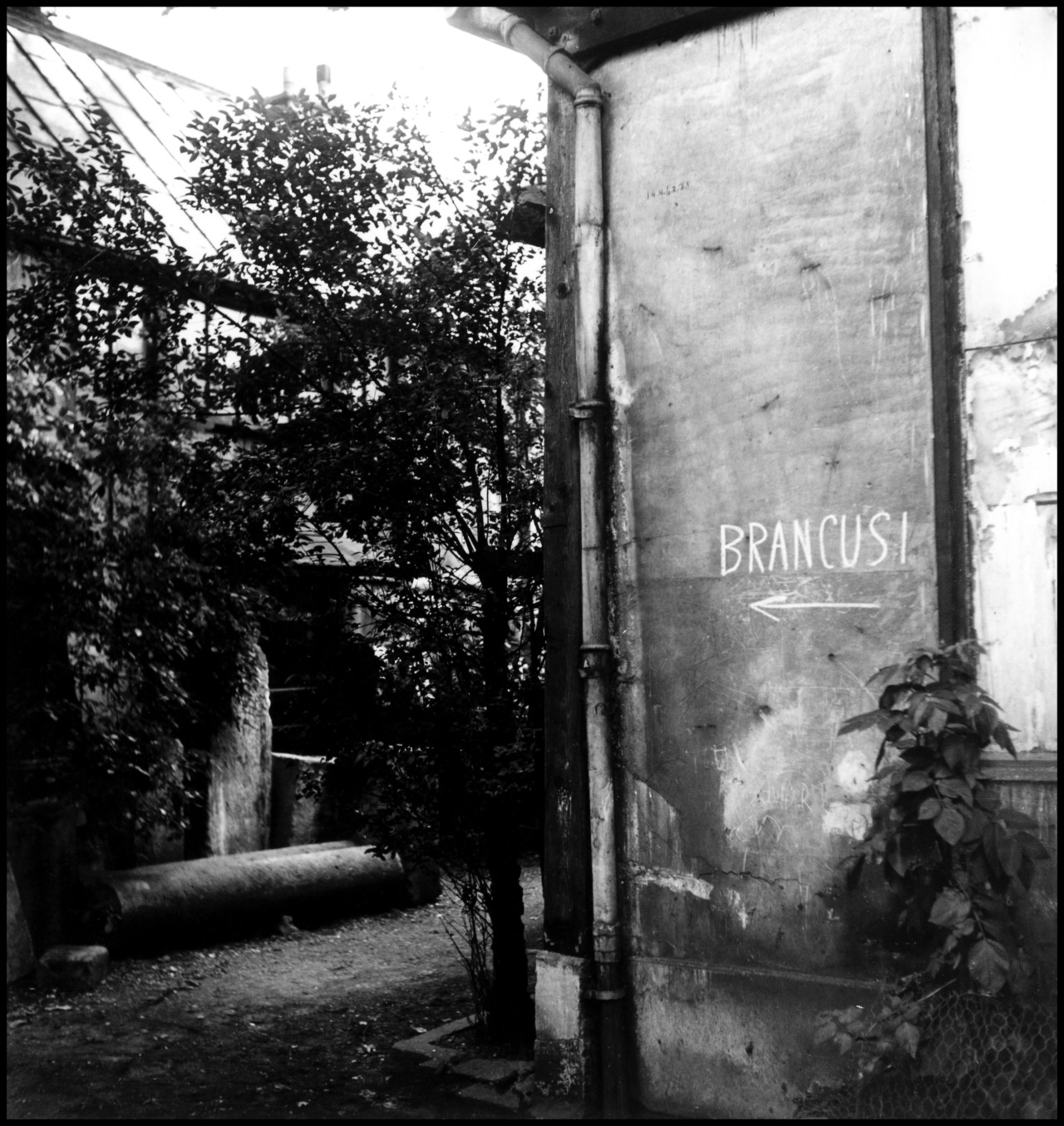

Constantin Brancusi arrived in Paris from Hobita, in southwestern Romania, in 1904. While the idea of such a relocation might not have been surprising for a graduate of Bucharest’s School of Fine Arts, intent on continuing his work at the turn of the century, his mode of travel was more out-of-the-ordinary: he walked to the French capital. This pilgrim-like, almost ascetic approach to his moving home marked out an attitude that the sculptor would continue to employ throughout his life and work: becoming arguably the most famous modernist sculptor in the world while refusing the trappings of success or wealth, living alone, and dressing in utilitarian overalls and peasant clothing. Wayne Miller’s 1946 photographs of the often elusive sculptor embody the aesthetic juxtapositions of Brancusi’s working and living spaces, and capture the contrasts between his life, processes, and artworks.

Shortly after his arrival in Paris, Brancusi found himself in contact with Auguste Rodin, who was at the height of his career. Rodin offered Brancusi a role as an apprentice in his studio – an offer he rejected, according to some. It seems that what might, to most aspiring sculptors freshly-arrived in Paris, have seemed a dream position, was, to Brancusi, an odd fit. Rodin’s approach to sculpture, while progressive and modern by most standards of the time, was far removed from Brancusi’s view of what the artform might achieve if pursued – or perhaps reduced – to its most essential qualities.

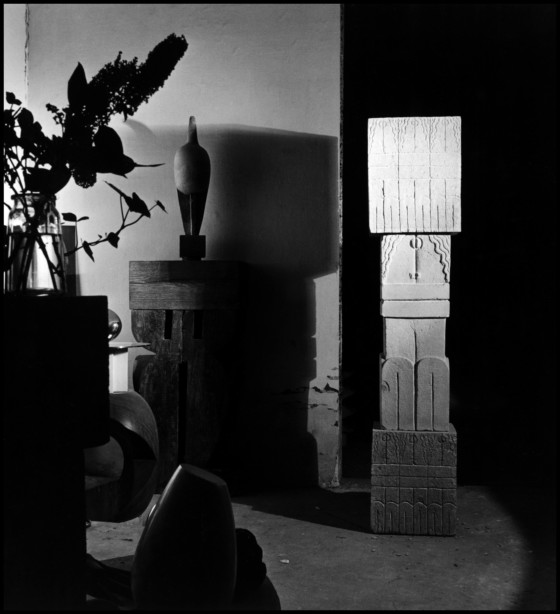

As Brancusi put it, “What is real is not the external form, but the essence of things.” Sculpture that concerned itself with details, realism, or with an attempt to look like what it was meant to represent, was to Brancusi’s mind rather missing the point. By focusing upon what made a bird a bird, or made a fish a fish, he hoped to create minimal forms that conveyed the movements and true nature of his subjects rather than static facsimiles of them. The divergence between Rodin and Brancusi’s approaches to sculptural depiction can be neatly observed in their respective works, both titled The Kiss.

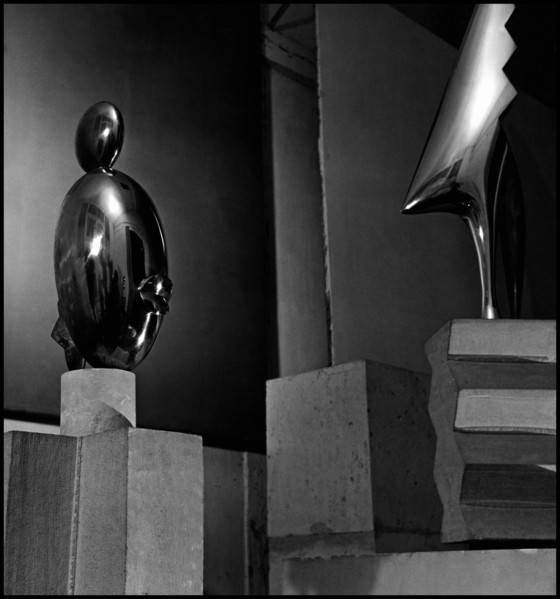

Brancusi’s approach to sculpture famously led to one of his best-known works being impounded by customs agents in New York City. Bird in Space – a polished bronze totem, elongated and tapering upward, captures more the notion of flight as an act or feeling, than it does represent a bird in its shape, details or finish. While typical of Brancusi’s radical approach, unfortunately the work did not meet the US customs service’s definitions of sculpture, which required – somewhat narrowly – that any such work hoping to enter the country free from import tax be “reproductions by carving or casting, [and] imitations of natural objects.” Indeed, the sculpture was initially classified as a utilitarian object rather than a work of art, placing it alongside medical and culinary utensils and awaiting a hefty tax levee. Brancusi challenged the decision in court, and eventually the judge, J. Waite, agreed that the definition of art which Bird in Space had failed to meet was outdated.

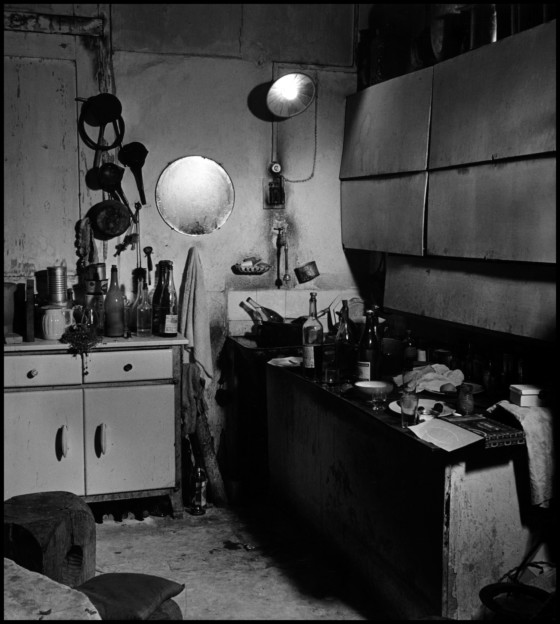

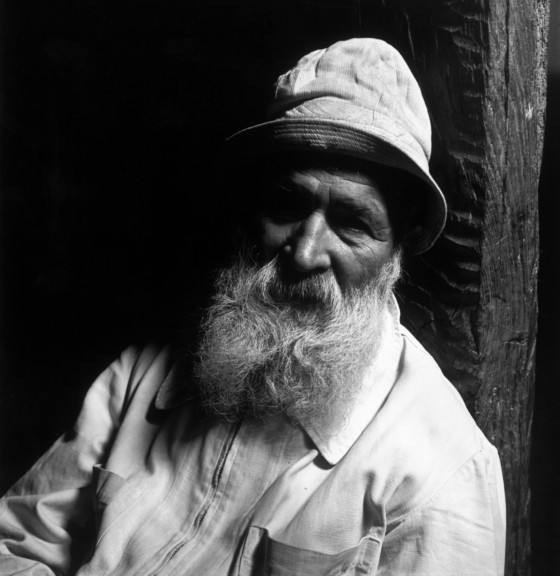

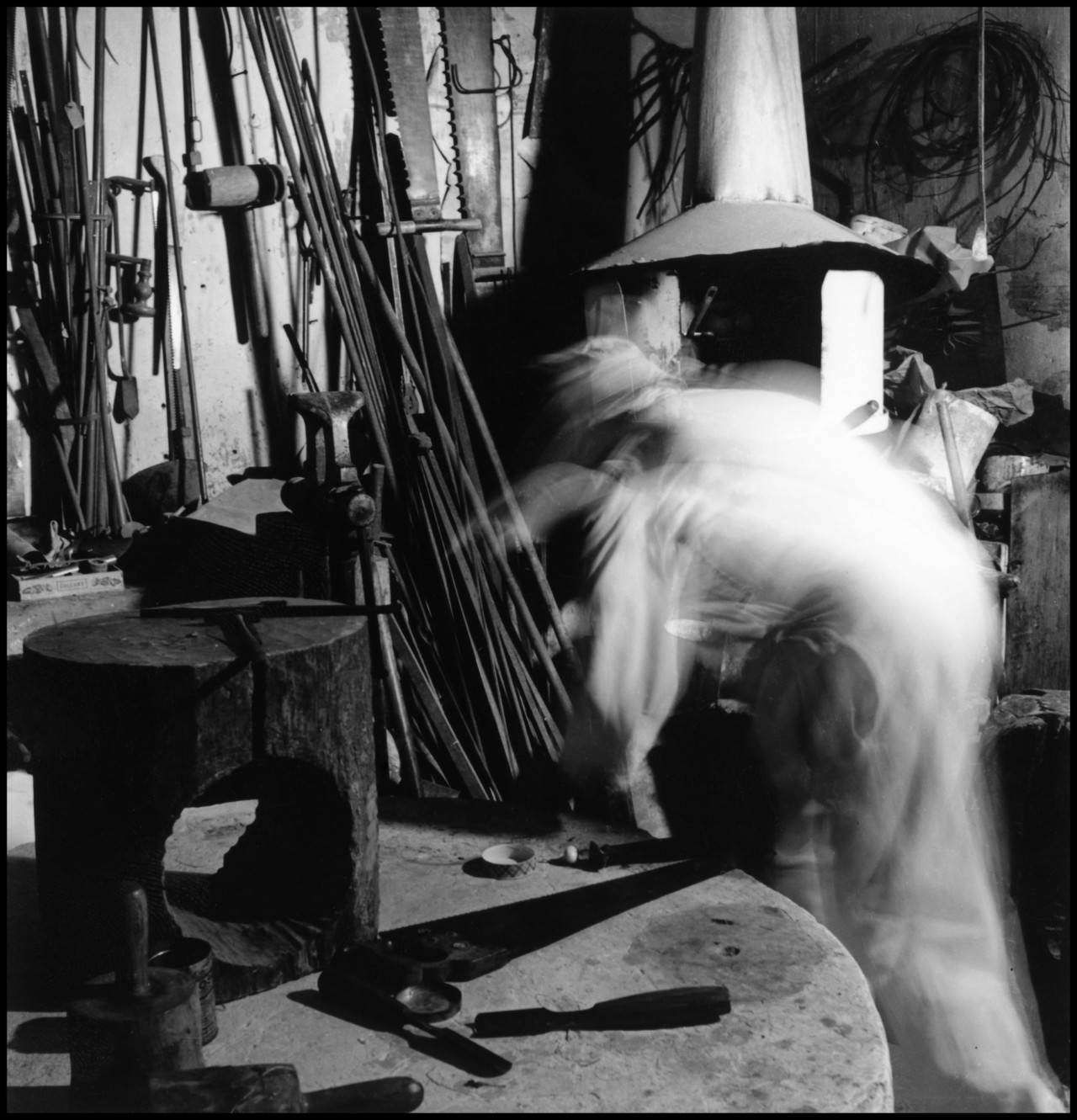

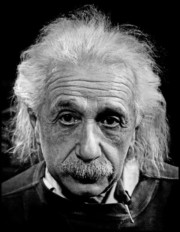

Wayne Miller’s photographs, made in the sculptor’s Paris home and studio, capture both the art and the artist. By 1946 the thick black beard that the artist had maintained in his youth had grayed, but his ultra-practical overalls, canvas hat, and somewhat unkempt appearance echo early descriptions of the man, whom Peggy Guggenheim once described as “half astute peasant and half real god.” Miller’s images also capture the jolting juxtaposition between Brancusi’s somewhat disheveled person, his cluttered – almost medieval-looking – workspaces, and the beautiful elegance and simplicity of their products elegantly arranged on simple pedestals around his home. Stark shadows falling over highly polished brass, smoothed stone, and coarse wooden blocks contrast with a striated hammer and with the sculptor’s own smiling, weathered appearance.