Giacometti in His Studio

The late artist and his original atelier through the lenses of Magnum photographers

Magnum Photographers

In the Studio is a series dedicated to the photographic documentation of artists within their workspaces. Over more than seven decades Magnum’s member-photographers have captured images of the inner sanctums of many artists, often forging long-standing working or creative partnerships with them in the process. The images made in the studios of artists, in the company of their creatively imposing occupiers, reveal everything from insights on techniques and fabrication processes to illuminating clutter, reassuringly normal mess, and hints at the personal lives of individuals beyond their well-known artistic output.

You can see other stories from the In the Studio series, here.

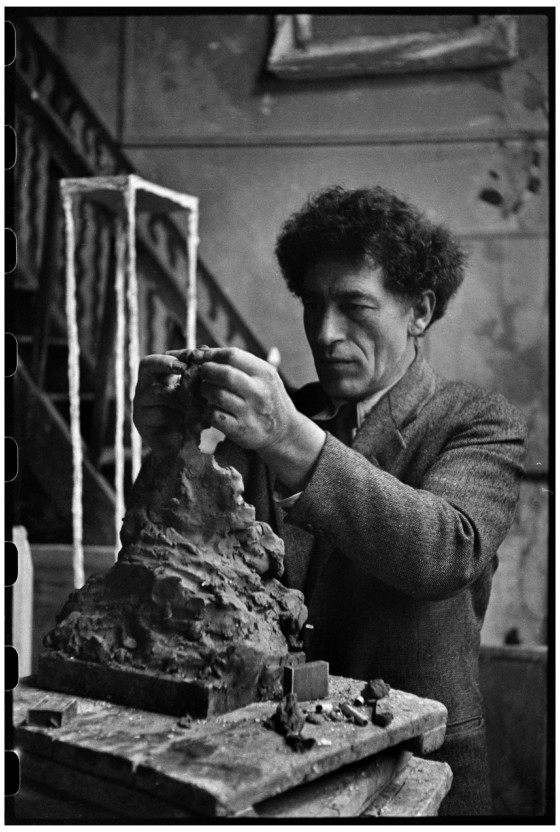

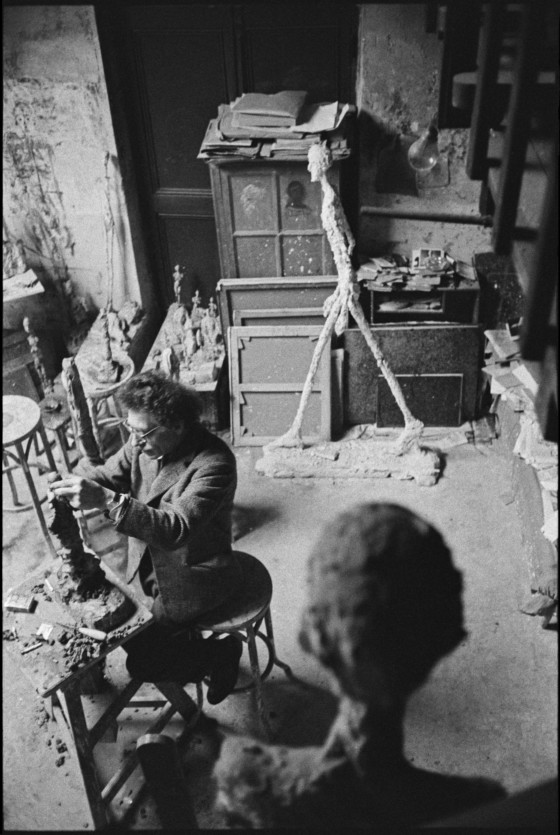

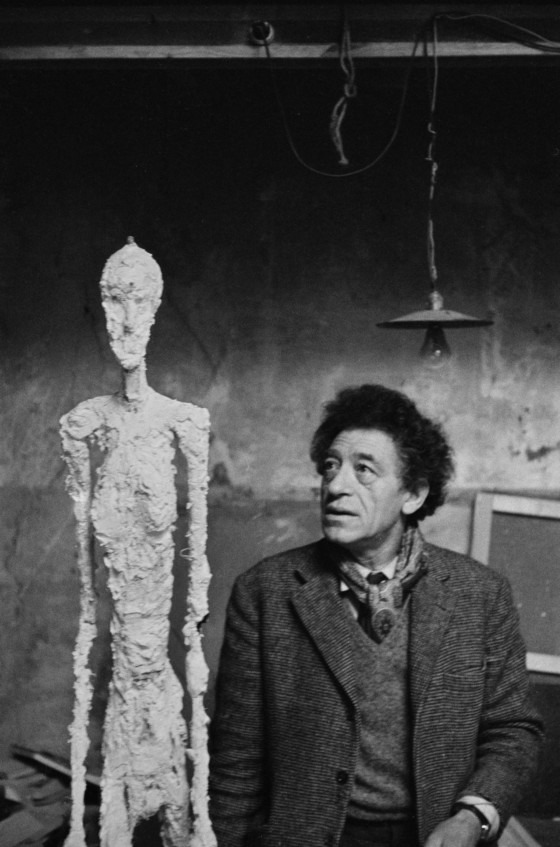

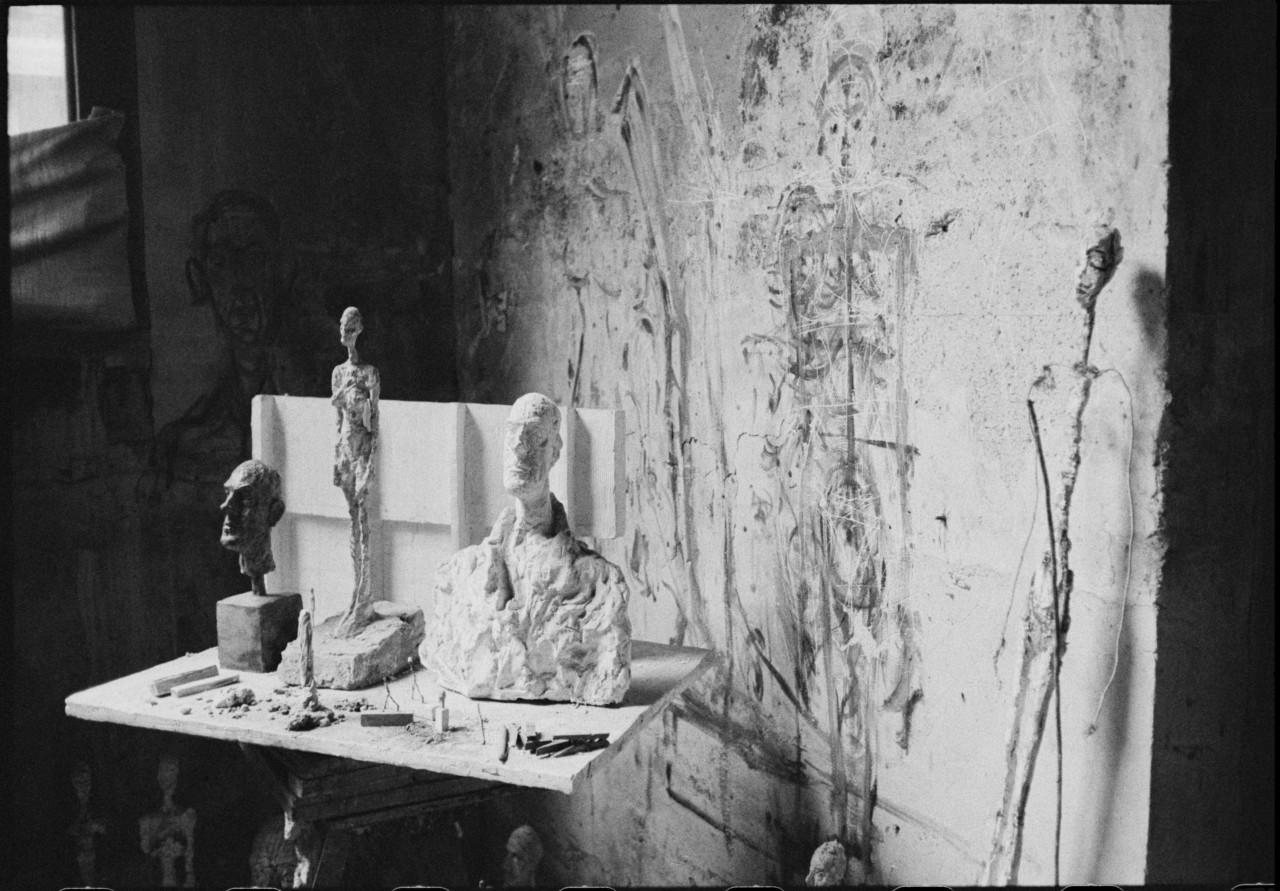

In the winter of 1926, Swiss sculptor and painter Alberto Giacometti moved to his studio at 46 Rue Hippolyte-Maindron in Montparnasse, Paris. The celebrated Swiss artist would spend the next forty years ensconced in his dilapidated studio, with its higgledy-piggledy shambolism and plaster-flecked walls, affectionately naming it the ‘cave’. Open to friends and the odd stranger, the studio, over time, acquired legendary status.

On June 21, the Giacometti Institute will open its new premises in the sculptor’s old district, Montparnasse. As the artist’s original property was renovated, the launch will showcase a painstaking reconstruction of Giacometti’s studio as it was found after his death in 1966. This feat was made possible by the hundreds of photographs documenting Giacometti working in his ‘cave’, a large portion of which were taken by Inge Morath, René Burri and Henri Cartier-Bresson.

"The longer I stayed, the bigger it became"

- Alberto Giacometti

The studio’s twenty-three square meters were often described as claustrophobic, but even when fame and fortune came knocking, Giacometti would not leave 46 Rue Hippolyte-Maindron. Recalling the space, he once wrote, “It’s funny when I took this studio … I thought it was tiny … But the longer I stayed, the bigger it became. I could fit anything I wanted into it.”

With a leaky roof, cement floor, and dim lighting, it offered the right environment for Giacometti to pursue his relentless cycles of creation and destruction. As John Berger chronicled in his essay on the sculptor, Giacometti was once asked where his works would go if they left the studio. He replied, “bury them in the earth, like that they may be a bridge between the living and the dead.” These ideas of decay and impermanence, which Giacometti connected to the horrors of the Holocaust and his post-war Existentialist beliefs, were manifested in the crumbling flesh of his bronze figures, such as Walking Man I.

"Bury them in the earth, like that they may be a bridge between the living and the dead"

- Alberto Giacometti

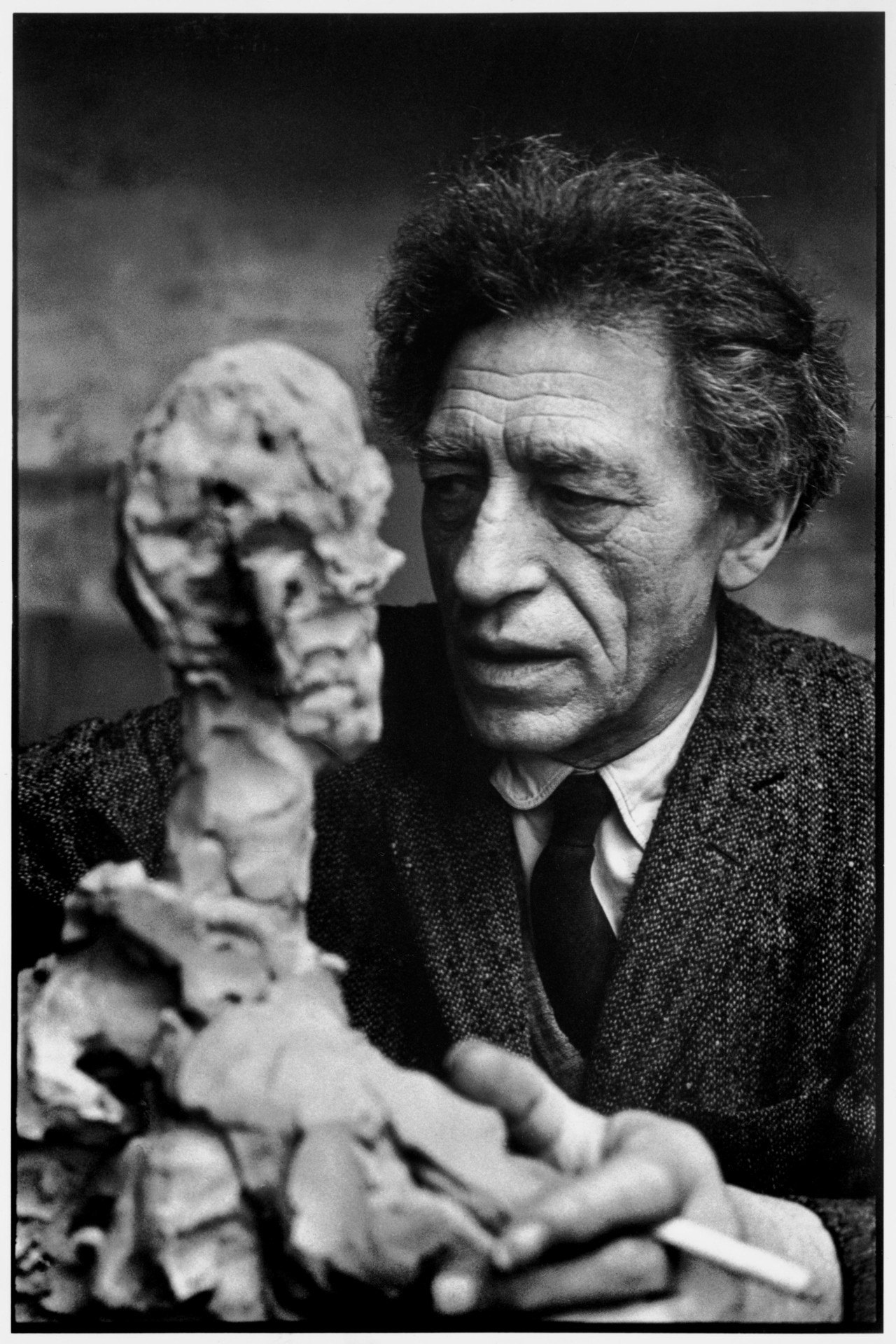

Magnum co-founder Henri Cartier-Bresson first met Giacometti in 1938. The photographer, a passionate draughtsman himself, had stopped by 46 Rue Hippolyte-Maindron in pure curiosity. This initial meeting formed the bedrock of a 25-year friendship, in which the pair realized their inherent creative similarities. As Cartier-Bresson described, “We are playing with things that disappear… we’re struggling with fleeting moments where relationships are in flux.”

The photographer also caught something of the creative dialogue at work. Giacometti used to say his sculptures had the “mystery of those faces and of the life reflected in them”, as Cartier-Bresson’s portrait of the sculptor considering his work suggests. The photographer almost saw Giacometti as one of his sculptures, writing, “His face looks like a sculpture that would not be his, except the furrows of wrinkles.”

"We are playing with things that disappear..."

- Henri Cartier-Bresson

Throughout his career, Giacometti welcomed photographers. In the 50s, Inge Morath visited on the instruction of the French art magazine L’Oeil. In art historian Pierre Schneider’s memories of the studio, Morath was busy capturing shots of Giacometti up a ladder when she noticed a gaseous smell leaking from the bedroom of Giacometti’s wife Annette. She quickly raced to open a window. Giacometti, so involved in his work, had barely noticed.

René Burri would also be sent along to the ‘cave’ in 1960, as part of a series on Swiss artists living in Paris for Schweizer Illustrierte. The photographer observed the sculptor for an entire day, even going with the artist as he took breaks in the local coffee shop. For Burri, capturing the surrounding milieu of an artist was paramount, with their respective studios often creating a contextual framework for the photos.’

The photographs of the artist amongst the crammed contents of his, since renovated, Parisian studio offer insight into one of the most important sculptors of the 20th century. They also reveal how the creative mythos is often housed in the studio, and how space can shape an artist’s work.