In the Studio: An Afternoon at Ghost Ranch with Georgia O’Keeffe

Philippe Halsman photographed the painter in her famous home and workspace in 1948

In the Studio is a series dedicated to the photographic documentation of artists within their workspaces. Over more than seven decades Magnum’s member-photographers have captured images of the inner sanctums of many artists, often forging long-standing working or creative partnerships with them in the process. The images made in the studios of artists, in the company of their creatively imposing occupiers, reveal everything from insights on techniques and fabrication processes to illuminating clutter, reassuringly normal mess, and hints at the personal lives of individuals beyond their well-known artistic output.

You can see other stories from the In the Studio series, here.

“In the evening, with the sun at your back, that high sage-covered plain looks like an ocean,” mused Georgia O’Keeffe to the New Yorker writer Calvin Tomkins in the Autumn of 1973, when he visited her at her New Mexico desert home. Taking a drive out into the hills towards the town of Taos, O’Keeffe pointed out of the window, far into the distance, and said, “the color up there – the blue-green of the sage, and the mountains, and the white flowers – is different from anything I’d ever seen. There’s nothing like it in Texas or even in Colorado.”

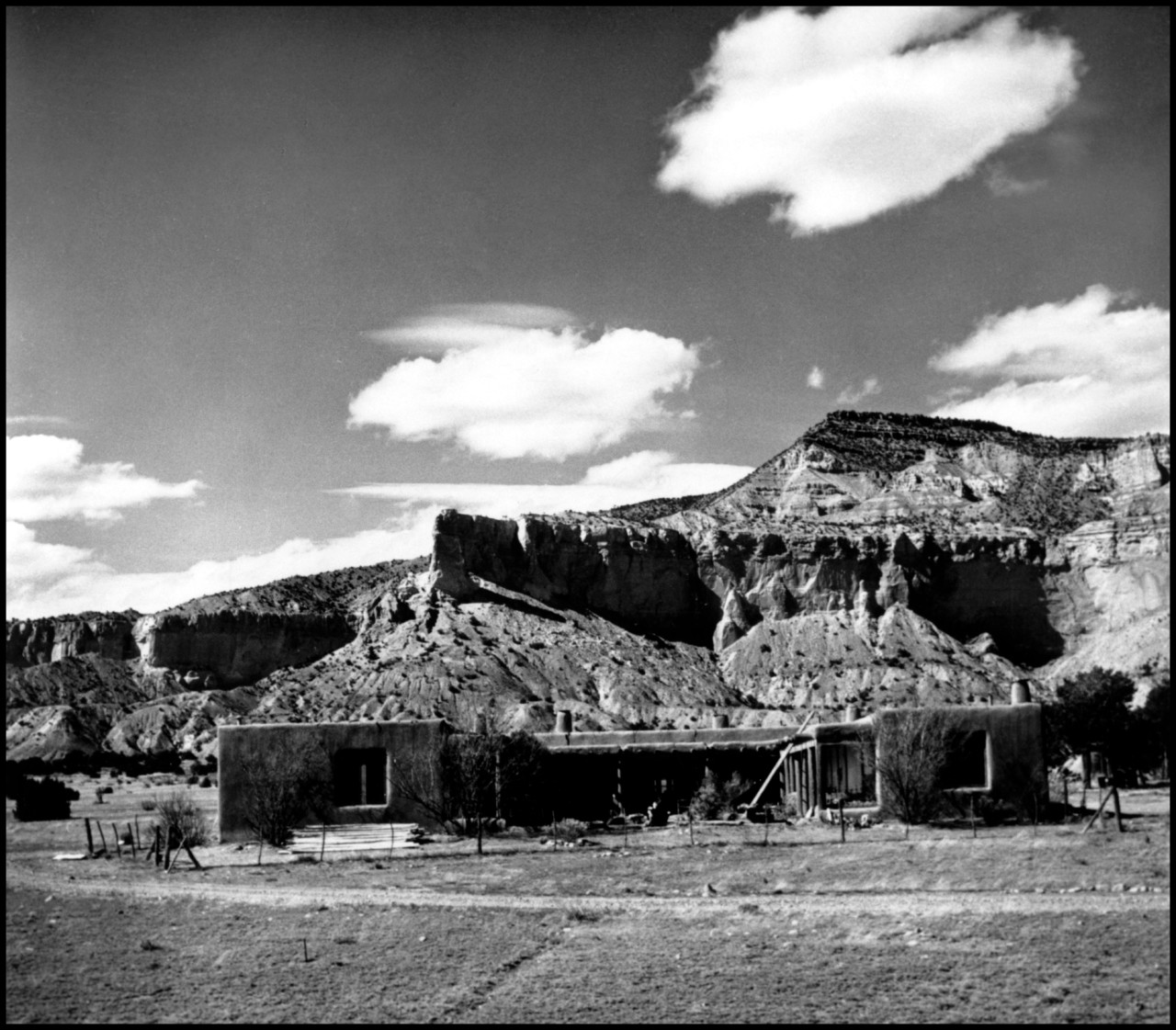

The tawny, arid landscapes of New Mexico are wrapped up in the mythology of Georgia O’Keeffe almost as much as her iconic flower paintings are, with Ghost Ranch – the place at which she spent the better part of four decades of her life – imprinted indelibly onto our collective cultural memory. Each year, thousands of her fans descend upon it, treating the journey as something akin to a pilgrimage (even Calvin Klein once described visiting it as “like a religious experience”).

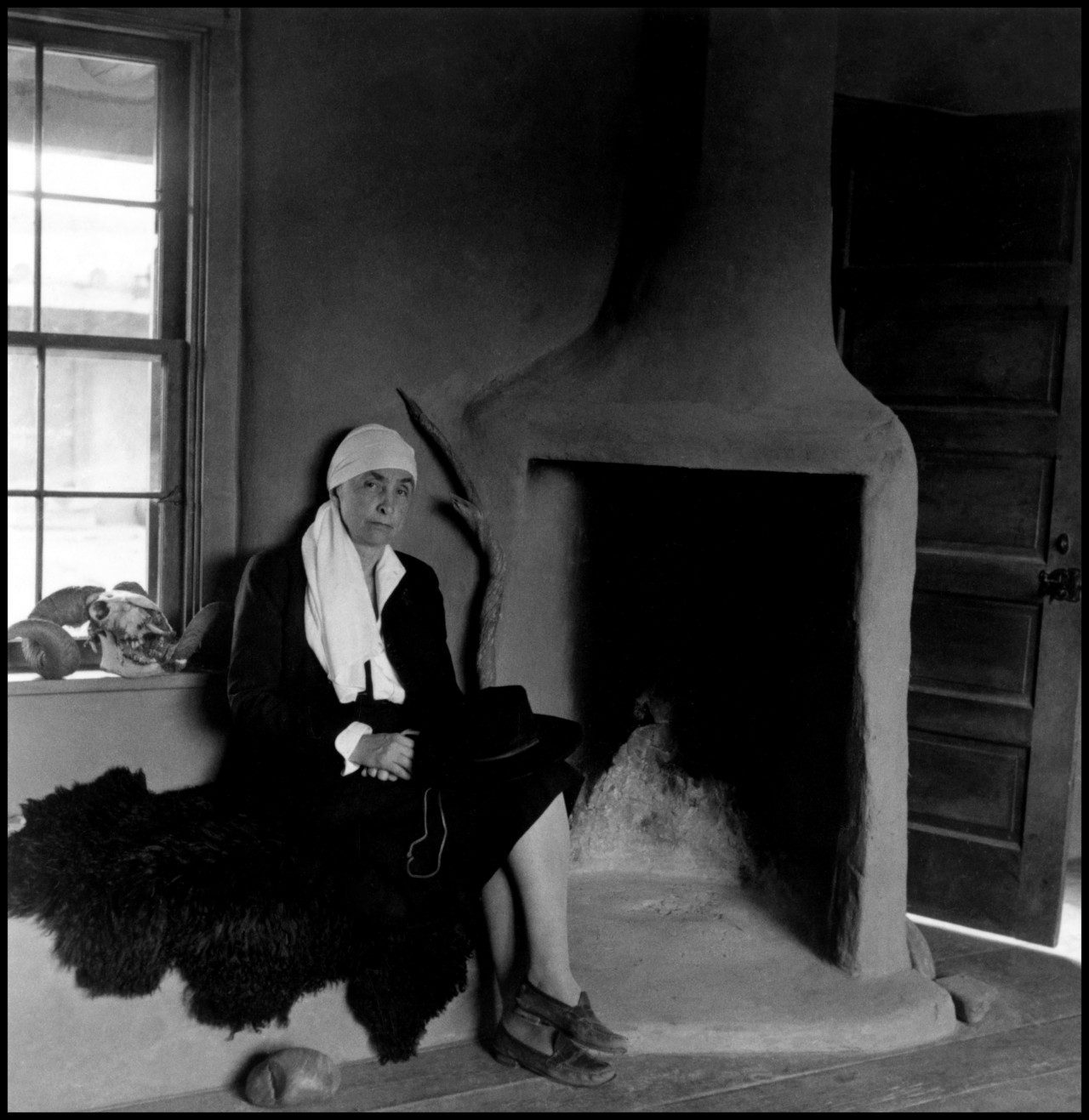

O’Keeffe herself became enamoured with Ghost Ranch after staying for several summers in the 1930s, and in 1940 she finally convinced the owners to sell her a modest adobe house and a small piece of land on the 21,000-acre site. Under O’Keeffe’s ownership the house remained simple and minimally decorated, with just a few small collections of found, usually natural, objects assembled in different spots. O’Keeffe liked the way the walls felt like an extension of the warm earth they rose from. In her studio she whitewashed them, and installed a picture window to make the most of the desert view. Standing before it summer after summer she painted the dusky pink and yellow cliffs that stretched out around her. It’s here that Magnum photographer Philippe Halsman visited her on a quiet afternoon in 1948.

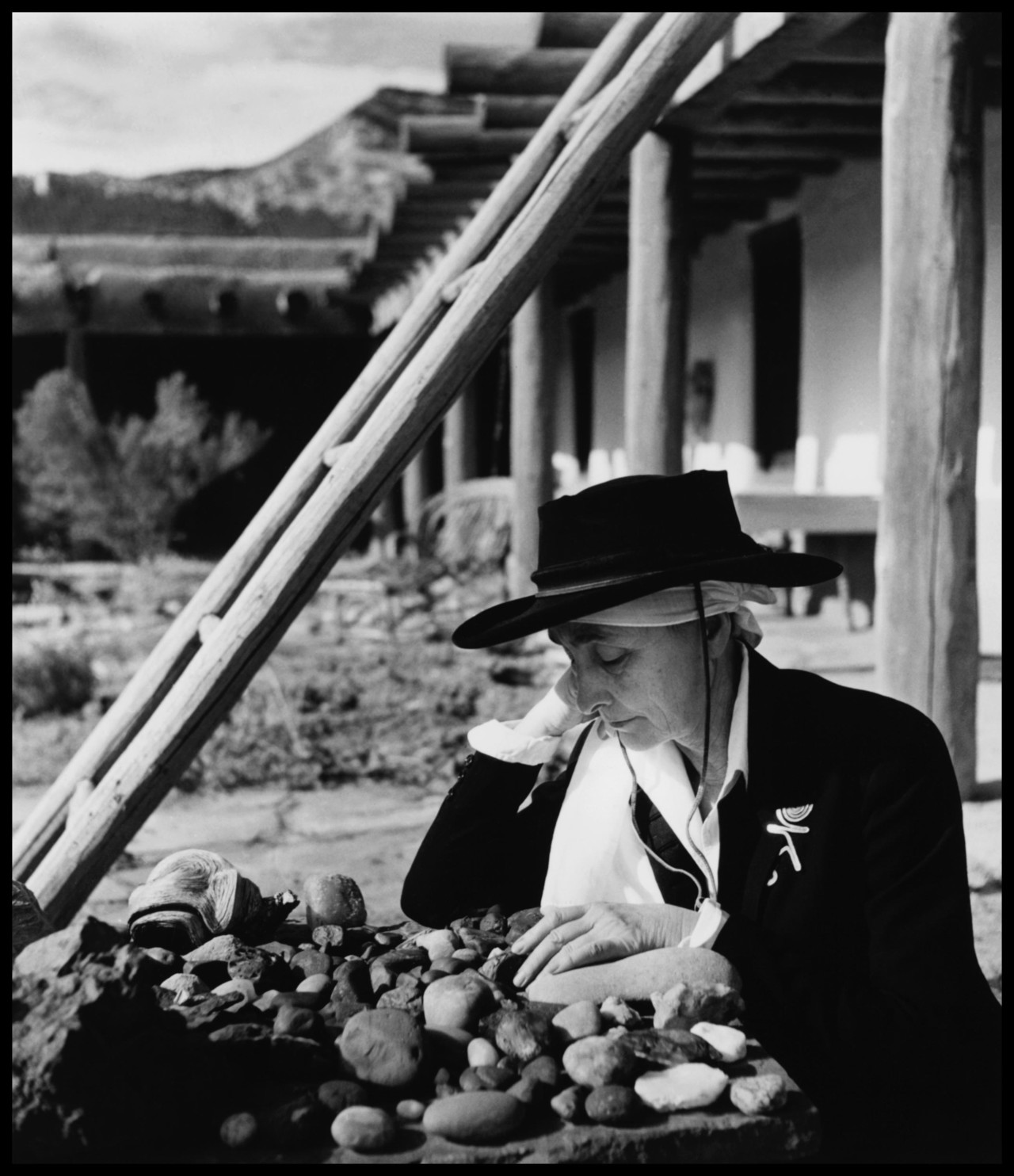

Halsman is perhaps best known for his mid-century celebrity portraits of icons including Albert Einstein and Marilyn Monroe, or for his riotous, surrealist pictures he collaborated on with art-world figures such as Jean Cocteau and Salvador Dali – who appeared frozen in mid air with cats and standing before a skull fashioned out of nude female bodies. Halsman also photographed Alfred Hitchcock as he posed with stuffed birds against exaggerated stormy skies to. The images he made of O’Keeffe, however, are altogether quieter; there is none of that absurdism or theatre, and none of that action. Instead, dressed in her signature all black attire with a long white scarf wrapped about her face, Halsman portrayed O’Keeffe as she went about her day at home.

In almost every one of Halsman’s O’Keeffe pictures, animal skulls are somewhere to be found, lingering at the edges of the frames like spectres of influence for her work. In one black and white image, she sits upon the steps in the courtyard, her small frame hugging a huge cow skull as she looks off into the distance. In another, colour this time, a skull far bigger than her own is mounted on the wall above her. Elsewhere, there is the same garden scene photographed from different angles, the wide brim of O’Keeffe’s vaquero hat casting her face almost entirely in shadow. Tinkering with an assortment of bones and stones, she appears tactile with the things on the table before her here – objects that made their ways into her paintings time and time again as symbols and signifiers of bigger ideas.

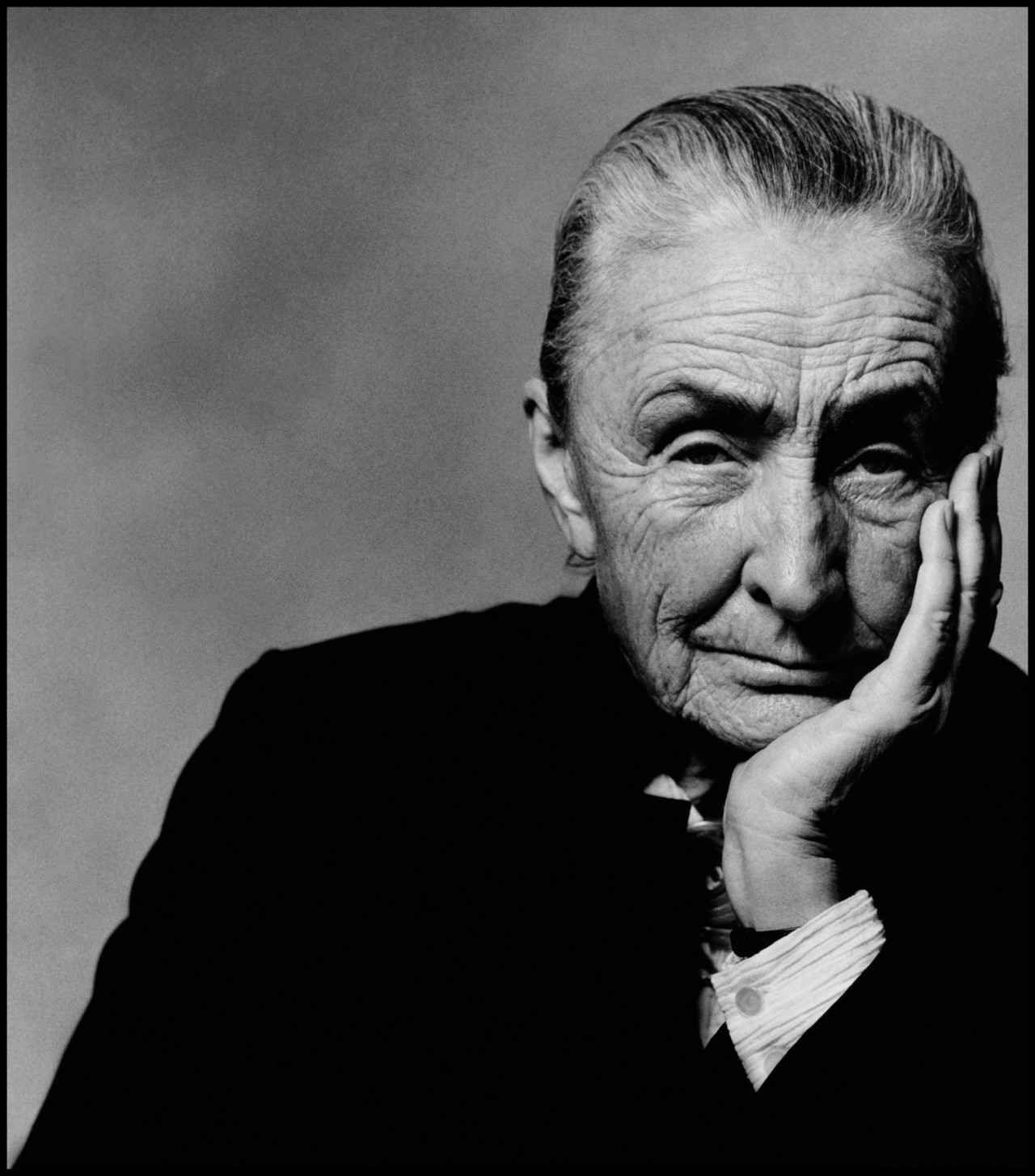

A much-photographed subject of the time, O’Keeffe was often portrayed by photographers as unsmiling and austere, probably due, in part, to the lifetime she spent fiercely rallying against those who tried to typecast her or box her into definitions she wasn’t comfortable with. But as the evening drew in and long shadows stretched across the walls behind O’Keeffe that day, Halsman’s pictures of this formidable woman – who regularly and vocally challenged her male contemporaries; who Joan Didion called ‘hard’ as the highest form of compliment; and who so caustically quipped, “If you don’t get it, that’s too bad” to the TIME Magazine interviewer who probed too literally about the meaning of her work – distil something of O’Keeffe’s wit and character with remarkable tenderness.

There is little else to record this first meeting between Halsman and O’Keeffe, other than the pictures themselves. There are no notes pertaining to it in Halsman’s archives, and only a handful of photographs of the other people who were there that day, including the photographer’s wife, Yvonne Halsman, and the wealthy patron Mabel Dodge Luhan, who, at the time, was a close friend of O’Keeffe.

After this, the pair didn’t have another portrait session until almost two decades later, in 1967. Those images were markedly different – close cropped, straight head shots, with harsh light and heavy shadow shot in a studio far from the ranch – and though a small softness radiates from O’Keeffe in those pictures too, with the same slight, knowing ghost of a smile on her lips, it’s the 1948 pictures that endure as a singularly important portrait of both artist and the place that continued to inspire her for the rest of her life.