Philippe Halsman and Salvador Dalí’s Enduring Partnership

The 37-year collaboration was fueled by a shared sense of humour and love for experimentation

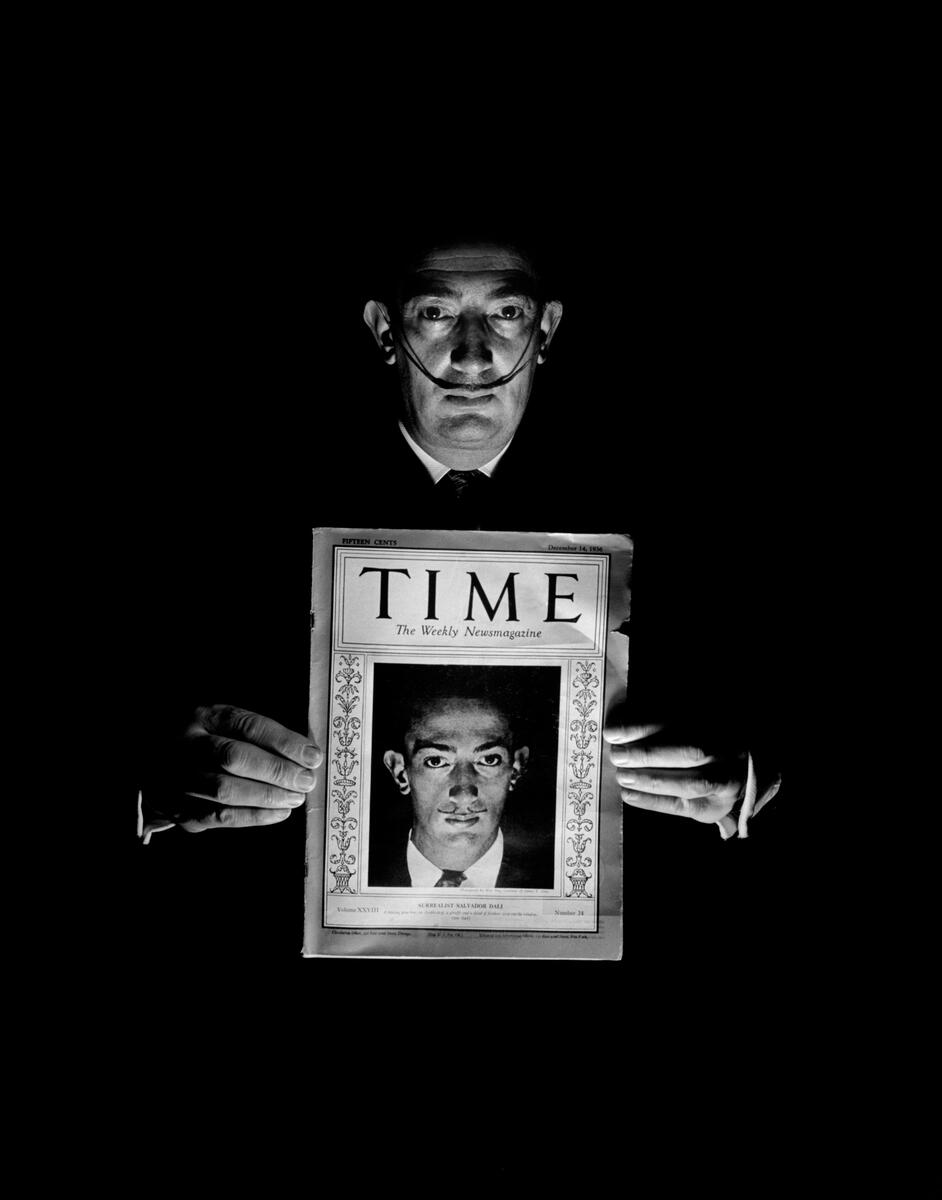

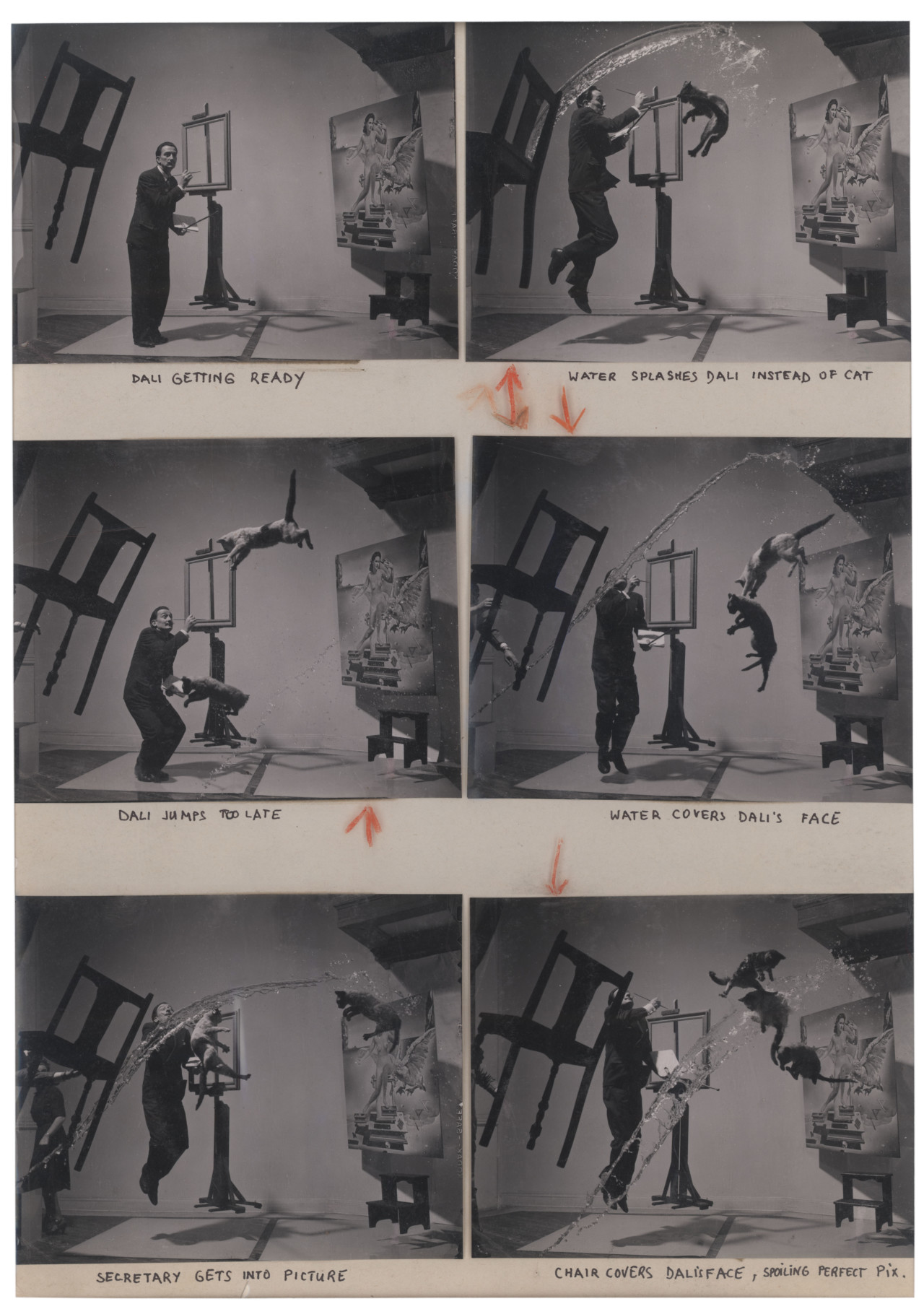

One of the longest and most celebrated creative partnerships in art history was the one between portrait photographer Philippe Halsman and Surrealist painter Salvador Dalí. Having first met in 1941, Halsman and Dalí embarked on a creative partnership that lasted for thirty-seven years and resulted in thousands of pictures, including 1948’s Dalí Atomicus. A few years after this technical feat, they produced Dalí’s Mustache (1954), a humorous book exploring myriad depictions of Dalí’s mustache.

“My father’s favorite picture of Dalí is not the one with the cats [Dalí Atomicus], which was voted one of the hundred most influential photographs of all time by Time magazine, but the one with the mustache – we call it ‘tilted portrait’,” says Irene Halsman, the photographer’s daughter. This photograph, which is one of the best-known portraits of the Spanish artist, sets the tone for a foray and odyssey into both the flexibility of Dalí’s trademark mustache, and Halsman’s skill as an experimental, radical photographer decades ahead of his time. “Before there was Photoshop, there was Philippe,” Irene says. For Halsman, no idea was too unconventional, even those suggested by the Surrealist.

"Before there was Photoshop, there was Philippe"

- Irene Halsman

“They were like two schoolboys collaborating, trying to shock the public”, continues Irene, who, as a young girl, often assisted her father on set. “They were gleeful: ‘Let’s do this!” Irene recalls meeting Dalí as a young girl. “It seems to me, every time I met Dalí, he was wearing the same blue pinstripe suit. He was so elegant and dapper. I thought he was very handsome. Dalí would come in the room saying, ‘Bonjour, Bonjour!’ And when he left, you know what he would say? ‘Bonjour, Bonjour!’ Whenever he would speak in a sentence, it was made up of three different languages. He would say, ‘Give me le book’ – it was always a third English, a third French and a third Spanish. He didn’t speak English very well.”

Humor fueled the longevity of Halsman’s friendship and collaborative spark with Dalí. Neither shied away from what others may have thought outrageous. In Halsman’s New York studio (“Dalí would call up my father every year when he came to New York”), the two men would ‘play’ – their term for putting their avant-garde ideas and scenarios into practice.

"Whenever he would speak in a sentence, it was made up of three different languages."

- Irene Halsman

One of these playful photographic sessions provided the genesis for the book. Admiring the length of Dalí’s mustache, which at the time reached the Surrealist’s eyebrows, Halsman declared that “Since nobody ever made a book on Van Gogh’s ear or Rembrandt’s nose, I’m going to make one on Dalí’s mustache!’”

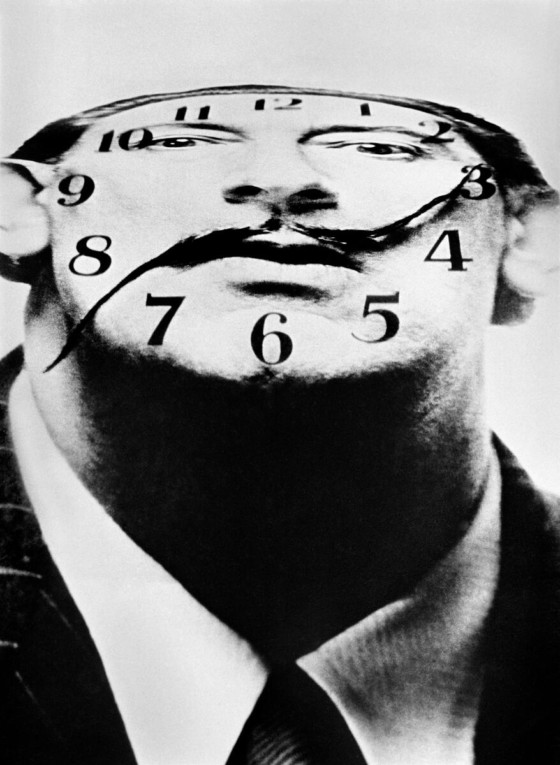

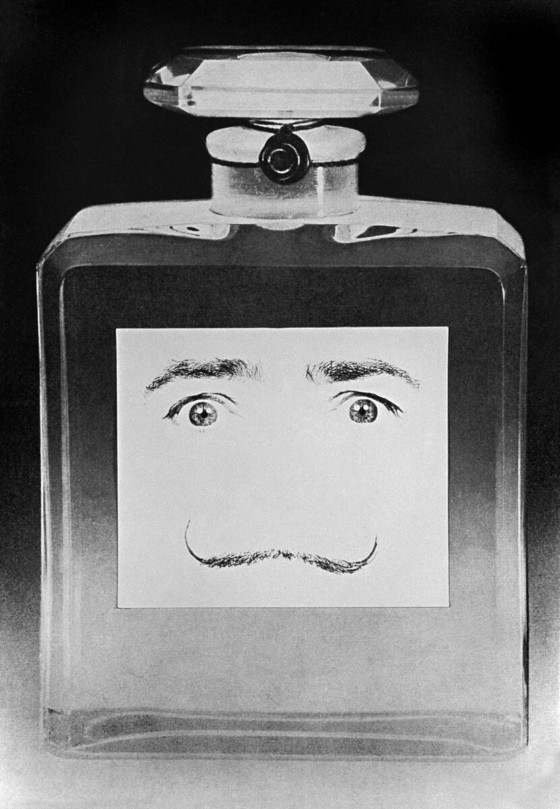

The book explores not only the versatility of Dalí’s trademark mustache but Halsman’s ability to think outside the parameters of traditional portraiture. After months of plotting their ideas, the two men came together to create the final images. “When Philippe had an idea, Dalí was always willing to oblige and be the protagonist. And when Dalí had a request like ‘Make me the Mona Lisa,’ Philippe would figure it out. He was also very inventive and imaginative.”

"When Philippe had an idea, Dalí was always willing to oblige and be the protagonist. "

- Irene Halsman

The book is small in size and length but vast in detail and scope, impressive from artistic and photographic perspectives. While the images are unique, the preparations to achieve them are equally fascinating. One photo of flies stuck on Dalí’s mustache, fixed with honey, was not completed in Dalí’s presence (the artist had returned to Europe) but with a replica of his mustache complete with a trusty application of Hungarian wax. The acute sharpness of Dali’s mustache on most of the images was thanks to the small jar of Hungarian wax, which was both the trick of Dalí’s mustache and the key to its malleability.

Dalí Atomicus took twenty-six takes and six hours, says Irene, and assisting Halsman’s quest for perfection and precision was his wife, Yvonne, an accomplished photographer in her own right. “You know, as a joke, my father used to say, ‘I married the competition.’”

Irene recalls frequently waking in the night and hearing her parents printing images, often until 3 a.m.. “My father didn’t give his pictures to anybody to print. He was a master printer.” Mrs Halsman spent hours putting honey onto the replica mustache before the honey dripped at precisely the right place. In another striking portrait, Halsman made a mobile by cutting up a photograph of Dalí’s face and suspending the eye, mustache and eyebrow and joining up the various pieces with wire.

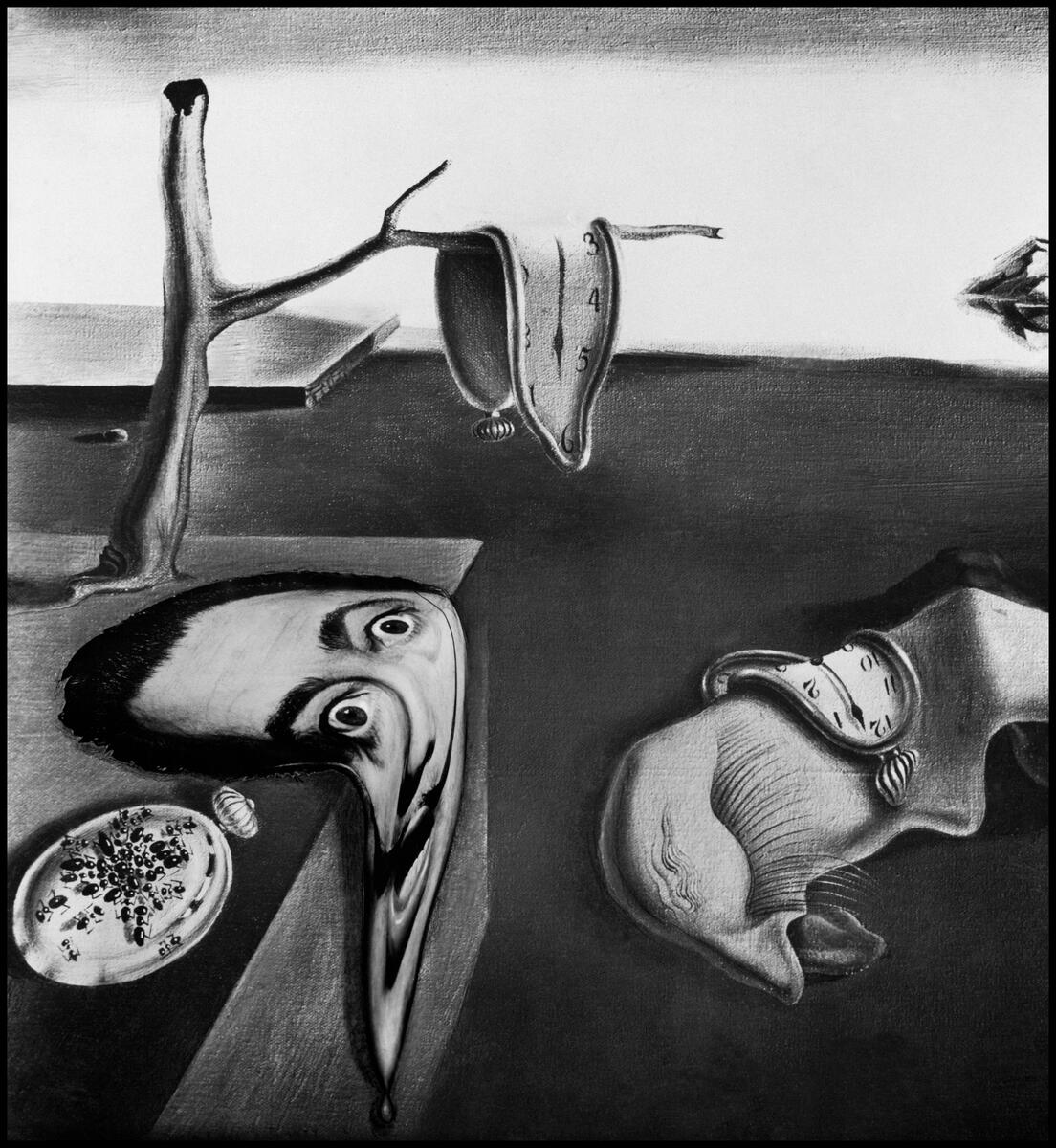

From making Dalí appear as the Mona Lisa to placing him inside the melting clocks of the The Persistence of Memory (1931), Halsman always found an answer to Dalí’s challenges, even when the idea revolved around an atomic bomb. “How are you going to show an explosion?” reflects Irene. “My father thought about it for a while and came up with a marvelous answer. He bought a rectangular fish tank about a foot and a half long and filled it. The night before the photo shoot, he tried his idea, using my sister Jane as a substitute. The following day, Dalí put his head in the fish tank, held a gulp of milk in his mouth, then spit it out, forming a perfect atomic cloud. Who else but my father would think of that innovative creative solution?”