Looking Elsewhere: On Philippe Halsman’s Portraits of Vladimir Nabokov

Juan Martinez, Assistant professor in English at Northwestern University and Nabokov scholar, on what happened when the Halsmans met the Nabokovs

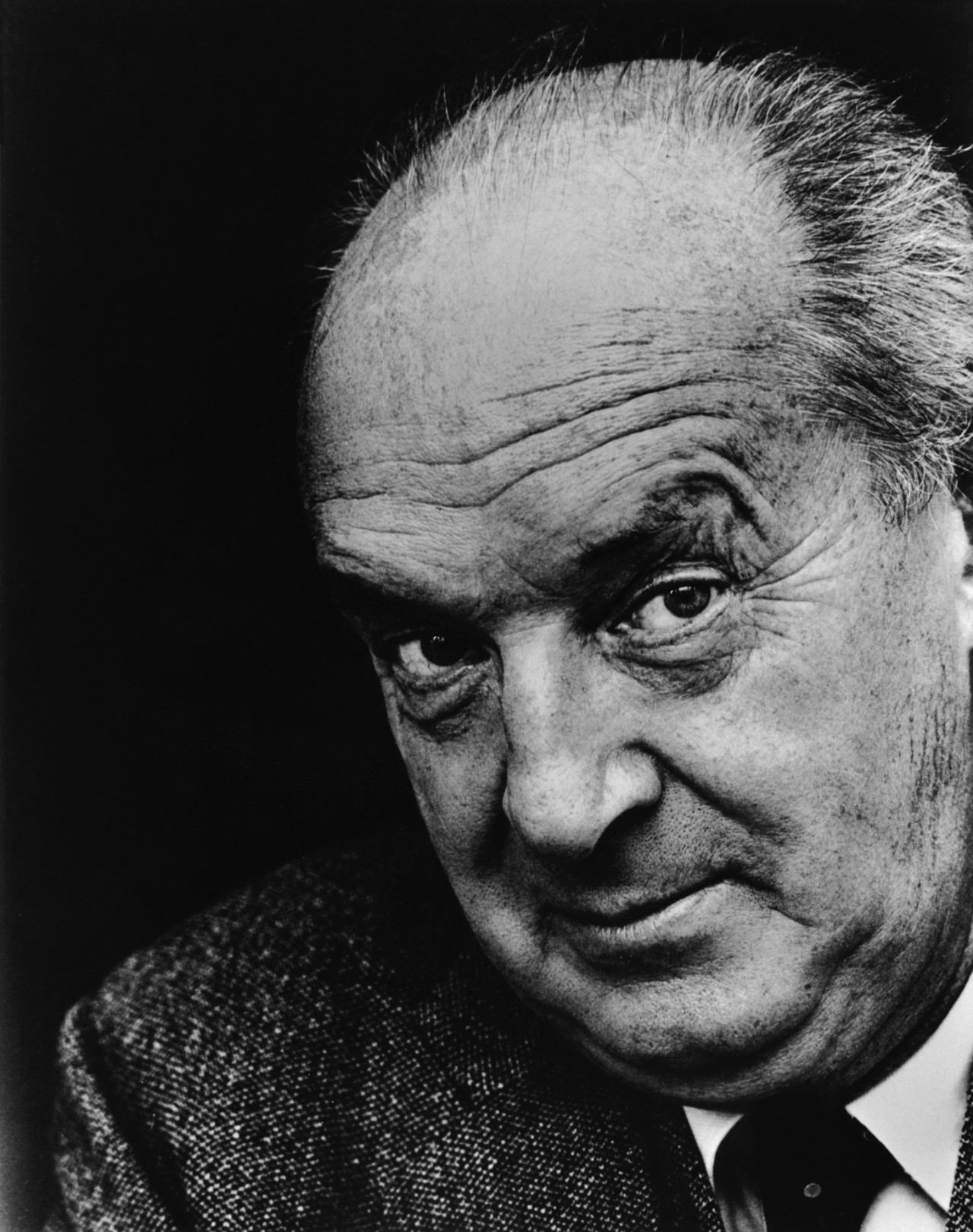

We rarely see Vladimir Nabokov staring at us directly in Philippe Halsman’s portraits, and when we do, it’s alarming. He looms over us, swinging his butterfly net our way. We’re prey, we’re a specimen, and he’s delighted by our imminent capture.

He seems frequently delighted by our being there, or that Halsman is, at least, in our stead. Brian Boyd, Nabokov’s biographer, puts it in much simpler, much more definitive terms: “Nabokov thought Halsman’s pictures the best ever taken of him.” Vladimir Nabokov loved the portraits so much that he asked that they be used in all subsequent book jackets. You’ll find Halsman’s portrait on the back of the 1968 edition of King, Queen, Knave, Nabokov’s face occupying the full frame, half of the features obscured in shadow, a half-smile still perfectly legible, eyes fully open but slightly averted from the camera.

"Nabokov thought Halsman’s pictures the best ever taken of him."

- Brian Boyd

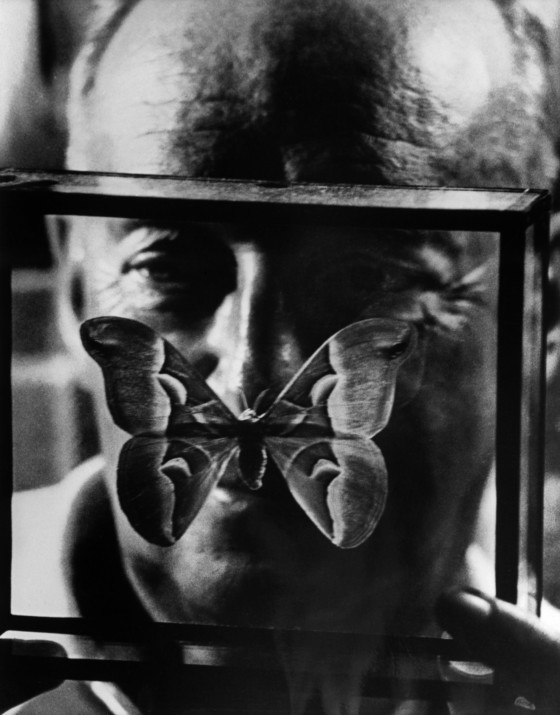

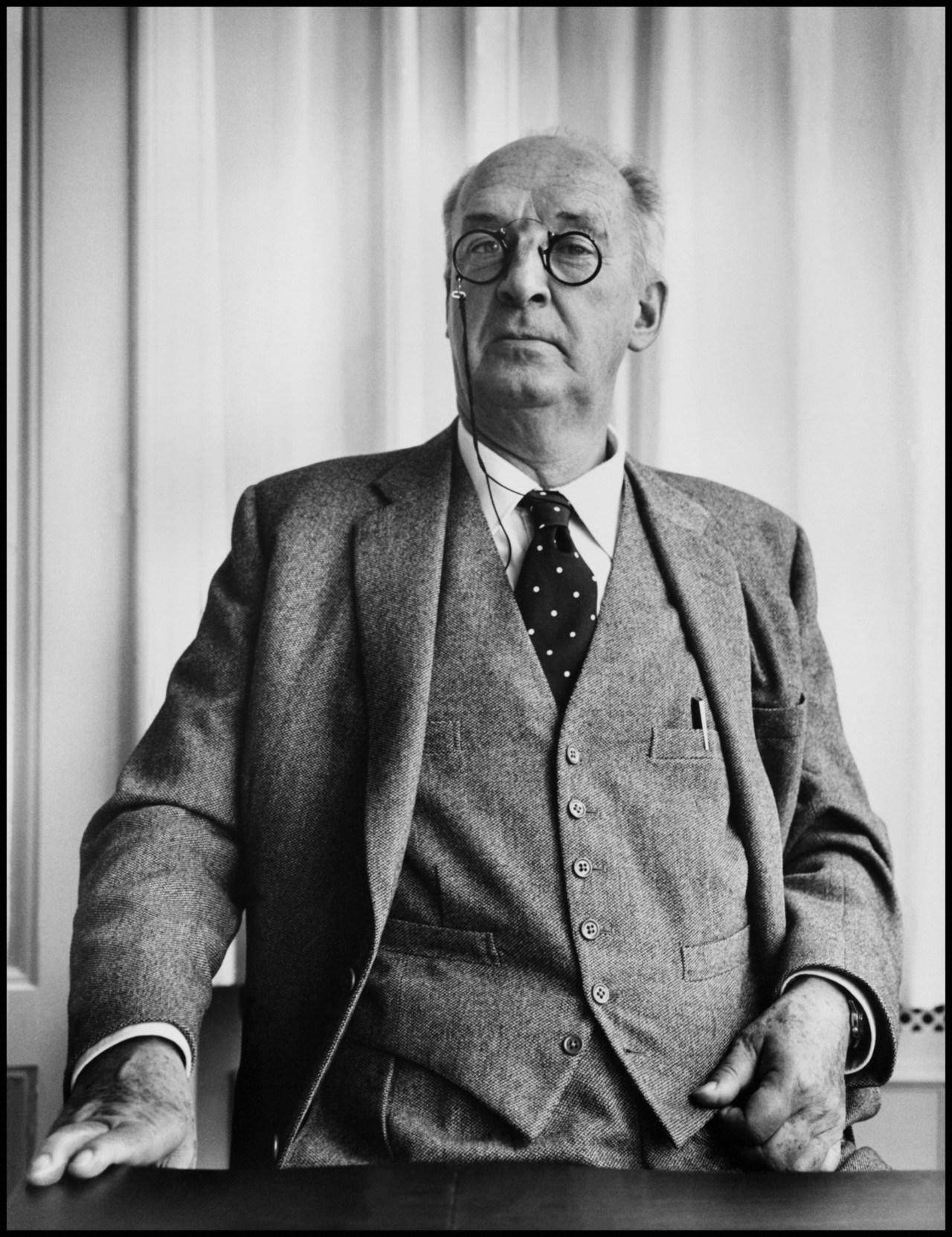

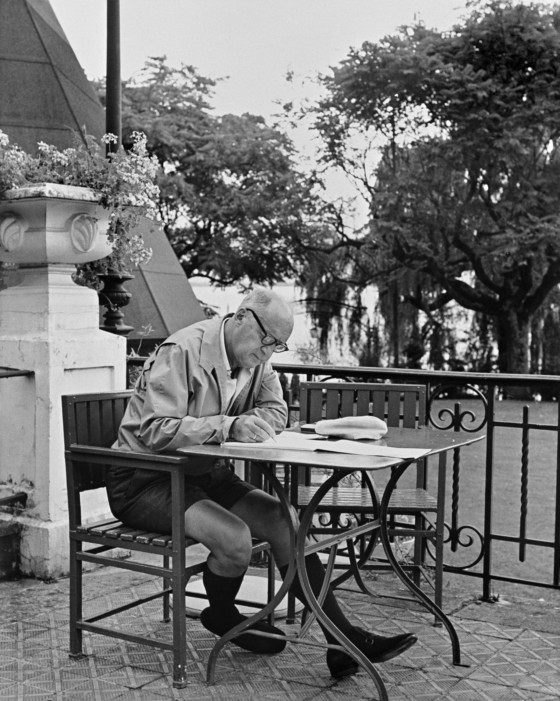

Some photos were taken over the course of a week in 1966 for a Herbert Gold Saturday Evening Post profile, and he’d return in 1968 for another session. The Golds and the Nabokovs became friends. The photos hit all the expected Nabokovian hallmarks: the lepidopterology, the professorial tweed, the inevitable pen-aloft-while-thinking-of-what-word-comes-next authorial stance, Nabokov with his beloved Webster’s dictionary, Nabokov the chess player.

I mention all of this to pose a problem of my own, which is that it’s tricky to separate what Nabokov chose to disclose about himself from a sense of who he actually was, the person behind the persona behind the author behind the novels.

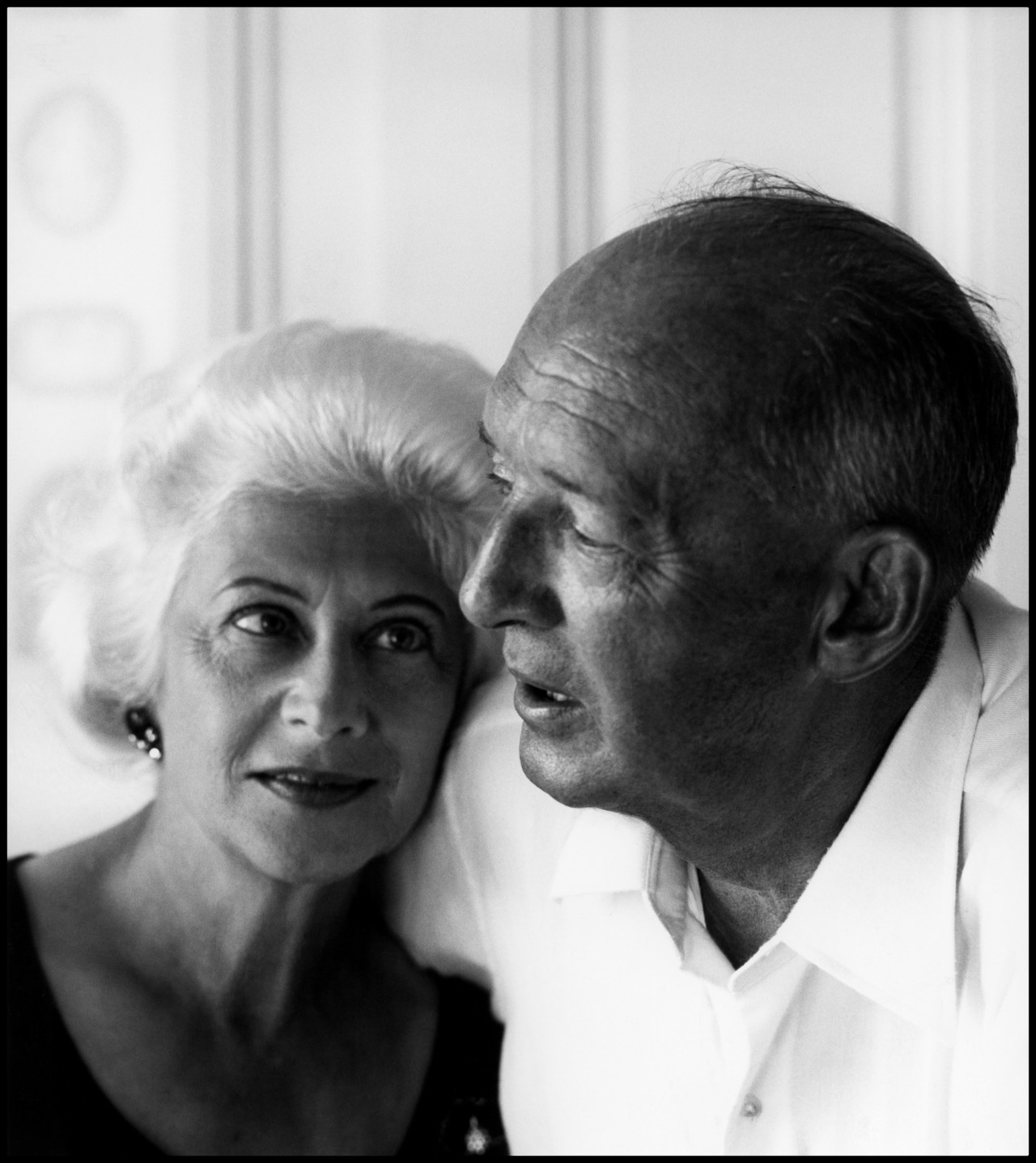

He kept himself guarded. Interviews were usually conducted in writing. Vera, Nabokov’s wife, worked hard to maintain his image (she often took care of the business correspondence, she typed his manuscripts, even negotiated a much more lucrative deal with McGraw-Hill once the Nabokovs decided to leave Putnam), and Gold himself noted this in 1966: “Occasionally she censors his conversation or interrupts an off-color story, but her steady regard expresses unshakable approval of her husband.”

Those are the words. In pictures, he played at spontaneity. Halsman praised Nabokov for “not giving a damn.” The photographer had just finished a dreary shoot of Lyndon Johnson, who was apparently vain, overly controlling, difficult and joyless in every way. Not Nabokov. It’s a peculiar historical moment, the one in which these two sets of photographs were taken. 1966 was tumultuous, but 1968 was altogether something else: the Paris riots, every other riot, the sense that the world was pulling apart. In that same issue of the Post where Nabokov gives us his half-smile, where Halsman gives us Nabokov’s favorite version of Nabokov, the cover belongs to Jackie Gleason, and the featured pieces are by Edward Kennedy on crime and Barry Goldwater, whose piece is titled “Don’t Believe What the Liberals Tell You,” on what he considered extreme media bias. It was all a funhouse, but maybe the wrong kind of funhouse. Nabokov, meanwhile, was living a dream of a life, his lifelong partner beside him.

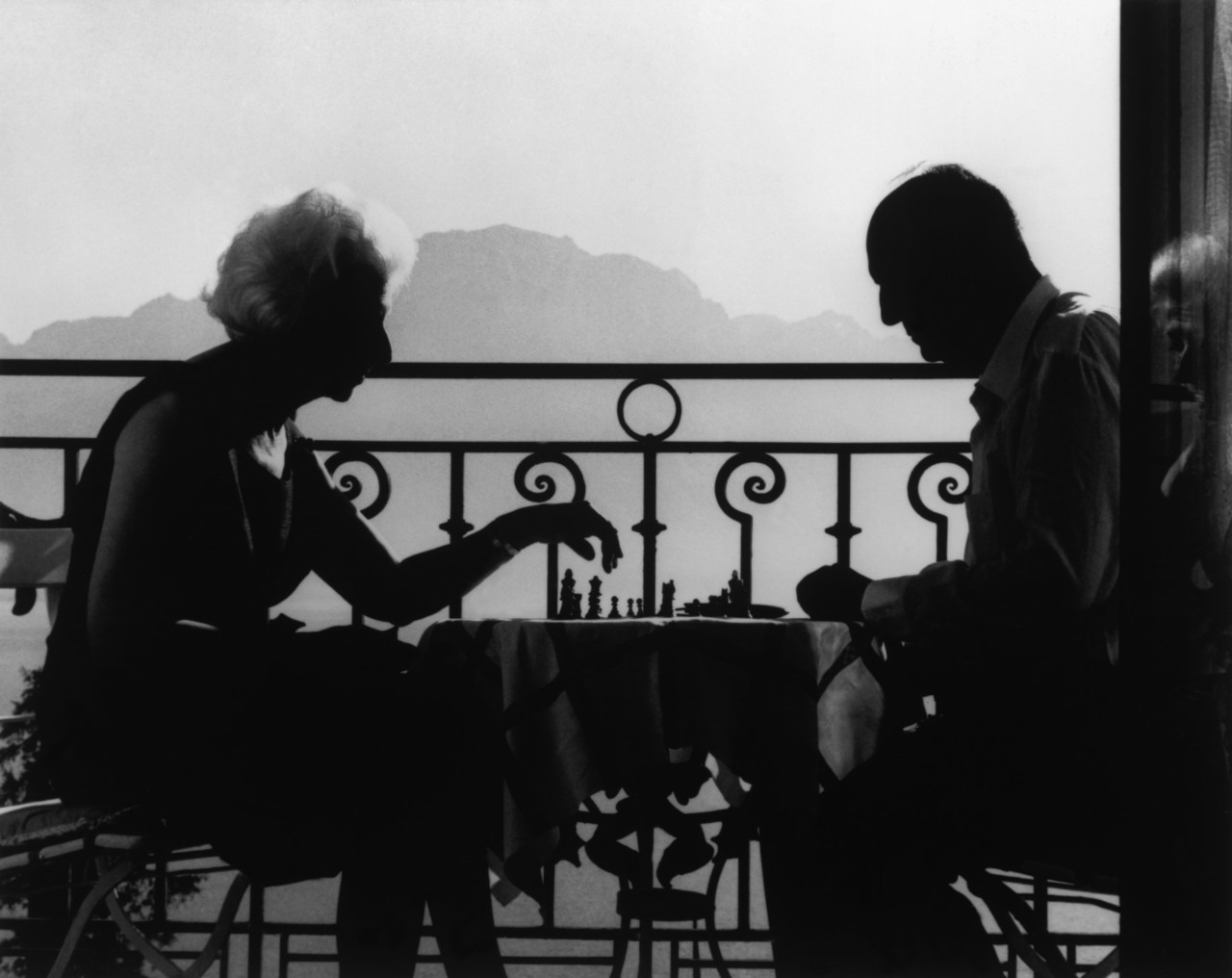

Stacy Schiff’s biography of Vera, notably, uses Halsman’s photos in the covers. The hardcover crops most of Vladimir out of the shot featured in the 1967 Post story – it’s mostly Vera, her white hair pouffed and swept back, head resting on her husband’s shoulder, her eyebrows and eyes jet-black. Again, a half-smile. Again, we’re there with Halsman for a moment just out of our reach. For the paperback, Schiff’s publishers decided to go with the Nabokovs in silhouette playing chess in a Montreux hotel balcony, Vera poised to make a move, eyes of both husband and wife on the board, Vera’s reflection on the glass of the balcony door.

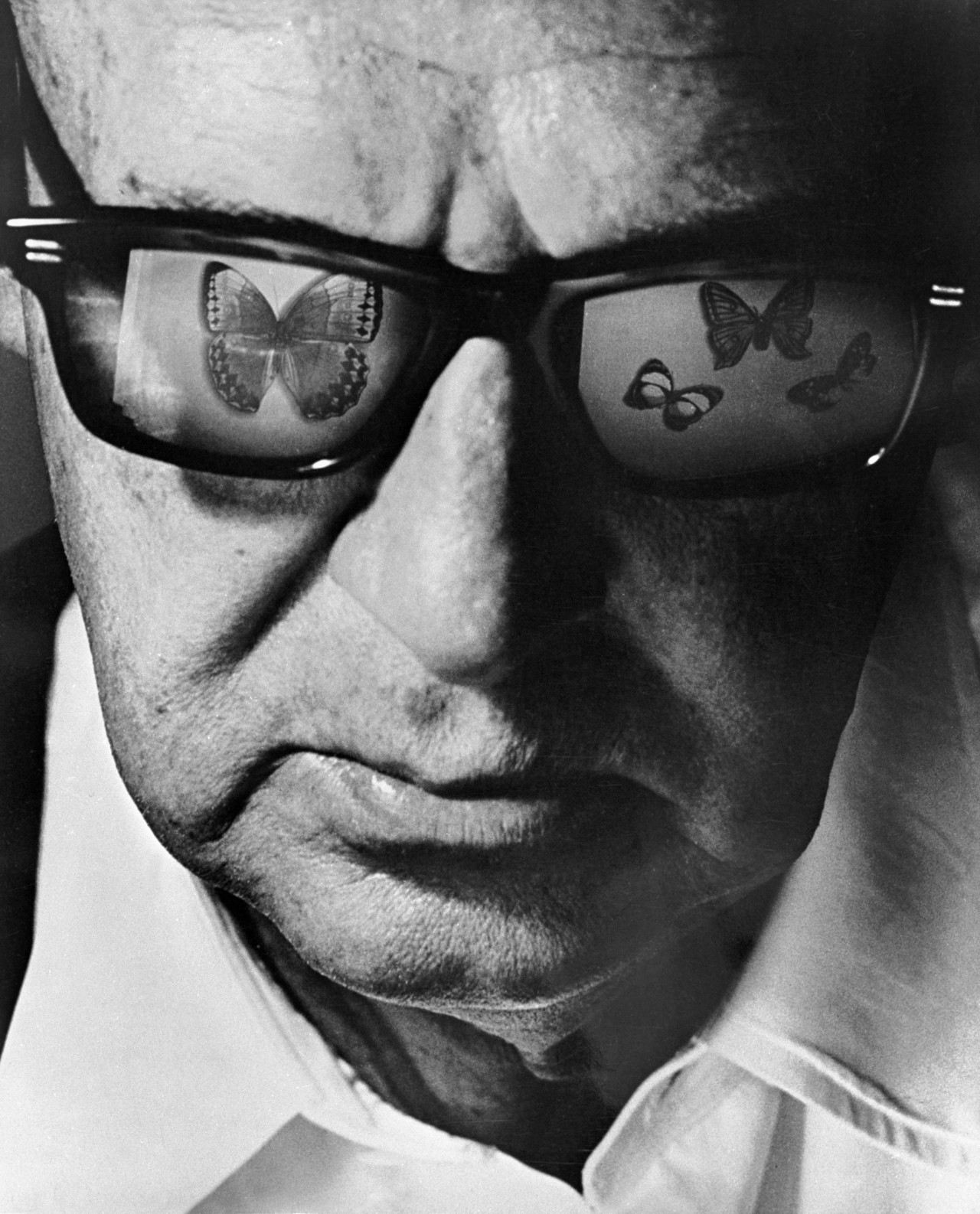

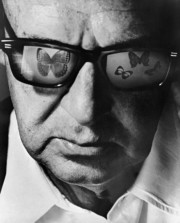

It is so immediately tempting to labor over these reflections. Halsman captures them so expertly: there, fading from the frame, is the bright blurred reflection of Vera’s white hair. And here are butterfly illustrations reflected in Vladimir’s glasses, a solitary specimen in one lens, a cluster of three in the other. So much of Nabokov’s work hinged on matters of perspective and perception and misperception – on what we were able to register and what just eluded our grasp, and so much of it played with identities that multiplied and refracted: think of Humbert Humbert, his name already a trick of the mirror, and his nemesis, Clare Quilty, in Lolita, or Hermann Karlovich convinced that he’s met his double in Despair (he hasn’t), or Charles Kinbote, posing as an academic but in reality the king of the long-lost kingdom of Zembla in Pale Fire. And Nabokov intrudes in his own work – he’s the annagrammatical Vivian Darkbloom in Lolita and Ada, but he’s himself, or a version of himself – an authorial presence at the end of “Cloud, Castle, Lake” and Pnin and even Look at the Harlequins! We are in the presence of someone who is a shadowy reflection of Nabokov himself.

"We are in the presence of someone who is a shadowy reflection of Nabokov himself."

- Juan Martinez

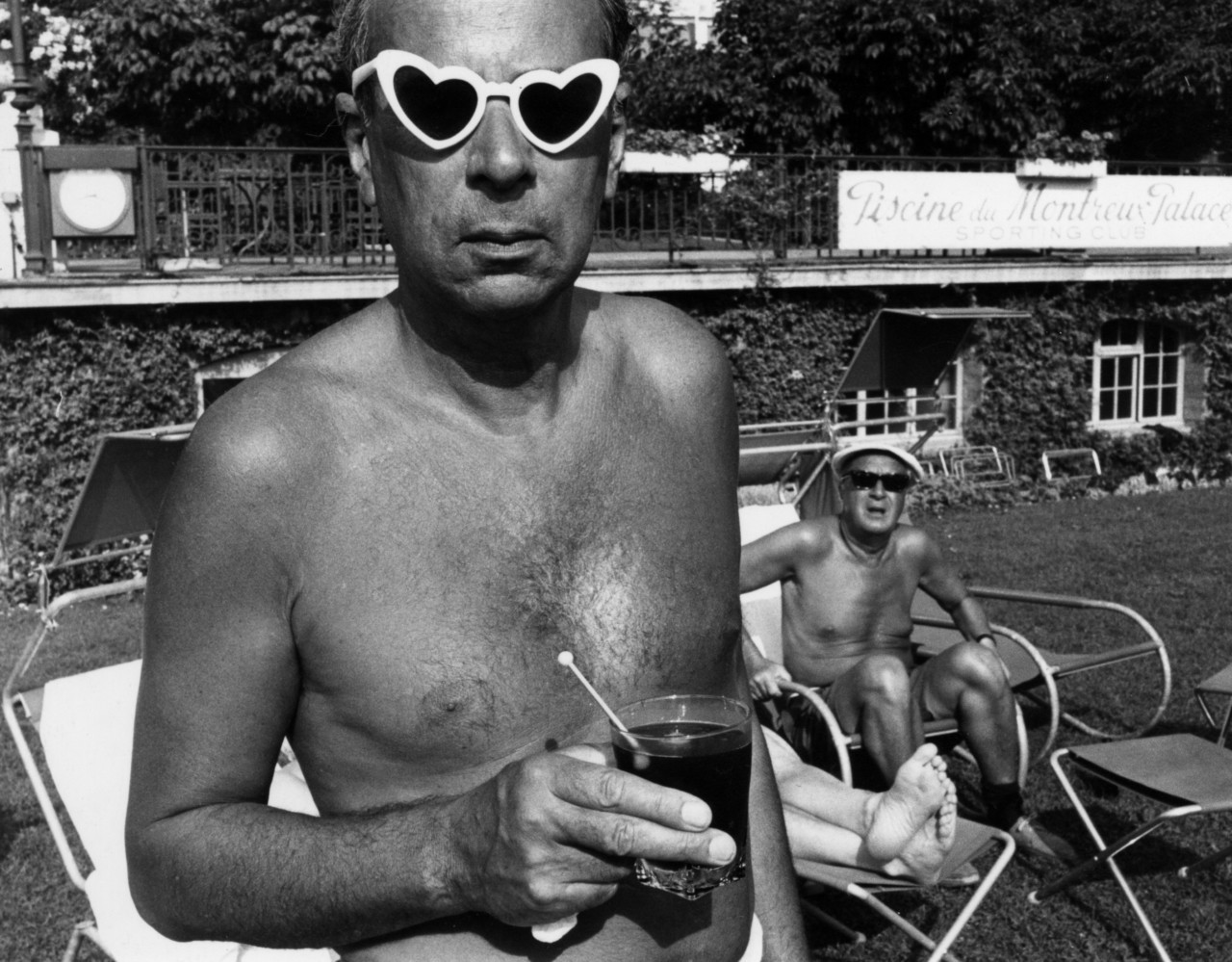

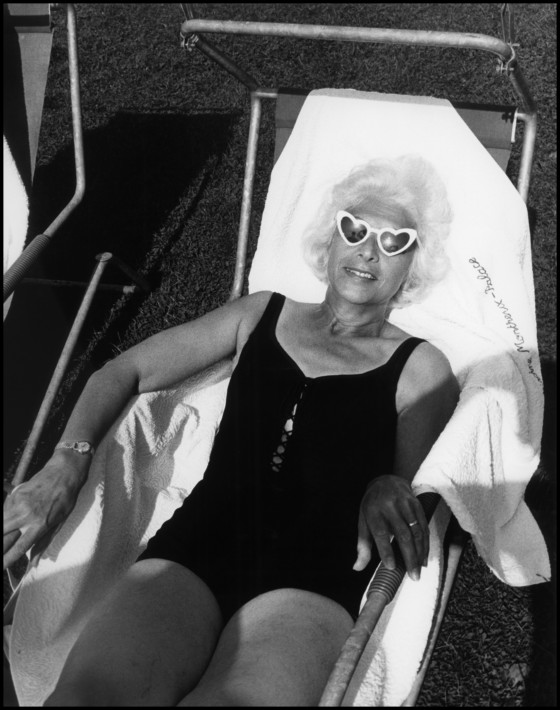

It is no surprise, perhaps, that he is at his most unguarded behind sunglasses, in the photo that Yvonne Halsman took of Philippe in Vera’s heart-shaped sunglasses, Nabokov himself in square frames, hands gripping his lounge chair. He’s speaking, or he’s about to speak, and he seems caught genuinely by surprise. Philippe’s own photo of the moment has Vera wearing the sunglasses, Vladimir behind her looking like he’s in the middle of a flamenco move. There’s joy in that photo, but it’s clearly also a bit of a posed moment. Right before, or right after (likely after), Philippe took the glasses from Vera, and posed for Yvonne, and Nabokov found himself captured in the background – he’s genuinely startled – hands gripping the resort chair, about to get up, about to say something. Let’s avoid the obvious lepidopteral metaphor. Mostly, let’s just enjoy that moment – a writer who delighted in surprising us, in pulling the rug from under us, captured in a moment that actually took him by surprise.

Juan Martinez’s book Best Worst American is published by Small Beer Press.