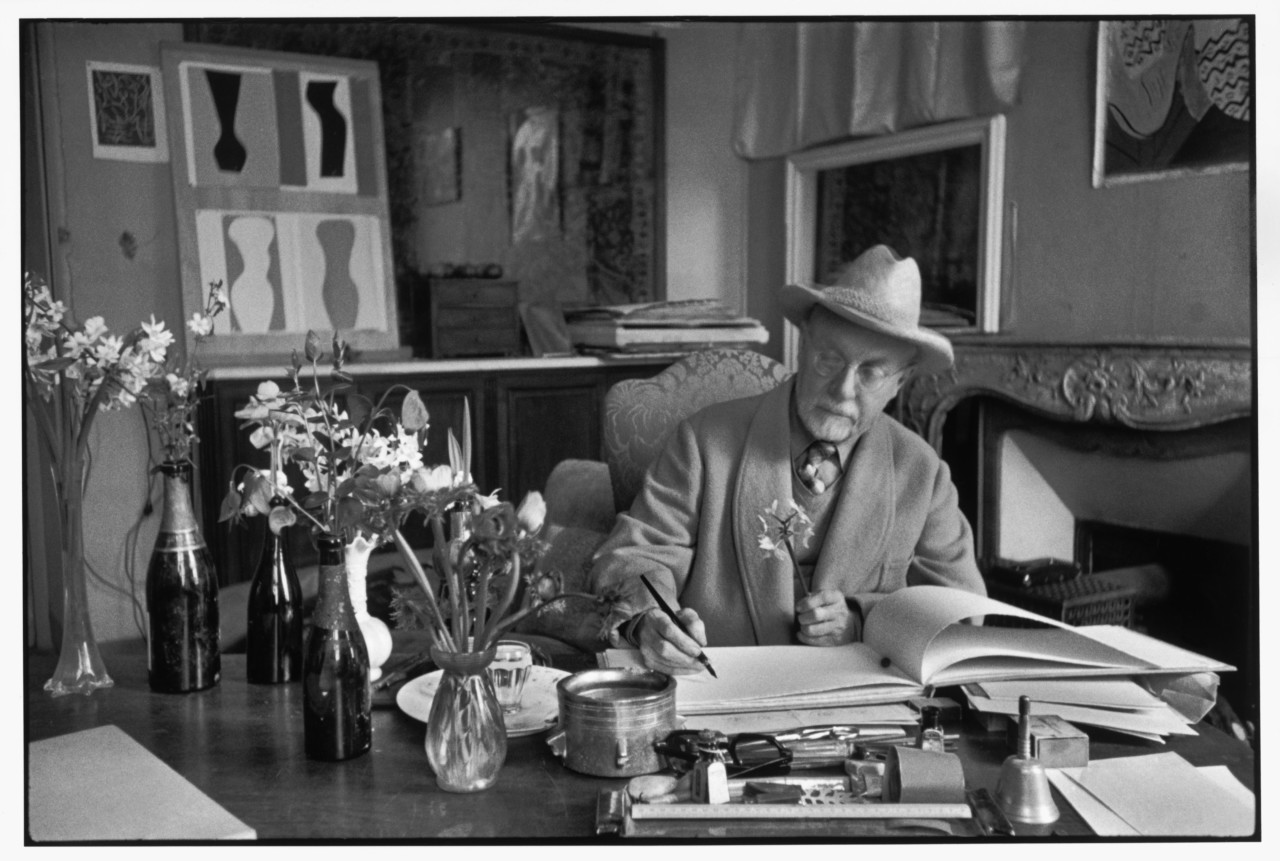

In the Studio: Matisse by Henri Cartier-Bresson

While on the run, having escaped a German labour camp, the Magnum co-founder observed the artist at work

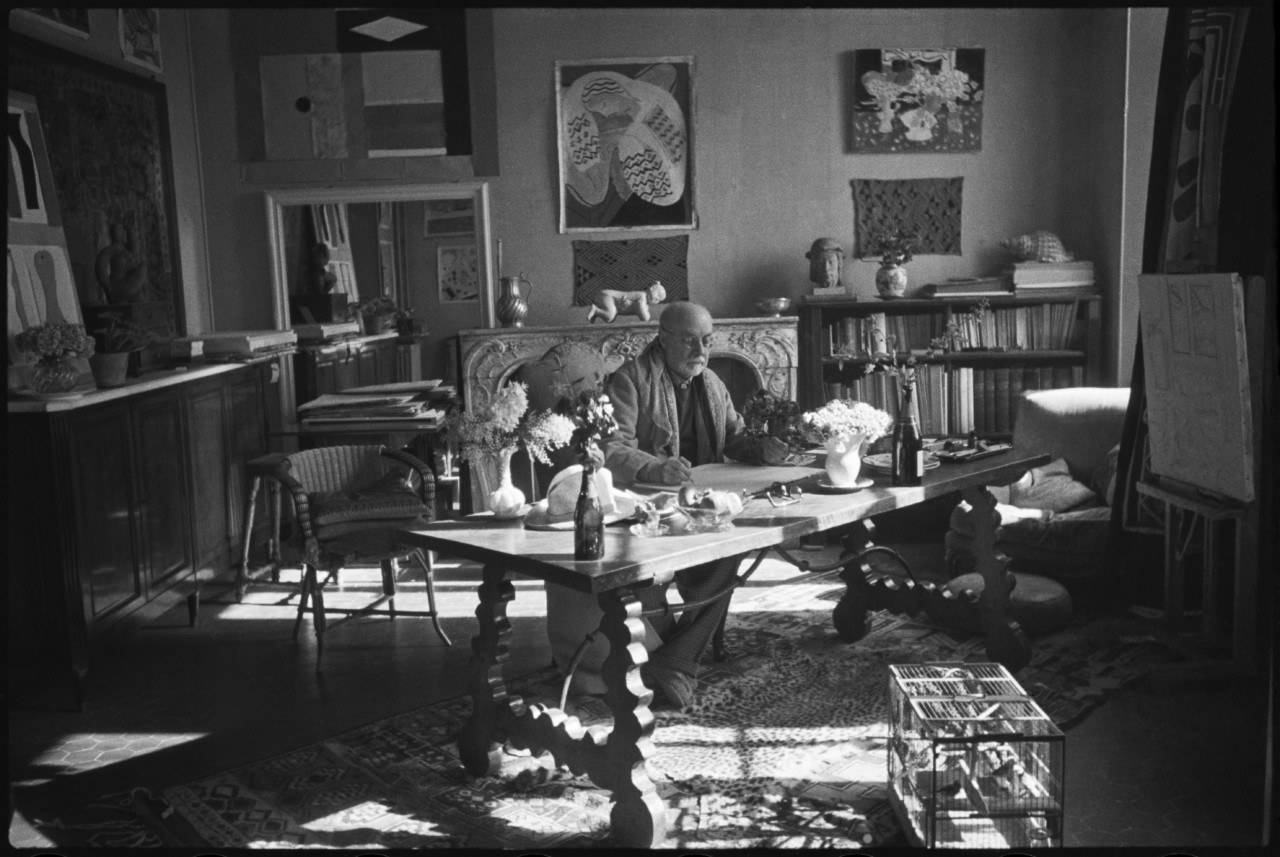

In the Studio is a series dedicated to the photographic documentation of artists within their workspaces. Over more than seven decades Magnum’s member photographers have captured images of the inner sanctums of many artists, often forging long-standing working or creative partnerships with them in the process. The images made in the studios of artists, in the company of their creatively imposing occupiers, reveal everything from insights on techniques and fabrication processes to illuminating clutter, reassuringly normal mess, and hints at the personal lives of individuals beyond their well known artistic output.

You can see other stories from the In the Studio series, here.

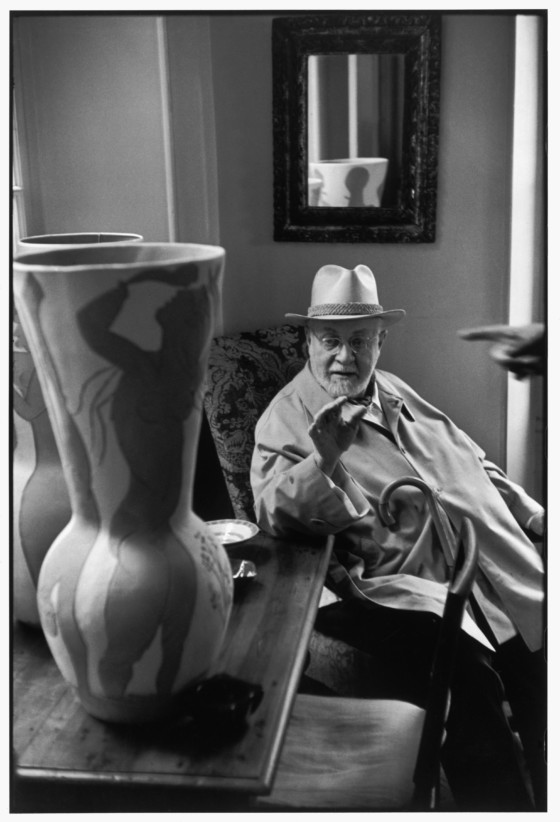

Henri Cartier-Bresson’s relationship with the artist Henri Matisse began in unusual circumstances. Taken as a prisoner of war by the Germans in 1940, Cartier-Bresson escaped from a work camp on his third attempt in 1943 and went on to join an underground organization assisting prisoners. During this time, while the 36-year-old was hiding out in France, he was asked by the publisher Pierre Braun to photograph writers and artists for a book project that never materialized. This assignment led Cartier-Bresson met some of the most prominent creative figures of the period. One of them was Matisse.

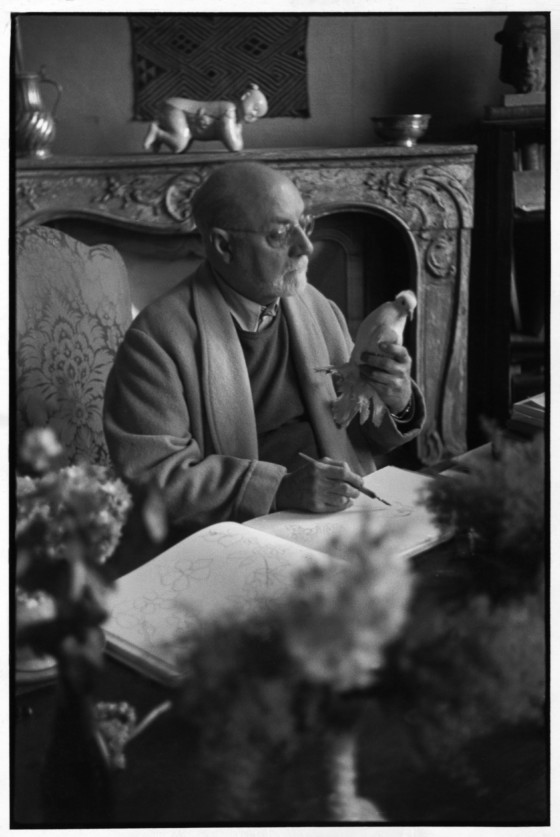

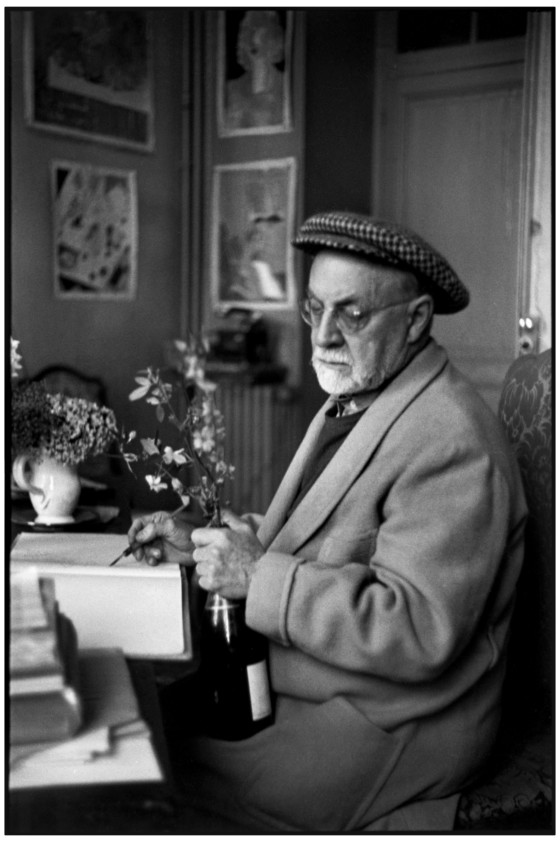

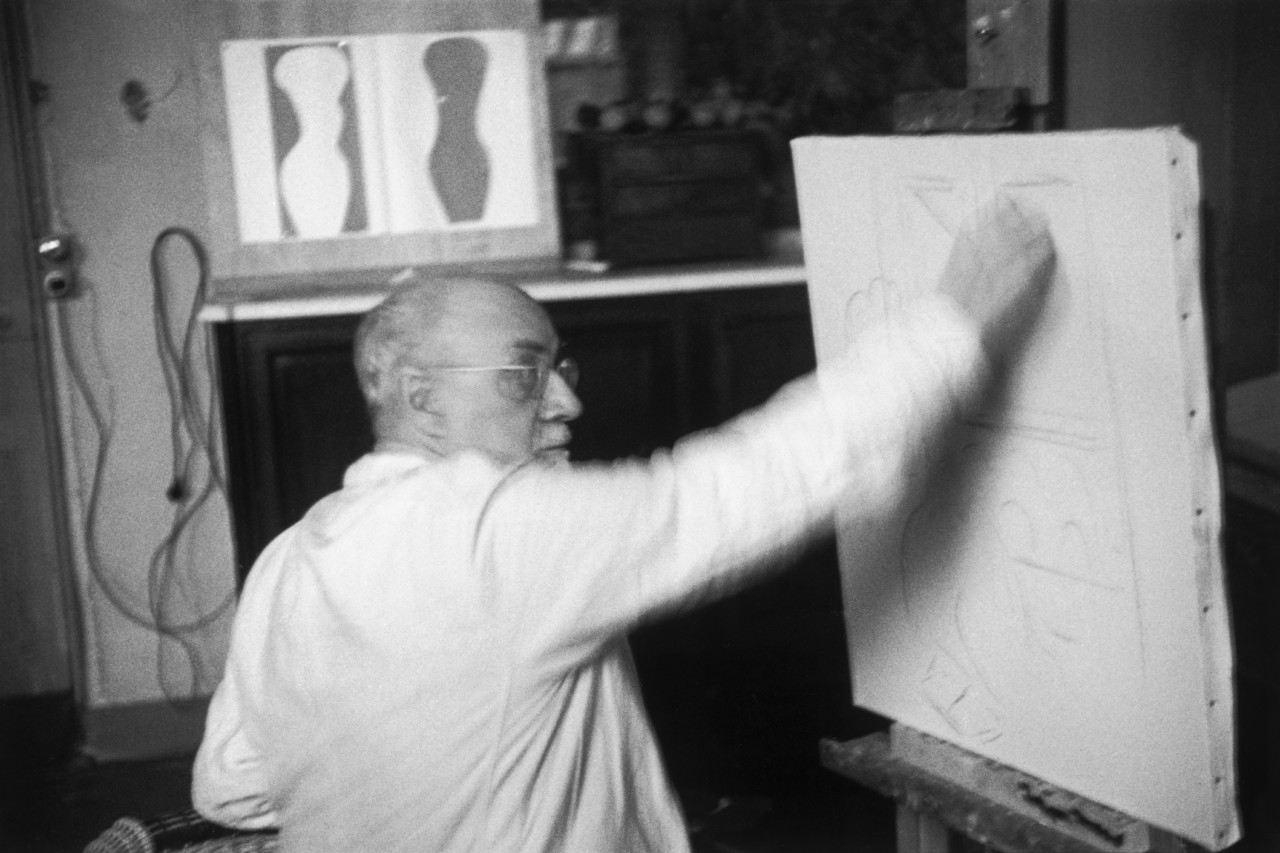

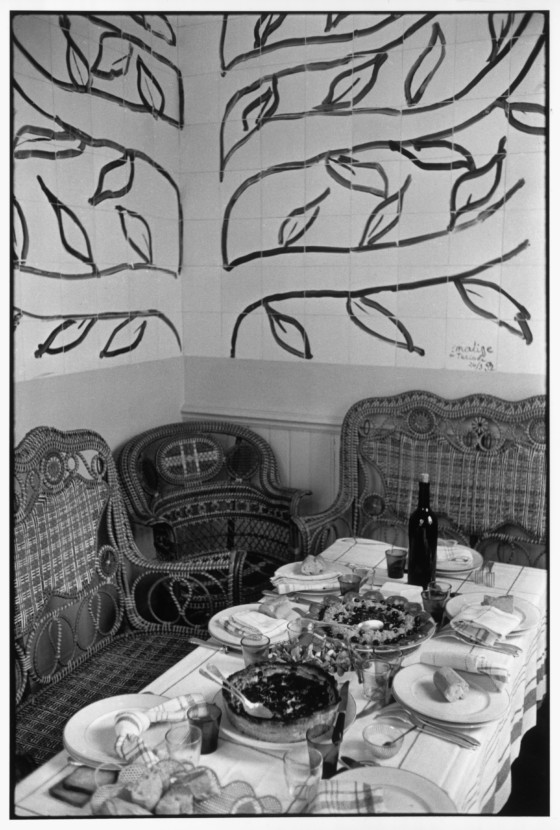

During 1944 Cartier-Bresson visited Matisse’s villa at Le Rêve, in the Alpes Maritimes region of the country, several times. The artist he met was by that time in his 60s and mostly chair and bed-bound, following a major surgery three years previously. Though his physical restriction was frustrating, for Cartier-Bresson, his art was always designed to soothe an aching body or mind – as Matisse explained: “What I dream of is an art of balance, of purity and serenity devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter – a soothing, calming influence on the mind, rather like a good armchair which provides relaxation from physical fatigue.”

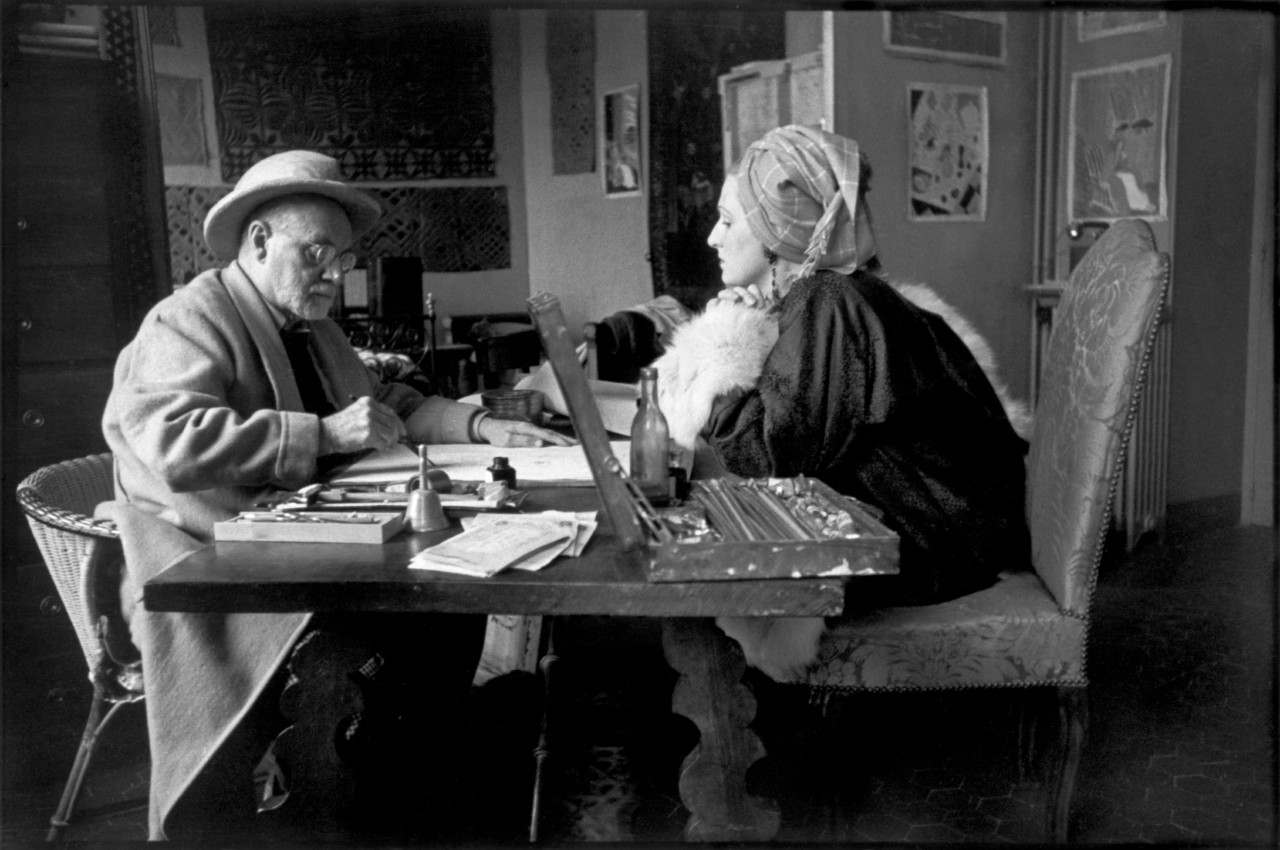

Indeed, despite his declining health, in these photographs we see Matisse still busy sketching and painting the white doves that flap about his sun-lit room, as well as with portraiture – working with his regular models Micaela Avogadro and Lydia Delectorskaya.

Delectorskaya was a young Russian émigré who had been a companion of Matisse’s wife, Amélie, until she discovered the pair’s affair in 1939 and subsequently ended their 41-year marriage. Following the exposing of the affair Delectorskaya attempted suicide, but survived a self-inflicted gunshot wound and returned to working with Matisse for the rest of his life.

For most of the war Matisse remained isolated in his villa in the Alpes-Maritimes, in the extreme south-west of France, nudging the Italian border. Occasionally the artist would spend time in his apartment in Nice, where Cartier-Bresson also photographed him. The photographer said of these visits to the villa: “When I used to go and see Matisse, I’d sit in a corner, I didn’t move, we didn’t talk. It was as if we didn’t exist.” This behavior was typical of the photographer, who had a talent for making people forget he was there.

Cartier-Bresson himself was an artist, having developed a strong fascination with painting from an early age. He had studied with the Cubist artist André Lhote in Chanteloup, France, as well as portraitist Jacques Émile Blanche, before turning to photojournalism in the 1930s. He once dared to show Matisse one of his gouaches and was amused by the sarcastic reply. Matisse apparently told him: “My box of matches doesn’t disturb me any more than what you’ve painted.”

Later, when he showed the mock-up of the Pierre Braun book to Matisse, the painter refused to be in it. “Too soon for the cult of personality,” he said. Despite this rebuff, in 1952, thanks to the editor Tériade, it was Matisse who created the original paper cut image that was used on the cover of Cartier-Bresson’s now essential book, The Decisive Moment.