In the Studio: Ousmane Sow by Martine Franck

Over two years from 1998 ro 1999, the photographer spent time in Sow's home and studio in Dakar, documenting his artistic process

In the Studio is a series dedicated to the photographic documentation of artists within their workspaces. Over more than seven decades Magnum’s member photographers have captured images of the inner sanctums of many artists, often forging long-standing working or creative partnerships with them in the process. The images made in the studios of artists, in the company of their creatively imposing occupiers, reveal everything from insights on techniques and fabrication processes to illuminating clutter, reassuringly normal mess, and hints at the personal lives of individuals beyond their well known artistic output.

You can see other stories from the In the Studio series, here.

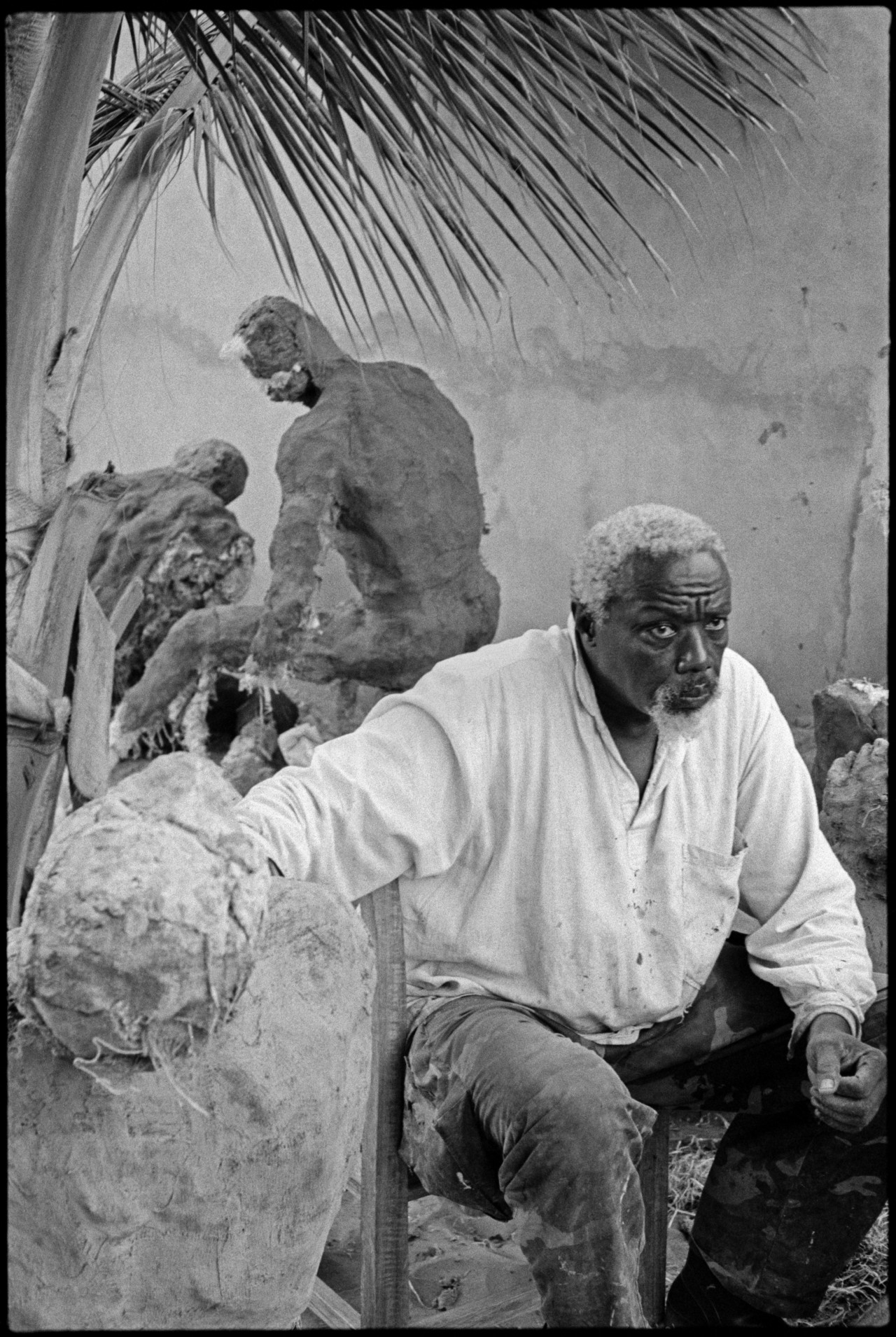

Ousmane Sow was a giant of the art world, in more ways than one. The Senegalese sculptor became renowned for his monumental, larger-than-life figures, intensely humanistic despite their looming frames. He is best known for his work on African nations, including the Nuba of southern Sudan (his breakthrough), the Masai of Kenya and Tanzania, the Zulus of South Africa, and the nomadic Fulani of West Africa.

French photographer Martine Franck, who joined Magnum in 1980, took portraits of many important cultural figures around the world, including the painter Marc Chagall, philosopher Michel Foucault and poet Seamus Heaney—and Ousmane Sow. Between 1998 and 1999, Franck spent time with the Sow in his studio and home in Dakar, documenting his unique process.

"If you wanted precision, you could copy the wooden horses from roundabouts"

- Ousmane Sow

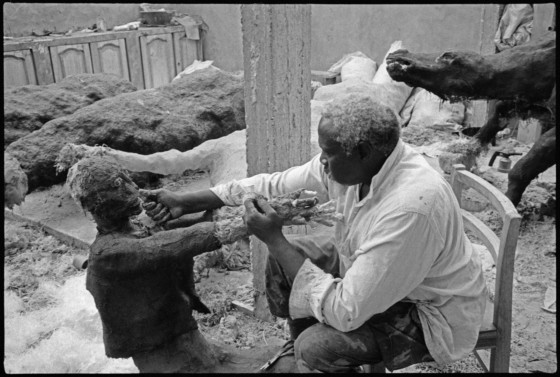

Rather than work with clay or wax, Sow used sacking and a paste made of a secret composition, which he built up around a metal wire frame. The results are rough, sometimes rugged, but smooth exactness was never Sow’s goal. “I find the scrubbed, shining finish of certain Greek sculptures rarely moves me,” he said. “If you wanted precision, you could copy the wooden horses from roundabouts. They are perfect but have no life, no depth.”

Sow showed an interest in sculpting from an early age but began in earnest in 1960, following his return to his native Senegal from France, where he had trained and worked as a physiotherapist. The job gave him financial stability as well as an intimate knowledge of the human anatomy. “I could be blindfolded and still make a human body from head to toe,” he once said. He was drawn to the spirit of those who resisted oppression, and in this way, he was a perfect subject for Franck; she too was interested in illuminating the stories of people who were persecuted and living on the peripheries of society.

"I find the scrubbed, shining finish of certain Greek sculptures rarely moves me"

- Ousmane Sow

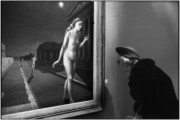

Some of the pieces seen in Franck’s pictures would later be shown at his 1999 exhibition at Pont des Arts, Paris, a walkway between the Louvre and the Académie Française. He presented 75 pieces for the show, drawing from his African series but also his series called The Victory of the Battle of Little BigHorn, which depicted the 1896 battle whereby a force of Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho Native American warriors defeated Lt Col George Custer’s 7th Cavalry regiment. The show cemented his reputation as an internationally respected artist, attracting more than 3 million visitors. Sow would go on to show in museums around the world and became the first black artist to be made a foreign associate member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts of the Institut de France.